by Troy Herrick

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Renaissance Europe extended itself out into the New World in search of wealth and to spread Christianity. The Spanish employed a more direct approach through conquest, looting and the forcible conversion of the Aboriginal population of Central and South America to the Catholic Faith. The French, on the other hand, had a more peaceful and cooperative approach with their stone age contemporaries through trading posts and Christian missions. European manufactured goods were exchanged for the Indians’ animal pelts while Jesuit priests would spread Christianity and conversion was voluntary. Both cultures benefited, evolved and prospered.

The origins of Canada’s resource-based economy date back to the 17th century with the establishment of New France – a private colony run by a French fur trading company. Where is the best location for a trading post? The answer was obvious. Go where the Aboriginals gather or camp. It all began on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River at the site known as Tadoussac where the first in a string of trading posts and missions was established.

Tadoussac

Tadoussac has the distinction of being the oldest village in Canada as well as the oldest surviving French settlement in the Americas. Pierre de Chauvin, who was granted a fur trading monopoly by King Henry IV, chose this site for colonization and a small trading post in 1600 because it was already known to Basque and Norman whalers. Tadoussac was also a traditional Aboriginal site for barter. What better location for having the furs brought directly to you? There was also a safe bay for sheltering ships. All Chauvin had to do was supply the settlement with items for trade and colonists.

Unfortunately, what Chauvin overlooked was the rugged terrain, poor soil and cold winters in this region, all of which proved to be quite taxing. Only 5 of the original 16 ill-prepared colonists survived the first winter and that was only because of Aboriginal intervention with food, shelter and natural medications. This trading relationship flourished and by 1603 the French were welcomed by the people they had named Montagnais or “Mountain People” as permanent settlers and as allies.

During the height of the French Fur Trading Period, Tadoussac Bay was filled with trans-Atlantic sailing vessels. Even today it is not unusual to find tall ships arriving. On the day of our visit there was a lone two-masted ship anchored offshore and it was flying the Jolly Roger.

Feeling that we would not encounter any pirates today, we walked to the site of the oldest trading post in Canada. The present Chauvin Trading Post structure, dating to 1942, is a well-worn replica of the original. You find a steeply pitched red roof over rough cut wooden walls. The peeling white paint on the exterior walls betrays the age of the structure. This property is enclosed within a 4-foot high wooden fence made from 2 to 3-inch thick tree branches. Two wigwam frames and a life-sized wooden Indian carved from a tree trunk complete the décor.

Inside you find a stone fireplace in the centre of the room and a canoe suspended from the ceiling. French fur traders learned how to travel along the rivers and lakes of the new land from the Indians by means of such a canoe and it was their lifeline.

Displays include examples of typical European items for trade such as axes, knives, metal pots, blankets, coats and even milled flour. The French did not provide alcohol for trade. Other displays include samples of various pelts such as beaver, martin, wolf and bear. Beaver was the most highly-prized pelt because it was used for fashionable men’s hats in Europe at the time. The French developed a reputation for fair trade as they could not afford to risk losing their sole source of furs – their allies the Montagnais.

Jesuit missionaries later arrived to establish the first mission in 1640 and build upon the friendly relations between the French and the Montagnais. Their goal was to convert the Indians to Christianity.

A short walk down the street from the trading post, you find the Petite Chapelle de Tadoussac, the oldest wooden church in Canada. Dating to 1747, this church was associated with the early Jesuit Mission. Oriented toward the St. Lawrence River, the exterior of the church features white-washed walls and a bright red roof and steeple. Climb the 8 stone steps and enter the church. Inside you find a very basic, rough wooden interior with two rows of eight pews in the nave. The rectangular interior ends in a semi-circular chancel housing a white altar decorated with gold colored trim. Behind the altar is a sacristy. This church is known to house some of the original items used in the first mass celebrated here but I was not able to confirm this with anyone.

