by Renee Hefti Graham

Chitwan, a hunting resort for royal families in the 1800s, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984. Covering 360 sq. miles in south west Nepal, the National Park is considered one of the finest wildlife sanctuaries in Asia.

My travel package included a return bus ticket, 3 nights accommodation, meals, a jeep ride and other daily activities. Despite being only 90 miles from Kathmandu, the bus trip takes 6 – 7 hours but could take more than 12.

Waiting to board, I shouldn’t have looked at the tires. They were bald, but this was Nepal. Had I seen any vehicles with tread? I tried not to think of the tires as our driver pushed his way into typical morning chaos. Through belching exhaust, constant honking and yelling, we jockeyed with other buses, (piled high with luggage) and open back trucks, (jammed with people or crates of pigs and chickens). Overloaded cars, taxis, motorcycles and bicycles, darted in and out, barely slowing for meandering cows.

Past Thamel, the entertainment center of Nepal, the road to Chitwan narrowed, was winding and bumpy with pot holes and broken pavement. Sensing I was in for quite a ride, I swallowed a couple of Advil.

Supposedly, a two lane road, but in Nepali style, there were no painted lines. When there was a momentary break in oncoming traffic, drivers, (including ours), headed to the empty spot, sharply cutting back only when a head-on was imminent. I decided to stop looking out the front of the bus.

Supposedly, a two lane road, but in Nepali style, there were no painted lines. When there was a momentary break in oncoming traffic, drivers, (including ours), headed to the empty spot, sharply cutting back only when a head-on was imminent. I decided to stop looking out the front of the bus.

Watching through the side window, the scenery was spectacular: rivers, forests, lush green fields, planted terraces, shacks, farmers, herders and their goats. But when the oncoming lane was plugged with traffic, buses and heavily loaded trucks passed on the right. Passing on the right with its loose gravel and steep cliffs was suicidal. Glancing down into ravines was like looking at a twisted metal cemetery.

Occasionally we moved along fairly quickly. When there was a traffic jam, hordes of villagers, from who knows where, arrived with loaded baskets of bananas and trinkets. They banged on bus windows, hoping for a sale.

Arriving in Chitwan eight hours later, was a relief. The lodge, surrounded by rice paddies and trees, looked quiet and peaceful. Checking in, I was told to be ready at 8 a.m. the next morning for a jeep ride. “No thank you,” I said. I was very sore after our bumpy ride from Kathmandu. “I’m happy to stay here tomorrow.” The young man seemed determined to give me a replacement activity.

“Do you like to walk?”

“Yes,” I said, “but not too hilly.”

“How long a walk would you like?” he asked. I suggested leaving about 10, taking a lunch and walking about four hours. He said that would work.

After a good night’s sleep and delicious breakfast, my guide appeared. I confirmed we would be doing a four hour walk. He nodded yes, but said, he had to do a pickup. I thought he meant “pick up other tourists” but no, he meant pick up another guide. The second guide didn’t speak English. I was told to walk between them. A sobering thought: two men, me, no whistle or phone. What kind of walk was this?

After a good night’s sleep and delicious breakfast, my guide appeared. I confirmed we would be doing a four hour walk. He nodded yes, but said, he had to do a pickup. I thought he meant “pick up other tourists” but no, he meant pick up another guide. The second guide didn’t speak English. I was told to walk between them. A sobering thought: two men, me, no whistle or phone. What kind of walk was this?

They both carried a large stick. When I asked where my stick was the English speaking guide said I didn’t need one: they would look after me as we stalked rhinos. Stalk rhinos? Really? He went on to say rhinos had poor eyesight but a superior sense of smell, might look slow and heavy but could charge at 30 – 40 mph. My instructions, should this happen? Climb a tree or run zig-zag. I thought he was being dramatic. He wasn’t.

It was cool in the jungle. It seemed to throb with unseen excitement. The guide was very knowledgeable, naming birds and identifying unusual bugs and interesting sounds. There were monkeys, ant eaters, ant hills, a wild boar, (thankfully uninterested in us). This was the type of walk I had expected.

