Rome and Venice, Italy

by Anne Harrison

The heavy wooden door closed and I stood surrounded by silence. Flying anywhere from Australia takes a long time, and after a night and a day and a night I was exhausted. Tired and befuddled, I emerged into the chaos of Rome. I finally found a taxi, with a driver who careened down tiny streets where footpaths were more a suggestion than reality.

The heavy wooden door closed and I stood surrounded by silence. Flying anywhere from Australia takes a long time, and after a night and a day and a night I was exhausted. Tired and befuddled, I emerged into the chaos of Rome. I finally found a taxi, with a driver who careened down tiny streets where footpaths were more a suggestion than reality.

After he double-parked on the wrong side of the road, I alighted on the Via Sistine. The convent was just a few minutes from the top of the Spanish Steps. Once inside, the world became peaceful. Large wooden doors shut out the chaos of the street, and I stood in the quiet of a marble foyer. Convents and monasteries have offered hospitality for centuries, providing more economical accommodation than most hotels. Italy especially has a plethora of choices. The vast majority accept guests of both sexes, married or single, of any denomination – although some still pose a nightly curfew.

Rooms may be simple, but this does not imply austerity. Convents and monasteries are often to be found in Renaissance palazzos, Medieval walled towns or set amongst lavender fields and vineyards. Many hide artistic treasures; a painting by Rubens, or walls adorned by Fra Angelico. Each religious house has its own character, such as the monastery Convento Sant’Agostino in San Gimigiano which refused entry to HRH The Prince of Wales when he arrived after closing time. (Although probably apocryphal, the story alone makes the place worth a detour.)

Rooms may be simple, but this does not imply austerity. Convents and monasteries are often to be found in Renaissance palazzos, Medieval walled towns or set amongst lavender fields and vineyards. Many hide artistic treasures; a painting by Rubens, or walls adorned by Fra Angelico. Each religious house has its own character, such as the monastery Convento Sant’Agostino in San Gimigiano which refused entry to HRH The Prince of Wales when he arrived after closing time. (Although probably apocryphal, the story alone makes the place worth a detour.)

In Rome, I stayed at Le Soure di Lourdes. My room overlooked a cloister, and of a morning the singing of the nuns in their private chapel woke me in time for a simple breakfast of rolls, cold meats, and lots of hot coffee.

Rome boasts a convent or monastery in whatever quarter of the city you choose to stay. The rooms of Domus Carmelitana overlook the Castel Sant’ Angelo, while from those of Casa da Accoglienze Tabor you can see the Vatican. Near the Colsseum, the Cistercian Monastery of Santa Croce is in a 10th C building. Some of the balconies overlook ancient ruins and archaeological digs.

In Florence, the Casa Santo Nome di Jesu is in a 15th C palazzo. I reached my room via a marble staircase, complete with trompe l’oil ceiling of putti and plaster relief. The window overlooked a large garden, complete with kiwi fruit, persimmons, pomegranates, grape vines and wisterias, with trunks as thick as my body. The arbour was a perfect place to sit and pass the afternoon when exhausted by sightseeing.

In Florence, the Casa Santo Nome di Jesu is in a 15th C palazzo. I reached my room via a marble staircase, complete with trompe l’oil ceiling of putti and plaster relief. The window overlooked a large garden, complete with kiwi fruit, persimmons, pomegranates, grape vines and wisterias, with trunks as thick as my body. The arbour was a perfect place to sit and pass the afternoon when exhausted by sightseeing.

One evening, as I sipped prosecco and dined off a meal of delicacies from the markets, (plus some grapes purloined from the garden) I sat listening to a baroque choir (who were also guests) practicing for an upcoming performance.

Most convents provide breakfast – fresh rolls and strong coffee are a staple – and often dinner as well. In some, monks still make wine to recipes centuries-old. My first time in Venice, my choice lay at the end of a maze of cobble-stoned side streets and piazzas. The Instituto San Giuseppe stands beside a canal, with a door opening directly onto the water. As I crossed a small limestone bridge a gondola came to a boisterous stop to collect passengers.

