by Connie Pearson

by Connie Pearson

I thought I had her figured out. After all, I saw the movie Titanic and the musical The Unsinkable Molly Brown. But this remarkable woman was so much more. Margaret (Molly) Brown died at the age of 65 – the exact age that I am now – but she made such a big splash in her ocean of influence that surviving the sinking of the Titanic was only a small piece of her powerful life story.

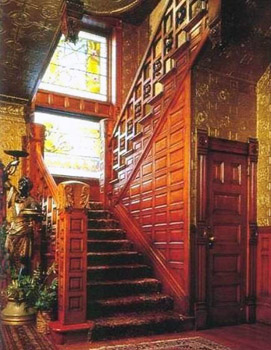

During a recent conference in Denver, my fellow attendees and I were given a 3-hour time period and told to “go out and explore Denver.” I chose to take a taxi from my downtown hotel and visit the Molly Brown House Museum. Dubbed “The House of Lions” because of the imposing lion statues the Browns purchased for the front of the house, it is located at 1340 Pennsylvania Street. Very few of the furnishings and artifacts are original to the time Molly Brown lived there, but careful study of photos made in 1910, have helped Historic Denver, Inc. with their extensive restoration efforts. Visitors have an authentic experience.

During a recent conference in Denver, my fellow attendees and I were given a 3-hour time period and told to “go out and explore Denver.” I chose to take a taxi from my downtown hotel and visit the Molly Brown House Museum. Dubbed “The House of Lions” because of the imposing lion statues the Browns purchased for the front of the house, it is located at 1340 Pennsylvania Street. Very few of the furnishings and artifacts are original to the time Molly Brown lived there, but careful study of photos made in 1910, have helped Historic Denver, Inc. with their extensive restoration efforts. Visitors have an authentic experience.

During the guided tour, it would have been entertaining enough if I had just learned of traits and tendencies that I have in common with Molly Brown. For instance, we’re both considered feisty, and, like her, I play the piano, love to entertain, and work in my church. Green is even our favorite color. She was born in Missouri. I was born in Alabama. Both states are in the Southeastern Conference for college football. Does that make us both Southerners? She once said of herself, “I’m a glutton for knowledge.” What a great way to describe curiosity and a desire to keep learning. Qualities I hold dear.

The trivial threads holding us together end at that point. Molly’s life story, as shared by the docent, unfolded as an amazing inspiration and picture of the power of what one determined woman can accomplish.

The trivial threads holding us together end at that point. Molly’s life story, as shared by the docent, unfolded as an amazing inspiration and picture of the power of what one determined woman can accomplish.

Even though she and her husband, James J. Brown, were millionaires because of a discovery of gold in Leadville, CO, her thoughts were on exposing unfair labor practices she saw in those mines and working in soup kitchens and charity efforts. She worked closely with Denver judge Ben Lindsey in the creation of a national juvenile court system.

In 1901, she attempted to win a seat in the state senate, in spite of a popular saying of the day (one that was strongly supported by her husband): “A woman’s name should appear in the newspaper only 3 times: at her birth, when she gets married, and at her death.” The pressure must have been tremendous, because she withdrew from the race before Election Day. It was no surprise to learn that she was active in the women’s suffrage movement.

In 1901, she attempted to win a seat in the state senate, in spite of a popular saying of the day (one that was strongly supported by her husband): “A woman’s name should appear in the newspaper only 3 times: at her birth, when she gets married, and at her death.” The pressure must have been tremendous, because she withdrew from the race before Election Day. It was no surprise to learn that she was active in the women’s suffrage movement.

Molly Brown was practically thrown into lifeboat #6 as the Titanic was sinking. Immediately after the Carpathia picked up all of the survivors they could find, Molly started helping fellow survivors, some of whom had lost everything. She raised $10,000 from Carpathia passengers before the ship reached New York. A couple of years later, she was helping in relief efforts during World War I.

You will see colorful stained glass windows, ornately-carved woodwork, and anaglypta wall coverings. You will learn that this house had indoor plumbing, electricity, central heat and a telephone long before other homes had these conveniences. But, most of all, you will leave wanting to know more about Margaret Tobin Brown and her indomitable – yes, unsinkable – compassion for others and zeal for life.