It was cool in the jungle. It seemed to throb with unseen excitement. The guide was very knowledgeable, naming birds and identifying unusual bugs and interesting sounds. There were monkeys, ant eaters, ant hills, a wild boar, (thankfully uninterested in us). This was the type of walk I had expected.

After about an hour of fairly easy walking, I saw what looked like a solid brown fence about four feet high, five or six feet long. It was a giant pile of poop. As we carefully walked past it, the guide explained rhinos’ make communal latrines to mark their territory. He said, “one rhino poops about 400 pounds a day.” Rhinos? I had forgotten we were supposed to be stalking them.

Suddenly both guides put a finger to their lips and dropped onto their haunches. I hadn’t seen or heard anything but dropped down too. My heart was hammering. What on earth was I doing? One guide motioned me to creep forward. At the same time the other guide mouthed “Run!”

At the age of seventy there was no way I could climb a tree, so the second guide and I zig-zagged, between the trees, until motioned back to where the first guide still crouched. We slowly and quietly crept forward.

As I peered through trees and tall grass, I saw an open area. A one horned rhino, the size of a Volkswagen bus and dressed in heavy armour, was moving slowing, munching vegetation. We had only a couple of minutes to watch before he stopped moving and raised his head. He had caught our scent. We got out of there quickly.

As I peered through trees and tall grass, I saw an open area. A one horned rhino, the size of a Volkswagen bus and dressed in heavy armour, was moving slowing, munching vegetation. We had only a couple of minutes to watch before he stopped moving and raised his head. He had caught our scent. We got out of there quickly.

Was the day’s excitement over? No! We climbed a steep set of steps to a platform where we would be safe to eat lunch. The view was magnificent. We could hear the calls of the jungle and see the river. Far away on a high bank two men, (with an elephant), were cutting long grasses. The elephant was their transport vehicle.

The guide told me more about one-horned rhinos. In the last century poachers killed them for their horns. Only 200 remained world wild but with protection, numbers were increasing.

Finishing our late lunch, I told the guide I wanted to head back to the lodge. He nodded, “yes.”

We were walking in a sandy belt bordered by dark forest and thick undergrowth. The area was open with no protection from the burning sun. I was thinking I had very little water left when the front guide stopped. Bending down, he said, “fresh tracks, a tiger, likely male by the size of the print, was here not long ago”.

The prints were huge, as big as the width of my outstretched fingers and thumb. The guides were very excited. The English speaking one said, “There used to be many tigers in Chitwan but poachers drastically reduced their numbers. Male tigers can be up to 11 feet in length, 3 1/2-feet to their shoulder and can weigh up to 500 pounds. They prefer to stay hidden and far away from noisy jeeps so few tourists ever see them”. He added that neither he nor the other guide had seen one in the last eighteen months. “But we might be lucky today,” he said.

I didn’t want to be lucky. I wanted to get the hell out of there. I was told, “Don’t speak, walk slowly, listen carefully.” If we found where the tiger was, (or more likely, he found us), I should make eye contact and slowly back away. “You must not run!” he told me sternly.

We walked slowly and carefully for another 20 – 30 minutes. The front guide stopped suddenly, nodding his head to the left. Both guides, raising their sticks, moved in close on either side of me. Having heard and seen nothing, I followed their gaze 25 or 30 feet ahead. Standing perfectly still, almost the same height as me, I held my breath, as shining yellowish eyes locked on mine. Mostly hidden in the trees and undergrowth, I had only a few seconds to make out some white marks and black streaks around an orangey brown face and I could glimpse a little of the colour and outline of his body.

We walked slowly and carefully for another 20 – 30 minutes. The front guide stopped suddenly, nodding his head to the left. Both guides, raising their sticks, moved in close on either side of me. Having heard and seen nothing, I followed their gaze 25 or 30 feet ahead. Standing perfectly still, almost the same height as me, I held my breath, as shining yellowish eyes locked on mine. Mostly hidden in the trees and undergrowth, I had only a few seconds to make out some white marks and black streaks around an orangey brown face and I could glimpse a little of the colour and outline of his body.

“Eye contact, back away slowly,” the guide muttered. As we backed away the guides, yelling furiously, banged their sticks on the ground. The tiger kept staring. My instinct was to run. “I must not, I must not,” I said to myself.

