Santa Ana, California

by Debra Young

Sometimes you don’t have to go far to find yourself in another time, almost in another world. Last July, I viewed the Secrets of the Silk Road Exhibition at the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana, California and stepped 3800 years into the past to the days of life along the Silk Road. Yak, horse and camel caravans carried silk, salt, silver, gold, jade, lapis lazuli, brass, copper, medicines, wool, and more to the caravanserai, the market towns and trade cities with fabulously exotic names — Lanzhou, Koko-Nor, Charklick, Khotan, Yarkana, Yangi-hissar, Kashgar, Aksu, Kucha, Lop Nor. I was reminded that our world exists through many incarnations, the rise and fall of cultures and civilizations and people.

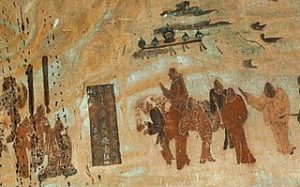

The Silk Road was not a single route, but many, a web of roads running from the Caspian Sea in the west to Chang’an, the Tang capital of eighth-century China, in the east, traversing the vast regions of Central Asia, looping over mountains and skirting deserts. On these routes journeyed merchants, monks, mercenaries, armies, and later, when the Silk Road had become an historical legend, explorers and archaeologists, drawn by stories of ruins and lost kingdoms buried in the sands. Among those lost places along the Silk Road are the cities and towns of the Tarim Basin, a region of the arid and inhospitable Taklamakan Desert in northwestern China, where once abided a Bronze Age people of European origin whose mummified bodies and the beautifully crafted objects of their daily lives have been nearly perfectly preserved by the arid conditions of the desert environment.

The Silk Road was not a single route, but many, a web of roads running from the Caspian Sea in the west to Chang’an, the Tang capital of eighth-century China, in the east, traversing the vast regions of Central Asia, looping over mountains and skirting deserts. On these routes journeyed merchants, monks, mercenaries, armies, and later, when the Silk Road had become an historical legend, explorers and archaeologists, drawn by stories of ruins and lost kingdoms buried in the sands. Among those lost places along the Silk Road are the cities and towns of the Tarim Basin, a region of the arid and inhospitable Taklamakan Desert in northwestern China, where once abided a Bronze Age people of European origin whose mummified bodies and the beautifully crafted objects of their daily lives have been nearly perfectly preserved by the arid conditions of the desert environment.

The Secrets of the Silk Road exhibit presented a hundred and fifty objects excavated from tombs of the Tarim Basin mummies along with two remarkable mummies–“The Beauty of Xiaohe” and that of a baby. A third mummy, too fragile for the rigors of travel, known as Yingpan Man, believed to be a rich Sogdian trader, was represented by a layout of his funeral mask, white with a golden diadem, and his sumptuous clothing, an elaborately patterned red and gold wool caftan, dark brown pants in an ornately embroidered diamond pattern, and gold-ornamented boots. Considering his sumptuous burial clothing, Yingpan Man was held in high regard and was no doubt a man who loved and could well afford the finest things in life.

The gem of the exhibit was “The Beauty of Xiaohe,” a well-preserved mummy of a Caucasian woman, serenely at rest through the centuries in her boat-shaped coffin, wrapped in a wool coat, fur boots on her feet, her brown hair showing from beneath the rounded brim of her fur hat, lashes fringing her sunken eyes, every inch of her a marvel preserved by the desert sands.

As I contemplated each artifact of the ancient past, those colorful silk brocades and damasks imprinted with elegant floral designs, a pair of shoes made for a girl, cream yellow with tiny writing woven in a delicate arabesque bestowing blessings on the wearer, horse blankets of ornately worked wool, meticulously decorated game boxes, gold jewelry embedded with rubies, agates, and lapis lazuli, I imagined the hands that might have held these things at one time, the voices that might have spoken of them in the extinct Tocharian language of the Tarim Basin people, and I considered the importance we now give to these artifacts, the ordinary objects of daily life long ago because they connect us in an unbroken thread of lives lived through time.

As I contemplated each artifact of the ancient past, those colorful silk brocades and damasks imprinted with elegant floral designs, a pair of shoes made for a girl, cream yellow with tiny writing woven in a delicate arabesque bestowing blessings on the wearer, horse blankets of ornately worked wool, meticulously decorated game boxes, gold jewelry embedded with rubies, agates, and lapis lazuli, I imagined the hands that might have held these things at one time, the voices that might have spoken of them in the extinct Tocharian language of the Tarim Basin people, and I considered the importance we now give to these artifacts, the ordinary objects of daily life long ago because they connect us in an unbroken thread of lives lived through time.

Among the treasures on display was a suit made as a gift for a Sogdian merchant’s young grandson, described by Susan Whitfield in “Life Along the Silk Road,” as being “a traditional Sogdian suit…a short jacket with narrow sleeves, a mandarin collar and front, central fastenings, flared slightly from the waist. The outer silk woven in blue, yellow, green, red and white with a pattern of paired facing ducks inside roundels, a typical Sogdian pattern, and a brown Chinese damask with a large-scale floral pattern for the jacket lining and trousers.” The merchant also ordered a pair of matching boots. Imagine his grandson’s delight when Grandfather returned home from his long journey bearing such finery.

I was touched by the mummy of the baby, gauged to be less than ten months old, swaddled in wool tied with red and blue cords, small flat blue stones over his eyes, and buried with a baby bottle made of a goat’s bladder. There was a fabulous gold mask of a man’s face rimmed with rubies, and excavated from the tomb of a noble couple was a figurine of a lovely dancer made of wood, silk, and clay. Her arms were made from cancelled pawn tickets. Old papers were often recycled as material for burial objects. One item that I found quite intriguing was a pair of delicately pierced eye covers, similar to sunglasses, used to shield the eyes of the dead.

There was food. Yes there was, preserved as if freeze-dried. The harsh cold of the Taklamakan Desert in winter and the heat and aridity of its summers had perfectly dehydrated pale pastries, tiny purse-sized dumplings and braided fried dough twists.

The Bowers Museum organized and debuted the Secrets of the Silk Road Exhibition, the historic, landmark tour of the artifacts from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region encompassing the Tarim Basin in the vast northwestern reaches of China. From the Bowers Museum the exhibition traveled to the Houston Museum of Natural History and then to Philadelphia’s Penn Museum where the tour ended, and the exhibition’s artifacts returned home to China.

Some people see museums as boring places, warehouses for the collection of things from the past, things that might’ve been junk in its own time, dead things, dust catchers, mildly interesting perhaps but having no relevancy to our times. Museums preserve the living past, exhibits like the Secrets of the Silk Road Exhibition show us that life is eternal in its way, the artifacts of the past resonate with life and symbolize that old saying “Life goes on.” Indeed it does. Past and future meld in the present. Museums are not simply warehouses of things from the past, preserving the dead and what used to be, they are gateways through time, bringing the past to the present. To visit the Secrets of the Silk Road Exhibition was a spiritual journey into the vast country of past lives.

If You Go:

Bowers Museum, 2002 North Main Street

Santa Ana, CA 92706

Tel: (714) 567-3600

About the author:

Debra Young lives and writes in Long Beach, California, grew up traveling in Europe and the US, and has obsessive interests in ancient history, art, and literature. She’s published fiction and non-fiction, and invites you to visit her at her blog Pendrifter at dayya.wordpress.com.

Image credits:

Desert camel caravan: by pixelRaw from Pixabay

Zhang Qian: Unknown author / Public domain

Tang dynasty city film and television base: Sherbet / CC BY