By Blaine Bonham

Eleven year-old Safet Begic played with a friendly stray dog almost every day outside his family’s apartment between bombings by Serbian forces on Logavina Street in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Hercegovina’s capital. One day, when the shelling stopped, he went outside to play with his friend. The dog growled and snarled and chased him, despite his repeated attempts to pet her. So he went back inside. Moments later. a bomb fell in front of their apartment and killed the dog. He claims the dog saved his life. That was 1993.

Safet became our personal guide on for a beautiful September day in this atmospheric city. Sarajevo was the last stop on a month-long journey through the Balkans in southeastern Europe. I studied the 1992—1995 Bosnian War to prepare for the visit. Like most Americans, the conflict in the early 1990s served as occasional news flashes and headlines for me. With no American skin in the game, it was a distant horror. I wanted to understand the nature of the animosities among ethnic and religious groups that led to the tragic siege of once beautiful Sarajevo, site of the 1984 Winter Olympics. The region is known for its stunning mountainous landscape and its rich, multicultural blend of Ottoman and European architecture. I often wondered how a tragedy like the four-year siege could happen to such a place…though the very differences that created this blend was also the touchstone for World War I war early in the twentieth century.

Safet became our personal guide on for a beautiful September day in this atmospheric city. Sarajevo was the last stop on a month-long journey through the Balkans in southeastern Europe. I studied the 1992—1995 Bosnian War to prepare for the visit. Like most Americans, the conflict in the early 1990s served as occasional news flashes and headlines for me. With no American skin in the game, it was a distant horror. I wanted to understand the nature of the animosities among ethnic and religious groups that led to the tragic siege of once beautiful Sarajevo, site of the 1984 Winter Olympics. The region is known for its stunning mountainous landscape and its rich, multicultural blend of Ottoman and European architecture. I often wondered how a tragedy like the four-year siege could happen to such a place…though the very differences that created this blend was also the touchstone for World War I war early in the twentieth century.

After Yugoslavia’s dissolution in 1992, the region devolved into open conflict. The dominant Orthodox Christian Serbs, who held the power in the former united country, attacked Catholic Croatia when it declared its independence. Serbian forces in Bosnia next turned its forces against Muslim Bosnia. Attempting to enlarge its territory, Croatia also attacked Bosnia, which contained a sizable Croatian population. Ethnic cleansing, perpetrated by Serbs on Muslim Bosnians, became the shame of this conflict.

Sarajevo’s residents considered the city an idyllic melting pot of Muslims, and Catholic and Orthodox Christian cultures, whose followers long ago learned to live side by side peacefully together. So they were unprepared for the Serbian army’s surprising attack on April 5, 1992. The ensuing siege killed 11,500 civilians and defending soldiers by with bombs, starvation, and sniper fire. And pulverized large parts of the historic, architecturally notable city in the process.

Safet is a tall, slender mid-30s man of with European features and mixed Muslim and Christian background. His light brown hair offset a darker mustache and even darker goatee. Despite his the gentle, soft-spoken demeanor, his enthusiasm, knowledge, and love for his city provided an instructive eye-opening experience.

Our first stop was the beautifully restored Stari Grad, or Old Town, featuring religious structures and unique Bosnian building style. The eastern half has winding lanes laid out by the Ottomans in the fifteenth century as a souk, or Turkish marketplace. The western end of Old Town features architecture and culture that developed under Austro-Hungarian rule beginning in the late nineteenth century.

Closed to traffic, the souk area vibrates with an energy and influence from East and West culture. Iconic Pigeon Square, featured in every series of Sarajevo photographs, is the gateway to the souk. At its center, an 1891 ornately carved wooden Ottoman drinking fountain is now a gathering place for flocks of the oddly iridescent gray birds and their human feeders. Two women and their children were immersed in a cloud of flapping birds devouring breadcrumbs from hands and the ground. One child waved his hands wildly, and a purplish-gray cloud of wings rose into the air, only to settle down seconds later to feed again.

Closed to traffic, the souk area vibrates with an energy and influence from East and West culture. Iconic Pigeon Square, featured in every series of Sarajevo photographs, is the gateway to the souk. At its center, an 1891 ornately carved wooden Ottoman drinking fountain is now a gathering place for flocks of the oddly iridescent gray birds and their human feeders. Two women and their children were immersed in a cloud of flapping birds devouring breadcrumbs from hands and the ground. One child waved his hands wildly, and a purplish-gray cloud of wings rose into the air, only to settle down seconds later to feed again.

