Maya Mystery in Mexico’s Yucatan

by George Fery

What we see is not always what we expect whether from nature or man-made. This is often true with archaeological remains of ancient cities or human settlements, when new discoveries shed unexpected light on old finds, leaving question marks in their wake. So, let us have a look at Chichén Itzá, the Maya pre-Columbian city in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, that is a place we thought had been thoroughly explored and visited, at last count by over five thousand people per day, but yet…

The biggest visitor’s draw take place on the spring and autumn equinoxes, when the sun plays with the angles of the northeast stairway of the Kukulcán pyramid, called El Castillo in Spanish. At that time, the course of the sun at sunset projects the shadows of the corners of the pyramid onto the vertical northeast face of the stairway balustrade, giving the visual impression of an undulating serpent slowly crawling down toward its stone head at the bottom of the stairs. Thousands of tourists gather on the Grand Plaza to witness the event. They come to simply share in a common spirit that transcends time and culture. In our age of extraordinary advance in sciences and technologies, unimaginable only twenty years ago, peoples seem to search for “something” beyond their daily lives in a swiftly changing world.

To find out how this remarkable city came to make history in the Yucatán, requires a brief look at why Chichén Itzá became such an important theocratic metropolis. Its history spans from the mid-Classic (600-900AD) to the early part of the Postclassic period (900-1200AD). The ancient city historical record, however, is clouded in uncertainty with often inconsistent description and dates. Help may be found with early Spanish chroniclers and the nine Chilam Balam books written by the Mayas in the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, such as those of the towns of Chumayel, Ixil and Tizimin, among others. The Chilam Balams are collections of myths, prophesies, mythological and ritual texts among other topics. Chilam means together prophet and priest, while Balam stands for jaguar. At its height, Chichén Itzá was a major theocratic center in the lowlands, drawing pilgrims from afar with its sacred well.

From early times, the Mayas traded with cities in central Mexico, exchanging beliefs and inherent in such contacts. Toltec groups migrated sporadically to the Yucatán throughout the sixth centuries and possibly earlier. Their migration to both the west and east coasts of the lowlands intensified in the early tenth century when their objectives shifted from trade to military and political control of the peninsula. Together with the Maya-Chontal, historians call Putún, they came from Ppolè on the Yucatán’s east coast. They then united their forces at Cobá with those of the Toltecs, sixty-two miles away on the connecting sacbeh (white road), to Yaxuná, and thirteen miles from Chichén. From Yaxuná, they conquered Chichén Itzá in 987AD; this event is recorded as “the great descent.” The building of the Kukulcán’s we see today started shortly after their taking possession of the ancient city.

From early times, the Mayas traded with cities in central Mexico, exchanging beliefs and inherent in such contacts. Toltec groups migrated sporadically to the Yucatán throughout the sixth centuries and possibly earlier. Their migration to both the west and east coasts of the lowlands intensified in the early tenth century when their objectives shifted from trade to military and political control of the peninsula. Together with the Maya-Chontal, historians call Putún, they came from Ppolè on the Yucatán’s east coast. They then united their forces at Cobá with those of the Toltecs, sixty-two miles away on the connecting sacbeh (white road), to Yaxuná, and thirteen miles from Chichén. From Yaxuná, they conquered Chichén Itzá in 987AD; this event is recorded as “the great descent.” The building of the Kukulcán’s we see today started shortly after their taking possession of the ancient city.

The Shadow and the Equinox

For the ancient Maya, the pyramid was representative of the four-sided temple-mountain, or fourfold partitioning of the world. The name of the Maya deity before the Toltecs’ Tlaloc, was Cha’ac in Yucatec. Kukulcán, that is Quetzalcoatl in the nahuatl language means “Quetzal Feathered Serpent” is a deity that came with the Toltec capital of Tula, in Mexico’s highlands. The Toltecs brought their own god Tlaloc with similar religious attributes as those of the local Maya god Cha’ak, “the longest continuously worshipped god of ancient Mesoamerica” (Miller & Taube, 1993:59). Tlaloc, like its Maya equivalent, is believed to represent the Creation Mountain. For it is the top of mountains that receive rain first in tropical highlands and holds waters in its caves helped by guardian deities. Furthermore, the pyramid is the cultural apex found in most ancient mythologies, believed to have its inverted counterpart bellow the upward structure or counter-image, in the “otherworld.”

