by Chris Brauer

Down the beach, the sky was full of circling birds. They squawked and shrieked to show their disapproval at being denied free food while they took turns swooping towards a crowd of young Omani men pulling enormous nets out of the water with the help of small Toyota trucks that sunk into the sand. The men, dressed in mundus and various shirts, jerseys and dishdashas, yelled out encouragement.

Some of the men had bunched up the fabric around their waists to prevent from getting wet, but most seemed too involved in hauling in their catch of sardines to worry about wet clothes. Older Omani men with white wizened beards leaned on their thin walking sticks or circled around the fishermen. Occasionally they whacked the side of the truck to let the driver know he was sinking instead of finding traction. A few more sat on the sand, closer to the corniche, with old nets spread out in front of them, sewing up any holes from overuse. We walked close enough to see what was going on but kept our distance so as not to get in the way.

Some of the men had bunched up the fabric around their waists to prevent from getting wet, but most seemed too involved in hauling in their catch of sardines to worry about wet clothes. Older Omani men with white wizened beards leaned on their thin walking sticks or circled around the fishermen. Occasionally they whacked the side of the truck to let the driver know he was sinking instead of finding traction. A few more sat on the sand, closer to the corniche, with old nets spread out in front of them, sewing up any holes from overuse. We walked close enough to see what was going on but kept our distance so as not to get in the way.

“Where can we walk to from here and explore?” asked Paula.

“The frankincense souk is about a half-hour’s walk down the road — maybe forty minutes. It’s at the far end of Al Haffa.”

“Let’s go there, then. That’s sounds interesting.”

“It is, yes. But I was thinking about Nicholas and his aversion to sitting in his stroller for any length of time. A half-hour walk may be considerably longer at Nicholas’ speed.”

“It’ll be fine. He’ll tire out and want to nap.”

I wasn’t so sure. I anticipated having to spend the entire walk leaning over, arms outstretched at a frantic run, as Nicholas at the age of two zigzagged up and down the street.

After twenty minutes, Nicholas was visibly tired and I convinced him to sit in his stroller where he soon fell asleep. I encouraged the rest of the family to walk a little faster, making the most of the time, but Paula wasn’t interested in doing that. “He’ll be fine,” she said.

We walked into the first wide alleyway of the souk. I showed Paula and her mom the two side-by-side shops that sold pashmina shawls and various patterned thuds.

We walked into the first wide alleyway of the souk. I showed Paula and her mom the two side-by-side shops that sold pashmina shawls and various patterned thuds.

“Thuds only consist of a tent of fabric with two armholes,” I said. “And they are so gaudy, with the worst possible colours and patterns imaginable.”

“That sounds perfect. They’ll be light and airy,” said Paula.

“Yeah, maybe. But they are really gaudy.”

“Uh-huh. Can you watch Nicholas for a bit while Mom and I look inside?”

“I’ll just wait outside, then, shall I?”

“Yes, please.”

Nicholas woke up from his short nap and wasn’t interested in being strapped into his stroller anymore, so I heaved him up onto my shoulders. As we walked around, a woman behind one of the frankincense stalls smiled at me. I thought she recognized me from school, so I went over but she was more interested in Nicholas than me. She giggled when Nicholas started bouncing on my shoulders, burning my neck, and she shook with laughter as Nicholas covered my eyes, getting his greasy fingers all over my glasses while he searched for finger holds in my nostrils and the roof of my mouth.

She composed herself and held up her index finger. A bag of frankincense was one rial. I paid and, with frankincense in hand, we checked in on the rest of the family. They were still going through multiple stacks. A pile of two or three pashimas and a-half dozen thuds were already on the counter. With Nicholas now off my shoulders, we continued our walk through the souk.

She composed herself and held up her index finger. A bag of frankincense was one rial. I paid and, with frankincense in hand, we checked in on the rest of the family. They were still going through multiple stacks. A pile of two or three pashimas and a-half dozen thuds were already on the counter. With Nicholas now off my shoulders, we continued our walk through the souk.

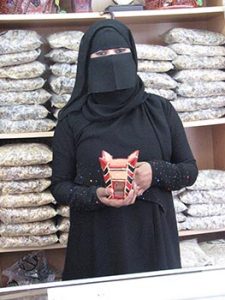

We made our way along a couple of narrower alleyways where older Omani women cloaked in black were selling bags of frankincense and traditional clay burners from Mirbat (a fishing village an hour up the eastern coast). The women made clicking noises with their tongues to get Nicholas’ attention but he ignored them. We peered into a few shops, some lined with little jars of saffron from Iran and some full of little bottles of amber-coloured perfume. We passed a group of older men in the open square, all drinking sweet tea and dressed in white dishdashas.