A short walk down the street from the trading post, you find the Petite Chapelle de Tadoussac, the oldest wooden church in Canada. Dating to 1747, this church was associated with the early Jesuit Mission. Oriented toward the St. Lawrence River, the exterior of the church features white-washed walls and a bright red roof and steeple. Climb the 8 stone steps and enter the church. Inside you find a very basic, rough wooden interior with two rows of eight pews in the nave. The rectangular interior ends in a semi-circular chancel housing a white altar decorated with gold colored trim. Behind the altar is a sacristy. This church is known to house some of the original items used in the first mass celebrated here but I was not able to confirm this with anyone.

Over time, local fur resources were depleted which necessitated traders to extend their reach out further by means of more distant trading posts such as those at Chicoutimi and Metabetchouane to the northwest. This was facilitated by the coureurs des bois (runners of the woods). Qualifications for such a position included a willingness to go native, paddling a canoe for up to 18 hours a day and capable of carrying at least two 90-pound bundles of furs at a time over a portage. Some portages were as long as 6 miles. Such a harsh lifestyle was not financially conducive to a comfortable and early retirement. Hernias and other serious injuries were common.

The coureurs des bois traveled up the Saguenay Fjord to Chicoutimi by water. Diane and I had a car and we did not have to lug heavy packs around portages. This allowed us to appreciate the beauty of the deeply chiseled Laurentian Mountains and the fjord, both having been carved out over successive ice ages. Steep rock faces ran along the river and heights of more than 450-feet were not uncommon along the way to Chicoutimi.

The coureurs des bois traveled up the Saguenay Fjord to Chicoutimi by water. Diane and I had a car and we did not have to lug heavy packs around portages. This allowed us to appreciate the beauty of the deeply chiseled Laurentian Mountains and the fjord, both having been carved out over successive ice ages. Steep rock faces ran along the river and heights of more than 450-feet were not uncommon along the way to Chicoutimi.

Chicoutimi

The Chicoutimi Trading Post and Jesuit Mission were established as early as 1676 on the site of an earlier Aboriginal settlement. At its peak, there were as many as 10 buildings including a chapel, store, clerk’s house and lodging for a Jesuit missionary. All good things must come to an end and this trading post was closed in 1856. The site continued to host a functioning chapel until 1930 when it too was demolished. Now all that remains is a marker to commemorate the trading post. With this we drove on to Metabetchouane Trading Post at Des Biens.

Des Biens

The Montagnais would tell horror stories to the French about scary monsters and dangers lurking in the Lac St. Jean in order to keep them out of the region filled with rich fur resources. This changed in 1647 when Jesuit missionary Jean de Quen was guided into the Des Bien area to assist with treating a large number of ill people. At the time, De Quen made no mention of the Metabetchouane River entering the lake at this location but he did not leave without establishing a church in the vicinity.

The accessibility of this location was not apparent until a second Jesuit, Charles Albanel, returned to attend a meeting of twenty Indian nations in 1671. Five years later the St. Charles Mission and the Metabetchouane Trading Post were operating at the mouth of the river on the site of a traditional Indian camp. Now exchanging goods was more convenient for both parties.

The Metabetchouane Centre of History and Archeology and Metabetchouane Trading Post details this period in history. A chart on the wall outlines the value of each European item in terms of beaver pelts. Items sought by the Montagnais had to be portable because of their nomadic lifestyle and had to improve their living conditions in such a harsh environment. These included rifles, powder horns, axes, scythes, hand drills, tin cups, metal pots, blankets, clothing and sail canvas which replaced animal skins on wigwams and long houses. Samples of these are displayed on the rough cut wooden walls inside the centre.

Cultural exchanges were also both desirable and inevitable as the coureurs des bois would winter with the Indians to ensure their own survival. They learned to construct birch bark canoes, toboggans and snowshoes. They lived off the land and survived on native foods that were unknown in Europe at the time like pumpkin, artichokes, maple syrup and moose and beaver meat.

