by Elizabeth von Pier

Marrakech was our first stop in Morocco. Founded in 1062 and known as the “ochre city” for the color of the buildings and walls in the old Arab section, we entered the city on wide boulevards teeming with traffic, chain hotels, modern white stucco buildings and palm trees. I felt disappointed; we could have been somewhere in Florida. But then we passed through the old city walls and a park where camels were sitting in a shady grove. People strolled the streets wearing their traditional jellabiyas and “calls to prayer” were coming from loudspeakers on the minarets of the mosques. This was Morocco!

We were staying in a riad, and this one turned out to be a destination in itself. A “riad” is a traditional Moroccan house, located within the ancient medina and designed around a central courtyard, pool or fountain, and garden. The owners had purchased several adjoining houses and combined them so that there are two courtyards and 26 guest rooms, several sitting rooms, two restaurants, a jazz bar, and a spa. The hotelier gave us a tour and showed us to a lovely room which faced the pool and inner courtyard. As I stood on the balcony, I looked out over rooftops of the old city and a minaret a short distance away. Down below was a pool, trees, potted plants, tables covered with white tablecloths, pierced pendant lanterns, and lovely tile work. Each morning at dawn, we were awakened to the “call to prayer” from the mosque. A traditional afternoon tea is offered in the courtyard each day, and we enjoyed typically Moroccan mint tea served with an assortment of tiny cookies. It felt like something out of “Arabian Nights”.

We were staying in a riad, and this one turned out to be a destination in itself. A “riad” is a traditional Moroccan house, located within the ancient medina and designed around a central courtyard, pool or fountain, and garden. The owners had purchased several adjoining houses and combined them so that there are two courtyards and 26 guest rooms, several sitting rooms, two restaurants, a jazz bar, and a spa. The hotelier gave us a tour and showed us to a lovely room which faced the pool and inner courtyard. As I stood on the balcony, I looked out over rooftops of the old city and a minaret a short distance away. Down below was a pool, trees, potted plants, tables covered with white tablecloths, pierced pendant lanterns, and lovely tile work. Each morning at dawn, we were awakened to the “call to prayer” from the mosque. A traditional afternoon tea is offered in the courtyard each day, and we enjoyed typically Moroccan mint tea served with an assortment of tiny cookies. It felt like something out of “Arabian Nights”.

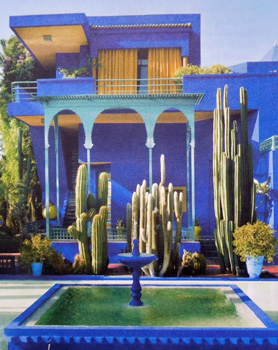

Within walking distance of the riad is the Majorelle Garden, a botanical and landscape garden that was created in the 1920’s by French painter Jacques Majorelle. It is a fantastical delight and beautiful to behold. Special shades of bold cobalt blue are used in the gardens and on the buildings, walkways and pergolas, and are a stunning accent to the greens of the cacti, palm trees, bamboo, bougainvilleas, and ferns. Neglected after the painter’s death in 1962, the property was later restored by fashion designer Yves Saint-Laurent who bought the garden and used it as his residence. After he died in 2008, his ashes were scattered in the garden and a memorial was built in his honor.

Within walking distance of the riad is the Majorelle Garden, a botanical and landscape garden that was created in the 1920’s by French painter Jacques Majorelle. It is a fantastical delight and beautiful to behold. Special shades of bold cobalt blue are used in the gardens and on the buildings, walkways and pergolas, and are a stunning accent to the greens of the cacti, palm trees, bamboo, bougainvilleas, and ferns. Neglected after the painter’s death in 1962, the property was later restored by fashion designer Yves Saint-Laurent who bought the garden and used it as his residence. After he died in 2008, his ashes were scattered in the garden and a memorial was built in his honor.

The “souk” is the commercial quarter of the medina and we went there to experience the activity and to bargain for some souvenirs. Colorful stalls line the alleyways, selling everything from carpets to clothing, scarves, jewelry, leather products, olives and housewares. We were on a quest to find a decorative tagine like the ones used on our riad’s breakfast buffet for fruits, nuts and pastries. Mohammed patiently took us from stall to stall until my sister finally found one to bring back home with her. There are no set prices in the souk so she had to use her bargaining skills. It can get rather tense as the seller dramatically tells the buyer that she is “killing” him with the low price she is offering. But in the end, she prevailed and took home a beautiful tagine to use for entertaining in the Moroccan style.