Most convents provide breakfast – fresh rolls and strong coffee are a staple – and often dinner as well. In some, monks still make wine to recipes centuries-old. My first time in Venice, my choice lay at the end of a maze of cobble-stoned side streets and piazzas. The Instituto San Giuseppe stands beside a canal, with a door opening directly onto the water. As I crossed a small limestone bridge a gondola came to a boisterous stop to collect passengers.

The way to my room proved another maze of grand staircases and marble halls. Paintings covered the ceilings and walls – in a room large enough to host a masked ball, a fresco peeked out from under the scaffolding of restoration. Occasionally a nun in a black habit would wander by, smile and give a blessing, before continue on her way.

My room was simple and clean. The windows opened onto a terracotta skyline, with clothes strung on a line between two buildings. Across a flower-strewn courtyard a woman in black was busy in her kitchen, filling the air with delicious aromas. Every evening an extended family materialised for dinner. Geraniums hung everywhere in pots. In the distance a camponile tolled away the hours while towering (at a slight angle) over the other buildings,

My room was simple and clean. The windows opened onto a terracotta skyline, with clothes strung on a line between two buildings. Across a flower-strewn courtyard a woman in black was busy in her kitchen, filling the air with delicious aromas. Every evening an extended family materialised for dinner. Geraniums hung everywhere in pots. In the distance a camponile tolled away the hours while towering (at a slight angle) over the other buildings,

Everyone should fly into Venice – with a window seat – at least once in their life. Suddenly the history of Venice makes sense, from whenshelter was sought from the invading Goths amongst the swampy, malarial marshes, to her days of seafaring glory. Even from the heavens Venice is breathtakingly beautiful, especially when bathed by an autumn sun while storm clouds swell on the horizon.

The next essential is catching a boat from the airport to the city, either on the public vaporetto, or by a much faster private boat. Our vessel was all streamlined wood, the skipper as sleek and polished as his vessel. Despite a complete lack of Italian, as soon as my husband began admiring the boat (being a long-time sailor himself) the skipper happily displayed the boat’s paces. As the rain finally poured down and visibility vanished, he raced along the narrow channel to the city, overtaking every other boat in a shower of spray.

The next essential is catching a boat from the airport to the city, either on the public vaporetto, or by a much faster private boat. Our vessel was all streamlined wood, the skipper as sleek and polished as his vessel. Despite a complete lack of Italian, as soon as my husband began admiring the boat (being a long-time sailor himself) the skipper happily displayed the boat’s paces. As the rain finally poured down and visibility vanished, he raced along the narrow channel to the city, overtaking every other boat in a shower of spray.

Next came a gentle cruise through a network of tiny canals. Some were barely wide enough for the boat, the wash lapping against the buildings and doors in a moss-tipped waterline. Crumbling buildings complete with Juliette-balconies and geraniums stood tranquilly along the canal, as they have for centuries. Seagulls called overhead, bridges arched gracefully over the water, and the chaos of travel and Italian airports floated away. We even passed the gondolier repair shop on the Rio San Trovaso, one of the few remaining squeri in Venice.

The entrance to the convent Canossian Institute San Trovaso lies on a pretty canal, devoid of tourists. Being in the Dorsoduro area of Venice, the streets are far less crowded than the more popular areas, locals outnumber the tourists, and at night the area is quiet. An elderly nun opened the door, and we walked into tranquility. She led us through an inner courtyard, where some other guests sat sipping wine as their kids feasted on gelato.

The entrance to the convent Canossian Institute San Trovaso lies on a pretty canal, devoid of tourists. Being in the Dorsoduro area of Venice, the streets are far less crowded than the more popular areas, locals outnumber the tourists, and at night the area is quiet. An elderly nun opened the door, and we walked into tranquility. She led us through an inner courtyard, where some other guests sat sipping wine as their kids feasted on gelato.