We kept moving backward for what seemed ages but was likely only a few minutes. I saw a slight movement of the tall grass. The big cat disappeared into the thick forest. We continued walking backwards until the guide, sweat pouring down his face, said “He’s gone. What a day!”

It had been an exhilarating but scary day. The only other humans we had seen were the two men with their elephant. Very naïve and unprepared, I was happy to be safe. The four hour peaceful walk, I had expected, had turned into an eight-hour adventure. My feet were sore, I was desperate for a toilet.

If You Go:

How to get to Chitwan National Park from Kathmandu

Bus, rent a car or fly: When I went to Chitwan the road was terrible. The bus could take up to 12 hours. Today the road has been improved and you can reach Chitwan from Kathmandu in 5 – 6 hours.

thelongestwayhome.com/travel-guides/nepal/how-to-travel-to-chitwan-national-park-sauraha.html

Accommodation: Chitwan has many places to stay ranging in price from reasonable to expensive. I stayed at Green Mansions Jungle Resort which I would recommend. Steps from the Rapt River, the grounds were beautifully groomed, rooms lovely and clean, food delicious, staff friendly and helpful.

The prices to bus and stay at Green Mansions Jungle Resort have gone up considerably since I booked an all-inclusive 3- night package in 2014 for US$327.00. I booked while in Nepal so that might account for some of the price difference.

Nepal Special Tour – Kathmandu Chitwan and Pokhara

About the author:

Renee caught by the travel bug when she was twenty-one and spent four months in Europe. With little money, walking a lot, carrying her suitcase, (no wheels in 1960), her shoes were re-soled twice. Later, living in Switzerland for three years, she further explored Europe by Volkswagen bus. An RN / Lactation Consultant, she has worked in Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines and the Emirates. In 2014 she volunteered at a school for Himalayan Nepali children. Weekends were spent exploring Nepal. She continues to travel for pleasure; her camera always near-by.

3-Day Chitwan Wildlife Safari Tour from Kathmandu

First photo by John Nabelek licensed by Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Photos 2 – 5 by Renee Hefti-Graham

Tiger photo by AceVisionNepal77 / CC BY-SA

As I walked through the streets of the ancient city a resting group of riot policemen posed for a candid picture. This was a time when civil war was on the mountain kingdom’s doorstep. Every day rioting took place in the capital of Kathmandu. It looked as though the country was about to self-destruct.

As I walked through the streets of the ancient city a resting group of riot policemen posed for a candid picture. This was a time when civil war was on the mountain kingdom’s doorstep. Every day rioting took place in the capital of Kathmandu. It looked as though the country was about to self-destruct. I think a lot about those sites now. My hotel was close to Durbar Square in Katmandu – being only a brisk 10 minute walk in the cold December morning air. The first morning I arrived just as the hawkers were setting out their antiques and replicas for sale on large tarps in the outskirts of the square. Many invited me to bring them good luck by being their first sale of the day. As I walked around the square it was like stepping back hundreds of years. Beautiful temples washed in a deep red pigment paint and tile roofs in deep burnt umbra color above gave it a true organic feel. The early morning air was impregnated with the rich smells of temple incense and fresh cut flowers as the first orange colored beams of sunlight took the chill away. Ladies, dressed in traditional colorful mountain village clothes, sat on large plastic mats selling strings of brightly colored marigolds formed into necklaces and headbands.

I think a lot about those sites now. My hotel was close to Durbar Square in Katmandu – being only a brisk 10 minute walk in the cold December morning air. The first morning I arrived just as the hawkers were setting out their antiques and replicas for sale on large tarps in the outskirts of the square. Many invited me to bring them good luck by being their first sale of the day. As I walked around the square it was like stepping back hundreds of years. Beautiful temples washed in a deep red pigment paint and tile roofs in deep burnt umbra color above gave it a true organic feel. The early morning air was impregnated with the rich smells of temple incense and fresh cut flowers as the first orange colored beams of sunlight took the chill away. Ladies, dressed in traditional colorful mountain village clothes, sat on large plastic mats selling strings of brightly colored marigolds formed into necklaces and headbands. In the afternoon we traveled to the Hindu temple of Pashupatinath. As we came around a corner onto a stone carved staircase and ashram there he sat. I can never forget that moment – the thousand mile stare of the Sadu as he looked through me as if I wasn’t there. With his legs crossed in a yoga pose, he was looking over the ceremonies on the other side of the river. Here the recently departed were being bathed in the holy water from the Bagmati River, dressed in colorful silk and placed on carefully stacked wood funeral pyres for their cremation. The holy man did not blink, move, or change any expression. It all seemed surreal me – like I was in a dream. Here I was in the holiest of Hindu temples in Kathmandu, Nepal. A week earlier on my flight to India I had not even planned to visit Nepal as part of my tour. It was close enough to my destination of Varanasi, in eastern India, that the tour company had recommended it as a side excursion during my month long road trip.