The “souk” is the commercial quarter of the medina and we went there to experience the activity and to bargain for some souvenirs. Colorful stalls line the alleyways, selling everything from carpets to clothing, scarves, jewelry, leather products, olives and housewares. We were on a quest to find a decorative tagine like the ones used on our riad’s breakfast buffet for fruits, nuts and pastries. Mohammed patiently took us from stall to stall until my sister finally found one to bring back home with her. There are no set prices in the souk so she had to use her bargaining skills. It can get rather tense as the seller dramatically tells the buyer that she is “killing” him with the low price she is offering. But in the end, she prevailed and took home a beautiful tagine to use for entertaining in the Moroccan style.

We expected to engage in this type of buying and selling process in the souk. But we did not expect the tactics used on the street to capture the attention of the unsuspecting tourist. Men posing as workers in our riad who had the day off said they recognized us from the riad and shared important information about a special shop a couple of streets away. A co-conspirator “happened” to overhear the conversation and offered to show us the way. We started to follow, but then thought better of it. A sign on the wall in the riad warned about these tactics, but we had not noticed it. And to think we almost fell for it! We probably won’t see these “actors” on the big screen anytime soon, but their performance and timing was so well executed that I feel they deserve every dirham of their commissions.

There also was an interesting specialty shop in the souk where three Berber women were laboriously extracting oil from the nuts of the argan tree to make food products and cosmetics. Argan trees are endemic to Morocco and the oil that is extracted is very precious and has many health benefits. A salesman let us sample some of their special products, and we filled our baskets with gifts for people back home. There was no bargaining here because supposedly this is the only place where the skin products are pure and the oils used for cooking are not diluted.

There also was an interesting specialty shop in the souk where three Berber women were laboriously extracting oil from the nuts of the argan tree to make food products and cosmetics. Argan trees are endemic to Morocco and the oil that is extracted is very precious and has many health benefits. A salesman let us sample some of their special products, and we filled our baskets with gifts for people back home. There was no bargaining here because supposedly this is the only place where the skin products are pure and the oils used for cooking are not diluted.

Leaving the souk, we entered the beating heart of the city, Place Jemaa El Fna, which dates from the 12th century and was designated a UNESCO world heritage site in 2001. This is a large square inside the walled city, lined with restaurants and shops and the setting for performances by snake charmers, musicians, storytellers, fortune-tellers, henna artists, monkey performers, acrobats, and transvestite dancers. It indeed is an assortment of fantastic sights and smells of Moroccan folklore. One photo here will cost you ten dirham.

The Koutoubia Mosque with its 254 foot high minaret is a landmark and symbol of the city. We were just outside the mosque when the “call to prayer” came from the loudspeakers above. Not far away is the Bahia Palace, a masterpiece of Moroccan architecture with its brilliant mosaics, carved woodwork and gorgeous marbles. Like most Arab palaces, it contains charming and tranquil gardens, beautiful patios and rooms richly decorated with tiles. And we visited the tombs of the Saâdi rulers which date back to the 16th century but were only discovered and restored around 1917. These tombs shelter the bodies of about 60 Saadian sultans and their families and are an outstanding example of Moorish tilework and art.

The Koutoubia Mosque with its 254 foot high minaret is a landmark and symbol of the city. We were just outside the mosque when the “call to prayer” came from the loudspeakers above. Not far away is the Bahia Palace, a masterpiece of Moroccan architecture with its brilliant mosaics, carved woodwork and gorgeous marbles. Like most Arab palaces, it contains charming and tranquil gardens, beautiful patios and rooms richly decorated with tiles. And we visited the tombs of the Saâdi rulers which date back to the 16th century but were only discovered and restored around 1917. These tombs shelter the bodies of about 60 Saadian sultans and their families and are an outstanding example of Moorish tilework and art.

Leaving Marrakech two days later, we transferred to a four-wheel drive vehicle for our trip over the High Atlas Mountains via the Tizin Tichka Pass. Our destination was Ouarzazate, five hours away. Mohammed expertly navigated the vehicle around hairpin turns and over narrow roads that came within inches of steep drop-offs into canyons below. Besides the scenery, the sights we saw along the way are memorable. Donkeys loaded with meat, produce and wheat were led by jellabiya-clad men to village markets high in these mountains. We passed caves used by the Bedouins, nomadic tribes who live mainly in the desert but use the caves when crossing the mountains on their camels. We caught a glimpse of a road worker pausing for prayer on an outcrop of the mountain. And we saw stork nests, shepherds tending their flocks, and tiny villages made out of sandstone and hay that blend into the color of the hillsides on which they are built. No matter how small the village, there’s always a mosque with its minaret towering above everything.

Ouarzazate, nicknamed “the door of the (Sahara) Desert”, was built as a garrison and administrative center by the French, but today it serves as the Hollywood of the Kingdom. This is where “Lawrence of Arabia”, “Jesus of Nazareth”, “Gladiator”, “Indiana Jones” and many other films were made. While it is in a lovely setting, the town itself is somewhat tacky. There are several movie studios that you can tour and new housing developments are springing up in the otherwise beautiful landscape.

