Abdurafi, Ethiopia

by Richard Currie

It’s wedding season in Abdurafi, Ethiopia. Wedding season comes but once a year, and lasts for two months only. Raise a flag, kill a goat, beat a drum, invite the neighbours and get yourself a wife! Tastefully photocopied scrap-paper wedding invitations pile up on tukul doorsteps, well fattened goats become harder to find, and the nights are filled with the throbbing of drums as wedding processions parade through the village.

Abdurafi is a small, rural farming community in northwestern Ethiopia. I work here for Medicines Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders) at a hospital run by six expatriate medical aid workers, 40 Ethiopian health care professionals, and a large support staff from the local community

The town is positively rabid with wedding fever. So it came as no surprise when Yohannes, one of our community health educators , came to the office late last week and invited everyone to his wedding. “I’m getting married on Saturday,” he announced. Saturdays are regular work days in Ethiopia, at least until noon. Yohannes was quick to reassure us that the wedding wouldn’t start until four o’clock ferenje (foreigner’s) time. And no, he didn’t wish to take the morning off. Perhaps he could have Monday off for a honeymoon instead?

We were delighted to be invited. How often does one get the chance to attend an authentic Amharic wedding ceremony in rural Ethiopia?

Having happily accepted the invitation my colleagues and I set about trying to find the perfect wedding gift. In a small place like Abdurafi, this was no easy task. There are about a hundred grass-roofed tin-walled shops and stalls on the main street. Forty of them are identical general stores that sell identical merchandise at identical prices. Forty of them are identical fruit and vegetable stands that sell identical fruits and vegetables at identical prices. The remaining twenty are identical used clothing shops selling identical used clothing at remarkably identical prices. It defies all odds that hundreds of Los Angeles Kings t-shirts (celebrating the season of 1992) all managed to find their way to the same rural Ethiopian village. So we turned our attention to what was available in one of the general stores. Matching his and hers one-dollar flip flops? Too traditional. A plastic water jug? Too practical. A bar of soap? A can of tinned pineapple? Egyptian chewing gum? A pack of matches?

In the end we sorted through our collection of exotic foods imported from Addis Ababa and selected a nice bottle of wine. Then, with much fanfare, we departed the compound dressed in our finest clothes, carrying our gift and a wedding card tastefully made with purple hi-liter on a scrap piece of paper. The mood was festive.

We found Yohannes, the groom standing under the obligatory “I’m having a wedding!” wooden pole displaying the Ethiopian national flag they raise wherever there is a wedding celebration. He is inspecting a fenced off party area near a cluster of mud walled huts. He greeted us warmly and directed us to a hut on the top of a nearby hill where we gathered under the shade of a large acacia tree. After shouting a few parting instructions Yohannes wandered away. After a few minutes two young women and a girl emerged from the hut. They set up a small wooden table, and ceremoniously presented a festive platter of popcorn. Shortly thereafter we were joined by a noisy flock of hungry chickens who jockeyed for position hoping to catch any errant kernels. A curious donkey joined the circle peppering the human’s conversation with his own full-throated brays. Then a stray dog slinked around the tree, hungrily eyeing the chickens.

We found Yohannes, the groom standing under the obligatory “I’m having a wedding!” wooden pole displaying the Ethiopian national flag they raise wherever there is a wedding celebration. He is inspecting a fenced off party area near a cluster of mud walled huts. He greeted us warmly and directed us to a hut on the top of a nearby hill where we gathered under the shade of a large acacia tree. After shouting a few parting instructions Yohannes wandered away. After a few minutes two young women and a girl emerged from the hut. They set up a small wooden table, and ceremoniously presented a festive platter of popcorn. Shortly thereafter we were joined by a noisy flock of hungry chickens who jockeyed for position hoping to catch any errant kernels. A curious donkey joined the circle peppering the human’s conversation with his own full-throated brays. Then a stray dog slinked around the tree, hungrily eyeing the chickens.

The women set to work on the elaborate ritual of brewing coffee. The coffee ceremony is a unique Ethiopian phenomena. It begins with raw beans and cold charcoal, and ends a long time later with tiny cups of thick, syrupy, remarkably grainy coffee. No automatic coffee grinder is used in the procedure.

While the coffee was brewed, we were joined by the happy comings and goings of various well-wishers, friends and relatives the groom, and representatives from the local church. Dishes of delicious stewed goat meat were passed around the circle washed down with large glasses of the ubiquitous tella an Ethiopian home brew made from fermented sorghum. In the midst of this festivity I spoke with the women who were preparing the coffee, and discovered that they were not Yohannes’ kin folk or even personal friends They were village women who happened to live on top of the hill. I was left with the distinct impression that they hadn’t planned on hosting two ferenjes and a large group of wedding crashers that particular afternoon. But they didn’t seem too bothered by it either.

In the fenced off area by the flagpole a large number of well wishers had gathered. Judging by the barrels of tella, it was shaping up to be some party. I was just tipping back my third tall glass of tella when someone announced it was time to leave. “We’re going so soon?” I asked. “Yes of course! Yohannes has to get his wife!”

At that point, the drumming began — deep, pounding, infectious African drum beats. In the center of the large group of people, surrounded by drummers, stood Yohannes , wearing a crisp black suit, his head bowed before the white robed Church elders. Around him people clapped and danced in a circle. We were quickly swallowed up in the swaying, clapping, marching mass of humanity. As the priests continued their ritual blessings, the rhythm of the drums picked up intensity and the dancers reached a fever pitch. The women threw back their heads, opened their mouths, and let out a series of throaty, ear piercing screams. Unless you’ve heard someone ululate it’s difficult to describe, and even harder to forget.

