by Talisker Donahue

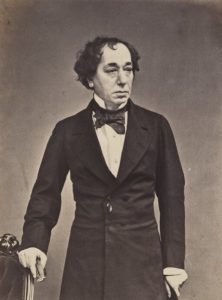

Benjamin Disraeli visited Jerusalem in 1831, at the age of twenty six, hoping to find inspiration for his novel Alroy. The city was to prove the highlight of his Grand Tour, indeed he could have written “half a dozen sheets on this week, the most delightful of all our travels.” [1] The weather was glorious and Disraeli dined “every day on the roof of [his] house by moonlight” [2] after playing at the intrepid nineteenth century tourist and respectable British pilgrim. He was wined and dined by the social powers and he visited the Tombs of the Kings and the Holy Sepulchre. He was, in essence, representative of the supposed two thousand traveller-authors who visited Palestine between 1800 and 1878 [3] and whose impressions were refracted through their biblical and historical education. The majority paid little or no attention to the reality of the Holy Land instead taking their cues from literary antecedents, especially, of course, the Bible. In 1837 for example Lord Lindsay Crawford wrote home to his mother that he “had tried every spot pointed out as the scene of Scriptural events by the words of the Bible, the only safe guide-book in this land of ignorance and superstition.” [4] In instances such as this we can see Orientalism [5] in practice and observe the effect that this innate, largely xenophobic, attitude had on the British view of the Holy Land. For these writers “the real Palestine was the one described in the books rather than the one they saw before them.” [6]

While some, such as Said and Nassar, see Disraeli’s literary output as a product of the Orientalist discourse we can see a certain realisation, especially evident in Tancred, of the cosmopolitan and universally valid nature of Jerusalem and its inhabitants.

This novel, the third in Disraeli’s Young England Trilogy, tells the story of a young aristocrat who, having lost faith in “politics as the means for exerting beneficial change” [7] goes “in search of the wisdom of the three great Asian religions: Christianity, Judaism and Islam.” [8] Of course this to be found in Jerusalem and so Tancred seeks to emulate his crusader forbears by making pilgrimage to the Holy Land, not in conquest but in self-realisation. He does not seek to free Palestine but his own spirit,

This novel, the third in Disraeli’s Young England Trilogy, tells the story of a young aristocrat who, having lost faith in “politics as the means for exerting beneficial change” [7] goes “in search of the wisdom of the three great Asian religions: Christianity, Judaism and Islam.” [8] Of course this to be found in Jerusalem and so Tancred seeks to emulate his crusader forbears by making pilgrimage to the Holy Land, not in conquest but in self-realisation. He does not seek to free Palestine but his own spirit,

“I, too, would kneel at that tomb; I, too, surrounded by the holy hills and sacred groves of Jerusalem, would relieve my spirit from the bale that bows it down; would lift up my voice to heaven, and ask, what is duty, and what is faith? [9]

Tancred, in his realisation that the political world has failed in its cosmopolitan duty of promoting beneficence, becomes drawn to the concept of cross cultural philosophical validity. Away from the machinations of the state, where men like Palmerston “will never rest” until they “get Jerusalem” [10] because, after all, “the English must have markets” [11] Tancred begins to comprehend homogeneity between the East and West, and, indeed, the appeal of such hybridity. This is best demonstrated through Tancred’s relationship with the various indigenous inhabitants of Jerusalem and, especially, the Jewish Eva.

Tancred first meets this woman whose beauty is almost primeval, “such as it existed in Eden” [12]. Her very name is reminiscent of Eve; she is ‘woman’ before she is Jew and she bears the best features of all the nations of Earth.

“[Her] complexion was neither fair nor dark, yet it possessed the brilliancy of the north without its dryness, and the softness peculiar to the children of the sun without its moisture.” [13]

Her cosmopolitan visage is reflected in her conversation when Tancred engages her in a discussion of religion and she states that perhaps she ought to worship Jesus as he is of her race. Indeed Eva has read the Bible and, for Tancred, her mentality is a hybrid mix of Judaism and Anglicanism, she is “already half a Christian.” [14] Tancred though has not yet received his cosmopolitan epiphany and his advice of turning to the church for guidance is met with… un-enthusiasm.