Ouarzazate, nicknamed “the door of the (Sahara) Desert”, was built as a garrison and administrative center by the French, but today it serves as the Hollywood of the Kingdom. This is where “Lawrence of Arabia”, “Jesus of Nazareth”, “Gladiator”, “Indiana Jones” and many other films were made. While it is in a lovely setting, the town itself is somewhat tacky. There are several movie studios that you can tour and new housing developments are springing up in the otherwise beautiful landscape.

There are some interesting and beautiful casbahs nearby that have also been the setting for movies. Mohammed led us through the old rooms of the Kasbah de Taourirt and the alleyways of the more famous Ait Benhaddou, both sandstone in color and very picturesque. They show how tribes lived and protected themselves in former times. The pathways into Ait Benhaddou are filled with shops and artisans working at their crafts. A woman sitting on her stoop invited us to see her home. She showed us her “old” kitchen with its bee-hive oven, her “modern” kitchen with its fifties-style sink and tile backsplash, and a small room open to the sky where the sheep were housed in very tight quarters. The living room was full of carpets that she supposedly made herself and would sell for a good price. So the tip we gave her was really for the privilege of visiting her shop. Fooled again!

Leaving casbah Ait Benhaddou, we drove for miles through the foothills of the mountains and the rolling sand hills of the desert and started to wonder where we could possibly be staying for the night. Hopefully not in a Bedouin tent! But when we finally came upon our riad, we drove through a large sandstone arch and entered a typical Moroccan courtyard, set in an oasis with palm trees and beautiful plantings around a central pool and fountain. You’d never expect to find a place like this here in such a remote location. But it does make sense—a Frenchman opened it to cater to the movie industry.

Leaving casbah Ait Benhaddou, we drove for miles through the foothills of the mountains and the rolling sand hills of the desert and started to wonder where we could possibly be staying for the night. Hopefully not in a Bedouin tent! But when we finally came upon our riad, we drove through a large sandstone arch and entered a typical Moroccan courtyard, set in an oasis with palm trees and beautiful plantings around a central pool and fountain. You’d never expect to find a place like this here in such a remote location. But it does make sense—a Frenchman opened it to cater to the movie industry.

In order to get to Casablanca, our next and final destination, we had to drive back over the High Atlas Mountains. Casablanca is very busy and teeming with traffic but it has a beautiful new mosque. Hassan II is one of the world’s largest and it was built over six years from “contributions” made by every family in in the city. We also drove by and took photos of Rick’s Café made famous by the film “Casablanca”, and toured the medina with its maze-like streets that are almost impossible to navigate in a car. Everywhere in Casablanca, the driving was terrifying, partly because people play “chicken” as they maneuver in and out of traffic. Unfortunately for us, Mohammed was very good at playing “chicken”.

The Islamic month of Ramadan had just started and Mohammed had fasted all that day as we made the long journey from Ouarzazate. Ramadan is a time of spiritual reflection and increased devotion and worship which is observed as a month of fasting from sunrise to sunset. So early that evening, we arrived at the hotel very hungry after the long drive and had to wait until the sun set for food to be served. We were the first ones in the restaurant when the sun hit the horizon!

If You Go:

♦ Riad in Marrakech, La Maison Arabe in the Medina

♦ Riad in Ouarzazate, Riad Ksar Ighnda

♦ Hotel in Casablanca, Sofitel Tour Blanche

About the author:

Elizabeth von Pier is a retired banker and photojournalist who travels extensively throughout the world. In her retirement, she has written and published articles in travelmag.co.uk, WAVE Journey, Travel Thru History and hackwriters.com. Ms. von Pier lives in Hingham, Massachusetts.

First photo by danyloz2002 from Pixabay

All other photos are by Elizbeth von Pier:

Minaret

Majorelle Garden

Tannery worker

Tagines

Women extracting argan oil

Snake charmers in Place Jemaa El Fna

Village in High Atlas Mountains

Movie studio

“Balak!”

“Balak!” We amble down Talaa Kebira, one of the medina’s principal roadways, and soon come to Bou Inania Medersa. This is the most awe-inspiring Koranic school in Fes, and one of the few open to the public. Every room has lofty, sumptuously detailed ceilings with carved cedar beams and stunning onyx marble floors. The walls are covered with handcrafted tiles adorned with dazzling gold and turquoise geometric motifs. Intricate lime-coloured geometrical designs are also on display in the courtyard, where the 14th Century fountain still gushes today. In a corner an imam, a priest, kneels and chants verses from the Koran.