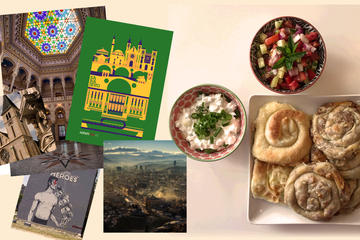

Crowds of travelers, tourists, and mostly Muslim locals—including clusters of laughing, school-age young women wearing hijabs—strolled the lanes window-shopping. Clothing, books, colorful rugs, sweet and savory foods, copper and silver souvenirs, and wooden and ceramic tchotchkes are for sale. To fuel activities, dozens of restaurants serve falafel, spicy meat pies, flatbreads and olives, and assorted local dishes. Cafes are ubiquitous, and cafe sitting is a treasured pastime in Sarajevo. A dark-haired, black-mustached waiter taught me how to properly drink the viscous black Bosnian coffee: hold a sugar cube in my mouth to sweeten it as I drink.

Crowds of travelers, tourists, and mostly Muslim locals—including clusters of laughing, school-age young women wearing hijabs—strolled the lanes window-shopping. Clothing, books, colorful rugs, sweet and savory foods, copper and silver souvenirs, and wooden and ceramic tchotchkes are for sale. To fuel activities, dozens of restaurants serve falafel, spicy meat pies, flatbreads and olives, and assorted local dishes. Cafes are ubiquitous, and cafe sitting is a treasured pastime in Sarajevo. A dark-haired, black-mustached waiter taught me how to properly drink the viscous black Bosnian coffee: hold a sugar cube in my mouth to sweeten it as I drink.

We stopped for lunch at a small restaurant to eat cevapi, the country’s national dish. Ten minced meat sausages are grilled and inserted inside a warmed flatbread, then drizzled with a cottage cheese or sour cream sauce and topped with cubed raw or fried onions. As I peered at the menu through the bottom half of cheap bifocal sunglasses, the owner tapped me on the shoulder. I handed him my glasses, and he returned to the counter where he and three workers each tried them on. He nodded approval as he returned them and took our order.

We visited the courtyard of the sixteenth century Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque, the Bosnian Islamic community’s main congregational mosque, and one of the most important Ottoman structures in the Balkans. Women and men prayed separately in the portico on either side of the main temple doors. Down the next street, a group of middle-aged men played chess on a 10-foot square board of colored pavers with giant two-foot high pieces in the courtyard of an Serbian Orthodox Church. Three young Muslim men stopped to ask us tentatively if they were allowed to enter a Catholic church. (“Certainly,” we told them. Alas, the church was closed for a private function.)

We visited the courtyard of the sixteenth century Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque, the Bosnian Islamic community’s main congregational mosque, and one of the most important Ottoman structures in the Balkans. Women and men prayed separately in the portico on either side of the main temple doors. Down the next street, a group of middle-aged men played chess on a 10-foot square board of colored pavers with giant two-foot high pieces in the courtyard of an Serbian Orthodox Church. Three young Muslim men stopped to ask us tentatively if they were allowed to enter a Catholic church. (“Certainly,” we told them. Alas, the church was closed for a private function.)

Safet pointed out one of the thousands of “Sarajevo roses,” the pockmarks on streets and sidewalks where Serbian snipers’ shells exploded, spraying bouquets of divots that damaged the paving. Today the pavement blemishes are painted with a red resin to honor citizens killed by wartime shrapnel and to symbolize the rebirth of the city. “It’s so we never forget,” Safet told us.

We visited the spot where 19-year-old Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip assassinated Austro-Hungarian Archduke Ferdinand and his wife Sofie in 1914, precipitating World War I. A separate museum featured a graphic exhibition of the war atrocities of 25 years ago. Many buildings in Stari Grad still bore the scars of mortar attacks. The historical evidence of conflict and tragedy contrasts with Sarajevo’s present-day vibrancy.

The Tunnel Museum, built onto the house whose cellar was the tunnel entrance, featured rooms depicting the horrible daily living conditions among the besieged. Maps and diagrams, footage of the tunnel’s excavation and use, and war films of active fighting underscored the heroic efforts of everyday people to support each other. The tunnel ran under the airport and connected to a Bosnian-held neighborhood. Freedom fighters laid tracks for pushcarts to bring in food, arms, and humanitarian aid, though the tunnel was often half-filled with water. Crawling through the remaining 65 feet of the tunnel caused a sickening, claustrophobic feeling.