Our room was clean, spacious and simple, with a balcony overlooking a courtyard of vines and roses. each morning I woke to the call of seagulls and the sound of church-bells. As is the way all over Italy, each church keeps its own, strict time, with the bells chiming a few minutes apart, never quite in unison.

Convents and monastery are not only in cities, but also in idyllic countryside settings. Stays are not restricted to Italy, and some are to be found in the most unexpected of places. An example is the 12th century monastery Kriva Palanka, hidden in the Osogovo Mountains of Macedonia [TOP PHOTO]. It is worth a visit for the medieval frescoes alone.

Convents and monastery are not only in cities, but also in idyllic countryside settings. Stays are not restricted to Italy, and some are to be found in the most unexpected of places. An example is the 12th century monastery Kriva Palanka, hidden in the Osogovo Mountains of Macedonia [TOP PHOTO]. It is worth a visit for the medieval frescoes alone.

One I dream of visiting is L’Hospice du Great St. Bernard in the Swiss Alps. Until recently, the Augustine monks bred and trained St Bernard dogs for mountain retrieval work; now they provide a home for the animals over the summer months.

A convent stay may not initially appeal to everyone, but it is something well worth experiencing, not simply as a cheaper substitute for a hotel, but as a travel adventure in its own right. Seen as such, staying in one can only add to a holiday.

8-Day Best of Italy Tour from Rome Including Tuscany, Venice and Milan

If You Go:

Many convents and monastery now have their own website complete with email and online booking system. The websites below can help you choose:

♦ www.monasterystays.com – An extensive Italian listing

♦ http://www.santasusanna.org/index.php/resources/convent-accomodations – Concentrating mainly on Rome, but with some other Italian cities as well

♦ www.goodnightandgodbless.com – Although the book is more extensive, the website has world-wide listings

About the author:

Anne Harrison lives with her husband, two children and numerous pets on the Central Coast, NSW Australia. Her jobs include wife, mother, doctor, farmer and local witch doctor – covering anything from delivering alpacas to treating kids who have fallen head first into the washing machine. Her fiction has been published in Australian literary magazines, and has been placed in regional literary competitions. Her non-fiction has been published in medical and travel journals. Her ambition is to be 80 and happy. Her writings are at anneharrison.com.au and hubpages.com/@anneharrison

Photo credits:

Osogovo Monastery, Macedonia by MacedonianBoy / CC BY-SA

All other photos are by Anne Harrison:

A quiet alley near our convent

Rome’s Spanish Steps

Casa Santo Nome di Jesu, Florence

Entrance to Instituto San Giuseppe, Venice

A room with a view, Venice

The Squero San Travaso

The wonder of Venice

A gondola in Florence, naturally

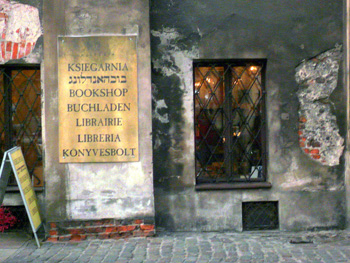

In March 1941, the Germans forced all Krakow Jews to resettle in the newly created ghetto of Kazimierz. The Nazis liquidated it only two years later on March 13, 1943. Most of the 17,000 inhabitants perished in the Nazi concentration camps. Today Krakow has only about 200 Jewish residents.

In March 1941, the Germans forced all Krakow Jews to resettle in the newly created ghetto of Kazimierz. The Nazis liquidated it only two years later on March 13, 1943. Most of the 17,000 inhabitants perished in the Nazi concentration camps. Today Krakow has only about 200 Jewish residents. Kazimirez is not beautiful; many of its buildings are run down. A few night clubs have emerged around the Square. We enjoyed just sitting and people watching… modern day residents and a few Jews dressed in shawls and yarmulkes. And, of course, the foreign tourists.

Kazimirez is not beautiful; many of its buildings are run down. A few night clubs have emerged around the Square. We enjoyed just sitting and people watching… modern day residents and a few Jews dressed in shawls and yarmulkes. And, of course, the foreign tourists.