Outside on the grounds is a reproduction of a small church. The original 1849 structure was built by the Hudson Bay Company on the site of Jean de Quen’s original church. A steeple with a cross crowns the rough-cut gray plank walls below. Just to the left of the church is a stone memorial dedicated to De Quen.

The grounds also contain a small powder magazine built some time before 1778. Look for the stone structure with gray wooden shingles and wooden door. Nearby is an A-frame roof covering a dome-shaped stone oven with two cast iron doors. A wigwam covered with sail canvas is also on site.

After touring the grounds, walk or drive through the narrow underpass down towards the water. Near the white gazebo, you find yourself standing on the site of the Hudson’s Bay Trading Post. The French trading post was situated opposite this spot on the other side of the river. We were unable to reach this site as we would have had to pass over private property. The French abandoned the Metabetchouane Trading Post in 1696 but the Hudson’s Bay Company resurrected it between 1768 to 1880 before finally closing it and moving to nearby Mashteuiatsh.

Mashteuiatsh

Present-day Mashteuiatsh, a First Nations Reservation on the shore of Lac St. Jean, is where you can learn about the Montagnais Culture as taught by the Montagnais themselves. While the French had named them Montagnais, they call themselves Pekuakamiulnuatsh or the People of the Shallow or Flat Lake because Lac St. Jean is only about ten feet deep at most.

The museum reflects the nomadic ways of the Pekuakamiulnuatsh and how their lives changed with the seasons. They collected berries in the summer, hunted moose in the fall and fished and trapped animals in the winter. Displays include the various tools used for survival.

A very informative audio helps to put their lifestyle into perspective and how they lived off the land. They transported their worldly goods by toboggan, hunted moose using rifles and fished with the aid of nets. They also assembled V-shaped hunting tents capable of sheltering up to 8 individuals. A portable wood burning stove, obtained by means of trading, provided warmth on those cold winter nights.

Outside on the grounds you can stroll through a forest interpretation trail known as the Nutshimatsh. Here you find local plants, trees and shrubs that were used for shelter, travel (toboggans and snowshoes), food (blueberries, wild cherries, raspberries) and medicines. I felt a sense of peace and tranquility come over me as I walked along these pathways.

Finally, this is the only place where you will find a wooden framed longhouse (shaputuan) that is capable of housing as many as 10 or 12 families wishing to settle in one location for a longer period of time. The shaputuan was approximately 36 feet long and 18 feet wide with a 12-foot high arched sail canvas roof. Warmth was provided during the winter by placing pine branches on the ground in addition to the portable wood burning stove with a chimney extending through the roof.

Continue your visit at the nearby Uashassihtsh Cultural Centre where you see traditional Pekuakamiulnuatsh craftspeople at work. The Pekuakamiulnuatsh were dependant upon the birch bark canoe for their survival and they viewed it as both living and as a source of life. At the cultural centre, they construct birch bark canoes using traditional methods. Two people can construct a canoe in two weeks using an axe or a crooked knife and a few other tools. The final product weighs about 85 lbs and is light enough for two people to carry it over a portage.

Our guide showed us a 20-inch diameter tambourine-like drum fashioned using a leather hide stretched over a circular wooden frame. She indicated that such a drum was a traditional hunting tool. While my first thought was that it would more likely scare the animals away, I could not have been more wrong. The elders would beat this drum and enter a trance-like state. Upon awakening they reported where the best hunting grounds were to be found.

Our guide showed us a 20-inch diameter tambourine-like drum fashioned using a leather hide stretched over a circular wooden frame. She indicated that such a drum was a traditional hunting tool. While my first thought was that it would more likely scare the animals away, I could not have been more wrong. The elders would beat this drum and enter a trance-like state. Upon awakening they reported where the best hunting grounds were to be found.

The Pekuakamiulnuatsh hunted animals of all sizes and then processed the hides into leather. These were tied to and stretched out on wooden frames followed by softening them with bear fat, scraping them using caribou bone tools and finally preserving them using the smoke from an open fire in order to kill the bacteria. The leather was then used for clothing, gloves, moccasins and snowshoes.