We amble down Talaa Kebira, one of the medina’s principal roadways, and soon come to Bou Inania Medersa. This is the most awe-inspiring Koranic school in Fes, and one of the few open to the public. Every room has lofty, sumptuously detailed ceilings with carved cedar beams and stunning onyx marble floors. The walls are covered with handcrafted tiles adorned with dazzling gold and turquoise geometric motifs. Intricate lime-coloured geometrical designs are also on display in the courtyard, where the 14th Century fountain still gushes today. In a corner an imam, a priest, kneels and chants verses from the Koran.

As we descend further into the bowels of the medina, our guide urges us to stay close together. She doesn’t have to tell me twice. I would love nothing better than to wander the zigzag of avenues on my own, but finding my way out would be nothing short of a miracle. I’m told that even the best maps are unreliable. The streets are swarming with humanity today; the thrum of voices is omnipresent. Since none of the roads are wide enough for cars to navigate, donkey carts and scooters are the accepted modes of transport, making this the world’s largest urban car-free zone.

As we descend further into the bowels of the medina, our guide urges us to stay close together. She doesn’t have to tell me twice. I would love nothing better than to wander the zigzag of avenues on my own, but finding my way out would be nothing short of a miracle. I’m told that even the best maps are unreliable. The streets are swarming with humanity today; the thrum of voices is omnipresent. Since none of the roads are wide enough for cars to navigate, donkey carts and scooters are the accepted modes of transport, making this the world’s largest urban car-free zone. From the Souk Attarine our odyssey continues. Blind alleys that seem to lead nowhere open onto swarming fundouks with gurgling fountains. We pass countless vendors that hawk candles, wood carvings, jewelry, and fresh herbs from shops hardly bigger than a closet. A posse of young boys plays a boisterous game of soccer with two rocks serving as goalposts. The frenetic energy of it all is exhilarating.

From the Souk Attarine our odyssey continues. Blind alleys that seem to lead nowhere open onto swarming fundouks with gurgling fountains. We pass countless vendors that hawk candles, wood carvings, jewelry, and fresh herbs from shops hardly bigger than a closet. A posse of young boys plays a boisterous game of soccer with two rocks serving as goalposts. The frenetic energy of it all is exhilarating.

There is one last stop on our schedule, and we don’t need a map to find it. The rank stench of the open air leather tanneries serves as a guidepost to one of Fes’ most famous attractions. We’re led up a staircase to a leather shop that opens onto a terrace where we view the tanneries below.

There is one last stop on our schedule, and we don’t need a map to find it. The rank stench of the open air leather tanneries serves as a guidepost to one of Fes’ most famous attractions. We’re led up a staircase to a leather shop that opens onto a terrace where we view the tanneries below. We’re seated on plush cushions around hand-carved wooden hexagon-shaped tables. The high ceiling is covered in gorgeous inlaid wood painted in shades of emerald, burgundy, and cobalt. It feels like we’re dining in someone’s home, and with good reason. A couple of years ago owners Fouad and Karima turned their sitting room and courtyard into a restaurant. They don’t have a liquor license, but they have no objections when we bring out cheap bottles of Moroccan wine that we bought at the supermarket.

We’re seated on plush cushions around hand-carved wooden hexagon-shaped tables. The high ceiling is covered in gorgeous inlaid wood painted in shades of emerald, burgundy, and cobalt. It feels like we’re dining in someone’s home, and with good reason. A couple of years ago owners Fouad and Karima turned their sitting room and courtyard into a restaurant. They don’t have a liquor license, but they have no objections when we bring out cheap bottles of Moroccan wine that we bought at the supermarket.

I was delighted to wake up the next morning to a clear view of the Rock of Gibraltar from my window and knowing that I would be spending the day in Morocco. Arriving at the Port of Algeciras just 100 feet across the hotel, I was instructed to wait for my guide as soon as I off-boarded the ferry in Ceuta. Ceuta is one of the two Spanish autonomous communities in North Africa along with Melilla located about 390 further east. Ferries also depart to Melilla on the northern coast of Africa from the ports of Malaga or Almeria that can take over 9 hours across the Alborán Sea.

I was delighted to wake up the next morning to a clear view of the Rock of Gibraltar from my window and knowing that I would be spending the day in Morocco. Arriving at the Port of Algeciras just 100 feet across the hotel, I was instructed to wait for my guide as soon as I off-boarded the ferry in Ceuta. Ceuta is one of the two Spanish autonomous communities in North Africa along with Melilla located about 390 further east. Ferries also depart to Melilla on the northern coast of Africa from the ports of Malaga or Almeria that can take over 9 hours across the Alborán Sea.