Amidst the cacophony of pounding of drums, singing, clapping, ululations, and honking horns, our group which now numbered at least 60 persons, moved toward the two dilapidated mini-buses that waited to transport us to find Yohannes’s bride.

Amidst the cacophony of pounding of drums, singing, clapping, ululations, and honking horns, our group which now numbered at least 60 persons, moved toward the two dilapidated mini-buses that waited to transport us to find Yohannes’s bride.

Each mini-bus can comfortably sit eight to twelve persons. With tremendous fanfare everyone crammed into the buses, fifteen people inside each one, another fifteen sitting on the roof, clinging to the hood, or standing on the back bumper. Many of the passengers pounded their drums, and the others ululated. The road, a dusty obstacle course of rocks and craters, teemed with children, chickens, goats, tractors (without brakes), donkeys and cows. The drivers proceeded very slowly, the buses swaying from side to side. Accompanied by singing clapping and drum beats, we inched our way through the center of town towards the home of Yohannes’ bride.

We were greeted by at least 150 more people, who rushed out of the fenced off party area and stormed the vehicles. They had even bigger drums, clapped louder, and ululated with even more vigor. The groom was pushed into this sea of humanity. As is the custom, he was then required to dance for the in-laws in order to gain entry.

You didn’t have to speak Amharic to recognize that Yohannes wasn’t considered to be a good dancer, but with good-natured laughter and cheers the in-laws welcomed the clumsy groom and his friends into the compound. Although the bride was still nowhere to be seen, the wedding party had definitely started.

We all crammed into what was a pen for cattle and goats, now a hastily constructed into a shelter of logs with a pole roofing frame that supported a series of dilapidated tarps. A lot of straw was strewn on the ground and it smelled like a petting zoo. A number of wooden tables were adorned with pots of food; there were about 100 plastic lawn chairs, a cheap stereo, two small areas cordoned off with thin sheeting suspended on twine to indicate the VIP dining section, and a small mud walled tukul where the bride was apparantly hiding. Within these confines people danced or sat. Others watched the church elders practice a ceremonial rite.

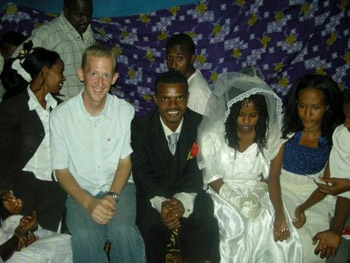

The church elders gave a blessing to the gifts that Yohannes had brought for his bride: a wedding dress, some jewelry, and a bottle of perfume. The elders and Yohannes’s father then prostrated themselves in front of the bride’s parents and engaged in a ritual in which they ask for acceptance. The bride’s family and friends responded with a volley of cheers and ululations. Then the groom’s friends and family responded with cheers and ululations of their own. Then there was a grand procession. The groom marched to the front door of the mud walled tukul, and offered his gifts through the open door. Custom dictates that the bride, if she accepts the gifts, must then put on the dress and come out. I remarked to the Ethiopian beside me, that back home in Canada, I’ve never heard of a bride getting dressed for her wedding in anything less than three hours, although in Canada the bride doesn’t have a hundred drunken revelers waiting impatiently outside her dressing room door. Yohannes’s bride was ready in ten minutes, glorious in a traditional satin bridal gown and veil.

Then it was time for the wedding feast. My friends and I were served first. Everything was chaos. You must first wait for a mass of people to accumulate around you. If one of the men carrying pots of food spots your group, they instruct you to sit in a circle and eat whether you want to or not even if you have already eaten five or six times.

Then it was time for the wedding feast. My friends and I were served first. Everything was chaos. You must first wait for a mass of people to accumulate around you. If one of the men carrying pots of food spots your group, they instruct you to sit in a circle and eat whether you want to or not even if you have already eaten five or six times.

Ethiopian food is delicious. Every meal begins with injera – a thin bubbly pancake with a slightly sour taste, made from sorghum or tef. The injera is laid flat on a giant plate in the center of the table. Flavourful stews and sauces are heaped on top. You tear off a portion of injera and use it to mop up the sauces and carry the meat to your mouth. This meal was accompanied by copious amounts of the thick brown fermented tella, stored in giant open barrels and served in tin cans. By using recycled tin cans for cups you never have to worry about setting your glass down and confusing it with someone else’s. “This 28 oz can of tomato paste? Oh yes, that’s my cup. Thanks. This tin of tuna must belong to you.”

The party continued well into the night. The wedding was so much fun that I suggested we should do another soon. We’ve done Id, Ethiopian Christmas, European New Years and Epiphany. It seems that the good people of Abdurafi can always find a reason to celebrate.

More Information:

Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) has been working in Abdurafi, Ethiopia, since 2003. The medical humanitarian organization provides treatment in Abdurafi for the neglected disease Kala Azar, as well as for HIV/AIDS and malnutrition. The hospital focuses on caring for those in surrounding agricultural areas, particularly seasonal migrant workers and settlers. For more information please visit: www.msf.ca.

Lonely Planet: Ethiopia

Ethiopian history

Tours Now Available in Ethiopia’s Amhara Region:

Simien Mountains National Park: Full-Day Hiking Tour

From Gondar: 2-Night 3-Day Simien National Park Trek

7 Days Trek in Simien Mountains

About the author:

Richard Currie was born in Toronto, and attended university in Kingston, Ontario. Upon graduating from medical school he moved to British Columbia to pursue training in rural family medicine and international health. He has previously worked in Kenya, Vietnam and Ghana. Currently he lives and works in Abdurafi, Ethiopia, on a nine month contract with Medecins Sans Frontieres.

Contact: richardcurrie@gmail.com

Photographs:

All photos are by Richard Currie.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.