by Keith Kellett

We didn’t stay long in Barcelona. Our cruise ship arrived at 1:00 pm, and were due to sail at 6:00 pm, so we weren’t allowed much time ashore. Nevertheless, eight tours were on offer and, since we hadn’t been to Barcelona before, we chose the ‘Tour of Barcelona’.

Since Barcelona is the second largest city in Spain, there was a lot of ground to cover and, as we crossed the city to climb the Montjuic Hill, I did wonder if the only remembrance I would have of the place was shaky video taken through the bus window.

The coach got caught in a traffic jam several times, and on two occasions, we stopped by a rather quirky, distinctive apartment block. ‘These are blocks of flats designed by Gaudi!’ announced the guide. This was the first I’d ever heard of him, but since then, I’ve come across his name and pictures of his work several times in my reading.

Certainly the buildings were different. Nature, it is said, abhors a straight line. So did Gaudi; the builders, glaziers and carpenters of Barcelona must have hated him. But, we didn’t stop at either of them. We were on our way to the Güell Park, where some of the best of Gaudi’s work is to be seen. Indeed, Gaudi used to live here, in a pink, fairy-tale house which is now the Gaudi Museum.

Certainly the buildings were different. Nature, it is said, abhors a straight line. So did Gaudi; the builders, glaziers and carpenters of Barcelona must have hated him. But, we didn’t stop at either of them. We were on our way to the Güell Park, where some of the best of Gaudi’s work is to be seen. Indeed, Gaudi used to live here, in a pink, fairy-tale house which is now the Gaudi Museum.

Antoni Gaudi was born in the province of Tarragona, in southern Catalonia on 25th June 1852. There’s some doubt about his actual place of birth; indeed, also about his name. It’s sometimes given as the Castilian ‘Antonio’, although the Catalan ‘Antoni’ is preferred.

But, wherever he was born, he spent most of his life in Barcelona, which has claimed him as its own. He studied architecture at Barcelona’s Escola Tècnica Superior d’Arquitectura, and soon began to leave his mark on the city. One of his early works were the lamp-posts in the Plaça Reial. Early in his career, he met the rich industrialist, the Condé Eusebi Güell, who was one of his main sponsors and supporters throughout his career.

Güell wanted to build a model village, on the lines of similar villages in England, such as George Cadbury’s Bourneville, in the Midlands. But, Cadbury built his village for workers in his chocolate factory. Güell was much more ambitious. He intended his village for the more affluent and influential people of Barcelona.

Güell wanted to build a model village, on the lines of similar villages in England, such as George Cadbury’s Bourneville, in the Midlands. But, Cadbury built his village for workers in his chocolate factory. Güell was much more ambitious. He intended his village for the more affluent and influential people of Barcelona.

The idea only barely took off, though, because the area was too far from Barcelona, and not served by public transport. But, a couple of Gaudi-designed houses were built. He also designed the distinctive aqueduct, which, usually hung with flowers, runs right through the park. Gaudi also designed the plaça decorated with broken tiles around the walls. He was also responsible for the seats and benches here; they’re especially engineered to dry out quickly after rain, and were reputedly based on a moulding of a woman’s buttocks, for maximum comfort.

From the plaça, there’s an excellent view of the city, with several tall cranes punctuating the skyline. They’re not all in the harbour; some are around another Gaudi project, the church of the Sagrada Familia (Holy Family). They’re not renovating it, though. Although it was started as far back as 1882 … it’s not completed yet. It’s only within the last year that it was consecrated as a basilica by the Pope.

Gaudi was a devout Catholic, and, in his later years, made the building of the Sagrada Familia his life’s work. However, Barcelona already had a perfectly good Cathedral, and this could have been the reason that no money at all came from the Church. The building was founded solely by public subscription. So, construction progressed very slowly.

Gaudi was a devout Catholic, and, in his later years, made the building of the Sagrada Familia his life’s work. However, Barcelona already had a perfectly good Cathedral, and this could have been the reason that no money at all came from the Church. The building was founded solely by public subscription. So, construction progressed very slowly.

