by Victor A. Walsh

The eight-mile dirt road zigzags through the parched hills like the river of no return. The grasses and thistles, now a golden brown, sparkle in the November sunlight. Not a blade of grass moves in the stillness. Hills and gullies stretch out in all directions like a wrinkled, windblown sheet.

At the parking lot we meet an older maintenance worker with National Parks. His deeply furrowed face is as rough as the terrain. He tells us that the Fort Bowie National Historic Site is about a mile-and-a-half down the trail. I ask him about the jutting mountain peaks on the horizon in front of us. “Those are the Chiricahua Mountains,” he says. “Geronimo use to talk to his gods up there.”

The trail winds through meadows dotted with mesquite and rimmed by hills. The foot-high grasses, bent and curled by gusting winds, have turned a rich golden yellow. It is warm, quiet — an inviting place of solitude.

The trail winds through meadows dotted with mesquite and rimmed by hills. The foot-high grasses, bent and curled by gusting winds, have turned a rich golden yellow. It is warm, quiet — an inviting place of solitude.

But 155 years ago, the last Indian war in the United States erupted here between the native Chiricahua Apache and the U.S. military. The incident that ignited the bloodshed was the kidnapping of a local rancher’s son. Settlers falsely accused Cochise, the chief of the local Chiricahua, of taking the boy. When he was not returned, a brash young officer, Lieutenant George N. Bascom, detained and executed several of Cochise’s relatives. Cochise, in turn, executed his American and Mexican hostages, and a tenuous peace was broken forever.

Markers along the way identify the remnants of a Butterfield Stage station attacked by Cochise’s warriors, the restored post cemetery, a reconstructed Apache wickiup, and the Chiricahua Apache Indian Agency adobe ruin.

A weathered picket fence encloses the cemetery. Long, narrow shadows from the rows of white headstones slice through the sunlit gold-brown grass. In 1895, the army removed the remains of all military personnel for re-internment at the San Francisco National Cemetery. Twenty-three gravesites remain — nearly all civilians employed at the fort.

I stare at the names on the headstones: John Finkle Stone, age 24; John Slater, age 35; John McWilliams, age 26. Below each name are the words, “Killed by Apaches.” They died young, too young, as did Geronimo’s two-year old captured son, Little Robe, buried here after dying in 1885 from dysentery.

Facing the sun, I look at the brown hills dotted with mesquite and scrub oak. Behind them, invisible in the glaring light, are the Chiricahua Mountains, the spiritual homeland of a people banished by conquest. Today they are part of Chiricahua National Monument.

Facing the sun, I look at the brown hills dotted with mesquite and scrub oak. Behind them, invisible in the glaring light, are the Chiricahua Mountains, the spiritual homeland of a people banished by conquest. Today they are part of Chiricahua National Monument.

Beyond the cemetery, the trail follows a dried river gulch shaded by thickets and saplings. Here, tucked below the pass is what drew the Apaches, Spaniards, and Americans: a year-round spring. Today its water is but a trickle, played out by history.

Climbing up an incline, I see a line of crumbling mottled-brown adobe walls in the glinting sunlight sprawled across Apache Pass. An unfurled American flag hangs limply from its post on the parade ground.

I walk among the ruins — the massive cavalry barracks, the stables, and ordinance building — trying to imagine a world gone: barking dogs, a wagon lumbering up the old stage route; soldiers with their mounts and carbines. The officer’s quarters, a two-story, Victorian-style frame building with a shingled mansard roof, once stood on the far side of the parade ground. Now nothing remains but a marker stranded amidst clumps of dry grass.

I walk among the ruins — the massive cavalry barracks, the stables, and ordinance building — trying to imagine a world gone: barking dogs, a wagon lumbering up the old stage route; soldiers with their mounts and carbines. The officer’s quarters, a two-story, Victorian-style frame building with a shingled mansard roof, once stood on the far side of the parade ground. Now nothing remains but a marker stranded amidst clumps of dry grass.

I wonder what the men and their families thought or how they coped with the physical isolation of this remote place, and the lurking presence of a determined enemy defending their homeland.

Rebuilt and enlarged in the late 1860s to protect the spring and overland route, Fort Bowie never had walls, but it played a vital role as the base of operations in the last Apache war against the shaman and war chief Geronimo.

After his surrender, Geronimo and thirty-six of his followers were brought to the parade ground and loaded into wagons on September 8, 1886, destined for military prison in Florida. The entire tribe, including those who never resisted, suffered a similar fate until 1913 when 265 survivors — many born in captivity — were at last released from Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

With Geronimo’s final surrender, the fort’s raison d’être ended. In 1894, it was closed, and the small garrison reassigned to a new post in Colorado. The abandoned post quickly fell into disrepair as locals carried off timbers, windows and doors. In 1911, the Chiricahua lands west of the fort, once protected as a military reservation were auctioned off.