Her cosmopolitan visage is reflected in her conversation when Tancred engages her in a discussion of religion and she states that perhaps she ought to worship Jesus as he is of her race. Indeed Eva has read the Bible and, for Tancred, her mentality is a hybrid mix of Judaism and Anglicanism, she is “already half a Christian.” [14] Tancred though has not yet received his cosmopolitan epiphany and his advice of turning to the church for guidance is met with… un-enthusiasm.

While there is a heady mix of Christian cultures in Jerusalem: Latin, Abyssinian, Armenian, Coptic, Maronite, Greek, this plurality fails as a guide to knowledge. Even divine inspiration, which Tancred is certain he will receive in Jerusalem of all places, is a last resort, to be taken only after “human wit” [15] is exhausted. Eva essentially personifies the spirit of intellectual cosmopolitanism, in both her appearance and outlook. Her morality is not to discovered though scriptural and dogmatic alchemy but rather through rationalistic inquiry.

It is not just in the Holy Land’s inhabitants that Tancred, and Disraeli, find a cosmopolitan identity. The very nature of the place as the cradle of civilisation stirs in the pilgrim the sense that he is treading on ground belonging to humanity. For Tancred, all the natural beauty and wonder of Jerusalem and Palestine pale into insignificance when set alongside the sites of human endeavour and identity,

“[his] eye seized on Sion and Calvary; the gates of Bethlehem and Damascus; the hill of Titus; the Mosque of Mahomet and the tomb of Christ” [16] In seeing this hybrid mix of man’s history he realises that “the view of Jerusalem is the history of the world; it is more, it is the history of Earth and Heaven.” [17]

Tancred’s impression of the universality of the Holy Land is further enhanced during his excursion to Sinai where he observes “two ruins, a Christian church and a Mahometan mosque. In this, the sublimest scene of Arabian glory, Israel and Ishmael alike raised their altars to the great God of Abraham” [18] This coexistence, this acceptance of the holy land as a shared space, awakens in Tancred the understanding that “it is Arabia alone that can regenerate the world.” [19] For Proudman, Disraeli here, is really the antithesis of Said’s Orientalist; “whatever else he was trying to do, Disraeli was not portraying an inferior East,” [20] rather, his multicultural view of religion and Jerusalem reflect the cosmopolitan spirit of the region in spite of politics and statecraft.

Tancred’s impression of the universality of the Holy Land is further enhanced during his excursion to Sinai where he observes “two ruins, a Christian church and a Mahometan mosque. In this, the sublimest scene of Arabian glory, Israel and Ishmael alike raised their altars to the great God of Abraham” [18] This coexistence, this acceptance of the holy land as a shared space, awakens in Tancred the understanding that “it is Arabia alone that can regenerate the world.” [19] For Proudman, Disraeli here, is really the antithesis of Said’s Orientalist; “whatever else he was trying to do, Disraeli was not portraying an inferior East,” [20] rather, his multicultural view of religion and Jerusalem reflect the cosmopolitan spirit of the region in spite of politics and statecraft.

In 2008, when discussing Jerusalem being voted Arab capital of culture, Huda Imam described the city as the “world capital of humanity and spirituality.” [21] As she took around fifty children on a tour of the city one Muslim child asked whether he could pray at the church of the Holy Sepulchre,

“You can pray anywhere you want… Since my childhood, I have always loved to light a candle, recite the fatiha, and make a wish when I visit this church. As a Jerusalemite, I consider it part of my culture” she replied. [22]

This is Jerusalem beneath the politics and at its cosmopolitan best.

Footnotes

[1] Disraeli. Home Letters Written by the Late Earl of Beaconsfield in 1830 and 1831. p.120. Kessinger Publishing Co. Kila, (MT, USA). 2004.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ben-Arieh. Rediscovery of the Holy Land in the Nineteenth Cenuty. p.15. Magnes Press. Jerusalem (Israel). 1983.

[4] Lord Lindsay. Letters on Egypt, Edom and the Holy Land. p.243. Henry Colburn Publishers. London (UK). 1847.

[5] See Edward Said’s Orientalism.

