By Bill Arnott

It was the coast that drew me. If you’ve watched BBC’s Coast you understand. Golden dunes, windswept marram and gemstone sea in tourmaline and sapphire. I’d come for a weeklong sailing excursion, one of eight people crewing a fifty-four-foot pilot cutter, a forty-year-old replica of a hundred-and-fifty-year-old boat. We started in Falmouth, sailing between Pendennis and St Mawes Castles, built by Henry VIII to keep Spanish at bay, literally. From here the Fal River meanders northeast toward London, its gaping maw the Carrick Roads – as critical a thoroughfare in Henry’s day as the M1 is today. Thus the castles, situated at Falmouth and St Mawes headlands, a heavily cannoned pincer where English Channel melds with Celtic Sea and North Atlantic.

Falmouth was a fitting start to my waterborne adventure, home to Cornwall’s National Maritime Museum – a blend of modern and ancient history with an indoor, hands-on sailboat pool. After a quick pint at the Chain Locker Pub, we set sail into sunset. Under engine power I took the helm, easing us through the harbor – a myriad of working tankers and pleasure craft, while our skipper boiled ham, potatoes and cabbage in the galley below.

We skirted the Lizard Peninsula (England’s most southerly point; the smell of sheep heavy in offshore breeze) past Land’s End into darkness, trundling our way into a force five gale. In our wake, bioluminescent phytoplankton glittered in our wake, mirroring a Milky Way sky. Our destination – the Isles of Scilly, a scattering of uninhabited rocks and five lightly populated islands – St Mary’s, St Martin’s, St Agnes, Tresco and Bryer. This archipelago used to be mainland. Honored dead were brought here – England’s most westerly point, closest to setting sun. Bronze Age burial chambers are scattered around the islands – the greatest concentration of accessible sites being on St Mary’s, along with the remains of an Iron Age village.

Sailing through the night we took turns at the wheel – no instruments to speak of, simply intuition, stars, and avoiding distant pinpricks of red – ocean-bound tankers, while a malfunctioning compass did nothing but spin. As waves grew, we offered up most of the skipper’s culinary efforts back to the sea, secondhand servings spewed into phytoplankton. Brewing and serving three AM tea became a contact sport. But as night wound down so too did the gale, and eerily calm morning greeted us as we sailed toward the Isles, a peach-hued sun rising from the sea into crepuscular sky.

The week was spent with a pleasant mix of sailing between islands, time on our own, hiking, beachcombing, sightseeing, and a mix of meals together aboard the boat and on land at welcoming pubs featuring regional real ales – local craft beers. At St Agnes I climbed huge copper coloured rocks abutting the shoreline before chowder and a Tribute at the Turks Head Pub. On St Martin’s we scattered, each of us finding our own secluded white sand beach. Rowers were hard at practice. The annual Isles of Scilly gig races are a huge international event. Roads are closed to allow the long, trailered boats to navigate winding throughways to the race site.

Across a narrow band of water is Tresco, home of Tresco Abbey Garden – a stunning green space boasting flora from across the globe (twenty-thousand plants from eighty countries). Tropical trees and plants thrive, as the Isles sit in the North Atlantic Gulf Stream with an almost Caribbean climate much of the year. Brilliant red and orange proteas, pink camellias, and lush palms cluster around the remains of a tenth century Benedictine Abbey – the Priory of St Nicolas, patron saint of sailors. Within the gardens sits the Valhalla Museum, an extension of the National Maritime Museum – a combination interior and open-air display of thirty sunken ships’ figureheads recovered from local waters over the centuries.

Across a narrow band of water is Tresco, home of Tresco Abbey Garden – a stunning green space boasting flora from across the globe (twenty-thousand plants from eighty countries). Tropical trees and plants thrive, as the Isles sit in the North Atlantic Gulf Stream with an almost Caribbean climate much of the year. Brilliant red and orange proteas, pink camellias, and lush palms cluster around the remains of a tenth century Benedictine Abbey – the Priory of St Nicolas, patron saint of sailors. Within the gardens sits the Valhalla Museum, an extension of the National Maritime Museum – a combination interior and open-air display of thirty sunken ships’ figureheads recovered from local waters over the centuries.

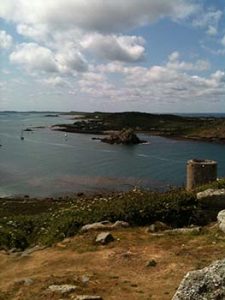

From the gardens I trekked north, from New Grimsby to Old Grimsby, climbing to the site of King Charles’ Castle, crenelated remains atop a pap of land with panoramic water views in South Pacific shades of teal. Through an arrow slit I spotted our cutter, Annabel J, anchored in the lee of a cove. (We’d tendered to shore in a small zodiac-style rhib.) The steep patch of rocky land was adorned in a ragged quilt of wild grass while the chortle of pheasants emanated from somewhere unseen. Far below, the cylindrical remains of Cromwell’s Castle fronts the water – these two crumbling structures collaborative historical pinpoints. Like Henry’s castle fortifications at Falmouth and St Mawes, the high-low battlements allowed a dual assault, lobbing cannonade from elevated ground while seaside guns skimmed cannonballs across the surface to pierce enemy ships at the waterline.