The next thing on our list, however, was to sample some of the local food. There was no shortage of Jewish themed restaurants and shops.

The next thing on our list, however, was to sample some of the local food. There was no shortage of Jewish themed restaurants and shops. Another interesting feature are the walls in the prayer hall. Prayers have been painted on the walls for worshipers who couldn’t afford prayer books. Most readings have even been translated into English. A plaque outside states the synagogue was constructed in 1638, so there is some serious history attached to this place of worship.

Another interesting feature are the walls in the prayer hall. Prayers have been painted on the walls for worshipers who couldn’t afford prayer books. Most readings have even been translated into English. A plaque outside states the synagogue was constructed in 1638, so there is some serious history attached to this place of worship. In addition to the Jewish element, Christianity also had a role in Kazimirez. The Church of Corpus Christi has an awesome historical interior. There are stalls going back to 1629, the altarpiece of 1634, and the ornate mid-18th-century pulpit.

In addition to the Jewish element, Christianity also had a role in Kazimirez. The Church of Corpus Christi has an awesome historical interior. There are stalls going back to 1629, the altarpiece of 1634, and the ornate mid-18th-century pulpit.

Those simple early ninots have evolved into magnificent wax and polystrene figurines that require such precise skills that the artists who create them now have their own guild, The Guild of Falleros Artists; at least two schools who specialize in training them; two museums dedicated to their work and a part of Valencia known as Cuidad del Artisto Fallera (the City of Falleros Artists) where many of them have full-time workshops.

Those simple early ninots have evolved into magnificent wax and polystrene figurines that require such precise skills that the artists who create them now have their own guild, The Guild of Falleros Artists; at least two schools who specialize in training them; two museums dedicated to their work and a part of Valencia known as Cuidad del Artisto Fallera (the City of Falleros Artists) where many of them have full-time workshops.

The scale model and the massive pieces of the scene in the workshop did not do justice to the full scale of the monument as it was being constructed. Because of its sheer size, much of the actual carpentry happened in the plaza where the public could watch its daily progress. The monument, called Fallas of the World, consisted of a tall wooden human figure surrounded by world “monuments” that had been part of previous years’ fallas structures – the EIffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, the Concorde jet, the statues of David and Moses.

The scale model and the massive pieces of the scene in the workshop did not do justice to the full scale of the monument as it was being constructed. Because of its sheer size, much of the actual carpentry happened in the plaza where the public could watch its daily progress. The monument, called Fallas of the World, consisted of a tall wooden human figure surrounded by world “monuments” that had been part of previous years’ fallas structures – the EIffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, the Concorde jet, the statues of David and Moses.

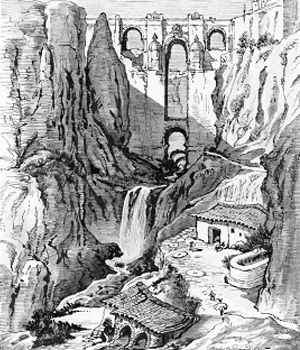

The sun is just setting behind the Serranía de Ronda (Ronda Mountain Range) and an hour and a half later, we arrive, relieved and unscathed.

The sun is just setting behind the Serranía de Ronda (Ronda Mountain Range) and an hour and a half later, we arrive, relieved and unscathed. Ronda is one of the oldest cities in Spain first settled by the Celts around the 10th century BCE as Arunda. The town continued to thrive under the Romans as did the nearby settlement of Acinipo originally founded by the Phoenicians. Today, ruins of a vast Roman theatre and thermal baths dated to the 1st century can be visited about 12 miles northwest from Ronda in the ancient city of Acinipo or, as it is locally known, Ronda La Vieja (Old Ronda.)

Ronda is one of the oldest cities in Spain first settled by the Celts around the 10th century BCE as Arunda. The town continued to thrive under the Romans as did the nearby settlement of Acinipo originally founded by the Phoenicians. Today, ruins of a vast Roman theatre and thermal baths dated to the 1st century can be visited about 12 miles northwest from Ronda in the ancient city of Acinipo or, as it is locally known, Ronda La Vieja (Old Ronda.)

