by Melanie Harless

In my junior year at Central High School in Fountain City, Tennessee, a mock funeral was held for our town, which at the time was said to be the largest unincorporated city in the country with approximately 30,000 residents. After much resistance to annexation into the city of Knoxville from the time they began proposing our annexation in 1959, the town reluctantly gave in to becoming a part of Knoxville. On February 12, 1962, six pallbearers appropriately dressed in black and Abe Lincoln stove pipe hats carried a casket for the mock funeral service down Broadway. About 350 mourners, some carrying signs with slogans such as “Died in 1962—we lived in peace” and “Surrendered with Reluctance,” followed the hearse. The Central High School band accompanied the procession playing the solemn march “Pomp and Circumstance.”

I did not attend Fountain City’s funeral, but a friend told me about it later and said it was quite an event that ended with the playing of “Taps.” Actually, as a teenager, I didn’t notice much difference after we were annexed, except that we got street lights on our street, which was a positive effect to me. I lived in Fountain City from the time I was nine until I got married and left, so I consider it my hometown. This trip was a sentimental journey for me.

I did not attend Fountain City’s funeral, but a friend told me about it later and said it was quite an event that ended with the playing of “Taps.” Actually, as a teenager, I didn’t notice much difference after we were annexed, except that we got street lights on our street, which was a positive effect to me. I lived in Fountain City from the time I was nine until I got married and left, so I consider it my hometown. This trip was a sentimental journey for me.

I first went back to my old high school, which is no longer a high school, but became Gresham Middle School when a new Central High was built in 1971. I am very glad I was able to attend at the old location. It is a lovely old building and campus. Prior to becoming Central High School in 1906, the campus was a college called Holbrook Normal School which had been established in l893.

We then drove down Hotel Avenue to the Fountain City Art Center at 213 Hotel Avenue.

I remembered when I lived there that the building was home to the Fountain City Library. The Center was in-between main exhibits when we were there, but two new exhibits are now on display. The Knoxville Book Arts Guild and the Southern Appalachian Photography Society will be on view until April 8. Student exhibits from different area schools are also exhibited in the Center. There were some excellent works from middle school students on display when we were there.

I remembered when I lived there that the building was home to the Fountain City Library. The Center was in-between main exhibits when we were there, but two new exhibits are now on display. The Knoxville Book Arts Guild and the Southern Appalachian Photography Society will be on view until April 8. Student exhibits from different area schools are also exhibited in the Center. There were some excellent works from middle school students on display when we were there.

Also located inside the Art Center is the Parkside Open Door Gallery with original art and crafts by local artists which are available for purchase. The hours for the Art Center are Tuesday and Thursday 9 am to 5 pm, Wednesday and Friday 10 am to 5 pm, and Saturday 9 am to 1 pm.

The Art Center is located next to Fountain City Park. My memories of this park go back to early childhood as a place where we had family reunions and picnics. Though the park was officially established in 1932, in researching, I found that it was used for religious camp meetings at least as early as the 1830s. Union veterans of the Civil War were also known to use the park for reunions.

The eight-acre park now has lots of colorful playground equipment in addition to the swings and slides that were there when I was a youngster. Unlike some playgrounds, it seems to get a lot of use during good weather. The park is also now circled by a paved walking path, with freestanding “porch swings” scattered along the trail where you can sit and rest and watch the people and look at the old trees and the natural spring which flows through the park into First Creek. Fountain City Park is not owned by the City of Knoxville, but is owned, operated and maintained by the Fountain City Lion’s Club. The Lion’s Club Building is in the park and can be rented for meetings. My late father was a member of the club and we held his eightieth birthday party there.

The eight-acre park now has lots of colorful playground equipment in addition to the swings and slides that were there when I was a youngster. Unlike some playgrounds, it seems to get a lot of use during good weather. The park is also now circled by a paved walking path, with freestanding “porch swings” scattered along the trail where you can sit and rest and watch the people and look at the old trees and the natural spring which flows through the park into First Creek. Fountain City Park is not owned by the City of Knoxville, but is owned, operated and maintained by the Fountain City Lion’s Club. The Lion’s Club Building is in the park and can be rented for meetings. My late father was a member of the club and we held his eightieth birthday party there.