“‘As-salaam ‘alaykum,” I said.

“‘Alaykum salaam”, they mumbled back, uninterested.

We followed the smells emanating from a little restaurant where the cooks were serving up chicken masala and mutton tikka to the young men who were hunkered over their food like vultures. Then we heard the call to prayer. It startled Nicholas, but he accepted it as part of his day. Nicholas, a week before his second birthday, had no concept that this Arabian world was different in any way. While adults see the differences between groups of people, children see the similarities.

We followed the smells emanating from a little restaurant where the cooks were serving up chicken masala and mutton tikka to the young men who were hunkered over their food like vultures. Then we heard the call to prayer. It startled Nicholas, but he accepted it as part of his day. Nicholas, a week before his second birthday, had no concept that this Arabian world was different in any way. While adults see the differences between groups of people, children see the similarities.

Looking at breakable clay incense burners with a toddler sounds like a bad idea, but that’s what I did. The first time I saw the gaudy clay burners, complete with gold hearts and rainbow sparkles, I assumed that they were made for tourists but locals loved their rainbow sparkles. This time, with Nicholas, I wasn’t in a position to worry about hearts and sparkles; I was too busy making sure his curious fingers didn’t knock anything over.

As Nicholas ran from place to place, never in a straight line, I watched as shopkeepers smiled and waved at him, sometimes offering him little Kit-Kat bars or mango juice. For ten weeks I had tried to understand why there was such a dramatic difference between the reality of day-to-day life in Salalah and the blanket statements made by the American media regarding the entire Middle East. I understood now that Oman was a friendly and welcoming country, but there were a couple times when I experienced doubt as to whether moving my family to southern Arabia was the best decision. While I wanted my children to grow up with confidence, independence, and a sense of the world, I wondered if this was too extreme. As a father I wondered if a Western toddler was a target for kidnappers and smugglers. As we walked around the souk, still waiting for Paula, Adam and Grandma to finish, I realized I had faith. I knew that humanity was inherently good and not evil. I felt safe and I felt Nicholas was safe, which was good because I soon lost him. As I looked around frantically, the shopkeepers laughed as they pointed me down a narrow alleyway. When I found him, he was holding hands with an Omani woman, her kind eyes hinting at a smile behind the veil.

As Nicholas ran from place to place, never in a straight line, I watched as shopkeepers smiled and waved at him, sometimes offering him little Kit-Kat bars or mango juice. For ten weeks I had tried to understand why there was such a dramatic difference between the reality of day-to-day life in Salalah and the blanket statements made by the American media regarding the entire Middle East. I understood now that Oman was a friendly and welcoming country, but there were a couple times when I experienced doubt as to whether moving my family to southern Arabia was the best decision. While I wanted my children to grow up with confidence, independence, and a sense of the world, I wondered if this was too extreme. As a father I wondered if a Western toddler was a target for kidnappers and smugglers. As we walked around the souk, still waiting for Paula, Adam and Grandma to finish, I realized I had faith. I knew that humanity was inherently good and not evil. I felt safe and I felt Nicholas was safe, which was good because I soon lost him. As I looked around frantically, the shopkeepers laughed as they pointed me down a narrow alleyway. When I found him, he was holding hands with an Omani woman, her kind eyes hinting at a smile behind the veil.

Half day tour Splendours of the East :Salalah Tours :Oman Shore excursions

If You Go:

Where to stay:

Crowne Plaza Salalah

About the author:

Chris Brauer lives in Creston, British Columbia, where he splits his time between writing and teaching. He has recently completed a travel memoir about living in the Sultanate of Oman, and is currently working on a book about his travels in Ireland. He is also working on his first collection of poetry.

