by Robert Hale

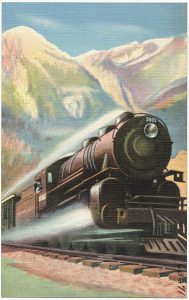

This is an interesting anniversary year. The US National Park Idea (America’s Best Idea) is 140 years old; Amtrak is 40 years old. They are connected!

Let’s go back to the summer of 1957 for a snippet of a conversation: “If it weren’t for the railroads you and I might be selling newspapers. Take a long look at that down there.”

That’s Jack, my boss at the Great Northern Railroad desk in Glacier Park Lodge. A summer passenger agent – me, holding down a three-month long job – is listening intently to a man who knows the story.

Slowly rolling past the Glacier Park east entrance is the Empire Builder, with its sparkling new Great Domes. The Builder doesn’t stop at the park. That’s the duty of its sister train, the Western Star. The Star is an equally sleek streamliner (but without the domes) that runs between Chicago, and Seattle and Portland.

Jack’s not smiling. “Take a long look. You’ll never see another new car on the Great Northern, or any other line. That’s the end of it. We might be selling newspapers yet!”

It all began when the Northern Pacific slammed down the last spike in 1882 and its trains started chugging passengers to Yellowstone. That event got the nation looking at itself – in person, first hand!

It all began when the Northern Pacific slammed down the last spike in 1882 and its trains started chugging passengers to Yellowstone. That event got the nation looking at itself – in person, first hand!

Early train travel was expensive. It was much like riding Amtrak today – beyond the budget of most Americans! But, that fit the plans of the railroads. The railroads knew that the more the wealthy rode, the quicker the fares could come down bringing more Americans to the rails. And to make sure that happened, the Northern Pacific went on an advertising campaign unlike anything seen before in the US and Europe. Magazine ads, newspaper ads, billboards and flyers – there wasn’t an advertising outlet the Northern Pacific missed. The NP could take travelers west to the parks and to the ocean.

The Northern Pacific saw potential profit from the vastness and emptiness of the Yellowstone area. To that end it not only promoted the geysers through advertising and word-of-mouth, it used every bit of political pressure it could muster to have the area declared a “national park.”

It is that “pressure” and the tactics employed by the railroad that moved Yellowstone’s late historian, Aubrey L. Haines, to excoriate the railroad. Heavy-handed, cajoling, threatening, exploiters, bad guys, devious, sly, cunning, Haines says of the NP.

But, one has to ask: “If not the railroad, then who?”

Haines then attacks the Northern Pacific for, “…the mundane purpose of making a profit, in this case by hauling tourists…” A profit…by hauling tourists. Hauling tourists, why the very thought of it…a really bad idea…almost evil! Mundane, indeed…But, a question: “If not a profit, than for what?”

There is one more evil characteristic of the railroad according to Haines: Monopoly! That’s been the operative word since the beginning of the railroads and the national parks. Hotels, buses, and service stations are each operated as a monopoly within the national parks…by law!

Make no mistake here; the Northern Pacific was in it all the way to make a profit – an idea that rankled historian Haines no end. What the motive of the railroad should have been he did not say.

For certain, along the way the NP manipulated, pressured, and buttonholed to get it’s way – and right-of-way – in Yellowstone. Business was, for good or evil, being conducted the way business was conducted in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The NP invited artist Thomas Moran to visit the area and to help promote it as a tourist destination. Moran’s paintings of the falls marked the “beginning of the beginning” for America’s National Parks.

The Northern Pacific’s exploration and development of Yellowstone moved other railroads to “sell” the vistas and wild spectacles along their rights-of-way. The Southern Pacific pushed hard for the establishment of Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant National Parks. General Grant was eventually absorbed into Kings Canyon National Park.

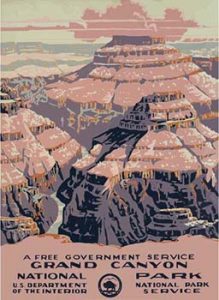

The Santa Fe railroad went “All the Way” to the Grand Canyon, where it built a luxury hotel and resort complex. The Union Pacific established itself on the opposite side of the canyon. The park facilities are still bringing in visitors by the thousands.

The Santa Fe railroad went “All the Way” to the Grand Canyon, where it built a luxury hotel and resort complex. The Union Pacific established itself on the opposite side of the canyon. The park facilities are still bringing in visitors by the thousands.

Eventually, Santa Fe, Union Pacific, Southern Pacific, Northern Pacific, Great Northern, Burlington, Milwaukee Road, Chicago and Northwestern, all had stops adjacent to, or relatively near various national parks.

In contrast to almost every other rail line, the Great Northern bought its own roadbed, not relying on federal government arrangements, as it laid down track to the west coast. In addition to hotels – in two countries, one must add – the Great Northern added several chalets along high mountain trails in Glacier Park to accommodate over-night hikers. Great Northern’s Western Star made two “front door” stops in Glacier National Park– East Glacier, and Belton on the western edge.