Snowshoes were woven from strips of moose leather. An expert craftsman such as the one on site usually requires at least a day to weave a single snowshoe. At the time of our arrival he had just completed a snowshoe whose shape was somewhat reminiscent of a tennis racket at 3 feet long and approximately 20 inches wide, although styles and shapes do vary.

Meat and fish were preserved by being placed on the shelves of an almost conical wooden drying rack whose base was approximately 5-feet in diameter. Bannock, a traditional corn bread, was also available for tasting. I found the taste to be slightly reminiscent to that of regular white bread.

The final stop at the cultural centre was the general store where shelves were stocked with European goods including shortening, lard, baking powder, tea, oil lamps, china plates, cups, hats, clothing and blankets. You also find a number of animal pelts on the counter – beaver, lynx, otter, bear, wolf – suggesting that this was more than just a general store; it was also a trading post. This would appear to be a reproduction of the Hudson’s Bay Trading Post that was moved to Mashteuiatsh from Metabetchouane. I could not confirm that this was the original site of that trading post however.

The final stop at the cultural centre was the general store where shelves were stocked with European goods including shortening, lard, baking powder, tea, oil lamps, china plates, cups, hats, clothing and blankets. You also find a number of animal pelts on the counter – beaver, lynx, otter, bear, wolf – suggesting that this was more than just a general store; it was also a trading post. This would appear to be a reproduction of the Hudson’s Bay Trading Post that was moved to Mashteuiatsh from Metabetchouane. I could not confirm that this was the original site of that trading post however.

Upon exiting the Uashassihtsh Cultural Centre, it is a short drive over to the Church of St. Kateri Tekakwitha. This very modern-looking church is dedicated to the first and only Aboriginal Saint to date. While there has been a church present on site since 1896, this one dates to 1987 and has a First Nations interior décor. The apse features a large crucifix hanging behind the altar flanked by a snowshoe on each side. The hand-carved statues of Mary and Joseph both have a natural wood finish, as does the wooden altar. The Chapel of St. Kateri on the right side of the nave houses her relic, a bone fragment taken from her lower sternum.

After leaving the church, I had a better appreciation for the relationship between the French and the Pekuakamiulnuatsh over the course of history. The French first came into contact with a stone age people yet they would not have survived in this harsh new environment without their assistance. At the same time, the lifestyle of the Pekuakamiulnuatsh was clearly improved through trade with the French. This may in fact be the only true example of peaceful co-existence in the New World where both parties benefited from associating with the other as opposed to being at odds.

If You Go:

Tadoussac is situated on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, 134 miles east of Quebec City.

The Chauvin Trading Post (Poste de Traite Chauvin) is located at 157, rue Bord De L’Eau, just above Tadoussac Bay. Admission is $5.

The Chapelle de Tadoussac is located at rue du Bord-de-l’Eau C.P. 219, just down the street from the Chauvin Trading Post. Admission is free.

Chicoutimi is located on the Saguenay River, 78 miles from Tadoussac.

The Chicoutimi Trading Post site was located in the wooded area between boulevard du Saguenay and rue Price.

Des Biens is on the south shore of Lac St. Jean, 46.8 miles west of Chicoutimi.

The Metabetchouane Centre of History and Archeology and Metabetchouane Trading Post (Centre D’Histoire et D’Archeologie del al Metabetchouane and Poste De Trait Metabetchouane) is located at 243 rue Hébert. Admission is $8.

Mashteuiatsh is approximately 20.8 miles west from Des Biens.

The Native Museum of Mashteuiatsh is located at 1787 Rue Amishk in Mashteuiatsh. Admission is $12.

The Uashassihtsh Cultural Centre (Site de Transmission Culturelle – Uashassihtsh) is located at 1514 Rue Ouiatchouan in Mashteuiatsh. Admission is $15.

The Church of St. Kateri Tekakwitha is located at 1787 Rue Amishk in Mashteuiatsh. Admission is free.