The interface between the bases of both pyramids, is where humans and all life-forms live. This inverse perception of a world below is grounded in the belief that the vegetal world sprouts from beneath the ground. After all, are not the roots pointing down into the earth undeniable proof of nature’s perpetuation of life through its never-ending cycles of birth and rebirth? The symbolism of life’s perpetual renewal is underscored again with the serpent’s iconography that appears on numerous stone stelas, temple columns and painted on ceramics. What is seen is not the animal but its perceived power over life. The shedding of its skin was believed to be the renewal of time and life through nature’s repeated cycles. The allegorical significance of the serpent figure in agrarian cultures’ mythologies, assigns the animal shedding of its skin as its past, to live again another life.

Kukulcán is not cardinally oriented, although mythologically it is believed to sit at the center of time and space. Its corners are aligned on a northeast-southwest axis toward the rising sun at the summer equinox, and its setting point at the winter equinox, making it a monumental sun dial for the solar year. Each of the temple-pyramid’s fifty-two panels seen in the nine terraced steps, equal the number of years of the solar calendar. The pyramid’s nine levels are reminders of the nine steps to Xibalba, the underworld. Above all, Kukulcán is an instrument dedicated to the deities of nature and their role in its alternances such as night-day and life-death. The western and eastern sides of the temple are angled to the zenith sunset and nadir sunrise. The main doorway of the temple at the top of the pyramid opens to the north. The four stairways, one on each side ascending the pyramid, have 91 steps each, equal to 364 steps that, with the temple at the top, total the 365 days of the solar year, the haab’, in Maya. The north stairway is the main sacred path, that of the sun at dawn, and it is on its northeast balustrade that triangular shadows appear at sunset on spring and autumn equinoxes.

Kukulcán is not cardinally oriented, although mythologically it is believed to sit at the center of time and space. Its corners are aligned on a northeast-southwest axis toward the rising sun at the summer equinox, and its setting point at the winter equinox, making it a monumental sun dial for the solar year. Each of the temple-pyramid’s fifty-two panels seen in the nine terraced steps, equal the number of years of the solar calendar. The pyramid’s nine levels are reminders of the nine steps to Xibalba, the underworld. Above all, Kukulcán is an instrument dedicated to the deities of nature and their role in its alternances such as night-day and life-death. The western and eastern sides of the temple are angled to the zenith sunset and nadir sunrise. The main doorway of the temple at the top of the pyramid opens to the north. The four stairways, one on each side ascending the pyramid, have 91 steps each, equal to 364 steps that, with the temple at the top, total the 365 days of the solar year, the haab’, in Maya. The north stairway is the main sacred path, that of the sun at dawn, and it is on its northeast balustrade that triangular shadows appear at sunset on spring and autumn equinoxes.

The Great Plaza, Kukulcán and the Primordial Sea

The Great Plaza that surrounds El Castillo on four sides, was completed during the New Chichén phase (900-1500AD). Symbolically, it represents the “primordial sea of creation” from which, according to Maya tradition, all life sprung at the beginning of time. The plaza’s north side, on which Kukulcán is built, was also the area where major ceremonies took place. It is bordered by the Venus Platform, close to that of the Jaguars and Eagle Warriors, behind which is the massive skull rack, or tzompantli in nahuatl. It is 164 feet long by 40 feet wide and may follow in size the biggest in Mexico-Technochtitlán. On the skull rack was a scaffold-like built of wood poles over the stone structure, on which hundreds of skulls of war captives and sacrificial victims were displayed.