Once, when this was mentioned, Gaudi is alleged to have said ‘My client is in no hurry’, which may have given rise to his nickname, ‘God’s architect’

Early in the 20th Century, work at the Güell Park slowly ceased, and, at some stage, Gaudi left his sugar-candy house, and went to live in the crypt of the Sagrada Familia. He lived the life of an obsessive recluse until, in 1926, when he was knocked down in the street by a tram. At first, he wasn’t recognised, and taken to the pauper’s hospital.

When his friends found him the next day, he refused to be moved, saying ‘I belong here, among the poor!’ Three days later, he died, and is buried in the crypt of his beloved Sagrada Familia. In the following years, construction almost stopped; first the Depression, then the Spanish Civil War and the years of the Franco regime accounted for funding draining to almost nothing. However, it has now recommenced, and it is hoped that it will be finished by 2026 … 100 years after its designer’s death.

Private Full Day Gaudi Tour: Pedrera Casa Batllo Sagrada Familia and Guell

If You Go:

Barcelona Airport is located 10 km (6.2 miles) southwest of the city. It mainly serves domestic, European and North African destinations, but does occasionally accept flights from South East Asia, and the Americas.

Most long-haul visitors will, therefore, usually come via Madrid. The air shuttle service from there was the world’s busiest route until 2008, when a high-speed rail line was opened, covering the distance between the two cities in 2 hours 40 minutes. www.renfe.com

Barcelona is also reachable by inter-city bus. The trip takes about 8 hours and costs about €30 single from Madrid; discounts are available for early booking and for group travel.

It stands at the junction of motorways from Zaragosa, Valencia and Perpignan (France) and is a popular call for cruise ships.

For much more information about Gaudi’s work, I recommend ‘Gaudí by Maria Antonietta Crippa, ISBN 978-3-8228-2518-1

About the author:

Having written as a hobby for many years while serving in the Royal Air Force, Keith Kellett saw no reason to discontinue his hobby when he retired. With time on his hands, he produced more work, and found, to his surprise, it ‘grew and grew’ and was good enough to finance his other hobbies; travelling, photography and computers. He is trying hard to prevent it from becoming a full-time job! He has published in many UK and overseas print magazines, and on the Web. He is presently trying to get his head around blogging, podcasting and video.

All photos are by Keith Kellett.

When we went to Notre Dame, I was delighted to find the Hotel Dieu next door. Why? This was one of the first hospitals built in Europe, in 622 AD. I assumed not many travelers knew it was a hospital and passed by thinking it was a hotel. (It says, “Hotel Dieu” at the entrance and is decorated with international flags.) The present building was not the one from 622 AD, as that original one was burned down in the 1700s. The one we see today was built in 1822. Why is it still called a hotel? In French, it translates to Hostel of God. The first European hospitals during the Middle Ages were managed by the clergy. Their purpose initially was not to treat the sick but to serve as lodging to travelers.

When we went to Notre Dame, I was delighted to find the Hotel Dieu next door. Why? This was one of the first hospitals built in Europe, in 622 AD. I assumed not many travelers knew it was a hospital and passed by thinking it was a hotel. (It says, “Hotel Dieu” at the entrance and is decorated with international flags.) The present building was not the one from 622 AD, as that original one was burned down in the 1700s. The one we see today was built in 1822. Why is it still called a hotel? In French, it translates to Hostel of God. The first European hospitals during the Middle Ages were managed by the clergy. Their purpose initially was not to treat the sick but to serve as lodging to travelers. This military museum houses historical artifacts of armour, artillery, and various weapons through French history. Napoleon’s Tomb is situated at one end where you have to leave the museum building to walk to the building’s tomb. We were certainly not military experts nor were we that interested in the museum (as we had planned on just going to Napoleon’s Tomb at the end of the tour), but a couple of amusing gems popped up here. We saw hundreds of knit armor and noticed some really small ones that would fit a child. Did children have to participate in the wars as well? Child labor laws did only appear recently in time! After passing by several cannons on our way to the tomb, we found a cannon with figures of two pairs of kissing couples [TOP PHOTO]. We could not find any history panels to explain its origin. Did the cannon makers have a sense of humor to make love and not war?