From the gardens I trekked north, from New Grimsby to Old Grimsby, climbing to the site of King Charles’ Castle, crenelated remains atop a pap of land with panoramic water views in South Pacific shades of teal. Through an arrow slit I spotted our cutter, Annabel J, anchored in the lee of a cove. (We’d tendered to shore in a small zodiac-style rhib.) The steep patch of rocky land was adorned in a ragged quilt of wild grass while the chortle of pheasants emanated from somewhere unseen. Far below, the cylindrical remains of Cromwell’s Castle fronts the water – these two crumbling structures collaborative historical pinpoints. Like Henry’s castle fortifications at Falmouth and St Mawes, the high-low battlements allowed a dual assault, lobbing cannonade from elevated ground while seaside guns skimmed cannonballs across the surface to pierce enemy ships at the waterline.

Back aboard the cutter we sailed amongst the Western Rocks, the last vestige of English soil in these parts, and gazed out to Bishop’s Rock Lighthouse – a fifty-meter-high tower of granite constructed in the 1850s – a show of strength, engineering skill, and safe passage to North Atlantic trade routes. Grey seals lolled on wave-swept rocks and barked as we passed, their herring breath wafting across the water. I dropped a handheld trolling line for mackerel, pulling up nothing more than a clump of small mussels wrapped in sea asparagus. The tiny mussels I tossed back, the greens I munched contentedly, imagining myself keeping scurvy at bay. A huge sunfish rolled at the surface, somehow prehistoric. And these are basking shark waters – monstrous plankton eaters akin to Greenland sharks – the size of full-grown orcas. But it was later on the mainland when I finally saw one, snaking its way through slate breakers off Cape Cornwall, gorging itself on the same plankters that lit our way from Land’s End.

It would be our last full day on the Isles but as we regrouped to rhib back to the cutter, our skipper’s expression was strained. “We have to leave. Right now,” he said. “A force eight’s bearing down. Need to make it to Helford ahead of the storm.” The long narrow mouth of the Helford River, northeast of the Lizard, would be our safest shelter en route back to Falmouth. And so we sailed. Ten hard hours of racing ahead of the storm while wind and waves grew. Sun shone fiercely through cumulous. It was beautiful. And frightening, as angry twelve-footers smashed over the front half of our ship. We donned survival suits and tethered ourselves to lifelines, slip-sliding over wave-washed deck to adjust sheets and secure lines. The cutter laboured up swells and surfed into troughs with heightening tailwind. “Je-sus!” a shipmate hissed, as waves heaved past, high above our heads, an arm’s length away. And as we tacked into the relative shelter of Helford, sky turned monochrome with waves like basalt. What was lovely before turned truly ugly. We struggled to lash the boat to a partially submerged buoy, the only available moorage. All hands worked to tie every available rope while I got the miserable task of sliding into the slender, cramped chain locker to jimmy the windlass and release the anchor chain, which had managed to knot itself as we were tossed about in the swells.

Finally secured, we bounced our way to shore in the rhib, where we stumbled into an unassuming sailing club for long showers, scraping away salt and sunscreen, before sitting communally for fish and chips, ale, whisky, and the laughter of exhaustion and relief.

If you go

Fly to Heathrow or Gatwick, express train or bus to Paddington or Reading, and train Great Western Lines toward Penzance. Transfers from Truro are required to Falmouth. You can find Annabel J info at annabel-j.co.uk. Alternately, you can train to Penzance and ferry to the Isles of Scilly aboard the Scillonian, which is notoriously rough – a shallow draft required to navigate these waters, making the vessel as balanced as a punching clown. Small plane flights go from Land’s End to Scilly, while helicopter access may be available depending on current carriers (which come and go). If not on a boat, Scilly accommodations should be booked in advance. Many places only offer bookings in one-week, Friday to Friday increments. St Mary’s is the most populace island (two-thousand inhabitants) with the most amenities and the small airport. Allow for entry fees to museums and Tresco Abbey Gardens.

About the author:

Author, poet, songwriter Bill Arnott is the bestselling author of Gone Viking: A Travel Saga and Dromomania: A Wonderful Magical Journey. Bill’s articles and columns are published in Canada, the US, UK, Europe and Asia. When not trekking the globe with a small pack, weatherproof journal and horribly outdated camera phone, Bill can be found on Canada’s west coast, making friends and generally misbehaving. amazon.com/author/billarnott_aps

Photos by Bill Arnott