The Great Plaza that surrounds El Castillo on four sides, was completed during the New Chichén phase (900-1500AD). Symbolically, it represents the “primordial sea of creation” from which, according to Maya tradition, all life sprung at the beginning of time. The plaza’s north side, on which Kukulcán is built, was also the area where major ceremonies took place. It is bordered by the Venus Platform, close to that of the Jaguars and Eagle Warriors, behind which is the massive skull rack, or tzompantli in nahuatl. It is 164 feet long by 40 feet wide and may follow in size the biggest in Mexico-Technochtitlán. On the skull rack was a scaffold-like built of wood poles over the stone structure, on which hundreds of skulls of war captives and sacrificial victims were displayed.

On the east side of the Great Plaza is the massive Temple of the Warriors, and the no less important Ball Court to the west, the largest in the Americas – 552 feet long by 300 feet wide, with 20 feet high walls. The theocratic city inner sanctum was the Great Plaza, that was surrounded by a seven feet high wall with a number of guarded entrances, among which is the 980 feet long and 25 feet wide sacbeh.1 or “white road” that leads to the Sacred Well. There are over 34 sacbehobs (sacbeh plural), in Chichén connecting major structures and residential complexes. Most buildings are oriented 17 degrees off true north; Kukulcán is 23 degrees off.

Chichén Itza Spiritual Gateways

There are two spiritual gateways, that are linked to the temple-pyramid, one natural, the other man-made. The first is the huge sacred cenote, or sink hole, called the “Great Well of the Itza.” The name Chichén Itzá in Maya-Chontal, is made up of the words “chi” that means mouth and “chen” for well; while “itz” means sorcerer and “ha” or “á” is for water, that translate as “the mouth of the well of the water sorcerer” (Piña Chan, 1998:32). The Chilam Balam de Chumayel record an earlier name, before the Itza’s arrival, as Uuc Yabnal (“Seven Great Houses”), that is found engraved on door jambs in “Old Chichén.”

The First Spiritual Gateway is the Sacred Well, a large sink hole that was not used for domestic purposes, but for rituals. It is reached by the large elevated sacbeh.1 heading 980 feet northward from the Great Plaza. This sink hole was believed to be the place of contact with the deities of Xibalba, the “place of awe” or underworld, abode of the tantamount Maya god Cha’ak, the powerful Maya god of rain, lightning and thunder. The Sacred Well is oval shaped (164 feet by 200 feet). From its lip to the drop is 79 feet to the water and its depth 65 feet; there is a bed of mud about 20 feet thick at the bottom.

The First Spiritual Gateway is the Sacred Well, a large sink hole that was not used for domestic purposes, but for rituals. It is reached by the large elevated sacbeh.1 heading 980 feet northward from the Great Plaza. This sink hole was believed to be the place of contact with the deities of Xibalba, the “place of awe” or underworld, abode of the tantamount Maya god Cha’ak, the powerful Maya god of rain, lightning and thunder. The Sacred Well is oval shaped (164 feet by 200 feet). From its lip to the drop is 79 feet to the water and its depth 65 feet; there is a bed of mud about 20 feet thick at the bottom.

In one of the rooms of the shrine built on the south side lip of the well, was the temazcal or steam bath in the nahuatl language, to purify sacrificial victims to Cha’ak or Tlaloc. Gifts to the god were precious jade and gold, fine ceramics, jade and lives, as human remains found at its bottom testify. Of forty-two human remains, more than half were younger than twenty and fourteen were younger than twelve years old (Tozzer, 1957:212-213). Offerings in the cenote to the gods Tlaloc or Cha’ak are noteworthy for their origins, particularly gold and mix gold-copper metals (tumbaga), that were not used by the Maya, but imported from lower Central America. Atonement gifts were in reverence to the needs of the time and the demands of the deities. The archaeological record shows that human sacrifices were of both gender and of any age. In time of dire needs, however, such as persistent droughts, a community would sacrifice its best, not the sickly or the maimed. Sacrificial victims had to be able, in their prime and, the younger the better for the gods would not accept anything less.