After walking around the park path, which is called the Fountain City Greenway, we walked across Hotel Avenue to the Creamery Park Grille. The Creamery is in an historic building with interesting décor. We were seated upstairs by the window and had a good view of the park. The food was quite good, but we decided to forgo dessert there and drive across Broadway to 2803 Essary Drive later to have our dessert at Litton’s Restaurant & Market, which is famous for its desserts and hamburgers. Litton’s started out in 1946 as a market and service station in the Inskip community of Fountain City. In 1980, Barry Litton, grandson of the original owner, opened Litton’s Market. In 1983, Litton’s Market and Restaurant was born, and in the same year they opened their bakery. In the 1990s, Litton’s became a Fountain City landmark and is consistently voted East Tennessee’s Best year after year for their burgers and desserts. They have been featured on ESPN and in Southern Living Magazine. We shared the coconut cream pie at the restaurant and brought a piece of German chocolate cake home to share later. Both were out of this world. The turtle brownies and Italian cream cake, which I have had in the past, are also delicious. A visit to Litton’s is a must do, but they are closed on Sundays. They are open Monday to Thursday 11 am to 8 pm, Friday and Saturday, 11 am to 10 pm.

Before going to Litton’s, we walked around the block of Hotel Avenue and crossed the street to Fountain City Lake, also known as the duck pond. The lake was constructed around 1890. Designed by civil engineer F.G. Phillips, the heart-shaped body of water features a large fountain in the center gushing water skyward. We walked all around the lake, being careful to watch where we stepped. There were families there feeding the ducks, young couples and older couples strolling around, and even a couple of men fishing, and lots and lots of ducks.

Before going to Litton’s, we walked around the block of Hotel Avenue and crossed the street to Fountain City Lake, also known as the duck pond. The lake was constructed around 1890. Designed by civil engineer F.G. Phillips, the heart-shaped body of water features a large fountain in the center gushing water skyward. We walked all around the lake, being careful to watch where we stepped. There were families there feeding the ducks, young couples and older couples strolling around, and even a couple of men fishing, and lots and lots of ducks.

Fountain City was established in 1788 by John Adair, a Revolutionary War veteran and was originally known as Adair Fort. It was used as a depot for protecting emigrant families traveling west to settle in what is now Nashville. Fountain City still maintains historical pride with signs and markers that tell of the former town’s history. Now a part of North Knoxville, the town of Fountain City is gone, but there is still that small town feeling and sense of community. I’ve noticed that most people who live there say they live in Fountain City, not Knoxville. And I, too, am gone from Fountain City, but it will always be my hometown.

Chef’s Table Tour in Downtown Knoxville

If You Go:

Fountain City is a neighborhood in northern Knoxville, Tennessee in the southeast United States. The main road in Fountain City is Broadway, a section of U.S. Hwy 441, which connects it to downtown Knoxville to the south. Interstate 640 passes along Fountain City’s southern boundary, and I 75 passes through the western part of the community. Travelers to the area will also want to visit Gatlinburg, TN which is only an hour’s drive away.

Day Tour: Moonshine and Wine Tasting from Gatlinburg

About the author:

Melanie Harless writes a column on regional travel for a local news-magazine. In addition to travel writing, she writes memoir-essays, poetry, and short stories. She also does photography. Her work has been published in anthologies, online and print magazines and newspapers. This is her fourth contribution to Travel Thru History.

All photos are by Melanie Harless.

Crowding into our seats, old wooden benches polished and stained as if new, we wait for the jolt of the engine rejoining us. There are no CDs or TV screens to entertain us on the long haul but we have our tour group leader, brakeman and jack-of-all-trades, John, to keep us informed over the course of the 2.5 hour round trip.

Crowding into our seats, old wooden benches polished and stained as if new, we wait for the jolt of the engine rejoining us. There are no CDs or TV screens to entertain us on the long haul but we have our tour group leader, brakeman and jack-of-all-trades, John, to keep us informed over the course of the 2.5 hour round trip. Up from the full forests of the valley through increasingly stunted and twisted growth and into the struggling bushes of the broad mountain slope we rise. The engine chugs behind us eating coal and spitting black smoke in a long trail; straining to reach the next water stop. That pause gives us a chance to regard an old shed clinging to the mountain at a severe angle or so it seems. In fact the shed is perfectly horizontal, it is us who are off kilter.