In the afternoon we traveled to the Hindu temple of Pashupatinath. As we came around a corner onto a stone carved staircase and ashram there he sat. I can never forget that moment – the thousand mile stare of the Sadu as he looked through me as if I wasn’t there. With his legs crossed in a yoga pose, he was looking over the ceremonies on the other side of the river. Here the recently departed were being bathed in the holy water from the Bagmati River, dressed in colorful silk and placed on carefully stacked wood funeral pyres for their cremation. The holy man did not blink, move, or change any expression. It all seemed surreal me – like I was in a dream. Here I was in the holiest of Hindu temples in Kathmandu, Nepal. A week earlier on my flight to India I had not even planned to visit Nepal as part of my tour. It was close enough to my destination of Varanasi, in eastern India, that the tour company had recommended it as a side excursion during my month long road trip. Along the streets of the old city, mixed with temples, were the fruit and vegetable sellers. Everything looked freshly picked even though the temperatures dipped below freezing at night time. Spices were overflowing out of huge containers – cumin, turmeric, and curries. The air had the smell of fragrant local food from the small portable stalls that sold all kinds of savory items. It was a feeling of being alive in those streets – excitement, anticipation, exotic smells and tastes.

Along the streets of the old city, mixed with temples, were the fruit and vegetable sellers. Everything looked freshly picked even though the temperatures dipped below freezing at night time. Spices were overflowing out of huge containers – cumin, turmeric, and curries. The air had the smell of fragrant local food from the small portable stalls that sold all kinds of savory items. It was a feeling of being alive in those streets – excitement, anticipation, exotic smells and tastes.

The next morning we decided to take a walk in Kathmandu. Durbar Square was our first and natural destination. The word Durbar Square may be equivalent to German Marktplatz. Several Nepalese cities have Durbar Squares, which are usually made up of royal and religious buildings. The Kathmandu Durbar Square, which is not free of charge for foreigners to enter, can present a variety of royal courts, temples and monuments (most of them belong to different historical periods), as well as numerous guides and street sellers, who would stalk you all the time and offer their goods and services. Tourists who have some understanding in history and religion, especially that of Indian subcontinent, can be very happy to explore every corner of the square. But even if you do not posses this kind of information, no worries at all. Dozens of guides are always ready to lead you by explaining the history and meaning of each edifice.

The next morning we decided to take a walk in Kathmandu. Durbar Square was our first and natural destination. The word Durbar Square may be equivalent to German Marktplatz. Several Nepalese cities have Durbar Squares, which are usually made up of royal and religious buildings. The Kathmandu Durbar Square, which is not free of charge for foreigners to enter, can present a variety of royal courts, temples and monuments (most of them belong to different historical periods), as well as numerous guides and street sellers, who would stalk you all the time and offer their goods and services. Tourists who have some understanding in history and religion, especially that of Indian subcontinent, can be very happy to explore every corner of the square. But even if you do not posses this kind of information, no worries at all. Dozens of guides are always ready to lead you by explaining the history and meaning of each edifice. Although the Durbar Square contains a lot of historical buildings, it would take too long to explain each of them. But one should certainly visit the Kumari residence. Kumari is a living goddess mainly worshipped by Hindus. In Nepal Kumari is a pre-pubescent girl regularly determined as a result of interesting and complex selection process.