The socio-economic organization of ancient Maya communities, as that of other ethnic groups at the time, revolved around agriculture. At the Yucatán’s latitude there are only two seasons, which meant two harvests. Hence the Maya religious organization that adhered to a close partnership with nature. The gods and deities from above and below humankind plane were those believed to drive the fundamentals of sun, rain and the vegetal world. Those fundamentals are enshrined in the Maya-K’iche’ sacred book, the Popol Vuh or Book of Counsel, which describes the creation of the universe by the gods who, after failing four times, succeeded in creating humankind out of maize dough.

The “Feathered Serpent” is a mythological deity of the Toltecs found in Late Classic architecture (600-900AD). In Guatemala the deity was called Guqumatz by the Maya-K’iche’, while the Maya-Lacandón refer to it as an evil monstrous snake, the pet of the sun god. Before the Toltecs, the Maya god of agriculture, wind, and storms was Cha’ak, “the longest continuously worshipped god associated with abundance and fertility in ancient Mesoamerica” (Miller & Taube, 1993:59). Kukulcán appears in the mid-Classic Maya period (800-1500AD), as the Vision Serpent.

The serpent sculpted on monuments at Chichén Itzá and other Mesoamerican sites is a metaphor, for it was perceived as it slithers, as the swirls of smoke following self-sacrifice by a member of the nobility or the priesthood. After a self-inflicted wound, a person’s blood would drip on thin sheets of dry bark paper that was then burned. The swirling smoke of the burning bloodstained bark paper was believed to carry the prayers of the supplicant to ancestors and deities, seeking their guidance for living another day in a dangerous world. For ceremonies, copal nodules called pom in Maya-K’iche’, are used instead of human blood. Copal is a tree resin obtained from the sap of the copal tree (protium copal), emblematic of the vegetal world’s “blood.” In the Yucatán today, for Chac Xib Cha’ak ceremonies or “Red Man Cha’ak”, fowls and small mammals may also be sacrificed to plead for rain and a good corn harvest.

The serpent sculpted on monuments at Chichén Itzá and other Mesoamerican sites is a metaphor, for it was perceived as it slithers, as the swirls of smoke following self-sacrifice by a member of the nobility or the priesthood. After a self-inflicted wound, a person’s blood would drip on thin sheets of dry bark paper that was then burned. The swirling smoke of the burning bloodstained bark paper was believed to carry the prayers of the supplicant to ancestors and deities, seeking their guidance for living another day in a dangerous world. For ceremonies, copal nodules called pom in Maya-K’iche’, are used instead of human blood. Copal is a tree resin obtained from the sap of the copal tree (protium copal), emblematic of the vegetal world’s “blood.” In the Yucatán today, for Chac Xib Cha’ak ceremonies or “Red Man Cha’ak”, fowls and small mammals may also be sacrificed to plead for rain and a good corn harvest.

The Second Gateway is the Toltec style I-shaped Great Ball Court is the second spiritual gateway. It is man-made but no less a powerful portal, located on the west side of the Great Plaza. Four temples are associated with the ball court, the Upper and Lower Temples of the Jaguars as well as the North and South Temples. For the ancient Mayas and Toltecs, ritual games played in ball courts were believed to open a portal to the “otherworld” This “gateway” however, could only take place during a ritual fateful game destined to end in sacrifice. The Book of Counsel (Popol Vuh) stresses that the deities of Xibalba in the underworld, did not play unless a ritual contest took place simultaneously above ground. It is only when ritual games were concurrent in this world and the “other” that the interplay between the participants in the two worlds were believed to materialize, that is, open the door to the underworld. Through history, secular and ritual games underline the same need to keep peace and balance within and between communities as well as with gods and deities. Secular games did not involve sacrifice and took place more frequently, with the same intensity as our games today, along with heated betting on teams and players. Essential to ritual games, however, and to a certain extent secular games as well, was the need to keep in check latent antagonism between factions of the same polity, as well as between polities.