The Tunnel Museum, built onto the house whose cellar was the tunnel entrance, featured rooms depicting the horrible daily living conditions among the besieged. Maps and diagrams, footage of the tunnel’s excavation and use, and war films of active fighting underscored the heroic efforts of everyday people to support each other. The tunnel ran under the airport and connected to a Bosnian-held neighborhood. Freedom fighters laid tracks for pushcarts to bring in food, arms, and humanitarian aid, though the tunnel was often half-filled with water. Crawling through the remaining 65 feet of the tunnel caused a sickening, claustrophobic feeling.

Throughout the day, Safet shared many of his personal experiences as a young teenager during the siege. His family was forced to move frequently, as various neighborhoods were bombed or buildings hit. Often they had no heat, so hunting for anything to use as fuel was a daily challenge. Sarajevans valued furniture and shoes for burning in makeshift stoves. They searched for fresh drinking water every day, all the time dodging shrapnel and sniper fire. Safet and his father often made the dangerous journey on foot to the local brewery, which escaped bombing, to get for fresh water to carry home in pails and jugs.

The family sometimes ate canned war rations from the Vietnamese War, compliments of the American government. Safet’s mother supplemented small amounts of flour she found with sawdust to make bread and biscuits. At one point, she was hospitalized to give birth to Safet’s brother. When the hospital was bombed, she and her newborn son evacuated to safer temporary facilities. Safet should hate, but I did not sense that he did. A lover of jazz and an expressionist artist, he seems to live his life partly at peace and partly as an activist for peace. He hopes the best for a world that allows people to live freely, but he also fears that the forced peace settlement brokered by President Clinton’s administration sowed the seeds for future strife.

After we parted from Safet, I took a walk to Logavina Street, where Safet lived briefly during the war. Before the trip, I read Barbara Demick’s book, Logavina Street: Life and Death in a Sarajevo Neighborhood. Ms. Demick was the foreign desk reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer who covered the Bosnian War from 1992-95, spending several months there over four visits. Her reporting focused on the people of Logavina Street—Muslims, Croats, and Serbs—as neighbors and friends. Ms. Demick chronicled the lives of individual families, some killed in bombings, others who turned against each other, informing enemy forces about where Muslim families lived.

I climbed the steep street, reliving what happened to the families who lived there, noting the house numbers and the damaged and repaired buildings or brand new structures that replaced rubble. At the top of the long hill, I came to the school where families took refuge in the basement from the bombing, some living there for months. Now it was a refurbished, functioning school again.

A mother in her early 30s, black hair pulled back into a ponytail, walked out the front door with her two little boys, dressed in matching army green bomber jackets. She lived right across the street from the school as a young girl during the siege. Artillery fire bombarded her house several times. I asked her about the dozens of plaques with names on them that covered the building’s front wall. They named former students who were killed during the war. Most schools displayed similar plaques, she said. She gave me permission to take their photo. Her smile and her sons’ eager faces are a hopeful footnote to my emotional visit to Logavina Street’s tragic history.

I fell quickly in love with this phoenix of a city. Its residents, with the help of the European Union, rebuilt and restored much of Sarajevo’s physical structure. They imbued it with an upbeat vibe and exciting, multicultural life again.

If You Go:

Full-Day Herzegovina, Mostar, and Blagaj Tekke Tour from Sarajevo

By plane — Sarajevo International Airport is 12kms from city centre. Connects thru international hubs in Istanbul, Vienna, Berlin, Munich, others

By train — connects to Zagreb, Croatia. Suitable for low-budget travelers

By bus — Centrotrans Eurolines, Biss Tours, and Globtours connect to major European cities

Lodging — Home Away apartment rentals

Guide — Safet Begic Email: safetbeg@yahoo.com

Sarajevo Cultural Walking Tour with Local Food Tasting

About the author:

A former non-profit management professional in the urban horticulture field, Blaine enjoys traveling the globe with his husband Rick to places less culturally typical of his hometown of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He captures images and records his experiences to understand the world he lives in, sharing his photos and stories on his website www.blainebonhamphoto.com.

Top photo by Alen Djuderija Photography from Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina / CC BY

All other photos by Blaine Bonham.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.