In the fleeting light, the adobe walls and stone ruins stand like sentinels to a time when the Chiricahua Apache waged the last major Indian resistance against the United States. They had lost their families, homes, horses, guns, and freedom—everything but their honor.

If You Go:

Getting There:

The Fort Bowie, which became a National Historic Site in 1964, is located 13 miles south of Bowie on Apache Pass Road off I-10 and 20 miles southeast of Willcox off 186. From Tucson it is 166 miles via I-10.

Attractions:

The rural community of Willcox, founded in 1880 as a camp for Southern Pacific Railroad construction crews, has a colorful history that its citizens are striving to preserve. Many of the late 19th-century commercial buildings are still intact, including the restored railroad depot, a National Historic Landmark.

The forest of spires, balanced rocks and pinnacles in nearby Chiricahua National Monument is well worth a visit. To the Chiricahua the mountains were known as the Land of Standing-Up Rocks. The monument’s 12,000 acres encompass two deserts and two mountain ranges, and is home to a wide range of plants and animals.

Accommodations:

Hotels, inns and B&Bs are available at Bowie, 14 miles north of the ruin on I-10 and Willcox, 27 miles west along AZ-186. Bonita Canyon Campground at Chiricahua National Monument is open year-round. Sites are available by online reservations. RV hookups and camp sites are available nearby at Alaskan and Mountain View RV Parks on I-10.

For More Information:

Fort Bowie National Historic Site, 3203 South Old Fort Bowie Rd, (520) 847-2506. There is a visitor center and rear access road for disabled visitors.

Fort Bowie, Arizona, Combat Post of the Southwest 1858-1894 by Douglas C. McChristian, University of Oklahoma Press.

About the author:

Victor A. Walsh’s passion is the trans-Missouri West with a focus on early explorations and their continuing impact on our world today. His historical and travel essays have appeared in American History, True West, Literary Traveler, California History, Journal of the West, Rosebud, Desert Leaf, among other publications.

Photos by Richard Miller and Victor A. Walsh

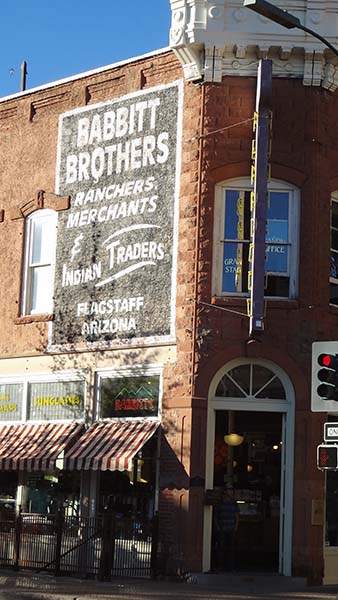

In fifteen minutes I reach the historic center, a memorable assortment of 19th century architecture that is perfect for exploring on foot. There are few specific tourist attractions here, but wandering the hodgepodge of 1890s-era redbrick buildings, many of which flaunt stone and stucco friezes, conjures up visions of the Old West. When the downtown area became rundown in the 1960s, city officials considered demolishing many of the worn structures to build carparks for the increasing numbers of tourists. Thankfully, they realized that if they tore down all the old buildings there would be little reason for tourists to visit.

In fifteen minutes I reach the historic center, a memorable assortment of 19th century architecture that is perfect for exploring on foot. There are few specific tourist attractions here, but wandering the hodgepodge of 1890s-era redbrick buildings, many of which flaunt stone and stucco friezes, conjures up visions of the Old West. When the downtown area became rundown in the 1960s, city officials considered demolishing many of the worn structures to build carparks for the increasing numbers of tourists. Thankfully, they realized that if they tore down all the old buildings there would be little reason for tourists to visit.

“It looks like a place where the dinosaurs once roamed frozen in a time capsule of volcanic rock,” I gasp.

“It looks like a place where the dinosaurs once roamed frozen in a time capsule of volcanic rock,” I gasp.

Harry continues driving along the route made famous in John Ford’s classic film Stagecoach (1939) through an eerie, snow-dusted landscape of gouged, red-brown hills and gullies cradled by massive buttes. It’s as if nothing has changed since that time. There are no paved roads, power lines, restaurants or public restrooms — just a few scattered Navajo hogans veiled in gray mist. But everything, including the Navajo’s traditional way of life, is changing.