About the author:

Troy Herrick, a freelance travel writer, has traveled extensively in North America, the Caribbean, Europe and parts of South America. His articles have appeared in Live Life Travel, International Living, Offbeat Travel and Travels Thru History Magazines

Photographs:

Diane Gagnon, a freelance photographer, has traveled extensively in North America, the Caribbean, Europe and parts of South America. Her photographs have accompanied Troy Herrick’s articles in Live Life Travel, Offbeat Travel and Travels Thru History Magazines.

.

There are places that tell your body and mind to slow down; to let the world come to you in unhurried steps. Places as beautiful as they are restful, as intrinsically informative as a guided tour yet far from the madding crowd.

There are places that tell your body and mind to slow down; to let the world come to you in unhurried steps. Places as beautiful as they are restful, as intrinsically informative as a guided tour yet far from the madding crowd. Though frequent visitors to the island this trip was a first for we had rented an oceanside cabin at Overbury Farm Resort. Still in the family of the original 1909 homesteader Geraldine Hoffman the farm, which originally gained renown for its eggs, became a resort in the 1930’s and pursues that legacy with manored elegance to this day. Our self-contained, modern cabin was a short forest walk to the gracefully aging and carefully tended manor house on Crescent Point, which owns a magnificent setting and ocean view, set amidst lawn, gardens and trees.

Though frequent visitors to the island this trip was a first for we had rented an oceanside cabin at Overbury Farm Resort. Still in the family of the original 1909 homesteader Geraldine Hoffman the farm, which originally gained renown for its eggs, became a resort in the 1930’s and pursues that legacy with manored elegance to this day. Our self-contained, modern cabin was a short forest walk to the gracefully aging and carefully tended manor house on Crescent Point, which owns a magnificent setting and ocean view, set amidst lawn, gardens and trees.

Owner Norm Kasting told us of a short cut trail through the forest to St. Margaret’s Cemetery and from there to the Capernwray grounds which cut off a good 30 minutes in our trek to the Telegraph Harbour Marina and Pub. As it is our wont to walk and explore we found our way to the cemetery and read, amid the tended lawn setting, how it was donated as a cemetery by early Island resident Henry Burchell in 1927. Its turf was even earlier turned to welcome the remains of a Burchell in 1924. It has since become the final resting place of a number the Overbury Farm-owning family, including pioneering Geraldine Hoffman.

Owner Norm Kasting told us of a short cut trail through the forest to St. Margaret’s Cemetery and from there to the Capernwray grounds which cut off a good 30 minutes in our trek to the Telegraph Harbour Marina and Pub. As it is our wont to walk and explore we found our way to the cemetery and read, amid the tended lawn setting, how it was donated as a cemetery by early Island resident Henry Burchell in 1927. Its turf was even earlier turned to welcome the remains of a Burchell in 1924. It has since become the final resting place of a number the Overbury Farm-owning family, including pioneering Geraldine Hoffman. A gateway opened to the grounds of Capernwray and access to wide grinning Preddy Bay beach where you can wander and explore with tended grounds behind and Vancouver Island panorama before. Capernwray asks that if you wish to enjoy walking their idyllic grounds that you check in at their office behind Preddy Hall. The whitewashed hall stands singularly elegant at the centre of the grounds. And walking their grounds is worth it. There are cared-for lawns with gardens, ponds and visiting Canada Geese, sedate Holstein cattle dotting the greens and views out to Chemainus from whence you can spot the ferry leisurely making its endless crossing. Capernwray offers the opportunity to dine at their hall, which dates back to 1927, along with the students. (Call to reserve 250-246-9440).