The Second Gateway is the Toltec style I-shaped Great Ball Court is the second spiritual gateway. It is man-made but no less a powerful portal, located on the west side of the Great Plaza. Four temples are associated with the ball court, the Upper and Lower Temples of the Jaguars as well as the North and South Temples. For the ancient Mayas and Toltecs, ritual games played in ball courts were believed to open a portal to the “otherworld” This “gateway” however, could only take place during a ritual fateful game destined to end in sacrifice. The Book of Counsel (Popol Vuh) stresses that the deities of Xibalba in the underworld, did not play unless a ritual contest took place simultaneously above ground. It is only when ritual games were concurrent in this world and the “other” that the interplay between the participants in the two worlds were believed to materialize, that is, open the door to the underworld. Through history, secular and ritual games underline the same need to keep peace and balance within and between communities as well as with gods and deities. Secular games did not involve sacrifice and took place more frequently, with the same intensity as our games today, along with heated betting on teams and players. Essential to ritual games, however, and to a certain extent secular games as well, was the need to keep in check latent antagonism between factions of the same polity, as well as between polities.

The Pyramid Within and Balamku’s Cave Below

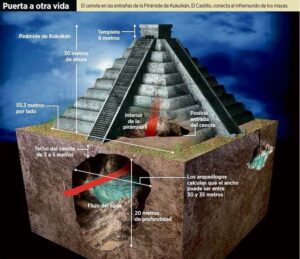

Building larger structures over smaller ones was a common practice in Maya and other ancient Mesoamerican cultures. The reason was that any man-made structure was the product of culture and therefore was believed to be saturated with the ancestral power of those who ordered its construction, together with that of their stone carvers, and could not willingly be destroyed. The pyramid within Kukulcán, discovered by archaeologists in 1958, has a single stairway that faces northeast; it has sixty-one steps and a temple on top with two parallel galleries. There is a triple molding on its façade and a frieze showing a parade of jaguars, shields and two intertwined serpents over its main door. In the antechamber of the inner temple was found a red jaguar that may have served as a throne for the High Priest. On the seat was an offering of a turquoise mosaic disk. The jaguar is painted red on polished limestone; the teeth are made of flint, and there are incrustations of fine jade disks for its eyes and on its body for the animal spots. Architectural similarities between the two pyramids indicate that the one within may also be of Toltec origin, possibly built 650-750AD. Was the “serpent” shadow also seen on the buried structure at spring and autumn equinoxes? Unlikely.

Building larger structures over smaller ones was a common practice in Maya and other ancient Mesoamerican cultures. The reason was that any man-made structure was the product of culture and therefore was believed to be saturated with the ancestral power of those who ordered its construction, together with that of their stone carvers, and could not willingly be destroyed. The pyramid within Kukulcán, discovered by archaeologists in 1958, has a single stairway that faces northeast; it has sixty-one steps and a temple on top with two parallel galleries. There is a triple molding on its façade and a frieze showing a parade of jaguars, shields and two intertwined serpents over its main door. In the antechamber of the inner temple was found a red jaguar that may have served as a throne for the High Priest. On the seat was an offering of a turquoise mosaic disk. The jaguar is painted red on polished limestone; the teeth are made of flint, and there are incrustations of fine jade disks for its eyes and on its body for the animal spots. Architectural similarities between the two pyramids indicate that the one within may also be of Toltec origin, possibly built 650-750AD. Was the “serpent” shadow also seen on the buried structure at spring and autumn equinoxes? Unlikely.