Harry continues driving along the route made famous in John Ford’s classic film Stagecoach (1939) through an eerie, snow-dusted landscape of gouged, red-brown hills and gullies cradled by massive buttes. It’s as if nothing has changed since that time. There are no paved roads, power lines, restaurants or public restrooms — just a few scattered Navajo hogans veiled in gray mist. But everything, including the Navajo’s traditional way of life, is changing. Navajo elders remember snows from the 1940s that were chest high on horses. They mention grass so thick and tall that sheep could get lost in it and soil that stayed damp through spring. It was a world they understood and identified with, but weather patterns now are extreme and unpredictable with no seasonal order. “The wind today is different,” says Janis Perry. “It is upset with us. You can see it in our sheep. They are constantly fatigued.”

Navajo elders remember snows from the 1940s that were chest high on horses. They mention grass so thick and tall that sheep could get lost in it and soil that stayed damp through spring. It was a world they understood and identified with, but weather patterns now are extreme and unpredictable with no seasonal order. “The wind today is different,” says Janis Perry. “It is upset with us. You can see it in our sheep. They are constantly fatigued.”

All of this eludes me in winter’s cocoon at an elevation of 5,200’. In the afternoon light, the red-rock spires and mesas, sculpted in such a cacophony of shapes, rise above the dust-laden emptiness. They stand alone, as if haunted. North of Totem Pole, the wind hurls sand through twisted juniper trees and across the dusty road, gullies, dunes and knolls of fractured rock. As the sun fades, the horizon of misshapen rock formations looks eerily beautiful in the whirling wind.

All of this eludes me in winter’s cocoon at an elevation of 5,200’. In the afternoon light, the red-rock spires and mesas, sculpted in such a cacophony of shapes, rise above the dust-laden emptiness. They stand alone, as if haunted. North of Totem Pole, the wind hurls sand through twisted juniper trees and across the dusty road, gullies, dunes and knolls of fractured rock. As the sun fades, the horizon of misshapen rock formations looks eerily beautiful in the whirling wind. To the Navajo, Monument Valley, the first tribal park in the United States, is more than a park or nature preserve. It is one of the spiritual centers of their ancestral homeland, a living link to their culture and identity, quite separate from Ford’s mythic Westerns. Some visitors are drawn by the landscapes they remember from his movies, but Navajo guides instead share stories about the Holy Ones, healing ceremonies, rock art and their clans.

To the Navajo, Monument Valley, the first tribal park in the United States, is more than a park or nature preserve. It is one of the spiritual centers of their ancestral homeland, a living link to their culture and identity, quite separate from Ford’s mythic Westerns. Some visitors are drawn by the landscapes they remember from his movies, but Navajo guides instead share stories about the Holy Ones, healing ceremonies, rock art and their clans. “Monument Valley has an unusual power that anchors us,” Garry explains. “There is an inner harmony, beauty and peace. Navajo and non-Navajo, who come here, have been healed emotionally and physically. In our history, no invaders could come in and conquer it.” This included the brutal ‘Long Walk’ of 1863-1864 when the U.S. army under Colonel Kit Carson invaded and forcefully relocated thousands of Navajo people to a New Mexico wasteland called Bosque Redondo. Many of those who escaped capture found refuge in the valley.

“Monument Valley has an unusual power that anchors us,” Garry explains. “There is an inner harmony, beauty and peace. Navajo and non-Navajo, who come here, have been healed emotionally and physically. In our history, no invaders could come in and conquer it.” This included the brutal ‘Long Walk’ of 1863-1864 when the U.S. army under Colonel Kit Carson invaded and forcefully relocated thousands of Navajo people to a New Mexico wasteland called Bosque Redondo. Many of those who escaped capture found refuge in the valley. With its hidden burial sites and surreal rock formations infused with gods and spirits and the Navajo presence, Monument Valley is unlike any other place that I have visited. This becomes clear to me later when Harry, Dick and I drive to Ear of the Wind, a tunnel-like vaulted rock arch that opens up to the sky, where echoes from the wind can be heard. In my mind, it resembles a cave where a giant once stayed to watch his kingdom.

With its hidden burial sites and surreal rock formations infused with gods and spirits and the Navajo presence, Monument Valley is unlike any other place that I have visited. This becomes clear to me later when Harry, Dick and I drive to Ear of the Wind, a tunnel-like vaulted rock arch that opens up to the sky, where echoes from the wind can be heard. In my mind, it resembles a cave where a giant once stayed to watch his kingdom. Then a long sonorous cry pierces the silence. Maybe fifty or sixty feet away, we see a young Navajo chanter sitting on a rock ledge. He breathes deeply and then leaning forward, rocks his body back and forth as his high-pitched voice echoes off the canyon walls.

Then a long sonorous cry pierces the silence. Maybe fifty or sixty feet away, we see a young Navajo chanter sitting on a rock ledge. He breathes deeply and then leaning forward, rocks his body back and forth as his high-pitched voice echoes off the canyon walls.