A gateway opened to the grounds of Capernwray and access to wide grinning Preddy Bay beach where you can wander and explore with tended grounds behind and Vancouver Island panorama before. Capernwray asks that if you wish to enjoy walking their idyllic grounds that you check in at their office behind Preddy Hall. The whitewashed hall stands singularly elegant at the centre of the grounds. And walking their grounds is worth it. There are cared-for lawns with gardens, ponds and visiting Canada Geese, sedate Holstein cattle dotting the greens and views out to Chemainus from whence you can spot the ferry leisurely making its endless crossing. Capernwray offers the opportunity to dine at their hall, which dates back to 1927, along with the students. (Call to reserve 250-246-9440). A stroll along Foster Point Road to the south of the island takes you past a massive Arbutus tree compelling the road to go around it. Grand as it is it is but second best to another, which rests near the community hall, and is acclaimed the largest Arbutus in B.C. A spider network of paved and unpaved roads offers up miles of leisurely strolling and exploring.

A stroll along Foster Point Road to the south of the island takes you past a massive Arbutus tree compelling the road to go around it. Grand as it is it is but second best to another, which rests near the community hall, and is acclaimed the largest Arbutus in B.C. A spider network of paved and unpaved roads offers up miles of leisurely strolling and exploring. A quiet inland hike can be picked up near the one room school house. Here the solitude of an enveloping forest can hush the busiest of minds.

A quiet inland hike can be picked up near the one room school house. Here the solitude of an enveloping forest can hush the busiest of minds.

The best place to start exploring St. Boniface’s heritage is at the former St. Boniface City Hall, which now houses a tourism office. It is also the starting point of a guided walking tour of old St. Boniface. The red brick building dating back to 1906 is the first item on the tour. Other points of interest include an outdoor sculpture garden beside the tourism office, a Romanesque-revival style brick firehouse built in the early 1900s, a cultural center, a train station built in 1913 that now houses a restaurant, a French-speaking university, and St. Boniface Cathedral. The tour ends on the grounds of Saint-Boniface Museum.

The best place to start exploring St. Boniface’s heritage is at the former St. Boniface City Hall, which now houses a tourism office. It is also the starting point of a guided walking tour of old St. Boniface. The red brick building dating back to 1906 is the first item on the tour. Other points of interest include an outdoor sculpture garden beside the tourism office, a Romanesque-revival style brick firehouse built in the early 1900s, a cultural center, a train station built in 1913 that now houses a restaurant, a French-speaking university, and St. Boniface Cathedral. The tour ends on the grounds of Saint-Boniface Museum. Louis Riel, a controversial figure in Canadian history, was one of Université de Saint-Boniface’s most famed alumni. He is considered a hero by some and a traitor by others. Born in 1844 in St. Boniface, he became a leader of the Métis people, a recognized Canadian aboriginal people of mixed European and First Nations heritage. In the late 1860s unrest grew among the Métis in the Red River area, fearing their livelihood and way of life was threatened by the planned transfer of land from the Hudson’s Bay Company to Canada. In 1869, Riel’s forces took control of Fort Garry, the headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company. From 1869 to 1870, he led a provisional government, a government which would eventually negotiate terms leading to Manitoba becoming a Canadian province and ensuring some protection of French language rights. He is frequently called the “Father of Manitoba”.

Louis Riel, a controversial figure in Canadian history, was one of Université de Saint-Boniface’s most famed alumni. He is considered a hero by some and a traitor by others. Born in 1844 in St. Boniface, he became a leader of the Métis people, a recognized Canadian aboriginal people of mixed European and First Nations heritage. In the late 1860s unrest grew among the Métis in the Red River area, fearing their livelihood and way of life was threatened by the planned transfer of land from the Hudson’s Bay Company to Canada. In 1869, Riel’s forces took control of Fort Garry, the headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company. From 1869 to 1870, he led a provisional government, a government which would eventually negotiate terms leading to Manitoba becoming a Canadian province and ensuring some protection of French language rights. He is frequently called the “Father of Manitoba”. During Riel’s provisional government, his forces arrested men who had plotted to recapture the fort. Thomas Scott, one of the men arrested, was court-martialed and executed by firing squad. The outrage over this incident led the Canadian government to send in forces and regain control of the region. With a bounty on his head, Riel fled to the United States. He returned to Canada, to what is now the province of Saskatchewan, in 1885 to help Métis obtain legal rights. His peaceful petitions produced little result and the Métis rebellion turned violent. Canadian government troops squashed the rebellion. Riel was put on trial for treason. A jury found him guilty but recommended his life be spared. The judge ignored the jury’s recommendation and sentenced Riel to death. He was executed and buried in the cemetery at St. Boniface cathedral. A granite tombstone now identifies his grave, initially marked by a wooden cross.