Although the Durbar Square contains a lot of historical buildings, it would take too long to explain each of them. But one should certainly visit the Kumari residence. Kumari is a living goddess mainly worshipped by Hindus. In Nepal Kumari is a pre-pubescent girl regularly determined as a result of interesting and complex selection process. For people, who are eager to see Mt. Everest and some other peaks, I would highly recommend you to take a mountain flight operated by a bunch of domestic airlines in Nepal. As I mentioned above, even small hotels can arrange mountain flights, which can make your job more convenient. You will be taken very high, above the clouds, to the Roof of the World. Kind stewards will show and explain you every of a dozen Himalayan peaks. You can even get a chance to enter to the pilot`s cabin, where an indescribably wonderful and magnificent view will open in front of you. I am sure this mountain flight will be one of the most memorable moments you will recall with a pleasure the rest of your life. But Nepal is not only the Everest. Proud of their history, every Nepalese may tell you their country is the birthplace of Gautama Buddha. The founder of Buddhism was born in 6th century BC in Lumbini, a small town in the southern part of the country. Today Lumbini is a worshipping place, where many Buddhists from all over the world, not only from Nepal come to pay their tribute.

For people, who are eager to see Mt. Everest and some other peaks, I would highly recommend you to take a mountain flight operated by a bunch of domestic airlines in Nepal. As I mentioned above, even small hotels can arrange mountain flights, which can make your job more convenient. You will be taken very high, above the clouds, to the Roof of the World. Kind stewards will show and explain you every of a dozen Himalayan peaks. You can even get a chance to enter to the pilot`s cabin, where an indescribably wonderful and magnificent view will open in front of you. I am sure this mountain flight will be one of the most memorable moments you will recall with a pleasure the rest of your life. But Nepal is not only the Everest. Proud of their history, every Nepalese may tell you their country is the birthplace of Gautama Buddha. The founder of Buddhism was born in 6th century BC in Lumbini, a small town in the southern part of the country. Today Lumbini is a worshipping place, where many Buddhists from all over the world, not only from Nepal come to pay their tribute.

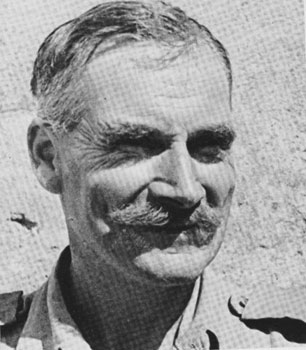

Well over a half century ago the inveterate British mountaineer and travel writer, H.W. ‘Bill’ Tilman (b.1898), was the first European to trek across some of the highest parts of Nepal. It was 1949, and one of his stops was the sacred Hindu/Buddhist pilgrimage shrine of Muktinath, near the Tibet border on the north side of the Annapurna massif.

Well over a half century ago the inveterate British mountaineer and travel writer, H.W. ‘Bill’ Tilman (b.1898), was the first European to trek across some of the highest parts of Nepal. It was 1949, and one of his stops was the sacred Hindu/Buddhist pilgrimage shrine of Muktinath, near the Tibet border on the north side of the Annapurna massif.

Tilman’s Nepal Himalaya was our guide. It’s a classic of the Himalayan literature, one that belongs in the personal library of every ardent or aspiring mountaineer and trekker. It is notable not only for its descriptions of the medieval-like conditions of rural Nepal over half a century ago, but for the author’s unique candor and style.

Tilman’s Nepal Himalaya was our guide. It’s a classic of the Himalayan literature, one that belongs in the personal library of every ardent or aspiring mountaineer and trekker. It is notable not only for its descriptions of the medieval-like conditions of rural Nepal over half a century ago, but for the author’s unique candor and style. Tilman’s prose was more serious, informative and insightful, but no less entertaining. For example, in one chapter of his book he wrote, tongue-in-cheek, that he and his companions failed to summit Annapurna-IV (24,688 ft) simply because of an “inability to reach the top.”

Tilman’s prose was more serious, informative and insightful, but no less entertaining. For example, in one chapter of his book he wrote, tongue-in-cheek, that he and his companions failed to summit Annapurna-IV (24,688 ft) simply because of an “inability to reach the top.” His party “camped near the topmost house of the straggling village where our arrival created no stir. A place to which several thousand pilgrims come every year must be accustomed to strange sights.”