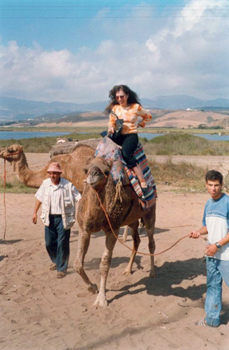

I looked at one of the passengers with a puzzled look that was immediately reciprocated. Moments later the mini bus suddenly pulled off to the side of the road where locals were offering camel rides for one Euro. At first I hesitated, but it took just six words from one of the couples to get me on top of that camel, “You’ll regret it if you don’t!”

I looked at one of the passengers with a puzzled look that was immediately reciprocated. Moments later the mini bus suddenly pulled off to the side of the road where locals were offering camel rides for one Euro. At first I hesitated, but it took just six words from one of the couples to get me on top of that camel, “You’ll regret it if you don’t!” After passing through the chaos of the open air food market, we arrived at the fabric and textile market. On display were hundreds of thick fabrics of the most vivid colors for sale hand woven by local Berber women. Lost in my world I was when suddenly one such woman stopped me and grabbed me by my shoulders.

After passing through the chaos of the open air food market, we arrived at the fabric and textile market. On display were hundreds of thick fabrics of the most vivid colors for sale hand woven by local Berber women. Lost in my world I was when suddenly one such woman stopped me and grabbed me by my shoulders. The next stop was the carpet demonstration. Here, we were led into a showroom where traditional mint tea was offered while we waited for the ‘show’ to begin. One by one, they rolled out these works of art, each more exquisite and intricate than the last. By the time the demonstration was over, the prices were greatly reduced. No-one in our group had any intention of purchasing a rug yet the vendor instructed us to individually say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to every single carpet that they had rolled out. After these very uncomfortable minutes were over, we quickly departed leaving the disgruntled vendors mumbling to themselves while they hastily rolled back the carpets.

The next stop was the carpet demonstration. Here, we were led into a showroom where traditional mint tea was offered while we waited for the ‘show’ to begin. One by one, they rolled out these works of art, each more exquisite and intricate than the last. By the time the demonstration was over, the prices were greatly reduced. No-one in our group had any intention of purchasing a rug yet the vendor instructed us to individually say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to every single carpet that they had rolled out. After these very uncomfortable minutes were over, we quickly departed leaving the disgruntled vendors mumbling to themselves while they hastily rolled back the carpets. We were now on our way to the spice and pharmacy market; a welcomed relief as the ‘pharmacist’ dressed in a white lab coat was quite the comedian. The small room resembled a medieval apothecary with all sorts of jars and containers of all colors, shapes, and sizes filled with oils, fragrances, creams, herbal remedies, spices, and teas that cured everything from anxiety to hangovers. The pharmacist/comedian demonstrated the wonders of the selected products that we smelled, rubbed on our skin, or whatever we were instructed to do. Each of us bought a few cosmetic and medicinal items as we did not want to offend this vendor as well.

We were now on our way to the spice and pharmacy market; a welcomed relief as the ‘pharmacist’ dressed in a white lab coat was quite the comedian. The small room resembled a medieval apothecary with all sorts of jars and containers of all colors, shapes, and sizes filled with oils, fragrances, creams, herbal remedies, spices, and teas that cured everything from anxiety to hangovers. The pharmacist/comedian demonstrated the wonders of the selected products that we smelled, rubbed on our skin, or whatever we were instructed to do. Each of us bought a few cosmetic and medicinal items as we did not want to offend this vendor as well. Next on our busy itinerary was a one hour bus ride to Tangier, the “Gateway to Africa” founded in the 5th century BCE. I was especially excited as it was here where my grandparents worked, met and married nearly a century ago. Upon arrival, Mohammed took us through another quick walk through the zigzag alleys and corners of the medina to the Mamounia Palace Restaurant. The restaurant, filled to capacity with other tour groups, was lavishly decorated with crimson and golden tapestries, deep red tablecloths, and plush sofas. I immediately took a photo of the lovely view from the balcony window.

Next on our busy itinerary was a one hour bus ride to Tangier, the “Gateway to Africa” founded in the 5th century BCE. I was especially excited as it was here where my grandparents worked, met and married nearly a century ago. Upon arrival, Mohammed took us through another quick walk through the zigzag alleys and corners of the medina to the Mamounia Palace Restaurant. The restaurant, filled to capacity with other tour groups, was lavishly decorated with crimson and golden tapestries, deep red tablecloths, and plush sofas. I immediately took a photo of the lovely view from the balcony window. We each took turns posing with the musicians for a small fee and the quartet began to play traditional Moroccan music with such instruments as the hand drum (darbuka), lute (oud), tambourine (riq), and violin (rababa). Moments later, our lunch was served consisting of lentil soup, a briouat or meat-filled pastry, hummus and bread, chicken with couscous and vegetables, followed by a slice of melon with mint tea for dessert. Halfway through the meal, a blonde belly dancer in a purple and gold costume whirled her way into the center of the room and entertained us to the lively music of the band.