Taking a train to the national parks today is obviously not what it once was. Amtrak’s Empire Builder still makes the two Glacier Park stops. Amtrak will get you to Merced, California and then an Amtrak bus will transport you to Yosemite Valley. Amtrak’s Southwest Chief, a descendant of Santa Fe’s famous Chief and Super Chief trains, arrives in Williams, AZ where visitors can board the Grand Canyon Railway’s spiffy, shiny, and sleek service right to the rim! The latter is a daily excursion train – a delightful experience on a highly spruced up train. And that’s about it for train rides to the Parks!

So, while the famous delightful over-night experiences of comfy beds and pillows, expertly prepared meals, and the perfect pace for traveling are available on precious few Amtrak trains, the National Parks are still there, beckoning with their ageless wonders. And, if you plan it correctly, you can still fall asleep to the rhythm of the rails. So, Happy birthday National Park Service; Happy birthday Amtrak!

(Oh…and those newspapers Jack thought we might be selling… they’re in not doing so well either!)

If You Go:

Amtrak Train Travel Info: www.seat61.com/UnitedStates.htm

About the author:

Freelance writer, Bob Hale is a former Chicago radio and TV broadcaster. His college summers were spent in the passenger departments the Burlington Railroad in Chicago, and the Great Northern in Glacier National Park.

Photo credits:

Amtrak train and passengers by: National Archives at College Park / Public domain

Northern Pacific Montana poster illustration: Boston Public Library / Public domain

A ‘tall tale’ is one that exaggerates, and the Paul Bunyan tales are among the tallest. Paul was the imaginary hero of the strong men who felled trees, the lumberjacks of the North Woods of America. Tales told how he used whole pine trees to comb his grizzled hair and dark beard. The griddle for his pancakes was as large as Lake Bemidji (Minnesota), which resembles Paul’s giant footprint; lumberjacks greased it by skating over it with strips of bacon strapped to their feet. And it took two acres of brush fire to heat the griddle..

A ‘tall tale’ is one that exaggerates, and the Paul Bunyan tales are among the tallest. Paul was the imaginary hero of the strong men who felled trees, the lumberjacks of the North Woods of America. Tales told how he used whole pine trees to comb his grizzled hair and dark beard. The griddle for his pancakes was as large as Lake Bemidji (Minnesota), which resembles Paul’s giant footprint; lumberjacks greased it by skating over it with strips of bacon strapped to their feet. And it took two acres of brush fire to heat the griddle.. Babe the Blue Ox was Paul’s best friend. According to legends Babe was found during the winter of the Blue snow, the year that it was blue with cold. He was measured forty-two ax handles and plug of tobacco between the horns; he lived in harmony with his mate Bessie, the Yaller cow. Legend has it that Babe together with Paul Bunyan had footprints were so large that they created Minnesota’s ten thousand lakes. Babe when thirsty could even drink a river dry.

Babe the Blue Ox was Paul’s best friend. According to legends Babe was found during the winter of the Blue snow, the year that it was blue with cold. He was measured forty-two ax handles and plug of tobacco between the horns; he lived in harmony with his mate Bessie, the Yaller cow. Legend has it that Babe together with Paul Bunyan had footprints were so large that they created Minnesota’s ten thousand lakes. Babe when thirsty could even drink a river dry.

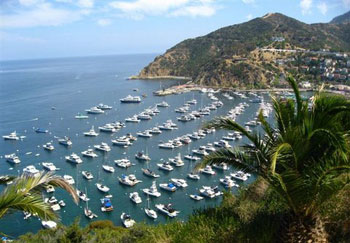

The island is now operated by the Santa Catalina Conservancy. The county of Los Angeles provides administration, including firefighters (who are barged over from the mainland when needed; the local force is voluntary), and police (which are hardly required, according to locals, because crime on the island is seldom a problem due to the lack of escape routes).

The island is now operated by the Santa Catalina Conservancy. The county of Los Angeles provides administration, including firefighters (who are barged over from the mainland when needed; the local force is voluntary), and police (which are hardly required, according to locals, because crime on the island is seldom a problem due to the lack of escape routes). My wife and I, her sister and a friend, booked a package deal in Avalon which included a night’s stay at the Casa Mariquita Hotel on Metropole Avenue and two ferry tickets from Long Beach. This saved us about $20 a couple over booking them separately. Note that when you’re doing your online research to make sure the hotel has a deal with a ferry company leaving from a location convenient for you; they don’t all. Long Beach is closest to Los Angeles.