During Riel’s provisional government, his forces arrested men who had plotted to recapture the fort. Thomas Scott, one of the men arrested, was court-martialed and executed by firing squad. The outrage over this incident led the Canadian government to send in forces and regain control of the region. With a bounty on his head, Riel fled to the United States. He returned to Canada, to what is now the province of Saskatchewan, in 1885 to help Métis obtain legal rights. His peaceful petitions produced little result and the Métis rebellion turned violent. Canadian government troops squashed the rebellion. Riel was put on trial for treason. A jury found him guilty but recommended his life be spared. The judge ignored the jury’s recommendation and sentenced Riel to death. He was executed and buried in the cemetery at St. Boniface cathedral. A granite tombstone now identifies his grave, initially marked by a wooden cross. St. Boniface Cathedral is a major Winnipeg architectural landmark. A fire in 1968 destroyed the 1894 church, leaving its historic stone walls. Behind the facade of the ruined church sits a newer, modern church, a cathedral within a cathedral. Stained glass windows designed by architect Etienne J. Gaboury decorate the new church. Old and new coexist in a quiet and peaceful setting.

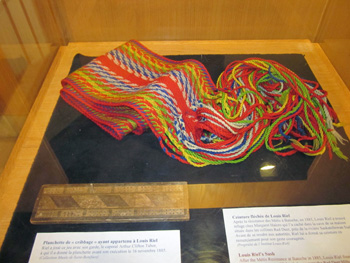

St. Boniface Cathedral is a major Winnipeg architectural landmark. A fire in 1968 destroyed the 1894 church, leaving its historic stone walls. Behind the facade of the ruined church sits a newer, modern church, a cathedral within a cathedral. Stained glass windows designed by architect Etienne J. Gaboury decorate the new church. Old and new coexist in a quiet and peaceful setting. Inside the museum, exhibits reveal the lives and culture of Manitoba’s Francophone and Métis communities. The large collection of artifacts in the Louis Riel exhibit include his trunk, a lock of his hair, his shaving kit, his cribbage board, his moccasins, and the coffin he was originally laid in. Louis Riel’s sash, or ceinture fléchée, is also on display. The ceinture fléchée is a traditional piece of French-Canadian clothing, widely worn in the 18th and 19th centuries, wrapped twice and tied around the waist. Other exhibits include depictions of fur trading life, clothing from the 1800s, artwork, and a chapel. My favourite part was the rooms depicting life in days past, complete with weathered wood beams, hooked rugs on wood plank floors, white metal-framed bed, and cast iron stove.

Inside the museum, exhibits reveal the lives and culture of Manitoba’s Francophone and Métis communities. The large collection of artifacts in the Louis Riel exhibit include his trunk, a lock of his hair, his shaving kit, his cribbage board, his moccasins, and the coffin he was originally laid in. Louis Riel’s sash, or ceinture fléchée, is also on display. The ceinture fléchée is a traditional piece of French-Canadian clothing, widely worn in the 18th and 19th centuries, wrapped twice and tied around the waist. Other exhibits include depictions of fur trading life, clothing from the 1800s, artwork, and a chapel. My favourite part was the rooms depicting life in days past, complete with weathered wood beams, hooked rugs on wood plank floors, white metal-framed bed, and cast iron stove. La Maison Gabrielle-Roy, to the east of old St. Boniface, provides glimpses into the life of a middle class Francophone family in the early 1900s and insight into renowned author Gabrielle Roy. Gabrielle Roy was the recipient of many prestigious literary awards and her books, written in French, were translated into many languages. Roy’s father, a colonization officer, had the house built in 1905. Gabrielle Roy was born in 1909, the youngest of 11 children. The house now functions as a museum and rooms have been restored to look as they would have during Gabrielle’s childhood. The floors are original and the wall colours authentic to what would have adorned the Roy household. The furnishings are not the original Roy family furnishings, but are true to the period. The piano in the parlor is a Bell piano, the same kind that had a prominent place in the Roy family’s life.