We each took turns posing with the musicians for a small fee and the quartet began to play traditional Moroccan music with such instruments as the hand drum (darbuka), lute (oud), tambourine (riq), and violin (rababa). Moments later, our lunch was served consisting of lentil soup, a briouat or meat-filled pastry, hummus and bread, chicken with couscous and vegetables, followed by a slice of melon with mint tea for dessert. Halfway through the meal, a blonde belly dancer in a purple and gold costume whirled her way into the center of the room and entertained us to the lively music of the band. Shortly after our lunch, were once again whisked to the bus and into a department-sized store in the center of Tangier selling the finest Moroccan handicrafts, gifts, furnishings, rugs, leather goods, pottery, clothing, jewelry, and quality souvenirs available. We were told that we had a half hour to shop and encouraged to purchase as much as we could. This would be the last stop on our itinerary and right on schedule, after 30 minutes, we made our way back to the bus.

Shortly after our lunch, were once again whisked to the bus and into a department-sized store in the center of Tangier selling the finest Moroccan handicrafts, gifts, furnishings, rugs, leather goods, pottery, clothing, jewelry, and quality souvenirs available. We were told that we had a half hour to shop and encouraged to purchase as much as we could. This would be the last stop on our itinerary and right on schedule, after 30 minutes, we made our way back to the bus.

Some people will try to tell you that this is not Africa. Morocco, located on the continent’s northwestern edge, is something of an enigma in this regard. Its people are mostly descended from Arab invaders and indigenous Berbers, whose DNA and culture are closer to that of Mediterranean Europe than anything below the Sahara. But when the Gnaoua World Music Festival kicks off every June in Essaouira, on Morocco’s Atlantic coast, its African heart emerges – beating strongly to the rhythms of the drums and three-string basses of the West African slaves who arrived here centuries ago.

Some people will try to tell you that this is not Africa. Morocco, located on the continent’s northwestern edge, is something of an enigma in this regard. Its people are mostly descended from Arab invaders and indigenous Berbers, whose DNA and culture are closer to that of Mediterranean Europe than anything below the Sahara. But when the Gnaoua World Music Festival kicks off every June in Essaouira, on Morocco’s Atlantic coast, its African heart emerges – beating strongly to the rhythms of the drums and three-string basses of the West African slaves who arrived here centuries ago. Gnaoua music is alive and well in Morocco today, though its spiritual origins have been somewhat lost through its own popularity. It’s not just the Sufis who perform Gnaoua music anymore. It’s played in clubs by fusion bands, and on world tours by famous musicians interested in cross-cultural connections. But most significantly, it has become the centerpiece of one of Morocco’s biggest festivals, a four-day event that takes place at the beginning of every summer.

Gnaoua music is alive and well in Morocco today, though its spiritual origins have been somewhat lost through its own popularity. It’s not just the Sufis who perform Gnaoua music anymore. It’s played in clubs by fusion bands, and on world tours by famous musicians interested in cross-cultural connections. But most significantly, it has become the centerpiece of one of Morocco’s biggest festivals, a four-day event that takes place at the beginning of every summer. Some call it the Woodstock of Africa, while others claim it has become too corporate. Founded seventeen years ago, the Gnaoua World Music Festival (known officially by its French name, Le Festival Gnaoua et des musiques du Monde d’Essaouira) attracts over 300,000 people, who not only come to hear Gnaoua music, but also sounds from all over Africa. A lot of the crowd is European, not just hippie-types but also music enthusiasts, wind surfers, and those on cheap breaks. But there are a lot of Moroccans here too, who can afford to come because most of the concerts are free, running late into the night on the town’s beaches.