Photo Credits:

The view from our villa in the neighbourhood of Al Haffa in Salalah, Oman — Chris Brauer

An older Omani man hauling in nets of sardines along the beach — Anne Bowen

Three men having a smoke break at the frankincense souk in Salalah — Anne Bowen

Basket of frankincense, the resin from the Boswellia tree — Paula Ebelher

An Omani woman selling frankincense and burners at the souk — Paula Ebelher

Gun traders at the frankincense souk in Salalah — Anne Bowen

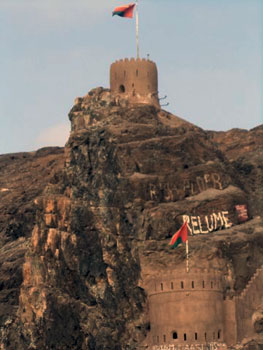

The discovery of oil however has given the country an unprecedented economical boost and it is my very personal opinion that the wealthy past has determined that the billions of petro dollars have been put to brilliant use. There is absolutely nothing ‘nouveau riche’ about modern Muscat. The difference to nearby Dubai is striking. Muscat has only one high rise, the Hilton Hotel and that has only 14 stories. Otherwise the buildings have all been designed in traditional Omani style with round towers, huge walls, carved wooden doors and small windows to keep out the heat. The only colors in evidence are white and sand, no garish paint, no gold, no colorful tiles, no adornment other than stone arabesques carved into the mantels. The overall impression is of cool elegance and understated wealth. Very, very soothing on the eye and beautifully in harmony with the country.

The discovery of oil however has given the country an unprecedented economical boost and it is my very personal opinion that the wealthy past has determined that the billions of petro dollars have been put to brilliant use. There is absolutely nothing ‘nouveau riche’ about modern Muscat. The difference to nearby Dubai is striking. Muscat has only one high rise, the Hilton Hotel and that has only 14 stories. Otherwise the buildings have all been designed in traditional Omani style with round towers, huge walls, carved wooden doors and small windows to keep out the heat. The only colors in evidence are white and sand, no garish paint, no gold, no colorful tiles, no adornment other than stone arabesques carved into the mantels. The overall impression is of cool elegance and understated wealth. Very, very soothing on the eye and beautifully in harmony with the country. Already in love with the serene beauty of modern Muscat, my friend and I decided to visit the Muttrah souk, one of the oldest souks in all of the Middle East. During Ramadan, the souk is only open at night and, as Eid was approaching, people were out in doves to shop for clothes, jewelry and gifts in preparation for the festivities marking the end of the holy month. Two things held our attention: the ever present scent of frankincense which burns in every doorway and is one of the most important items on offer and the beautifully carved roof, reflecting the age old art of Omani wood carvings. In fact, so important is frankincense to Oman that a huge burner, high up on a hill is one of the most famous landmarks of Muscat.

Already in love with the serene beauty of modern Muscat, my friend and I decided to visit the Muttrah souk, one of the oldest souks in all of the Middle East. During Ramadan, the souk is only open at night and, as Eid was approaching, people were out in doves to shop for clothes, jewelry and gifts in preparation for the festivities marking the end of the holy month. Two things held our attention: the ever present scent of frankincense which burns in every doorway and is one of the most important items on offer and the beautifully carved roof, reflecting the age old art of Omani wood carvings. In fact, so important is frankincense to Oman that a huge burner, high up on a hill is one of the most famous landmarks of Muscat. The next day we wanted to explore Muscat some more and also visit the part known as Old Muscat. To our disappointment, there is next to no public transport. We love to travel on local buses. But, at a price of 50cents for a liter of gas it doesn’t come as a surprise that everybody has at least one car. So, we took a taxi, passing by the modern, exquisite shopping complex in Ruwi on our way to the Sultan’s palace. It’s the only colorful building in blue and gold with nearly identical front and back which can be seen from the landside as well as from the water.

The next day we wanted to explore Muscat some more and also visit the part known as Old Muscat. To our disappointment, there is next to no public transport. We love to travel on local buses. But, at a price of 50cents for a liter of gas it doesn’t come as a surprise that everybody has at least one car. So, we took a taxi, passing by the modern, exquisite shopping complex in Ruwi on our way to the Sultan’s palace. It’s the only colorful building in blue and gold with nearly identical front and back which can be seen from the landside as well as from the water. The first took us out to sea to watch dolphins at play, the second along the breath taking coastline with alternating rock formations in white marble and black granite with tiny sand beaches in between. Boat trip #3 was dedicated to experiencing the coastline bathed in the rays of the sinking sun on board a traditional Oman dhow.

The first took us out to sea to watch dolphins at play, the second along the breath taking coastline with alternating rock formations in white marble and black granite with tiny sand beaches in between. Boat trip #3 was dedicated to experiencing the coastline bathed in the rays of the sinking sun on board a traditional Oman dhow.