This military museum houses historical artifacts of armour, artillery, and various weapons through French history. Napoleon’s Tomb is situated at one end where you have to leave the museum building to walk to the building’s tomb. We were certainly not military experts nor were we that interested in the museum (as we had planned on just going to Napoleon’s Tomb at the end of the tour), but a couple of amusing gems popped up here. We saw hundreds of knit armor and noticed some really small ones that would fit a child. Did children have to participate in the wars as well? Child labor laws did only appear recently in time! After passing by several cannons on our way to the tomb, we found a cannon with figures of two pairs of kissing couples [TOP PHOTO]. We could not find any history panels to explain its origin. Did the cannon makers have a sense of humor to make love and not war? The Rodin Museum houses the famed sculptor’s best works; he requested the government to establish a museum for his artwork. But what you might have known is that Rodin’s mistress, sculptor Camille Claudel, also has a collection here. Rodin and Claudel had a fiery on-and-off relationship; she once accused him of stealing her sculpting ideas. After Rodin left her to return to Rose Beuret, his longtime companion and mother of his son, Claudel spiraled into mental illness, living in a mental institution the last years of her life. Rodin, perhaps having a soft heart and appreciating her talents, requested Claudel’s works to be showcased in his museum.

The Rodin Museum houses the famed sculptor’s best works; he requested the government to establish a museum for his artwork. But what you might have known is that Rodin’s mistress, sculptor Camille Claudel, also has a collection here. Rodin and Claudel had a fiery on-and-off relationship; she once accused him of stealing her sculpting ideas. After Rodin left her to return to Rose Beuret, his longtime companion and mother of his son, Claudel spiraled into mental illness, living in a mental institution the last years of her life. Rodin, perhaps having a soft heart and appreciating her talents, requested Claudel’s works to be showcased in his museum.

Before our adoption journey began, I knew next to nothing about Kazakhstan, in part, because until 1991, the country had been swallowed up in that vast entity known as the Soviet Union. So swallowed, it had lost its name, its freedom, much of its language and very nearly, everything about it which made it distinctly Kazakh. Even today, driving the streets of Karaganda, one notices the crouching, well-worn blocks of Soviet style apartment buildings with their Soviet graphics and wonders at the statue of Lenin still posing in the center of town. Still, there are no statues of Stalin, and that is a comfort. After all, it was Stalin who used Karaganda; along with hundreds of other locations in the vast Asian and Siberia steppes, as a full-service slave labor camp, a part of his infamous Gulag system. For years, people were deported to Kazakhstan from places as far away as Germany, Poland, Korea and Japan, put to work in the coal mines still prevalent in the area today and kept behind fences studded with barbed wire, guard towers and patrolled by guard dogs. Alexander Solzhenitsyn; the famous Russian author and Gulag inmate, was set to work not far from Karaganda in Ekibastuz, Kazakhstan. His famous novel, “ One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”, was based on his experiences as a prisoner there.

Before our adoption journey began, I knew next to nothing about Kazakhstan, in part, because until 1991, the country had been swallowed up in that vast entity known as the Soviet Union. So swallowed, it had lost its name, its freedom, much of its language and very nearly, everything about it which made it distinctly Kazakh. Even today, driving the streets of Karaganda, one notices the crouching, well-worn blocks of Soviet style apartment buildings with their Soviet graphics and wonders at the statue of Lenin still posing in the center of town. Still, there are no statues of Stalin, and that is a comfort. After all, it was Stalin who used Karaganda; along with hundreds of other locations in the vast Asian and Siberia steppes, as a full-service slave labor camp, a part of his infamous Gulag system. For years, people were deported to Kazakhstan from places as far away as Germany, Poland, Korea and Japan, put to work in the coal mines still prevalent in the area today and kept behind fences studded with barbed wire, guard towers and patrolled by guard dogs. Alexander Solzhenitsyn; the famous Russian author and Gulag inmate, was set to work not far from Karaganda in Ekibastuz, Kazakhstan. His famous novel, “ One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”, was based on his experiences as a prisoner there. Though economic times are tough, there is a new openness to Karaganda. We met people, from translators to drivers, to those working in the orphanages we visited, who were willing to discuss the painful past of their city, its history of Soviet oppression and to ask us in turn, about our experiences in the west. No attempt was made to hide the shoddiness of much of their surroundings nor were they too proud to ask for help, especially as it pertained to my husband and I buying much needed supplies for our daughter’s orphanage. We found the younger adults and children particularly interested in our lives, our language and why were had come so far to their city. Indeed, it was the older generation of residents who kept their distance and watched us warily when we walked past or played outside with our new daughter. Perhaps a life spent under the thumb of a communist regime had taught them to be more cautious.

Though economic times are tough, there is a new openness to Karaganda. We met people, from translators to drivers, to those working in the orphanages we visited, who were willing to discuss the painful past of their city, its history of Soviet oppression and to ask us in turn, about our experiences in the west. No attempt was made to hide the shoddiness of much of their surroundings nor were they too proud to ask for help, especially as it pertained to my husband and I buying much needed supplies for our daughter’s orphanage. We found the younger adults and children particularly interested in our lives, our language and why were had come so far to their city. Indeed, it was the older generation of residents who kept their distance and watched us warily when we walked past or played outside with our new daughter. Perhaps a life spent under the thumb of a communist regime had taught them to be more cautious.

For those wishing to visit Karaganda, hotels, restaurants and apartments are available, in various price and quality ranges. While in Karaganda, my husband and I stayed in an apartment whose previous owners had emigrated to Israel, leaving the apartment, along with their clothes, family pictures and clothing, behind. Many permanent residents will move in with relatives and rent their apartments to foreigners willing to pay well and keep their apartments clean. The price for such an apartment is still reasonable and is a great way to get to know the people, places and culture of the city. Karaganda boasts a nice lake and central park in its downtown area which is a welcome change from the traffic of the streets and during the summer, a large circus plays in town which is an event the entire city looks forward to. Karaganda also supports a university and various academic institutions. There are gardens, a water park, a theater and a museum which contains many interesting displays on traditional Kazakh nomadic life which we found very well done. We also enjoyed the many monuments dotting the city, especially the massive memorial dedicated to the Kazakh effort during World War II.

For those wishing to visit Karaganda, hotels, restaurants and apartments are available, in various price and quality ranges. While in Karaganda, my husband and I stayed in an apartment whose previous owners had emigrated to Israel, leaving the apartment, along with their clothes, family pictures and clothing, behind. Many permanent residents will move in with relatives and rent their apartments to foreigners willing to pay well and keep their apartments clean. The price for such an apartment is still reasonable and is a great way to get to know the people, places and culture of the city. Karaganda boasts a nice lake and central park in its downtown area which is a welcome change from the traffic of the streets and during the summer, a large circus plays in town which is an event the entire city looks forward to. Karaganda also supports a university and various academic institutions. There are gardens, a water park, a theater and a museum which contains many interesting displays on traditional Kazakh nomadic life which we found very well done. We also enjoyed the many monuments dotting the city, especially the massive memorial dedicated to the Kazakh effort during World War II.

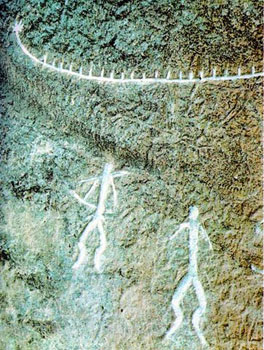

Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Gobustan contains unique rock art engravings and images depicting the lifestyle, culture, economy, world outlook, magic and totemic conception, customs and traditions of the ancient inhabitants of the area. Long time ago the sea waves licked these mountains and then abandoned them leaving characteristic relief traces on the polished rocks.

Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Gobustan contains unique rock art engravings and images depicting the lifestyle, culture, economy, world outlook, magic and totemic conception, customs and traditions of the ancient inhabitants of the area. Long time ago the sea waves licked these mountains and then abandoned them leaving characteristic relief traces on the polished rocks.

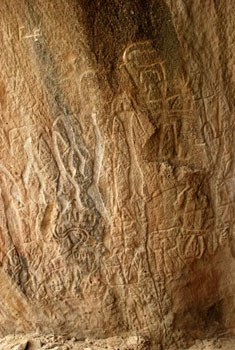

Gobustan rock carvings are marked with thematic diversity, plot originality, and certain artistic skill. Most of the petroglyphs depict people, domestic and wild animals, such as oxen, goats, gazelles, deer, horses, birds, fish, as well as battle scenes, ritual dances, bullfights, boats with men, hunting, fishing, solar symbols, etc.

Gobustan rock carvings are marked with thematic diversity, plot originality, and certain artistic skill. Most of the petroglyphs depict people, domestic and wild animals, such as oxen, goats, gazelles, deer, horses, birds, fish, as well as battle scenes, ritual dances, bullfights, boats with men, hunting, fishing, solar symbols, etc.

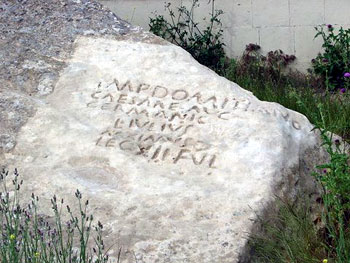

Personally, I am not sure about the presence of the Vikings in these areas. But the Romans were for sure. A rock found in Gobustan contains a Roman inscription which proves the presence of a centurion of the XII (12th) Roman legion, known as the Fulminat (Lightning) here on the shore of the Caspian Sea during the reign of Emperor Titus Flavius Domitianus in the second half the 1st century AD. Some assume, this may be the easternmost point any Roman patrol even ventured to. I can read the inscription though I am not good in Latin: “IMP DOMITIANO CAESARE AVG GERMANIC LIVIVS MAXIMVS LEG XII FVL” (“Emperor Domitian, the Blessed Caesar Germanicus. Livius Maximus, Legio XII Fulminata”).

Personally, I am not sure about the presence of the Vikings in these areas. But the Romans were for sure. A rock found in Gobustan contains a Roman inscription which proves the presence of a centurion of the XII (12th) Roman legion, known as the Fulminat (Lightning) here on the shore of the Caspian Sea during the reign of Emperor Titus Flavius Domitianus in the second half the 1st century AD. Some assume, this may be the easternmost point any Roman patrol even ventured to. I can read the inscription though I am not good in Latin: “IMP DOMITIANO CAESARE AVG GERMANIC LIVIVS MAXIMVS LEG XII FVL” (“Emperor Domitian, the Blessed Caesar Germanicus. Livius Maximus, Legio XII Fulminata”). Near the end of our trip I ask my brother whether he would like to see the “Gobustan kitchen”. He first think I am joking. But I am not. I take him to the place I have read about many times and show him the bowl-shaped depressions carved out in the rock. They were probably used for collecting rainwater, the blood of sacrificed animals or for cooking. I remember from the old people that until quite recently mountain shepherds used these “bowls” for boiling milk by dropping heated stones into them. It may be an explanation about the usage of similar “bowls” by the prehistoric people.

Near the end of our trip I ask my brother whether he would like to see the “Gobustan kitchen”. He first think I am joking. But I am not. I take him to the place I have read about many times and show him the bowl-shaped depressions carved out in the rock. They were probably used for collecting rainwater, the blood of sacrificed animals or for cooking. I remember from the old people that until quite recently mountain shepherds used these “bowls” for boiling milk by dropping heated stones into them. It may be an explanation about the usage of similar “bowls” by the prehistoric people.