by Thomas Kenning

Hiroshima. The very name conjures powerful images of mushroom clouds and devastation. The city’s atomic past is an integral part of its identity, but it is also a living city with fantastic opportunities for fun, culture, and entertainment. During my recent visit, I had the chance to meditate on a dark past at the Atomic Bomb Dome, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, take in a major league baseball game with the Hiroshima Carp, and participate in the annual lantern ceremony on the banks of the Ota River.

The Hypocenter

My first stop is the hypocenter upon which sixty-six years ago, the world’s first atomic bomb was used against human targets. Aimed at the T-shaped Aioi Bridge near the geographic center of town, wind blew the bomb slightly off course some 500 meters to the southwest where it detonated over Shima Hospital.

My first stop is the hypocenter upon which sixty-six years ago, the world’s first atomic bomb was used against human targets. Aimed at the T-shaped Aioi Bridge near the geographic center of town, wind blew the bomb slightly off course some 500 meters to the southwest where it detonated over Shima Hospital.

Contrary to the assertions of U.S. propaganda and President Harry Truman, Hiroshima was not a military base by any stretch. It was a city of about three hundred thousand, seventy thousand people died instantly, and nearly one hundred fifty thousand died by the end of the year. Of that number, only a few thousand were soldiers. The very fact that U.S. military planners were willing to leave the city untouched for so long testifies to its irrelevance as a military target – it was so unimportant that military planes could afford leave it untouched for the last, grand act of the war.

Hiroshima was singled-out early on during the extensive U.S. firebombing raids against Japan that were ongoing through mid-1945. As such, it was spared any preliminary destruction by incendiary or other conventional bombs. Planners wanted a pristine target to measure the true destructive capabilities of their new weapon. Residents of Hiroshima invented sadly misguided explanations for why their city was spared the devastation that rained down on so many other cities that summer. They speculated that they were granted mercy since a large portion of the Japanese population in the U.S. had emigrated from Hiroshima. Instead, the city was chosen as a target for the atomic bomb based on several criteria, its position on a large, level river delta first among those reasons.

Today, the hypocenter is a narrow street where the reconstructed Shima Hospital stands. A block over is the Hiroshima Peace Park featuring the T-Shaped bridge, the Hiroshima Peace Museum, and, for Americans, the most iconic A-bomb-related image aside from the mushroom cloud itself – the Atomic Bomb Dome, formerly known as the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. As a concrete structure designed and built by Europeans in 1921, it was one of the few buildings left standing in the otherwise wooden city of Hiroshima. Today, though the city around it is modern steel and glass, it stands in ruins, slightly reinforced but largely in the same apocalyptic condition it was in by the end of the day on August 6, 1945. A lot more grass grows around it these days, underscoring the fact that time has passed and that for many, even in Hiroshima, life goes on.

The Hiroshima Carp

I have a special Japanese friend serving as my informal guide on this trip. Her name is Koko, and she is a remarkable woman. She was just eight months old when Hiroshima was destroyed, so has no direct memory of that day. Yet the bomb has shaped and defined her life in many inscrutable ways. Standing not much more than four feet tall with salt-and-pepper hair pulled into a bun, she looks mild, but in relating the story of her journey from infant in the wrong place at the wrong time – the epitome of an innocent bystander – to peace activist and nuclear critic, she speaks with a stirring fervency, translating her Japanese into her own fluent, vivid English.

I have a special Japanese friend serving as my informal guide on this trip. Her name is Koko, and she is a remarkable woman. She was just eight months old when Hiroshima was destroyed, so has no direct memory of that day. Yet the bomb has shaped and defined her life in many inscrutable ways. Standing not much more than four feet tall with salt-and-pepper hair pulled into a bun, she looks mild, but in relating the story of her journey from infant in the wrong place at the wrong time – the epitome of an innocent bystander – to peace activist and nuclear critic, she speaks with a stirring fervency, translating her Japanese into her own fluent, vivid English.

Aside from a brief stint at American University in Washington, DC to earn her bachelor’s degree, Koko has lived all 66 years of her life in Hiroshima. She remembers when, in 1950, just five years after the bomb, in the lean years when families still lived in temporary housing and school was still held outside for lack of standing buildings, the people of Hiroshima scraped together their yen to start a proper baseball team in their city. A testament to the human spirit as well as to the unrivaled Japanese love of baseball.

The Carp are still going strong 61 years later, playing their home games in picturesque Mazda Zoom Zoom Stadium. Most American stadiums are surrounded by several square miles of concrete wasteland devoted to parking every individual spectator’s car. The Carp’s stadium is within easy walking distance of the Toyoko Inn where we’re staying, and instead of passing row after row of cars, we pass a much more compact though very densely packed bicycle lot. It’s so full that it’s actually got double-decker racks to handle all of the spectators’ bikes. What a great thing! We’ve got the cheap seats, and I wouldn’t ever want to pay for the more expensive ones. This is where the true action is. From here, you can watch the salmon pink sunset over the mountains that enclose Hiroshima on three sides. The city lights come up, and modern bullet trains come gliding silently to rest in nearby Hiroshima Station.