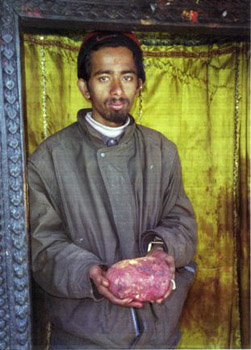

His party “camped near the topmost house of the straggling village where our arrival created no stir. A place to which several thousand pilgrims come every year must be accustomed to strange sights.” Tilman noted that Muktinath “owes its sanctity to the presence of the thrice-sacred ‘shaligram’,” the local name for black ammonite fossils found in abundance in this locale. Hindus worship the coiled shaligrams as representations of Lord Vishnu. Buddhists consider them to represent Gawo Jogpa, a serpent deity. Geologically they date back 165 million years to a time when this high-rise landscape lay covered by mud at the bottom of the Tethys Sea. Back then, long before the Himalayas were formed, the shallow Tethys separated Gondwanaland (today’s Indian subcontinent) from Laurasia (the Tibetan plateau). You can well imagine the looks of wonder in the eyes of today’s pilgrims from the plains upon finding the encrustations of ancient sea creatures so high in the mountains.

Tilman noted that Muktinath “owes its sanctity to the presence of the thrice-sacred ‘shaligram’,” the local name for black ammonite fossils found in abundance in this locale. Hindus worship the coiled shaligrams as representations of Lord Vishnu. Buddhists consider them to represent Gawo Jogpa, a serpent deity. Geologically they date back 165 million years to a time when this high-rise landscape lay covered by mud at the bottom of the Tethys Sea. Back then, long before the Himalayas were formed, the shallow Tethys separated Gondwanaland (today’s Indian subcontinent) from Laurasia (the Tibetan plateau). You can well imagine the looks of wonder in the eyes of today’s pilgrims from the plains upon finding the encrustations of ancient sea creatures so high in the mountains. The fires of Jwala Mai were first described in English by David Snellgrove, a British Tibetologist who visited Muktinath in 1956. In his book, Himalayan Pilgrimage (1961), Snellgrove wrote that “The flames of natural gas burn in little caves at floor level in the far right-hand corner. One does indeed burn from earth; one burns just beside a little spring (‘from water’); and one ‘from stone’ exhausted itself two years ago [1954] and so burns no longer, at which local people express concern.”

The fires of Jwala Mai were first described in English by David Snellgrove, a British Tibetologist who visited Muktinath in 1956. In his book, Himalayan Pilgrimage (1961), Snellgrove wrote that “The flames of natural gas burn in little caves at floor level in the far right-hand corner. One does indeed burn from earth; one burns just beside a little spring (‘from water’); and one ‘from stone’ exhausted itself two years ago [1954] and so burns no longer, at which local people express concern.” On the secular side of Muktinath, the physical facilities available to pilgrims consist primarily of uncomfortable cold stone shelters wide open to the elements. In recent years, several tourist hotels and trekkers’ guesthouses have been built at Rani Pauwa (‘Queen’s Resthouse’), a small settlement below the shrine. They bear such names as Shri Muktinath Hotel and Royal Mustang Hotel, and one that is inexplicably named after Bob Marley, the renowned Rastafarian musician.

On the secular side of Muktinath, the physical facilities available to pilgrims consist primarily of uncomfortable cold stone shelters wide open to the elements. In recent years, several tourist hotels and trekkers’ guesthouses have been built at Rani Pauwa (‘Queen’s Resthouse’), a small settlement below the shrine. They bear such names as Shri Muktinath Hotel and Royal Mustang Hotel, and one that is inexplicably named after Bob Marley, the renowned Rastafarian musician. I set out to trace the etymological roots of “resort,” the noun. In Roget’s Thesaurus I found a long list of synonyms: haunt, hangout, playground, vacation spot, gathering place, club, and casino. A place for recreation, like a ski lodge. A health spa, baths or springs. All the things we expect a “resort” to be. The only association between these contemporary descriptors and Muktinath’s ascetic reality are those “hundred-odd” cold mountain springs. But I can’t imagine Tilman cavorting playfully in the frigid waters then calling it a “resort.”

I set out to trace the etymological roots of “resort,” the noun. In Roget’s Thesaurus I found a long list of synonyms: haunt, hangout, playground, vacation spot, gathering place, club, and casino. A place for recreation, like a ski lodge. A health spa, baths or springs. All the things we expect a “resort” to be. The only association between these contemporary descriptors and Muktinath’s ascetic reality are those “hundred-odd” cold mountain springs. But I can’t imagine Tilman cavorting playfully in the frigid waters then calling it a “resort.”

There are three Durbar Squares in Kathmandu valley named Hanumandhoka, Patan & Bhaktapur. A Durbar Square is a settlement with the King’s palace at its centre, surrounded by the temples dedicated to deities of the clan. This used to be the centre of the town and around this everyone else would live. As you see the squares today, you would see how these squares had the beautiful buildings with spaces for people to sit around and how these squares more or less merged with the rest of the town. Even today these squares are very much living spaces and you would see local people sitting on the steps of the temples and on the corridors outside the buildings. There is no formal boundary between the durbar squares and the residential areas. In fact there are no tickets for the locals to visit these places only the foreigners have to pay an entrance fees for all the three durbar squares. Some parts have now been converted into commercial establishments like shops and restaurants. Some of the palaces or their parts have been converted into museums. With Pagoda style architecture all of them are beautiful in their own way, while being very similar to each other. Most of the buildings are in red brick with intricately carved wooden windows, which are the trademark of Nepal.

There are three Durbar Squares in Kathmandu valley named Hanumandhoka, Patan & Bhaktapur. A Durbar Square is a settlement with the King’s palace at its centre, surrounded by the temples dedicated to deities of the clan. This used to be the centre of the town and around this everyone else would live. As you see the squares today, you would see how these squares had the beautiful buildings with spaces for people to sit around and how these squares more or less merged with the rest of the town. Even today these squares are very much living spaces and you would see local people sitting on the steps of the temples and on the corridors outside the buildings. There is no formal boundary between the durbar squares and the residential areas. In fact there are no tickets for the locals to visit these places only the foreigners have to pay an entrance fees for all the three durbar squares. Some parts have now been converted into commercial establishments like shops and restaurants. Some of the palaces or their parts have been converted into museums. With Pagoda style architecture all of them are beautiful in their own way, while being very similar to each other. Most of the buildings are in red brick with intricately carved wooden windows, which are the trademark of Nepal.

Bhaktapur is an old town and is considered the cultural capital of the region. This square actually has three squares. You see the first one as you enter from the main gate called the Durbar Square. Past this is Taumadhi Square, which has the magnificent five-storied Nyatapola temple dedicated to Siddhi Laxmi along with a three-storey Bhairav temple. The steps leading to the temple have huge figurines of animals on both sides. From the top story of the temple you can get a bird’s eye view of the town. Behind this square is a potter’s square where you will see rows of pottery lying in a square and potter’s wheels around it.

Bhaktapur is an old town and is considered the cultural capital of the region. This square actually has three squares. You see the first one as you enter from the main gate called the Durbar Square. Past this is Taumadhi Square, which has the magnificent five-storied Nyatapola temple dedicated to Siddhi Laxmi along with a three-storey Bhairav temple. The steps leading to the temple have huge figurines of animals on both sides. From the top story of the temple you can get a bird’s eye view of the town. Behind this square is a potter’s square where you will see rows of pottery lying in a square and potter’s wheels around it. Swayambhunath is located on a small hilltop inside the city. There is a large stupa surrounded by many temples and lots of Mandalas spread all over the complex. The stupa dates back to 5th century with an interesting story of a lotus being converted into this hill. Apart from the magnificent stupa with intriguing eyes painted on it, you can get an excellent view of the Kathmandu city from this high vantage point.

Swayambhunath is located on a small hilltop inside the city. There is a large stupa surrounded by many temples and lots of Mandalas spread all over the complex. The stupa dates back to 5th century with an interesting story of a lotus being converted into this hill. Apart from the magnificent stupa with intriguing eyes painted on it, you can get an excellent view of the Kathmandu city from this high vantage point.