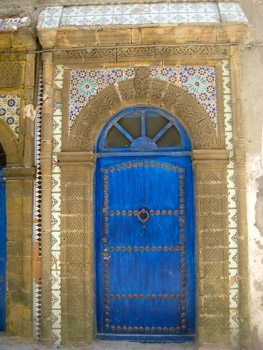

Some call it the Woodstock of Africa, while others claim it has become too corporate. Founded seventeen years ago, the Gnaoua World Music Festival (known officially by its French name, Le Festival Gnaoua et des musiques du Monde d’Essaouira) attracts over 300,000 people, who not only come to hear Gnaoua music, but also sounds from all over Africa. A lot of the crowd is European, not just hippie-types but also music enthusiasts, wind surfers, and those on cheap breaks. But there are a lot of Moroccans here too, who can afford to come because most of the concerts are free, running late into the night on the town’s beaches. Essaouira is known as the windy city, though it bears other names too: the Portuguese, who laid the foundations for the town we see today, called it Mogador, and its Berber name simply means “the wall”. It’s a fortified city with walls that keep out the wind, and also much of modernity. The medina at its centre is labyrinthine and painted almost entirely in white and blue. Gnaoua music permeates the streets, even outside of festival time, and other hallmarks of Moroccan life are there too: traditional hammams (spas), markets, a souk devoted entirely to wood artisans, an old Jewish synagogue (a reminder that Essaouira was once 40% Jewish) and cafés that serve simple, yet delicious fare (always, of course, accompanied by mint tea). These are the best places to eat, especially if you’re on a budget and want to nosh like the locals. Bowls of lentils, spiced with cumin, paprika, and laced with meat, can be bought for as little as 6 dirhams (around 75 cents), and are served with bread, for free. White beans are a similarly delicious bargain, though if you’re feeling a bit more luxurious, fish is the best thing to eat in Essaouira. Kefta, traditional Moroccan meatballs, stuffed with onions and parsley, are delectable too, but sardines, bought fresh from the fishermen down by the beach are even better. Once bought, you can take the fish to a restaurant to be cooked on the spot, often with traditional chermoula sauce (a mixture of cilantro, parsley, chili, lemon, olive oil and spices).

Essaouira is known as the windy city, though it bears other names too: the Portuguese, who laid the foundations for the town we see today, called it Mogador, and its Berber name simply means “the wall”. It’s a fortified city with walls that keep out the wind, and also much of modernity. The medina at its centre is labyrinthine and painted almost entirely in white and blue. Gnaoua music permeates the streets, even outside of festival time, and other hallmarks of Moroccan life are there too: traditional hammams (spas), markets, a souk devoted entirely to wood artisans, an old Jewish synagogue (a reminder that Essaouira was once 40% Jewish) and cafés that serve simple, yet delicious fare (always, of course, accompanied by mint tea). These are the best places to eat, especially if you’re on a budget and want to nosh like the locals. Bowls of lentils, spiced with cumin, paprika, and laced with meat, can be bought for as little as 6 dirhams (around 75 cents), and are served with bread, for free. White beans are a similarly delicious bargain, though if you’re feeling a bit more luxurious, fish is the best thing to eat in Essaouira. Kefta, traditional Moroccan meatballs, stuffed with onions and parsley, are delectable too, but sardines, bought fresh from the fishermen down by the beach are even better. Once bought, you can take the fish to a restaurant to be cooked on the spot, often with traditional chermoula sauce (a mixture of cilantro, parsley, chili, lemon, olive oil and spices). In festival time, the concerts mostly take place on the beaches, but also spill out into the clubs of the new city, located outside the old medina walls. There are events for every taste, though the biggest, most exciting shows happen outdoors on the free stages. Music runs pretty much all night, which not only creates a 24/7 party atmosphere, but also provides a welcome relief to the mid-day temperatures of the Moroccan summer. Essaouira is less hot than Marrakech, thanks to ocean breezes, but high noon temperatures are still nothing to laugh at. The nighttime is cool, perfect weather for dancing to the beats of the Sufi Brotherhoods or visiting world musicians. And dance you will. This is Africa, remember, albeit a much less traditional, more open-minded version of the continent than you might experience elsewhere. Vendors circulate throughout the concert space, selling donuts and other tasty treats. More savory fare can be bought from makeshift stands on the perimeter, selling corn, fish, hard boiled eggs with cumin and salt, and pastries. Alcohol is not obviously easy to procure, but despite what the hustlers might try to tell you (searching for a commission), there are several liquor depots in the new city where you can buy alcohol at a fixed price. It’s very common to see both tourists and locals imbibing on the beach, though usually out of water bottles, often containing the local firewater.