This is the pep block. There is almost no canned music at a Japanese baseball game. Instead, a bare-bones band leads the rabid fans whenever the Carp are up to bat. Bleating trumpets and pounding drums, elaborate sing-song chants with prescribed movements. The crowd cheers, “Bonzai!” then lapses into a pointed silence when the Tokyo Giants are up to bat. They reel their energy in again, least it accidentally offer encouragement to the other team. This is unrivaled in American sports anywhere; American sporting fans would be ashamed.

This is the pep block. There is almost no canned music at a Japanese baseball game. Instead, a bare-bones band leads the rabid fans whenever the Carp are up to bat. Bleating trumpets and pounding drums, elaborate sing-song chants with prescribed movements. The crowd cheers, “Bonzai!” then lapses into a pointed silence when the Tokyo Giants are up to bat. They reel their energy in again, least it accidentally offer encouragement to the other team. This is unrivaled in American sports anywhere; American sporting fans would be ashamed.

I look around, and Japanese are eating French fries with chopsticks. Others just enjoy a nice bowl of hot soup at the ball park. Beer-vending women carry backpack kegs. I myself sup on Philly cheese steak as interpreted by the Japanese. It is a strip of actual steak on a hard roll drowning in nacho cheese.

Every attendee receives a green sheet of paper with a prayer for world peace printed on it. When John Lennon’s “Imagine” plays over the stadium sound system, the whole crowd waves their green papers high over their heads. This is the eve of the sixty-sixth anniversary of the bombing. That experience and a subsequent commitment to world peace are fundamental to the identity of this city. There is no escaping it. It is inspirational to see so much idealism spring from such negative roots.

The Lantern Ceremony

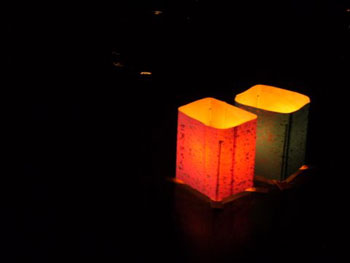

There is a spiritual sense of communion, a union of the intimate and the universal found at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park this evening. The park is the site of the toro nagashi, or lantern ceremony, a traditional Japanese memorial service for the dead. It is by far the most moving part of the day. The skeletal A-Bomb Dome glows bright in the dark, its reflection dancing and shifting shape on the dark surface of the river like some Rorschach test of tragedy, an all-purpose steel and stone reminder of the fragility of even the most durable of man’s accomplishments.

There is a spiritual sense of communion, a union of the intimate and the universal found at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park this evening. The park is the site of the toro nagashi, or lantern ceremony, a traditional Japanese memorial service for the dead. It is by far the most moving part of the day. The skeletal A-Bomb Dome glows bright in the dark, its reflection dancing and shifting shape on the dark surface of the river like some Rorschach test of tragedy, an all-purpose steel and stone reminder of the fragility of even the most durable of man’s accomplishments.

By this light and the light of the primeval moon, people gather to write messages of peace and love on colorful paper, which they proceed to fold into lantern shades. I join several of my new Japanese friends to decorate one, adding the message, “No nations, just people. Peace.” This is written beside the kanji script peace messages of my Japanese friends. This is beautiful, because when you think about it – our grandfathers were trying as hard as they could to kill each other.

We place a lit candle inside our lantern and join thousands of others – Japanese, Americans, Asians, Europeans – on the banks of the Ota River. Lanterns of dozens of colors, the collaborative work of many hands, drift like luminescent souls toward the unknown sea. This communion is profound. Your feet get wet, and you cannot help but feel connected on a spiritual level to what happened here. Suddenly the people who died here are your own people. They are your mothers, fathers, brothers, and sisters.

It is so calm, you can feel every heartbeat in your chest. And if you let yourself, you will almost certainly be moved to tears. My friends and I stake out a spot on the river, and watch the lanterns drifting slowly past our position downstream. We reflect in sparse language on everything we have seen and done these past few days. Hiroshima has the power to chance you. That much is apparent, even if we can’t articulate just what we will carry home from this very special place.

Eventually we find ourselves in Hiroshima’s downtown nightlife district. It’s not very busy for a Saturday night, but that is perfect for our purposes. We’re just looking for a quiet dinner, and we’re rewarded with an intimate little place – shoes off at the door – serving contemporary Japanese cuisine and the best sake I have ever tasted.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and Miyajima Island Tour from Hiroshima

If You Go:

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park is easily accessible from the Hiroden Genbaku Dome-mae Station, a clearly labeled stop on the extensive Hiroshima street car system. The Lantern Ceremony takes place only once a year on August 6, the anniversary of the atomic bombing, but it’s well worth your effort to plan your visit to coincide with this beautiful service.

The Hiroshima Carp play in the beautiful Mazda Zoom Zoom Stadium which is an easy ten minute walk from central Hiroshima Station, the main JR West and Shinkansen terminal for the whole city. Tickets are often available right up to game time.

About the author:

Thomas Kenning decided to leave his life as a high school history teacher in order to do crazier things. One of those crazy things was traveling to Japan to study the legacy of the atomic bombs. He’s written about this and other foolhardy experiences in zines and on his blog at cattywampus.tumblr.com.

Photo credits:

Itsukushima Shinto shrine at Miyajima island, near Hiroshima photo by Nicki Eliza Schinow on Unsplash

All other photos are by Thomas Kenning.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.