La Maison Gabrielle-Roy, to the east of old St. Boniface, provides glimpses into the life of a middle class Francophone family in the early 1900s and insight into renowned author Gabrielle Roy. Gabrielle Roy was the recipient of many prestigious literary awards and her books, written in French, were translated into many languages. Roy’s father, a colonization officer, had the house built in 1905. Gabrielle Roy was born in 1909, the youngest of 11 children. The house now functions as a museum and rooms have been restored to look as they would have during Gabrielle’s childhood. The floors are original and the wall colours authentic to what would have adorned the Roy household. The furnishings are not the original Roy family furnishings, but are true to the period. The piano in the parlor is a Bell piano, the same kind that had a prominent place in the Roy family’s life. Fort Gibraltar is a replica of the original fur trading post built in 1809. The fort was abandoned in 1835 and destroyed by flood in 1852. The replica was built in 1978 to reflect key elements of life in the Red River valley from 1815 – 1821. Inside its wooden walls, costumed interpreters relive daily life of the original inhabitants. They are behind the counter in the general store, forging metal at the blacksmith’s shop, sewing, tending to an outdoor fire, and working in the workshop. Fur pelts hang in the warehouse. A fur press sits along one wall. It was used to press the fur into 90 pound bales for transport in canoe. A voyageur would typically transport two bales at a time.

Fort Gibraltar is a replica of the original fur trading post built in 1809. The fort was abandoned in 1835 and destroyed by flood in 1852. The replica was built in 1978 to reflect key elements of life in the Red River valley from 1815 – 1821. Inside its wooden walls, costumed interpreters relive daily life of the original inhabitants. They are behind the counter in the general store, forging metal at the blacksmith’s shop, sewing, tending to an outdoor fire, and working in the workshop. Fur pelts hang in the warehouse. A fur press sits along one wall. It was used to press the fur into 90 pound bales for transport in canoe. A voyageur would typically transport two bales at a time.

I follow the path to the end of the Lagoon to the seawall at Second Beach. As I walk along the seawall I come to another place that Pauline Johnson liked to visit in the park —Siwash Rock “where the twining roadway branches in two.” This monument of nature stands as a reminder to the Squamish people of one man who lived a good life. The tall pinnacle of rock that rises just off the shore represents Skalsh, a warrior who was turned into stone by Q’Uas the Transformer as a reward for his unselfishness. It is one of the best known legends about a young Indian who was about to become a father and decided to swim in the waters of English Bay to purify himself so his new-born son could start life free of his father’s sins. The gods made Sklash immortal by turning him into a pinnacle of rock. Two smaller rocks representing his wife and son stand in the woods overlooking Siwash Rock.

I follow the path to the end of the Lagoon to the seawall at Second Beach. As I walk along the seawall I come to another place that Pauline Johnson liked to visit in the park —Siwash Rock “where the twining roadway branches in two.” This monument of nature stands as a reminder to the Squamish people of one man who lived a good life. The tall pinnacle of rock that rises just off the shore represents Skalsh, a warrior who was turned into stone by Q’Uas the Transformer as a reward for his unselfishness. It is one of the best known legends about a young Indian who was about to become a father and decided to swim in the waters of English Bay to purify himself so his new-born son could start life free of his father’s sins. The gods made Sklash immortal by turning him into a pinnacle of rock. Two smaller rocks representing his wife and son stand in the woods overlooking Siwash Rock.