In 1958 a cenote or sink hole was found sixty-five feet beneath Kukulcán, its waters running from north to south. The pyramid seats on a 16-20 feet thick limestone layer above the sink hole’s dome. The discovery, together with a man-made corridor below the cenote, was sealed off from the outside world, probably for lack of resources to further its exploration at the time. The cenote and the cave system were “re-discovered” during the ongoing research project GAM-Gran Acuifero Maya (2016), that expands below the archaeological complex and beyond, including the cenotes Xtoloc, Kanjuyún and Holtún. The cenote below the pyramid is at the center of the Toltec mythical world, its axis mundi. Sink holes, above and below ground, were regarded as gateways to another side of reality, for water was perceived to be the single most important medium for the survival of all life forms. Below Kukulcán’s sink hole, a cave that was also found in 1958, was partially explored in 2018 by the National Geographic’s arqueologists Guillermo de Anda, Ana Celis and their team of investigators from the Great Maya Aquifer Project (GAM). During their investigations was found below the cenote, a 1,500 feet long corridor difficult of access.

In 1958 a cenote or sink hole was found sixty-five feet beneath Kukulcán, its waters running from north to south. The pyramid seats on a 16-20 feet thick limestone layer above the sink hole’s dome. The discovery, together with a man-made corridor below the cenote, was sealed off from the outside world, probably for lack of resources to further its exploration at the time. The cenote and the cave system were “re-discovered” during the ongoing research project GAM-Gran Acuifero Maya (2016), that expands below the archaeological complex and beyond, including the cenotes Xtoloc, Kanjuyún and Holtún. The cenote below the pyramid is at the center of the Toltec mythical world, its axis mundi. Sink holes, above and below ground, were regarded as gateways to another side of reality, for water was perceived to be the single most important medium for the survival of all life forms. Below Kukulcán’s sink hole, a cave that was also found in 1958, was partially explored in 2018 by the National Geographic’s arqueologists Guillermo de Anda, Ana Celis and their team of investigators from the Great Maya Aquifer Project (GAM). During their investigations was found below the cenote, a 1,500 feet long corridor difficult of access.

The archaeologists called the cave Balamkú, that is Maya for “Jaguar God ” for its ancient name is unknown. The black jaguar is a central figure in Mesoamerican and other pan-American mythologies, because of the belief in the animal’s ability to enter and leave the underworld at will, while the spotted jaguar is symbolic of the deities and powers of light. Maya cave ceremonies, especially those that took place in their deepest recess, were bound to rituals performed within the underworld. Those rituals were enacted to symbolically “re-enter the womb” in addition to a sense of rebirth and renewal upon exiting the cave, inherent to initiation. Exploration of the cave system was funded in part by a grant from the National Geographic Society, in cooperation with the University of California at Los Angeles. So far, over 170 ceramic bi-conical censers and other pots were found in seven small rooms carved out of the limestone walls and were identified as those of the Toltec god Tlaloc. The ceramics are dated from the Late Classic (700-800AD) to the Terminal Classic (800-1000AD), contemporaneous with those in the nearby cave at Balamkanché. This important discovery will no doubt help rewrite Chichén Itzá’s history.

In the archaeologist Guillermo de Anda’s opinion, Balamkú seems to be what he called the “mother” of Balamkanchè located 2.5 mile away, since as he puts it “I don’t want to say that quantity is more important than information, but when you see that there are many, many offerings in a cave that is also exceedingly difficult of access, this tells us something” (2017:15). Archaeologists now have the opportunity to answer some of the most perplexing questions that continue to stir controversy among professionals, such as the level of contacts and influence exchanged between Maya highland and lowland cultures, as well as with central Mexico, and perhaps clarify what was going on in the Maya world prior to the building of the first pyramid at Chichén Itzá.