In festival time, the concerts mostly take place on the beaches, but also spill out into the clubs of the new city, located outside the old medina walls. There are events for every taste, though the biggest, most exciting shows happen outdoors on the free stages. Music runs pretty much all night, which not only creates a 24/7 party atmosphere, but also provides a welcome relief to the mid-day temperatures of the Moroccan summer. Essaouira is less hot than Marrakech, thanks to ocean breezes, but high noon temperatures are still nothing to laugh at. The nighttime is cool, perfect weather for dancing to the beats of the Sufi Brotherhoods or visiting world musicians. And dance you will. This is Africa, remember, albeit a much less traditional, more open-minded version of the continent than you might experience elsewhere. Vendors circulate throughout the concert space, selling donuts and other tasty treats. More savory fare can be bought from makeshift stands on the perimeter, selling corn, fish, hard boiled eggs with cumin and salt, and pastries. Alcohol is not obviously easy to procure, but despite what the hustlers might try to tell you (searching for a commission), there are several liquor depots in the new city where you can buy alcohol at a fixed price. It’s very common to see both tourists and locals imbibing on the beach, though usually out of water bottles, often containing the local firewater. The festival atmosphere pervades the city, and not just at night on the beaches by the big music stages. It’s on the streets in the daytime too, in the official processions of the Gnaoua musicians, and in the unofficial parades of young Moroccan rastas, Spanish girls in harem pants, the old Djellaba-clad (a traditional Moroccan robe) hooked-nose man who haunts the medina and claims to have worked for Cat Stevens, and in the gentle giant dancing manically to the beat of his own drummer. In fact, the festival atmosphere begins the moment you step on the bus to Essaouira. Buses run regularly between Marrakech and the port, and tickets can be bought either directly from the ticket office inside the bus station, or from hustlers outside, who may or may not offer you a better price, albeit probably on a worse bus. But a lower class bus is not a guarantee of a bad experience. In fact, you’re more likely to meet locals that way, locals who, unlike many people you meet on the street, will give you advice for free. Some might recommend a place to stay or eat salty grilled fish, while others will try to convince you of their love for Bob Marley, or may even offer you hashish or wine mixed with cola – both of which maintain various levels of illegality for Moroccans, though each proliferate at the festival. But for most attendees, the music on its own is transcendent enough: beautiful and ancient as it floats above the storied corners of the medina, past the spice sellers and fishing boats, and out to sea.

The festival atmosphere pervades the city, and not just at night on the beaches by the big music stages. It’s on the streets in the daytime too, in the official processions of the Gnaoua musicians, and in the unofficial parades of young Moroccan rastas, Spanish girls in harem pants, the old Djellaba-clad (a traditional Moroccan robe) hooked-nose man who haunts the medina and claims to have worked for Cat Stevens, and in the gentle giant dancing manically to the beat of his own drummer. In fact, the festival atmosphere begins the moment you step on the bus to Essaouira. Buses run regularly between Marrakech and the port, and tickets can be bought either directly from the ticket office inside the bus station, or from hustlers outside, who may or may not offer you a better price, albeit probably on a worse bus. But a lower class bus is not a guarantee of a bad experience. In fact, you’re more likely to meet locals that way, locals who, unlike many people you meet on the street, will give you advice for free. Some might recommend a place to stay or eat salty grilled fish, while others will try to convince you of their love for Bob Marley, or may even offer you hashish or wine mixed with cola – both of which maintain various levels of illegality for Moroccans, though each proliferate at the festival. But for most attendees, the music on its own is transcendent enough: beautiful and ancient as it floats above the storied corners of the medina, past the spice sellers and fishing boats, and out to sea.

The present city with its much admired walls and Medina is a creation, a purpose built sea port, commissioned by King Mohammed III during the 18th century. He wanted to develop trade with Europe and beyond and to establish a counterbalance to Agadir, whose inhabitants favored a rival of him. For twelve years, the king instructed and oversaw French engineer and architect Theodore Cornut, who designed the modern city, the medina and the international quarters. At the time, Morocco depended heavily on the caravan trade, which brought merchandise from sub-Saharan Africa to Timbuktu, then from there through the desert and over the Atlas mountains to Marrakesh and, finally, making use of the straight road, to the thriving port of Essaouira.

The present city with its much admired walls and Medina is a creation, a purpose built sea port, commissioned by King Mohammed III during the 18th century. He wanted to develop trade with Europe and beyond and to establish a counterbalance to Agadir, whose inhabitants favored a rival of him. For twelve years, the king instructed and oversaw French engineer and architect Theodore Cornut, who designed the modern city, the medina and the international quarters. At the time, Morocco depended heavily on the caravan trade, which brought merchandise from sub-Saharan Africa to Timbuktu, then from there through the desert and over the Atlas mountains to Marrakesh and, finally, making use of the straight road, to the thriving port of Essaouira.

The long stretched island of Mogador protects Essaouira from the strongest Atlantic winds, but there is still plenty around to make the place a paradise for surfers and kite surfers. The wide, white beaches invite to sunbathing, swimming and any other imaginable kind of water sport.

The long stretched island of Mogador protects Essaouira from the strongest Atlantic winds, but there is still plenty around to make the place a paradise for surfers and kite surfers. The wide, white beaches invite to sunbathing, swimming and any other imaginable kind of water sport. Small wonder that this picturesque, sedate and slightly melancholic city attracted such divers personalities as Churchill, Welles and Hendrix. Orson Welles even got honored with a statue, although his nose is now missing.

Small wonder that this picturesque, sedate and slightly melancholic city attracted such divers personalities as Churchill, Welles and Hendrix. Orson Welles even got honored with a statue, although his nose is now missing.