Ronda is the birthplace of the highly gifted 9th century Muslim Andalusí physician, mathematician, and engineer known as Abbas ibn Firnas. Of Berber descent, Firnas was also an illustrious inventor creating such ingenious devices as a water clock, a mechanized planetarium, an armillary sphere, and even a flying machine (for this reason, he is known as the “father of aviation.”) Firnas was also skilled in astronomy, music, and poetry as well as being responsible for introducing glass-making techniques to al-Andalus (Andalusia during Muslim Spain.) Today, he has an airport in northern Baghdad and a lunar crater named in his honour as well as a bridge in Córdoba where he died in 887.

Ronda is the birthplace of the highly gifted 9th century Muslim Andalusí physician, mathematician, and engineer known as Abbas ibn Firnas. Of Berber descent, Firnas was also an illustrious inventor creating such ingenious devices as a water clock, a mechanized planetarium, an armillary sphere, and even a flying machine (for this reason, he is known as the “father of aviation.”) Firnas was also skilled in astronomy, music, and poetry as well as being responsible for introducing glass-making techniques to al-Andalus (Andalusia during Muslim Spain.) Today, he has an airport in northern Baghdad and a lunar crater named in his honour as well as a bridge in Córdoba where he died in 887. The town of Ronda is connected by three bridges that cross the deep canyon adding to the city’s remarkable features. The Roman Bridge is the oldest dating to the 11th century. Although it is Arabic in origin, it was likely constructed over an older Roman bridge. After the Christian conquest it was renamed Puente de San Miguel (St. Michaels Bridge.) Not far away is the early 17th century Puente Viejo (Old Bridge) and smallest of the three. As it was built over the ruins of an old Arab bridge, it is also known as Puente Árabe.

The town of Ronda is connected by three bridges that cross the deep canyon adding to the city’s remarkable features. The Roman Bridge is the oldest dating to the 11th century. Although it is Arabic in origin, it was likely constructed over an older Roman bridge. After the Christian conquest it was renamed Puente de San Miguel (St. Michaels Bridge.) Not far away is the early 17th century Puente Viejo (Old Bridge) and smallest of the three. As it was built over the ruins of an old Arab bridge, it is also known as Puente Árabe. After crossing this bridge, I wander the charming old Moorish quarter with its winding pedestrian streets, white-washed houses, and historic squares. Locally known as La Ciudad (The City), the old quarter is situated on the south side of the gorge as opposed to the newer city on the north. Not for from Puente Nuevo in the historic quarter is an interesting gate known as Arco de Felipe V (Arch of Philip V.) This emblematic arch or gate, crowned by three pinnacles, was reconstructed in 1742 from the old Arab gate that provided access to the medina by the southwest.

After crossing this bridge, I wander the charming old Moorish quarter with its winding pedestrian streets, white-washed houses, and historic squares. Locally known as La Ciudad (The City), the old quarter is situated on the south side of the gorge as opposed to the newer city on the north. Not for from Puente Nuevo in the historic quarter is an interesting gate known as Arco de Felipe V (Arch of Philip V.) This emblematic arch or gate, crowned by three pinnacles, was reconstructed in 1742 from the old Arab gate that provided access to the medina by the southwest.

Next I decide to visit the 14th century Alminar (minaret) of San Sebastián in the old Moorish quarter. The impressive square tower is all that remains of a mosque that once stood here before it was destroyed and rebuilt by the Christians. The lower part is clearly Moorish in architecture while the top part was added by the Christians to house the bell tower of the San Sebastián Church that also once stood here.

Next I decide to visit the 14th century Alminar (minaret) of San Sebastián in the old Moorish quarter. The impressive square tower is all that remains of a mosque that once stood here before it was destroyed and rebuilt by the Christians. The lower part is clearly Moorish in architecture while the top part was added by the Christians to house the bell tower of the San Sebastián Church that also once stood here. Near the minaret is the early 14th century Casa de Mondagrón that is also well worth visiting. The stone palace, promoted as “probably the most important civil monument in Ronda”, was the former residence of a king and its last Muslim governor. In 1485, Ronda was captured by the Christians and a few years later, King Fernando and Queen Isabella also made this palace their home. Although restored and enlarged during the 18th century, the exterior pales in comparison to the beauty of its interior adorned with arched patios, ceramic tiles, marble columns, balconies overlooking at inner courtyards, decorated fountains and water gardens. Today it also houses an auditorium and a municipal museum on the second floor.

Near the minaret is the early 14th century Casa de Mondagrón that is also well worth visiting. The stone palace, promoted as “probably the most important civil monument in Ronda”, was the former residence of a king and its last Muslim governor. In 1485, Ronda was captured by the Christians and a few years later, King Fernando and Queen Isabella also made this palace their home. Although restored and enlarged during the 18th century, the exterior pales in comparison to the beauty of its interior adorned with arched patios, ceramic tiles, marble columns, balconies overlooking at inner courtyards, decorated fountains and water gardens. Today it also houses an auditorium and a municipal museum on the second floor. Ronda is also the birthplace of bullfighting. Not only was the first professional bullfighter born here in 1754 but it is also home of the oldest and largest bullfighting ring in the country dated to 1785. Another unique and unusual aspect of Ronda is their fascination with bandoleros (bandits); particularly those between the 18th and 19th centuries.

Ronda is also the birthplace of bullfighting. Not only was the first professional bullfighter born here in 1754 but it is also home of the oldest and largest bullfighting ring in the country dated to 1785. Another unique and unusual aspect of Ronda is their fascination with bandoleros (bandits); particularly those between the 18th and 19th centuries.

The origins of the city can be traced all the way to the Romans. The Roman Emperor Diocletian, who lived in the 4th century AD, wanted to build himself a retirement mansion. He liked the area of today’s Split for its natural beauties and the warm Adriatic Sea, so he had it built there. In the centuries that followed, the city of Split grew around it, even after the Romans were long gone. The Palace and its surroundings eventually become the historical city core of Split (or Split Old Town), and nowadays the remains of the Diocletian’s Palace are among the best preserved remains of a Roman palace in the world. It was included in the register of the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage in 1979, and is even featured on Croatian banknotes. Built in an irregular rectangle, it was a combination of a luxurious villa and a military camp. Its walls and the center court, the Peristyle, now housing various vendors and souvenir shops, can be explored freely by tourists. However, a tour through its cellar includes a 5 Euro entrance fee.

The origins of the city can be traced all the way to the Romans. The Roman Emperor Diocletian, who lived in the 4th century AD, wanted to build himself a retirement mansion. He liked the area of today’s Split for its natural beauties and the warm Adriatic Sea, so he had it built there. In the centuries that followed, the city of Split grew around it, even after the Romans were long gone. The Palace and its surroundings eventually become the historical city core of Split (or Split Old Town), and nowadays the remains of the Diocletian’s Palace are among the best preserved remains of a Roman palace in the world. It was included in the register of the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage in 1979, and is even featured on Croatian banknotes. Built in an irregular rectangle, it was a combination of a luxurious villa and a military camp. Its walls and the center court, the Peristyle, now housing various vendors and souvenir shops, can be explored freely by tourists. However, a tour through its cellar includes a 5 Euro entrance fee. A city of such interesting history has several museums and galleries in which parts of that history are exhibited. For instance, the Gallery of Fine Arts contains works spanning through six centuries, thus providing an overview of artistic movements in Split and Croatia. Founded in 1931, it houses one of the greatest exhibitions of paintings and sculpture by major Croatian artists, but dedicating space to contemporary art as well.

A city of such interesting history has several museums and galleries in which parts of that history are exhibited. For instance, the Gallery of Fine Arts contains works spanning through six centuries, thus providing an overview of artistic movements in Split and Croatia. Founded in 1931, it houses one of the greatest exhibitions of paintings and sculpture by major Croatian artists, but dedicating space to contemporary art as well.

The cuisine of Split and the surrounding area is heavily based on seafood; fish, clams, oysters are usually boiled or grilled and served with vegetables or potato. Local delicacies include grilled sardines, the octopus salad, or the special kind of dry ham called “prsut”. Served with local wine, the food is usually not spicy, but some restaurants, drawing influences from other Mediterranean countries, started adding exotic spices to traditional Dalmatian dishes, giving them a new spin. For classic local delicacies search for a “konoba” sign, denoting a family-owned tavern specialized in authentic dishes. Of course, if you’re not a lover of seafood, there are plenty of fast food joints in every part of the city.

The cuisine of Split and the surrounding area is heavily based on seafood; fish, clams, oysters are usually boiled or grilled and served with vegetables or potato. Local delicacies include grilled sardines, the octopus salad, or the special kind of dry ham called “prsut”. Served with local wine, the food is usually not spicy, but some restaurants, drawing influences from other Mediterranean countries, started adding exotic spices to traditional Dalmatian dishes, giving them a new spin. For classic local delicacies search for a “konoba” sign, denoting a family-owned tavern specialized in authentic dishes. Of course, if you’re not a lover of seafood, there are plenty of fast food joints in every part of the city. During the summer tourist season the local nightlife flourishes, especially along the Bacvice beachside, featuring several late-opening clubs and beach bars. But the city is big and diverse enough for anyone, with different clubs playing vastly different music. Electronic music lovers should proceed to the minimally decorated Quasimodo, Split’s top venue for DJ nights, or the Jungla (Hula Hula), playing house and techno music. Rock lovers should visit the Kocka or Judino Drvo, where local bands often perform. O’ Hara Music Club is popular among tourists, due to its attractive location at the Zenta waterfront; hosting great parties, it’s great for dancing and drinking. Also, a plethora of bars can be found at the main city promenade, locally known as Riva, which is a great place for slow walks among the rows of palm trees with the incredible view of turquoise Adriatic Sea.

During the summer tourist season the local nightlife flourishes, especially along the Bacvice beachside, featuring several late-opening clubs and beach bars. But the city is big and diverse enough for anyone, with different clubs playing vastly different music. Electronic music lovers should proceed to the minimally decorated Quasimodo, Split’s top venue for DJ nights, or the Jungla (Hula Hula), playing house and techno music. Rock lovers should visit the Kocka or Judino Drvo, where local bands often perform. O’ Hara Music Club is popular among tourists, due to its attractive location at the Zenta waterfront; hosting great parties, it’s great for dancing and drinking. Also, a plethora of bars can be found at the main city promenade, locally known as Riva, which is a great place for slow walks among the rows of palm trees with the incredible view of turquoise Adriatic Sea.

The Palace is also the location of the annual Festival of Flowers (usually held in May), where exhibitors display their flower arrangements based on a particular theme. Visually stunning, it’s a must-visit if you’re in the city at that time. If you’re interested in Roman culture, you’ll be happy to hear that there’s a whole festival dedicated to it. The Days of Diocletian are usually held in late August, and the entire area of the Palace becomes a living monument to the Romans, featuring their cuisine, lifestyle, clothing and customs. Entertaining and educational at the same time, the Days of Diocletian are especially popular with kids.

The Palace is also the location of the annual Festival of Flowers (usually held in May), where exhibitors display their flower arrangements based on a particular theme. Visually stunning, it’s a must-visit if you’re in the city at that time. If you’re interested in Roman culture, you’ll be happy to hear that there’s a whole festival dedicated to it. The Days of Diocletian are usually held in late August, and the entire area of the Palace becomes a living monument to the Romans, featuring their cuisine, lifestyle, clothing and customs. Entertaining and educational at the same time, the Days of Diocletian are especially popular with kids.