My wife and I, her sister and a friend, booked a package deal in Avalon which included a night’s stay at the Casa Mariquita Hotel on Metropole Avenue and two ferry tickets from Long Beach. This saved us about $20 a couple over booking them separately. Note that when you’re doing your online research to make sure the hotel has a deal with a ferry company leaving from a location convenient for you; they don’t all. Long Beach is closest to Los Angeles. There is a good selection of hotels, as befits an island almost entirely geared to tourism. Our one-night stay at the Casa Mariquita was $175 and represented the lower to mid level what you might expect to pay. It was entirely satisfactory. There is no dining room, but walking to any of the many eateries down the street just adds to the experience.

There is a good selection of hotels, as befits an island almost entirely geared to tourism. Our one-night stay at the Casa Mariquita was $175 and represented the lower to mid level what you might expect to pay. It was entirely satisfactory. There is no dining room, but walking to any of the many eateries down the street just adds to the experience.

Past the Casino, past the Tuna Club (the oldest sport fishing club in North America, founded 1898), the path continues to wind along the rocky ocean shore to what might be called a “suburb” of Avalon, Descanso Beach, which seems to cater to a younger crowd than the main town with lots of swimming, snorkeling, and kayaking. There is a large restaurant (the Descanso Beach Club) and plenty of boutiques selling beach wear and souvenirs. The area is only open during the tourist season, from mid-April to mid-October.

Past the Casino, past the Tuna Club (the oldest sport fishing club in North America, founded 1898), the path continues to wind along the rocky ocean shore to what might be called a “suburb” of Avalon, Descanso Beach, which seems to cater to a younger crowd than the main town with lots of swimming, snorkeling, and kayaking. There is a large restaurant (the Descanso Beach Club) and plenty of boutiques selling beach wear and souvenirs. The area is only open during the tourist season, from mid-April to mid-October. The weather in the summer is typical Southern California: Hot and sunny, low humidity, cool breezes. The locals advised us it “gets cool at night”, but that meant a dip into the high teens Celsius (mid 60s Fahrenheit); what a northerner calls “refreshing”.

The weather in the summer is typical Southern California: Hot and sunny, low humidity, cool breezes. The locals advised us it “gets cool at night”, but that meant a dip into the high teens Celsius (mid 60s Fahrenheit); what a northerner calls “refreshing”.

He gestures “trouble” and stands in front of me, placing his hands on my shoulders. His dark eyes penetrate me with their intenseness. A sharp pang of grief cuts through me. He stands quietly allowing me a moment of reflection. I realize then that, although I am his captive, I am also his lover.

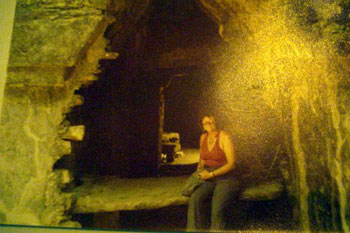

He gestures “trouble” and stands in front of me, placing his hands on my shoulders. His dark eyes penetrate me with their intenseness. A sharp pang of grief cuts through me. He stands quietly allowing me a moment of reflection. I realize then that, although I am his captive, I am also his lover. It wasn’t until nearly a year later in a place thousands of miles away in south-eastern Mexico that I would find some of the answers. I was traveling with two friends by van from the Mexican Caribbean coast of the Yucatan to the humid jungle area of the Chiapas, heading for the archaeological site of Palenque. We planned to spend the day exploring the ancient Mayan ruins. As I entered the site I was awed by what I saw. A mysterious jade-colored aura shimmers over the entire area where temples, palaces and pyramids with roof ornaments carved in stone preside magnificently over the gloomy, mysterious rain forest that surrounds it. It is easy to imagine every building in its perfection with the terraces and gardens that gave Palenque the reputation of having been one of the most beautiful of the ancient Mayan cities.

It wasn’t until nearly a year later in a place thousands of miles away in south-eastern Mexico that I would find some of the answers. I was traveling with two friends by van from the Mexican Caribbean coast of the Yucatan to the humid jungle area of the Chiapas, heading for the archaeological site of Palenque. We planned to spend the day exploring the ancient Mayan ruins. As I entered the site I was awed by what I saw. A mysterious jade-colored aura shimmers over the entire area where temples, palaces and pyramids with roof ornaments carved in stone preside magnificently over the gloomy, mysterious rain forest that surrounds it. It is easy to imagine every building in its perfection with the terraces and gardens that gave Palenque the reputation of having been one of the most beautiful of the ancient Mayan cities.

I walked from temple to temple. In each of those cool, damp sanctuaries, the spirits of former inhabitants whispered, waiting for recognition. The air was humid, carrying the fragrance of decaying and luxuriant growth and the scent of tropical flowers. Birds twittered gaily and fluttered about the roof-combs where they nested, the only inhabitants now.

I walked from temple to temple. In each of those cool, damp sanctuaries, the spirits of former inhabitants whispered, waiting for recognition. The air was humid, carrying the fragrance of decaying and luxuriant growth and the scent of tropical flowers. Birds twittered gaily and fluttered about the roof-combs where they nested, the only inhabitants now.