I wound my way through the ruins on a trail which took me backward in time. Pueblo Grande began as a small settlement around AD 450 and grew to over fifteen hundred people. The mound village was one of the largest Hohokam settlements in the area. At one time there were over fifty mound villages in the Salt River Valley. They got their names from the platform mounds at their centre. The mounds were urban centres with large open plazas where ceremonies were likely performed and were built with trash or soil and then capped with caliche, a lime-rich soil found in the desert which makes a good plaster when mixed with water. Pueblo Grande also included residential “suburbs”, astronomical observation facilities, waste disposal facilities, and ball courts.

I wound my way through the ruins on a trail which took me backward in time. Pueblo Grande began as a small settlement around AD 450 and grew to over fifteen hundred people. The mound village was one of the largest Hohokam settlements in the area. At one time there were over fifty mound villages in the Salt River Valley. They got their names from the platform mounds at their centre. The mounds were urban centres with large open plazas where ceremonies were likely performed and were built with trash or soil and then capped with caliche, a lime-rich soil found in the desert which makes a good plaster when mixed with water. Pueblo Grande also included residential “suburbs”, astronomical observation facilities, waste disposal facilities, and ball courts. I walked past the remains of the platform mound, the ball court, special purpose rooms, and the Solstice Room. At summer solstice sunrise and winter solstice sunset, the sun’s rays passed through the corner door and onto another door in the middle of the south wall of the Solstice Room. Some researchers think the room may have been used as a calendar.

I walked past the remains of the platform mound, the ball court, special purpose rooms, and the Solstice Room. At summer solstice sunrise and winter solstice sunset, the sun’s rays passed through the corner door and onto another door in the middle of the south wall of the Solstice Room. Some researchers think the room may have been used as a calendar.

Pueblo Grande was built at the headwaters of a major canal system. The Hohokam cultivated many plant species, including maize, cotton, squash, amaranth, little barley, and beans. Unlike today, The Salt River ran year round during Hohokam days. But the arid desert environment did not produce enough rainfall to grow crops. The Hohokam built over one thousand miles of canals and engineered the largest and most sophisticated irrigation system in the Americas, no small feat considering the primitive tools they had.

Pueblo Grande was built at the headwaters of a major canal system. The Hohokam cultivated many plant species, including maize, cotton, squash, amaranth, little barley, and beans. Unlike today, The Salt River ran year round during Hohokam days. But the arid desert environment did not produce enough rainfall to grow crops. The Hohokam built over one thousand miles of canals and engineered the largest and most sophisticated irrigation system in the Americas, no small feat considering the primitive tools they had. Mesa Grande Cultural Park contains the ruins of a temple mound built by the Hohokam between AD 1100 and AD 1400. At first glance, I was not impressed with the site. Just a mound of dirt and a ditch. The site became more interesting as I walked through it and viewed it in context of the historical information provided on sign posts. The Park of the Canals contains no mound village but displays the remains of over four thousand feet of Hohokam canals in three different sections. Also located with the Park is the Brinton Desert Botanical Garden, a small garden containing plants found within the desert environment.

Mesa Grande Cultural Park contains the ruins of a temple mound built by the Hohokam between AD 1100 and AD 1400. At first glance, I was not impressed with the site. Just a mound of dirt and a ditch. The site became more interesting as I walked through it and viewed it in context of the historical information provided on sign posts. The Park of the Canals contains no mound village but displays the remains of over four thousand feet of Hohokam canals in three different sections. Also located with the Park is the Brinton Desert Botanical Garden, a small garden containing plants found within the desert environment.

Canals remain important to irrigation within the greater Phoenix area today with nine major canals and over nine hundred miles of “laterals”, ditches taking water from the canals to delivery points. Paths alongside the waterways are used for walking, running and biking. Scottsdale, one of the other cities in the greater Phoenix area, has turned a canal area into a modern meeting place and tourist draw. The banks of Scottsdale Waterfront, in a revitalized area of downtown Scottsdale, are lined with palm trees, public art, courtyards, fountains, and walking paths. The area contains restaurants, outdoor cafés, specialty shops, and high-rise residential buildings, and hosts music and art festivals. It feels worlds away from its ancient Hohokam roots.

Canals remain important to irrigation within the greater Phoenix area today with nine major canals and over nine hundred miles of “laterals”, ditches taking water from the canals to delivery points. Paths alongside the waterways are used for walking, running and biking. Scottsdale, one of the other cities in the greater Phoenix area, has turned a canal area into a modern meeting place and tourist draw. The banks of Scottsdale Waterfront, in a revitalized area of downtown Scottsdale, are lined with palm trees, public art, courtyards, fountains, and walking paths. The area contains restaurants, outdoor cafés, specialty shops, and high-rise residential buildings, and hosts music and art festivals. It feels worlds away from its ancient Hohokam roots.