Up from the full forests of the valley through increasingly stunted and twisted growth and into the struggling bushes of the broad mountain slope we rise. The engine chugs behind us eating coal and spitting black smoke in a long trail; straining to reach the next water stop. That pause gives us a chance to regard an old shed clinging to the mountain at a severe angle or so it seems. In fact the shed is perfectly horizontal, it is us who are off kilter. The summit rises temptingly before us but again we pause, this time for another engine easing its coach back down to the distant valley. As seems so natural its passengers wave to us and us to them, a shared commonality in the experience. Trust in the engine is tested as we back off our siding to resume the climb. The comforting forward pitch sets us back on course.

The summit rises temptingly before us but again we pause, this time for another engine easing its coach back down to the distant valley. As seems so natural its passengers wave to us and us to them, a shared commonality in the experience. Trust in the engine is tested as we back off our siding to resume the climb. The comforting forward pitch sets us back on course.

This summit is visited by a quarter million people a year and is seen by many in regular New England weather reports. Here winds have reached 231 miles an hour and the temperature dropped to -47 minus the wind factor. This September day was good with winds at 37 mph, gusting to 75. In winter it is a frost covered fairy land.

This summit is visited by a quarter million people a year and is seen by many in regular New England weather reports. Here winds have reached 231 miles an hour and the temperature dropped to -47 minus the wind factor. This September day was good with winds at 37 mph, gusting to 75. In winter it is a frost covered fairy land.

So, when I found out that the Museum of Making Music was about a stone’s throw from Legoland California Resort & Sea Life Aquarium in Carlsbad, I decided to make some time and check out the story on making music. A hidden jewel, it’s a treasure trove of a century of musical instruments and innovations that shaped American popular music.

So, when I found out that the Museum of Making Music was about a stone’s throw from Legoland California Resort & Sea Life Aquarium in Carlsbad, I decided to make some time and check out the story on making music. A hidden jewel, it’s a treasure trove of a century of musical instruments and innovations that shaped American popular music.

Along the way, I learned about someone I had never heard of as revolutionizing studio drumming. In the 1960’s, Hal Blaine developed a signature drum beat that made him quite popular with producers and songwriters. To keep up with the demand, he used a cartage company to transport his customized drums and hardware to meet the demands of live and studio performances. Songs like Elvis Presley’s “Return to Sender” and Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night” were recorded on the Hal Blaine Custom Drum Kit.

Along the way, I learned about someone I had never heard of as revolutionizing studio drumming. In the 1960’s, Hal Blaine developed a signature drum beat that made him quite popular with producers and songwriters. To keep up with the demand, he used a cartage company to transport his customized drums and hardware to meet the demands of live and studio performances. Songs like Elvis Presley’s “Return to Sender” and Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night” were recorded on the Hal Blaine Custom Drum Kit.

The 1970s brought about the Austin music scene as it is now. Recording artist Willie Nelson was prominent among the artists that helped bring it to life. PBS’s Austin City Limits show is the longest running live performance TV show in US history, and it produces a massive music festival there each September.

The 1970s brought about the Austin music scene as it is now. Recording artist Willie Nelson was prominent among the artists that helped bring it to life. PBS’s Austin City Limits show is the longest running live performance TV show in US history, and it produces a massive music festival there each September. Just a short walk from downtown over the Colorado River, the South Congress area is one of the most interesting in Austin. And with all the city has to offer, that’s saying something! We found ourselves returning there over and over to browse. Block after block is full of great vintage clothing stores, restaurants, and shops crammed full of folk art curios.

Just a short walk from downtown over the Colorado River, the South Congress area is one of the most interesting in Austin. And with all the city has to offer, that’s saying something! We found ourselves returning there over and over to browse. Block after block is full of great vintage clothing stores, restaurants, and shops crammed full of folk art curios. There’s a plethora of great stuff to see in the downtown core. Here are just five of our faves.