Chichén Yet to be Discovered

There still is a lot to be discovered at Chichén Itzá, since much more is hidden, as work on Balamkú reminds us. Furthermore, excavation programs in the Great Plaza, started in 2009, revealed buried structures that pre-date Kukulcán. By then we already knew about the pyramid within. Puzzling discoveries and wonders are certain to continue. We will visit Chichén Itzá again of course, since this story is only a glimpse of the ancient city’s complex history, while so much more wait to be brought to light. Understanding the “whos” “whys”, “whens” and “hows” of the city’s great past will take a few more “stories” and interpretations in the light of ongoing discoveries.

There still is a lot to be discovered at Chichén Itzá, since much more is hidden, as work on Balamkú reminds us. Furthermore, excavation programs in the Great Plaza, started in 2009, revealed buried structures that pre-date Kukulcán. By then we already knew about the pyramid within. Puzzling discoveries and wonders are certain to continue. We will visit Chichén Itzá again of course, since this story is only a glimpse of the ancient city’s complex history, while so much more wait to be brought to light. Understanding the “whos” “whys”, “whens” and “hows” of the city’s great past will take a few more “stories” and interpretations in the light of ongoing discoveries.

Whether or not sharing the serpent’s shadow during the equinoxes help visitors in their quest for balance in their lives, they will leave the ancient city and return home with fascination and wonder. What else does Chichén Itzá, and its great pyramid hold? And what happened to Kukulcán? After the defeat of Chichén Itzá by the Cocom ruler Unac Ceel of Mayapán in the thirteenth century, Kukukcán moved with the conqueror to the new Maya political epicenter, sixty-five miles to the west…but that is another story.

Credits for Photos & Illustrations

- Equinox Shadow by Fernando Pineyro in postcardemexico.com

- Kukulcan and Temple of Venus georgefery.com

- A World Below georgefery.com

- Chichen Itza Great Plaza georgefery.com

- Sacred Well of Sacrifices georgefery.com

- The Serpent and the Equinox georgefery.com

- The Great Ballcourt georgefery.com

- Two Kukulcans Alberto Ruz Lhuillier, 1998:21

- Gateways to Another Life INAH-GAM in geofisica.com.mx

- Great Plaza Discoveries georgefery.com

Bibliography – References:

Román Piña Chan, 1998 – Chichén Itzá, La Ciudad de los Brujos del Agua

Ralph, L. Roys, 1967 – The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel

Scarborough & D. R. Wilcox, 1991 – The Mesoamerican Ballgame

Linda Schele & Peter Mathews, 1998 – The Code of Kings

Ralph L. Roys, 1965 – Ritual of the Bacabs, A Book of Maya Incantations

Eric S. Thompson, 1970 – Maya History and Religion

Fray Diego de Landa, 1966 – Relación de las Cosas de Yucatan

Clemency Chase Coggins, 1984 – Cenote of Sacrifice

Mary Miller & Karl Taube, 1993 – The Gods and Sybols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya

Linda Schele & David Freidel, 1990 – The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya

Nigel Davies, 1980 – The Toltec Heritage

Robert J. Sharer & Loa P. Traxler, 2006 – The Ancient Maya

Chichen Itza Tours Now Available:

Private tour to Chichen Itza, Valladolid and Ek Balam

VIP Chichen Itza & Coba Private Tour

From Cancun & Riviera Maya: Early-Bird Chichen Itza, Cenote & Valladolid Tour

Chichen-Itza Evening Light Show & Ik Kil Blue Cenote Tours~Also Accessible Tour

About the author:

Freelance writer, researcher, and photographer, Georges Fery (georgefery.com) addresses topics, from history, culture, and beliefs to daily living of ancient and today’s indigenous communities of the Americas. His articles are published online in the U.S. at travelthruhistory.com, popular-archaeology.com, and ancient-origins.net, as well as in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com). In the U.K. his articles are found in mexicolore.co.uk.

The author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies instituteofmayastudies.org Miami, FL, and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org. As well as a member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, NFAA-Non Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthrosassociation.com, and the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu.