by Georges Fery

The cluster of valleys on the banks of the Supe River in the north-central coast of Peru, known as the Norte Chico, stands out among other ancient human settlements in the country for the antiquity, number, size, and complexity of its monumental architecture, witnesses to an extraordinary past. Its early urban centers are Banduria (4000-2000BC), Aspero (3700-2500BC), and Caral, also referred to as Caral-Supe (3500-2000BC), which far surpassed the other two in power and influence and has been called “the oldest city in the Americas, and one of the earliest cities in the world” (Mann, 2005). However, unlike cultures in other parts of the world, the Peruvian urbanization took place in total isolation. The rise of civilization in Peru preceded the Olmec civilization, believed to be the oldest in Mesoamerica, by at least 1500 years (Shady, 1994).

Hunting and gathering for subsistence, in what is now Peru’s Norte Chico, is documented as early as 9500-8000BC. Small groups started plant selection and gardening, and the remains of irrigation channels have been dated to that period. New concerns with the cosmos and religion led to the unification of nascent social groups around spiritual concepts. In turn, this collective perception brought social stratification, followed by an economic cooperation that swept the Andes and Northern Peru’s coastal communities (Shady, 1997). Agriculture expanded, and by 3200 BC, harvested cotton was an already important trade crop, used to make nets for fishing, and later net-bags (shicras) employed in construction. Domestication of camelids such as llamas also grew around this time.

Rise and Fall of Ancient Civilizations in Peru

So, let’s follow the field notes of renowned Peruvian archaeologist Ruth Shady Solis and others, to look at how ancient civilizations in this region rose and fell. The fertile Supe River and its affluents wind their way to the coast from the western piedmont of the Andes to the dry coastal plains. Its lush valley is host to twenty-one ancient settlements that share a common architecture and urban distribution dating from the Late Archaic period (3500BC). On the Pacific Coast, at the mouth of the Supe River, is the Late Archaic site of Aspero (3700-2500 BC). This coastal town seems to be the origin of human settlement in this part of the Norte Chico. As demographic pressure increased at Aspero together with social complexity, communities split into groups that moved up the Supe River valley and set up villages upstream. Aspero’s location, however, gave the town a key role in the initial economic development of the region, providing access to the abundant schools of fish that rode the cold northbound Humboldt current, as well as control of the sea salt trade with growing inland communities.

Caral and other close communities were built fourteen miles up the coast in the 60-mile-long Supe River valley, on the arid plateau extending on both banks of a ravine and the fertile but narrow valley where crops were planted. The settlements on the plateau on each of the upper sides of the ravine were thus protected from seasonal floods. In the 3500-3200 BC time frame, Caral (165 acres) grew from a village to a city together with Era de Pando (200 acres) and Pueblo Nuevo (135 acres), while neighboring hamlets such as Cerro Colorado, Liman, or Cerro Blanco did not exceed two or three acres.

Caral Confirmed as Oldest City in the Americas

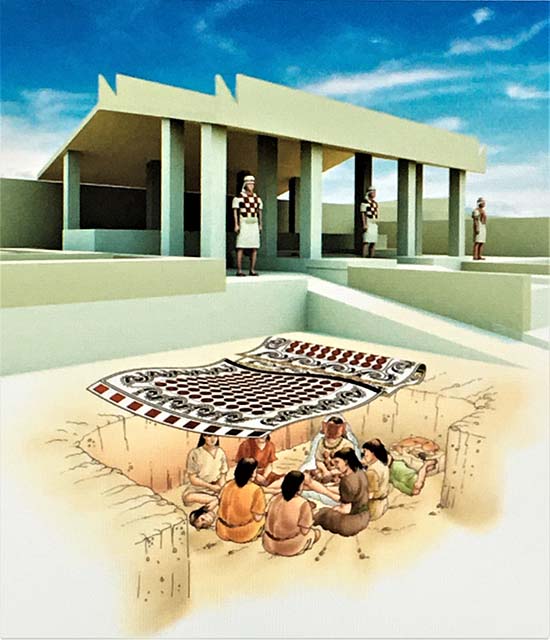

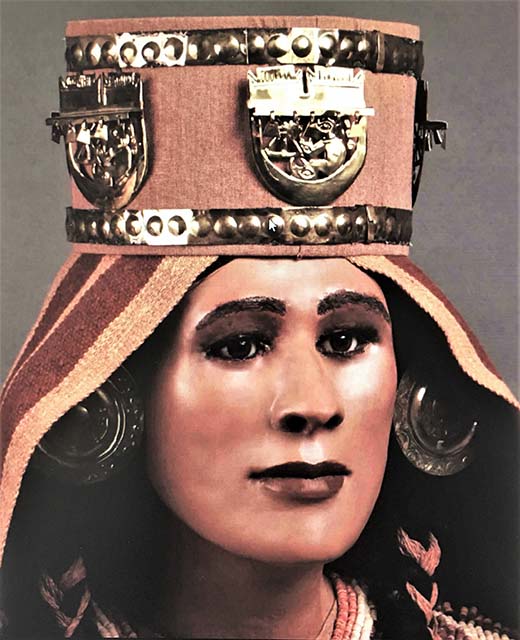

By 3000-2900 BC, Caral was the seat of regional power, with Curacas – or heads of lineages – in control of political, socio-economic, and religious affairs. The foremost Curaca was the principal of a network of districts that spread up from the Pacific coast to the foothills of the Andes, an organization that was based on trade and reciprocity (Shady, Dolorier, Casas, 2000). What kept the network together was religion, used as a means of cohesion and coercion, as well as a symbol of mutual cultural and spiritual identity (Shady, 2004). Today, Caral’s monumental pyramidal stepped structures associated with sunken circular plazas, emphasized its importance as a secular and religious power center. Its seven massive temple-pyramids dot the landscape together with remains of residential complexes large and small. Its antiquity as the oldest in the Americas has been confirmed by 29 radiocarbon dates (Shady, 1993, 2000).

While Caral stands as a significant and renowned archaeological site in Peru, accessing it via public transportation is currently not feasible. However, you can embark on a memorable day trip from Lima to Caral. Join Travel Adventures Peru for a convenient excursion led by knowledgeable local guides.

Caral and its neighboring communities on both sides of the Supe River, may have housed over 20,000 people. Shady stresses, in agreement with Feldman (1980) and Grieder et al. (1988), that “field research indicates that the Caral-Supe society was organized into socially stratified ranks with local authorities connected to a state government, sustained by a productive and diversified crop production and fishing economy.” Farmers cultivated fields irrigated by means of a simple system of canals guiding water from the Supe River and its affluents, as well as from numerous springs.

The socio-economic dynamics were driving internal and external exchanges that allowed for the development of complex technological and social organization. “Caral’s direct control and economic dominance included populations of the Supe, Pativilca and Fortaleza valleys. Its interaction and prestige extended across the entire north-central Peru region from the Andes foothills to the coast. Furthermore, Shady stresses that evidence shows that “Caral was the model of a socio-political organization that other societies achieved only in later times throughout Peru” (2002).

The impressive achievements of Caral’s inhabitants (called Caralinos by archeologists), from architecture to religion is owed to their dynamism, creativity, and interactions with social groups in the upper reaches of the Andes. Caral’s history and culture was closely associated with its ceremonial calendar which was set in harmony with nature and the seasons. However, they were also influenced by two major natural disrupters that are historically associated with the demise of cultures in northern Peru. These disrupters were, still are, inextricably linked to the ebb and flow of Norte Chico cultures. The first of the disrupters are the combined climate episodes triggered by El Niño and La Niña, which affect global weather patterns. In a few words, El Niño is associated with a band of nutrients-poor warm water and atmospheric convection that develops in the east-central equatorial Pacific and spreads to South America’s east coast. ENSO-El Niño Southern Oscillation refers to the cycle of warm and cold Sea Surface Temperature (SST) of the tropical central and eastern Pacific Ocean, with high air pressure in the western Pacific and low air pressure in the eastern Pacific.

El Niño’s moisture-laden clouds produce intense rains, floods, and landslides, devastating cultures and may be, but is not always, followed a year or so later by La Niña, El Niño colder counterpart. During La Niña episodes, strong winds blow warm water on the ocean’s surface away from South America across the Pacific Ocean. SST in the eastern Pacific is, at that time, below average. Cold water from the ocean then rises to the surface near South America’s coast. La Niña is associated with droughts that may last months over the South American continent. These complex occurrences vary in intensity and may recur in cycles of seven or fourteen years.

The second set of disrupters are the earthquakes triggered by the collision of the massive South American tectonic plate and the far heavier Nazca plate as it moves eastward from the Pacific and slides beneath the South American plate. The friction between the plates, in the subduction zone along the Peru-Chile trench, are the main cause of earthquakes and volcanic activity in the region.

To mitigate the disruptive effects of earthquakes, Caralinos found an ingenious way to give their constructions a certain “flexibility” during seismic events. Their answer was the shicra, a net made of cotton mixed with vegetal fibers that was packed with loose rocks. Shicras that held over a thousand pounds of rocks were found in the foundations of structures. Smaller shicras were used to carry stone loads of fifteen to twenty pounds from quarries to building sites, where they were placed in the retaining walls to allow structures to absorb a certain number of disturbances from quakes without damaging the walls.

Together with the shicras, quinchas-lintels or beams made of the huarango, a hard wood of a mesquite tree species such as the “algarrobo blanco” (Prosopis alba), were used to shore up doors and passageways in buildings, along with massive stone pillars as central support. All structures large and small, were built of shaped stone blocs set with mud.

Seven Large Pyramids

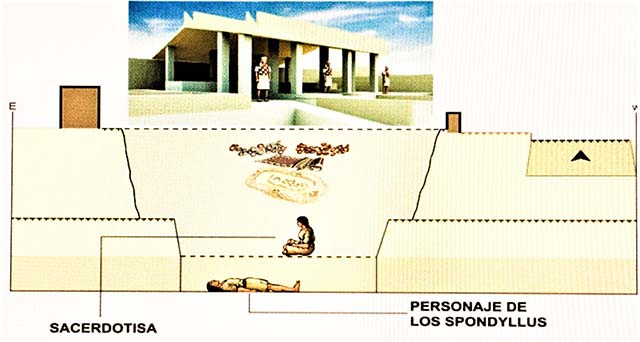

Caral’s thirty-two monumental structures, and its residential complexes large and small, underscore the ancient city’s importance. In the upper half of the city are seven large pyramidal structures, two of them, the Great Pyramid, and the Pyramid of the Amphitheater, are associated with large sunken circular courts. Major structures encircle multifunction open spaces or plazas. There are two subgroups: the one to the west includes the Great Pyramid, the Central Pyramid, the Quarry Pyramid, and the Lesser Pyramid. The subgroup to the east includes the Pyramid of the Amphitheater, the Pyramid of the Gallery, and the Pyramid of the Huanca (a huanca is a tall upright monolith, usually an uncarved stone). The eight-foot-tall huanca is found three hundred feet away from the plaza and the two pyramids, at the end of a causeway.

Archaeologist Shady notes that at Caral “the structures in the nuclear space are grouped into two great halves: an upper half, nearest the water where the most impressive pyramidal structures are located, and a lower half with smaller public buildings, but for one large complex that also has a circular sunken court attached to it” (2002).

This spatial organization likely expresses the Andean binary division into hanan and hurin (upper and lower, respectively). Pyramidal structures vary in size and exhibit distinct elements, but all share a model for the façade, which are comparable in style and design. Shady remarks that “all buildings follow a similar model with superimposed terraces placed at intervals and contained by stone walls. Each façade has fixed stellar direction and an axis that internally divides the space. This axis is usually marked by a staircase traversing the center of the terraces from the base to the summit. The flight of stairs also divides the building into a central body with two left and right extensions, each with rooms and passageways. The central body of each structure consists of segments set apart by their sequential location at specific elevations” (2001).

An exhaustive description of this 5000–year-old city would require far more space than is available here. So, together with archaeologists Shady, Machacuay and Aramburu, we will focus on three major structures: the Great Pyramid (Sector.E), the Pyramid of the Galeria (Sector.I), and the Temple of the Amphitheater (Sector.L). The Great Pyramid is the largest and most extensive and important complex in the upper half (hanan) of the city. It measures 561 feet from east to west and 495 feet from north to south. Its south facing façade is 65-five feet in height while its north side, facing the valley, reaches to slightly less than 100 feet. Its main feature is an important circular sunken court and an imposing stepped pyramidal structure made of a central body and two side components.

An important feature in the structure is that of the Altar of the Sacred Fire, which is located at the top of the pyramid, in a small quarter with a ventilation shaft running below it. The diameter of the circular sunken court, attached to the north side of the pyramid, is 120-feet, and its sunken interior is 72-feet across. An entrance stairway leads up from the exterior and up the south side of the court, in line with the axial staircase of the pyramid. On the north-south axis, two other staircases descend to the court, each framed by two large upright monoliths. The internal wall of the court is made of stone blocks reset one-and-a-half feet to an elevation of five feet giving it a stepped appearance. The walls, stairs and floors of the plaza were plastered and painted. Given its size, location, and association with the circular court, this was probably the city’s main public building” (2000).

The Pyramid la Galeria owes its name to the monolith located about three hundred feet from the pyramid’s main stairway. This pyramid is of a quadrangular plan, located in the east subgroup, at the extreme southeast of the upper half of the city (hanan). The façade is oriented toward the urban space shared with the Pyramid of the Gallery (Sector.H). The eight-foot-high monolith or huanca, seems to have been the axis common to the two buildings. The Pyramid of the Huanca has the typical stepped profile, consisting of five superimposed terraces and four sides. It measures 177 feet on its east-west axis, 171 feet from north to south and reaches 42 feet in height. Its eighteen18-foot-wide central stairway leads at the summit to an atrium, assumed to be an observatory. Notable among the finds in the building, is a headdress made of grassy fiber.

This is Part One of a two-part article about Caral.

Read Part Two Here.

Further Reading:

Ruth Shady Solis, 2001 – The Oldest City in the New World

Jennings, J., 2008 – Catastrophe, Revitalization and Religious Change on the Prehispanic North Coast of Peru

Ruth Shady and Carlos Leyva, 2003 – La Ciudad Sagrado de Caral-Supe

Roxana Hernandez Garcia, 2015 – Caral: 5000 Años de Identidad

Jesús Sánchez Jaén, 2008 – Caral, la Cultura de las Plazas Circulares

Ruth Shady Solis, J. Haas, and W. Creamer, 2001 – Dating Caral, a Preceramic in the Supe Valley on the Central Coast of Peru (Science, 292).

Haas and M. Piscitelli, 2004 – The Rise of Andean Pre-Inca Civilizations

Ruth Shady Solis, 2006 – La Civilización Caral: Sistema Social y Manejo del Territorio y sus Recursos; sus Transcendancia en el Proceso Cultural

Eva Jobbova, Ch. Elmke & A. Bevan, 2018 – Ritual Responses to Drought: An Examination of Ritual Expressions

Arthur D. Faram, 2010 – A Geographic Study of the Ancient Caral, Peru

About the author:

Freelance writer, researcher and photographer, Georges Fery (georgefery.com) addresses topics, from history, culture, and beliefs to daily living of ancient and today’s communities of Mesoamerica and South America. His articles are published online at travelthruhistory.com, ancient-origins.net and popular-archaeology.com, in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com), as well as in the U.K. at mexicolore.co.uk. The author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies instituteofmayastudies.org Miami, FL and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org. As well as member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu, and the NFAA – Non-Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthrosassociation.com.

Contact: Georges Fery – 5200 Keller Springs Road, Apt. 1511, Dallas, Texas 75248, (786) 501 9692 –gfery.43@gmail.com and www.georgefery.com

Photo Credits:

1 – The Great Pyramid courtesy of peruinfo.com

2 – Caral, Site Map courtesy of mdpi.com

3 – Peru Tectonic Plates: Map: USGSDescription:Scott Nash, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

4 – Shicra Nets: I, Xauxa, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

5 – Complex of the Circular Court © georgefery.com

6 – Pyramid la Galeria and the Huanca © georgefery.com