There’s a plethora of great stuff to see in the downtown core. Here are just five of our faves. In 1960, the Colorado River, which runs through the centre of Austin, was dammed to create a huge reservoir originally called Town Lake, recently renamed Lady Bird Lake in honour of celebrated Austin patron Lady Bird Johnson. There is a well-appointed trail (approx. 16 km, or 10 miles long) all around the lake, complete with pedestrian-only bridges at either end. A walk around it is a great remedy for the excesses of the night before in the local watering holes. Try and get an early start to avoid the mid-day heat.

In 1960, the Colorado River, which runs through the centre of Austin, was dammed to create a huge reservoir originally called Town Lake, recently renamed Lady Bird Lake in honour of celebrated Austin patron Lady Bird Johnson. There is a well-appointed trail (approx. 16 km, or 10 miles long) all around the lake, complete with pedestrian-only bridges at either end. A walk around it is a great remedy for the excesses of the night before in the local watering holes. Try and get an early start to avoid the mid-day heat.

Just a forty minute drive west of downtown Austin is the world-famous Collings Guitar Factory. We were expecting something a bit short and superficial, but were pleasantly surprised to discover it was an extremely comprehensive look at every phase of instrument building. The 90 minute journey took us from a climate-controlled warehouse full of blocks of exotic wood to the final room where the guitars, mandolins and so on were shipped out. There is only one tour a week, so it’s best to book ahead by phone or email.

Just a forty minute drive west of downtown Austin is the world-famous Collings Guitar Factory. We were expecting something a bit short and superficial, but were pleasantly surprised to discover it was an extremely comprehensive look at every phase of instrument building. The 90 minute journey took us from a climate-controlled warehouse full of blocks of exotic wood to the final room where the guitars, mandolins and so on were shipped out. There is only one tour a week, so it’s best to book ahead by phone or email.

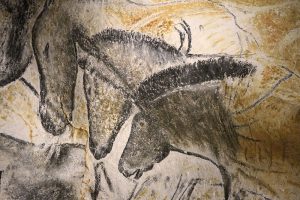

By 1680, the year of the Pueblo Revolt in New Mexico, horses spread rapidly through the plains and prairies of North America, probably reaching the Northwest around 1700. And the Nez Perce tribe, long known for their dog-breeding skills, quickly adapted to the horse, harnessing it as an invaluable aide in hunting buffalo. Because of the horse’s speed, they were able to cover more territory in less time and thus extend the expanse of their hunting grounds. Life was good and meat became more plentiful as a result.

By 1680, the year of the Pueblo Revolt in New Mexico, horses spread rapidly through the plains and prairies of North America, probably reaching the Northwest around 1700. And the Nez Perce tribe, long known for their dog-breeding skills, quickly adapted to the horse, harnessing it as an invaluable aide in hunting buffalo. Because of the horse’s speed, they were able to cover more territory in less time and thus extend the expanse of their hunting grounds. Life was good and meat became more plentiful as a result. Over the following years, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce found that his tribal homelands were increasingly encroached upon by white settlers, despite signed treaty promises to the contrary. Rather than continue to fight against overwhelming odds, he mustered a band of his people consisting of several warriors, elders, and many women and children, embarking on a 3-month, 1,170 mile journey to sanctuary in Canada.

Over the following years, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce found that his tribal homelands were increasingly encroached upon by white settlers, despite signed treaty promises to the contrary. Rather than continue to fight against overwhelming odds, he mustered a band of his people consisting of several warriors, elders, and many women and children, embarking on a 3-month, 1,170 mile journey to sanctuary in Canada. Nowadays, the Appaloosa horse breed is enjoying a resurgence in popularity and can often be seen exhibited at county fairs along with their young mounts. Besides being popular with young horse riders, Appaloosas are also used as working ranch horses and trail horses. The Appaloosa Horse Club, an international breed registry, has records of more than 635,000 Appaloosas and 33,000 members. The horses excel in many competitive events, including racing, jumping, dressage, reining roping gaming, pleasure and endurance.

Nowadays, the Appaloosa horse breed is enjoying a resurgence in popularity and can often be seen exhibited at county fairs along with their young mounts. Besides being popular with young horse riders, Appaloosas are also used as working ranch horses and trail horses. The Appaloosa Horse Club, an international breed registry, has records of more than 635,000 Appaloosas and 33,000 members. The horses excel in many competitive events, including racing, jumping, dressage, reining roping gaming, pleasure and endurance.