[6] Nassar, I. In their Image: Jerusalem in Nineteenth-Century English Travel Narratives. p.8. Jerusalem Quarterly. Issue 19. 2003.

[7] Levine, R.A. Disraeli’s Tancred and “The Great Asian Mystery”. p.75. Nineteenth-Century Fiction. Vol.22. no.1. 1967.

[8] Proudman, M.F. Disraeli as an ‘Orientalist’: The Polemical Errors of Said. p.551 The Journal of the Historical Society. Vol.5. no.4. 2005.

[9] Disraeli, B. Tancred. p.55. Longmans Green and Co. London (UK). 1871.

[10] Tancred. p.478.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid. p.187

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid. p.189

[15] Ibid. p.190.

[16] Ibid. p.184.

[17] Ibid.

[17] Ibid. p.288-89

[18] Ibid. p.465

[19] Proudman, M.F. 2005. p.555.

[20] Imam, H. Jerusalem: A World of Culture. This Week in Palestine. Issue 123. 2008. thisweekinpalestine.com (Accessed 18/04/12)

[21] Ibid.

Further Information:

Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881) visited Jerusalem in 1831 as part of a ‘Grand Tour’.

♦Born a Jew he was baptised into the Anglican Church and served as the Conservative Prime Minister of England twice between 1868 and 1880.

♦He was a prolific writer before entering politics and wrote several novels, the best known being Vivian Grey (1826), Alroy (1833) and the Young England Trilogy Sybil, Coningsby and Tancred written in the 1840’s.

♦For more information on Disraeli’s adventures in Europe and the Middle East see Robert Blake’s Disraeli’s Grand Tour: Benjamin Disraeli and the Holy Land 1830-31.

♦The best account of Jerusalem’s History is definitely S.S Montefiore’s recent book Jerusalem: The Biography.

Photo credits:

Jerusalem by Walkerssk from Pixabay

Benjamin Disraeli by Unknown photographer / Public domain

Jerusalem street by Dave Herring on Unsplash

Old Jerusalem market by Terrazzo / CC BY

About the author:

Talisker Donahue studied History & Classical civilisation at Roehampton University (London) winning the Humanities Department prize for outstanding academic achievement in the process. Before going to University he made a two month solo trip across Europe and Asia, sleeping in trains, tents and hostels. Tal has also made several other low-budget, big-adventure trips into Europe including Italy, Germany and France. He has ambitions to compile a guide to ‘shoestring travel’ for students in addition to freelance history writing.

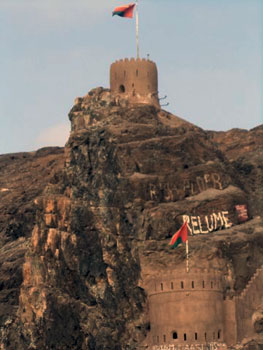

The discovery of oil however has given the country an unprecedented economical boost and it is my very personal opinion that the wealthy past has determined that the billions of petro dollars have been put to brilliant use. There is absolutely nothing ‘nouveau riche’ about modern Muscat. The difference to nearby Dubai is striking. Muscat has only one high rise, the Hilton Hotel and that has only 14 stories. Otherwise the buildings have all been designed in traditional Omani style with round towers, huge walls, carved wooden doors and small windows to keep out the heat. The only colors in evidence are white and sand, no garish paint, no gold, no colorful tiles, no adornment other than stone arabesques carved into the mantels. The overall impression is of cool elegance and understated wealth. Very, very soothing on the eye and beautifully in harmony with the country.

The discovery of oil however has given the country an unprecedented economical boost and it is my very personal opinion that the wealthy past has determined that the billions of petro dollars have been put to brilliant use. There is absolutely nothing ‘nouveau riche’ about modern Muscat. The difference to nearby Dubai is striking. Muscat has only one high rise, the Hilton Hotel and that has only 14 stories. Otherwise the buildings have all been designed in traditional Omani style with round towers, huge walls, carved wooden doors and small windows to keep out the heat. The only colors in evidence are white and sand, no garish paint, no gold, no colorful tiles, no adornment other than stone arabesques carved into the mantels. The overall impression is of cool elegance and understated wealth. Very, very soothing on the eye and beautifully in harmony with the country. Already in love with the serene beauty of modern Muscat, my friend and I decided to visit the Muttrah souk, one of the oldest souks in all of the Middle East. During Ramadan, the souk is only open at night and, as Eid was approaching, people were out in doves to shop for clothes, jewelry and gifts in preparation for the festivities marking the end of the holy month. Two things held our attention: the ever present scent of frankincense which burns in every doorway and is one of the most important items on offer and the beautifully carved roof, reflecting the age old art of Omani wood carvings. In fact, so important is frankincense to Oman that a huge burner, high up on a hill is one of the most famous landmarks of Muscat.

Already in love with the serene beauty of modern Muscat, my friend and I decided to visit the Muttrah souk, one of the oldest souks in all of the Middle East. During Ramadan, the souk is only open at night and, as Eid was approaching, people were out in doves to shop for clothes, jewelry and gifts in preparation for the festivities marking the end of the holy month. Two things held our attention: the ever present scent of frankincense which burns in every doorway and is one of the most important items on offer and the beautifully carved roof, reflecting the age old art of Omani wood carvings. In fact, so important is frankincense to Oman that a huge burner, high up on a hill is one of the most famous landmarks of Muscat. The next day we wanted to explore Muscat some more and also visit the part known as Old Muscat. To our disappointment, there is next to no public transport. We love to travel on local buses. But, at a price of 50cents for a liter of gas it doesn’t come as a surprise that everybody has at least one car. So, we took a taxi, passing by the modern, exquisite shopping complex in Ruwi on our way to the Sultan’s palace. It’s the only colorful building in blue and gold with nearly identical front and back which can be seen from the landside as well as from the water.

The next day we wanted to explore Muscat some more and also visit the part known as Old Muscat. To our disappointment, there is next to no public transport. We love to travel on local buses. But, at a price of 50cents for a liter of gas it doesn’t come as a surprise that everybody has at least one car. So, we took a taxi, passing by the modern, exquisite shopping complex in Ruwi on our way to the Sultan’s palace. It’s the only colorful building in blue and gold with nearly identical front and back which can be seen from the landside as well as from the water. The first took us out to sea to watch dolphins at play, the second along the breath taking coastline with alternating rock formations in white marble and black granite with tiny sand beaches in between. Boat trip #3 was dedicated to experiencing the coastline bathed in the rays of the sinking sun on board a traditional Oman dhow.

The first took us out to sea to watch dolphins at play, the second along the breath taking coastline with alternating rock formations in white marble and black granite with tiny sand beaches in between. Boat trip #3 was dedicated to experiencing the coastline bathed in the rays of the sinking sun on board a traditional Oman dhow.

Out of the corner of my eye I caught a peek of al-Khazneh (the Treasury). With each step, the Treasury came closer and closer until finally I stood in front of this royal tomb carved into the rock. Built sometime between 100 BCE and 200 CE, the tomb got its name from the legend that pirates hid their treasure in a giant stone urn. Bullet holes on the urn indicate that the Bedouins believed this myth and made numerous attempts to retrieve this booty.

Out of the corner of my eye I caught a peek of al-Khazneh (the Treasury). With each step, the Treasury came closer and closer until finally I stood in front of this royal tomb carved into the rock. Built sometime between 100 BCE and 200 CE, the tomb got its name from the legend that pirates hid their treasure in a giant stone urn. Bullet holes on the urn indicate that the Bedouins believed this myth and made numerous attempts to retrieve this booty.

After lunch, I rode up to al-Deir (the Monastery) on donkeys. The thought of climbing up eight hundred steep steps as the temperature hovered near 100 degrees didn’t sound appealing. Horses and camels balk at this almost vertical climb, but donkeys can do it. As the path narrowed and steepened, my stomach felt a bit like it did the first time I rode the Coney Island Cyclone. Still, my donkey never missed a step, stopping only to relieve himself. (My sympathy for those who chose to walk to the monastery, because the path was littered with donkey dung.)

After lunch, I rode up to al-Deir (the Monastery) on donkeys. The thought of climbing up eight hundred steep steps as the temperature hovered near 100 degrees didn’t sound appealing. Horses and camels balk at this almost vertical climb, but donkeys can do it. As the path narrowed and steepened, my stomach felt a bit like it did the first time I rode the Coney Island Cyclone. Still, my donkey never missed a step, stopping only to relieve himself. (My sympathy for those who chose to walk to the monastery, because the path was littered with donkey dung.)

We find Souq Waqif (market) the perfect place to soak up tradition, with a bonus of both outdoor sections and those sheltered from Old Sol. Waqif has been around since the days when Bedouin nomads traded goats, sheep and wool for essential items. Restorations have not changed the maze of passageways with mud rendered walls and wood beamed ceilings. We meander past small shops piled high with spices, dates, figs, perfumes, pots, dishes, plastic everything, aquarium fishes, birds, puppies, and bunnies. A father passes with his small daughter clinging to his one hand, while in the other he carries his purchase – a falcon. The ancient art of Falconry dates back to at least the 7th century BC, and although Westerners find using these birds of prey for sport objectionable, it is prevalent in the Arab countries and the Bedu are the grand masters.

We find Souq Waqif (market) the perfect place to soak up tradition, with a bonus of both outdoor sections and those sheltered from Old Sol. Waqif has been around since the days when Bedouin nomads traded goats, sheep and wool for essential items. Restorations have not changed the maze of passageways with mud rendered walls and wood beamed ceilings. We meander past small shops piled high with spices, dates, figs, perfumes, pots, dishes, plastic everything, aquarium fishes, birds, puppies, and bunnies. A father passes with his small daughter clinging to his one hand, while in the other he carries his purchase – a falcon. The ancient art of Falconry dates back to at least the 7th century BC, and although Westerners find using these birds of prey for sport objectionable, it is prevalent in the Arab countries and the Bedu are the grand masters. In a Sheesha 101 lesson Hussein demonstrates the basics. Billows of smoke rise into the air with each puff. Rick tries next. With my camera aimed, I wait…and wait for a billow…ahhh, at last, a pouf of smoke the size of a walnut. “Not as easy as it looks,” claims Rick, as Hussein cheers, “Way to go!”

In a Sheesha 101 lesson Hussein demonstrates the basics. Billows of smoke rise into the air with each puff. Rick tries next. With my camera aimed, I wait…and wait for a billow…ahhh, at last, a pouf of smoke the size of a walnut. “Not as easy as it looks,” claims Rick, as Hussein cheers, “Way to go!” As we approach the track, my heart leaps at the sight of these ships of the desert everywhere; in compounds along the roadway, and strings of them crisscrossing the highway bringing traffic to a halt. We pull into the Al-Shahaniya complex and gleefully make our way to the track. Practicing jockeys and camels in bunches race by stirring up clouds of dust. Some of the jockeys bouncing along on an adult camel also hold the reins of a juvenile camel with no rider; no doubt a learning process for the gangly young’un.

As we approach the track, my heart leaps at the sight of these ships of the desert everywhere; in compounds along the roadway, and strings of them crisscrossing the highway bringing traffic to a halt. We pull into the Al-Shahaniya complex and gleefully make our way to the track. Practicing jockeys and camels in bunches race by stirring up clouds of dust. Some of the jockeys bouncing along on an adult camel also hold the reins of a juvenile camel with no rider; no doubt a learning process for the gangly young’un.

Back in Doha we see more evidence of the country’s wealth in the stadiums of Sport City, built for the 2006 Asian Games, the largest ever held. At the nearby Villagio Mall Jerri says, “the extravagance must be seen to be believed”. Shoppers take time for a gondola ride along the faux-Venetian canal running through the middle of the mall’s ultra-wide corridors. A gigantic food court overlooks an ice rink where a hockey game is in progress; the skating finesse and puck-handling of the players aged 12 to 14 years is top-notch.

Back in Doha we see more evidence of the country’s wealth in the stadiums of Sport City, built for the 2006 Asian Games, the largest ever held. At the nearby Villagio Mall Jerri says, “the extravagance must be seen to be believed”. Shoppers take time for a gondola ride along the faux-Venetian canal running through the middle of the mall’s ultra-wide corridors. A gigantic food court overlooks an ice rink where a hockey game is in progress; the skating finesse and puck-handling of the players aged 12 to 14 years is top-notch. Being Friday, the first day of the Muslim weekend, the mall is wall-to-wall with congregations of family and friends. In the multi-cultural mix of a population of 900,000, 75% are expatriates from around the world employed in jobs ranging from janitors to CEOs. Qataris make up the remaining 25% and are distinguishable by their dress and apparent affluence. Rolex watches peek from the sleeves of men’s impeccable white throbe (floor-length shirt-dress) as they twirl a set of prayer beads between thumb and forefinger, which may be made of pearls, jade, or gold nuggets. Their gutra (white head cloth) secured by black-tasselled head-rope called an agal looks dashing. Women’s abeyyas (black robes) and hejabs (head scarves) are trimmed with gold, silver or gems; their fingers and wrists flash diamonds the size of marbles as they tote bags with purchases from top-fashion designers. Seeing a Lamborghini with gold wheel rims as we left the mall is the ultimate in excess.

Being Friday, the first day of the Muslim weekend, the mall is wall-to-wall with congregations of family and friends. In the multi-cultural mix of a population of 900,000, 75% are expatriates from around the world employed in jobs ranging from janitors to CEOs. Qataris make up the remaining 25% and are distinguishable by their dress and apparent affluence. Rolex watches peek from the sleeves of men’s impeccable white throbe (floor-length shirt-dress) as they twirl a set of prayer beads between thumb and forefinger, which may be made of pearls, jade, or gold nuggets. Their gutra (white head cloth) secured by black-tasselled head-rope called an agal looks dashing. Women’s abeyyas (black robes) and hejabs (head scarves) are trimmed with gold, silver or gems; their fingers and wrists flash diamonds the size of marbles as they tote bags with purchases from top-fashion designers. Seeing a Lamborghini with gold wheel rims as we left the mall is the ultimate in excess.

Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem on a colt fulfilled the prophecy of Zechariah (Zechariah 9:9). As he descended the Mount of Olives, he stopped and looked out over the city. Jesus wept upon seeing the Holy Temple across the Kidron Valley (Luke 19:41-44) because he knew that Jerusalem would be destroyed – and it came to pass in 70 CE. This event is commemorated half way down the Mount of Olives where you find the “tear drop”-shaped Church of the Dominus Flevit (Latin for “the Lord Wept”).

Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem on a colt fulfilled the prophecy of Zechariah (Zechariah 9:9). As he descended the Mount of Olives, he stopped and looked out over the city. Jesus wept upon seeing the Holy Temple across the Kidron Valley (Luke 19:41-44) because he knew that Jerusalem would be destroyed – and it came to pass in 70 CE. This event is commemorated half way down the Mount of Olives where you find the “tear drop”-shaped Church of the Dominus Flevit (Latin for “the Lord Wept”). Entering the church, your eyes are immediately drawn to the arch-shaped picture window behind the altar. Those attending mass might be forgiven (hopefully) for being distracted by the magnificent view of the Old City of Jerusalem set within the window frame. The Dome of the Rock and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are both conspicuous in this picture.

Entering the church, your eyes are immediately drawn to the arch-shaped picture window behind the altar. Those attending mass might be forgiven (hopefully) for being distracted by the magnificent view of the Old City of Jerusalem set within the window frame. The Dome of the Rock and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are both conspicuous in this picture. Before he was betrayed, Jesus visited the Garden of Gethsemane to pray (Matthew 26:30, Mark 14:32, Luke 22:12, John 13:1). Located at the foot of the Mount of Olives, the Garden of Gethsemane showcases the Basilica of the Agony with its mosaic façade depicting Jesus as the mediator between God and man.

Before he was betrayed, Jesus visited the Garden of Gethsemane to pray (Matthew 26:30, Mark 14:32, Luke 22:12, John 13:1). Located at the foot of the Mount of Olives, the Garden of Gethsemane showcases the Basilica of the Agony with its mosaic façade depicting Jesus as the mediator between God and man. Inside the basilica, dark alabaster windows set the sombre mood for the agony and betrayal of Jesus. The flat “Stone of Agony” near the altar marks the spot where Jesus sweated blood (Luke 22:44) as he prayed. A mosaic behind the altar preserves that moment in time.

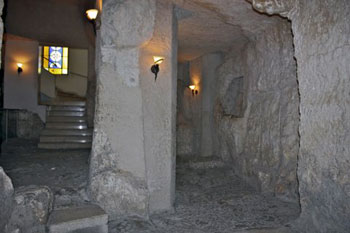

Inside the basilica, dark alabaster windows set the sombre mood for the agony and betrayal of Jesus. The flat “Stone of Agony” near the altar marks the spot where Jesus sweated blood (Luke 22:44) as he prayed. A mosaic behind the altar preserves that moment in time. Also on the site of the original Antonia Fortress, the Franciscan Monastery is located opposite the Al-Omariya School on the Via Dolorosa. This monastery houses both the Church of the Flagellation and Church of the Condemnation (the 2nd Station of the Cross).

Also on the site of the original Antonia Fortress, the Franciscan Monastery is located opposite the Al-Omariya School on the Via Dolorosa. This monastery houses both the Church of the Flagellation and Church of the Condemnation (the 2nd Station of the Cross). The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the holiest site in Christendom, is the traditional site of the crucifixion and tomb of Jesus. Enter the church and climb the well-worn stairs immediately to your right to the top of Golgotha/Calvary (Matthew 23:35, Mark 15:22, Luke 23:33, John 19:17). Here you enter the Roman Catholic Chapel of the Nailing of the Cross – the 11th Station of the Cross.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the holiest site in Christendom, is the traditional site of the crucifixion and tomb of Jesus. Enter the church and climb the well-worn stairs immediately to your right to the top of Golgotha/Calvary (Matthew 23:35, Mark 15:22, Luke 23:33, John 19:17). Here you enter the Roman Catholic Chapel of the Nailing of the Cross – the 11th Station of the Cross. Join the line to enter the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre inside the Edicule – the 14th Station of the Cross. Inside you find a reconstructed slab on your right consisting of two marble stones. A vase with candles marks the spot where Jesus’ head once rested.

Join the line to enter the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre inside the Edicule – the 14th Station of the Cross. Inside you find a reconstructed slab on your right consisting of two marble stones. A vase with candles marks the spot where Jesus’ head once rested.

Set on a sheer hillside, the Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu is the traditional the site of the High Priest Caiaphas’ house. Jesus was brought before Caiaphas immediately after his arrest (Luke 22:54, Mark 14:54, John 18:24, Matthew 26:57). You can easily find this church by looking for the roof with a golden rooster set on top of a cross. The rooster identifies this as the site where Peter denied Christ three times before the cock crowed (Matthew 26:69-75, Mark 14:66-72, Luke 22:55-62, John 18:25-27) hence the name “Gallicantu” (Latin for “the cock’s crow”). A statue in the courtyard depicts the event.

Set on a sheer hillside, the Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu is the traditional the site of the High Priest Caiaphas’ house. Jesus was brought before Caiaphas immediately after his arrest (Luke 22:54, Mark 14:54, John 18:24, Matthew 26:57). You can easily find this church by looking for the roof with a golden rooster set on top of a cross. The rooster identifies this as the site where Peter denied Christ three times before the cock crowed (Matthew 26:69-75, Mark 14:66-72, Luke 22:55-62, John 18:25-27) hence the name “Gallicantu” (Latin for “the cock’s crow”). A statue in the courtyard depicts the event. The churchyard features a number of ruins including olive presses, a bath house and a stone stairway leading to the Pool of Silwan below. Jesus may have used this stairway as he walked from the Coenaculum to the Garden of Gethsemane by way of the Kidron Valley before his betrayal. Visitors also find a model of the Old City of Jerusalem during the 4th-6th centuries CE. The Temple Mount is conspicuously bare and remained that way until the Dome of the Rock was constructed in 691 CE after the Muslim conquest.

The churchyard features a number of ruins including olive presses, a bath house and a stone stairway leading to the Pool of Silwan below. Jesus may have used this stairway as he walked from the Coenaculum to the Garden of Gethsemane by way of the Kidron Valley before his betrayal. Visitors also find a model of the Old City of Jerusalem during the 4th-6th centuries CE. The Temple Mount is conspicuously bare and remained that way until the Dome of the Rock was constructed in 691 CE after the Muslim conquest.