You will see colorful stained glass windows, ornately-carved woodwork, and anaglypta wall coverings. You will learn that this house had indoor plumbing, electricity, central heat and a telephone long before other homes had these conveniences. But, most of all, you will leave wanting to know more about Margaret Tobin Brown and her indomitable – yes, unsinkable – compassion for others and zeal for life.

Haunted Denver Evening Pub Tour

If You Go:

Molly Brown House Museum website

Upcoming Events:

Skeletons in the Wardrobe Tea

Saturday, October 31st 11:00 am, 2:00 pm – $24.00 / $18.00 children (6-12)

It’s no secret, Victorians loved Halloween and so do we! The holiday looked a little different back then, though. Do you know what costumes were popular or what games were played? How did the Victorians decorate their homes? Learn the history of Halloween and show off your own ghostly get-up at our spookiest tea of the year! Suitable for ages 8 and up.

A gift shop is behind the house where you can purchase postcards, books and videos, as well as vintage clothing, accessories, toys and games.

About the author:

Connie Pearson is a native Alabamian, wife of 44 years, mother of 3, grandmother of 12. A retired elementary music teacher/former missionary/now budding weight-lifter, travel writer and blogger. www.theregoesconnie.com

Photos are used by permission, courtesy of the Molly Brown House Museum:

House Exterior

Front Hall

Dining Room

Front Parlor

Kitchen

Pfeiffer had a penchant for fighting in the nude, or so it would seem. His first nude encounter happened on June 20, 1863, as a forty-one year-old captain based at Fort McRae, near today’s Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. (The fort has since been flooded by Elephant Butte Reservoir). The captain had taken ill and thought the hot springs, about six miles from the fort near the Rio Grande River, would be beneficial for his malady. He bathed in the curative springs, while his pregnant wife of seven years, Antonita, his adopted daughter Maria, and her attendant Mrs. Mercardo, bathed in a pool nearby. His three-year old son Albert had been left at the fort with servants. Additionally, soldiers accompanied the group to safeguard their bathing at El Ojo del Muerto, the Spring of the Dead.

Pfeiffer had a penchant for fighting in the nude, or so it would seem. His first nude encounter happened on June 20, 1863, as a forty-one year-old captain based at Fort McRae, near today’s Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. (The fort has since been flooded by Elephant Butte Reservoir). The captain had taken ill and thought the hot springs, about six miles from the fort near the Rio Grande River, would be beneficial for his malady. He bathed in the curative springs, while his pregnant wife of seven years, Antonita, his adopted daughter Maria, and her attendant Mrs. Mercardo, bathed in a pool nearby. His three-year old son Albert had been left at the fort with servants. Additionally, soldiers accompanied the group to safeguard their bathing at El Ojo del Muerto, the Spring of the Dead. Pfeiffer’s only thoughts were to save his wife and daughter. With his rifle lying close by, he instinctively leapt for the rifle, running to the safety of the nearby river bank, completely nude. Clothes were the least of his concern. According to the November 1933 issue of The Colorado Magazine, “He was followed by the Indians who shot at him, one of the arrows entering his back with the end coming out in front. In this condition, with the arrow in his back, he ran until he reached an enclosure of rock where he made a halt to rest and defend himself.” Later, he arrived at the fort with an embedded arrow just below his heart, more dead than alive. Still naked, Pfeiffer was barely recognizable as his sunburned skin peeled off in layers. “When the surgeon drew out the arrow from his back, the sun-scorched skin surrounding the wound came off with it, and for days the Captain suffered intense agony and lay for two months at the point of death,” according to the magazine.

Pfeiffer’s only thoughts were to save his wife and daughter. With his rifle lying close by, he instinctively leapt for the rifle, running to the safety of the nearby river bank, completely nude. Clothes were the least of his concern. According to the November 1933 issue of The Colorado Magazine, “He was followed by the Indians who shot at him, one of the arrows entering his back with the end coming out in front. In this condition, with the arrow in his back, he ran until he reached an enclosure of rock where he made a halt to rest and defend himself.” Later, he arrived at the fort with an embedded arrow just below his heart, more dead than alive. Still naked, Pfeiffer was barely recognizable as his sunburned skin peeled off in layers. “When the surgeon drew out the arrow from his back, the sun-scorched skin surrounding the wound came off with it, and for days the Captain suffered intense agony and lay for two months at the point of death,” according to the magazine.

Pfeiffer was so despondent over the loss of his family that he vowed to kill Apaches to avenge their death. It almost became a passion. The Colorado Chieftain newspaper on June 29, 1871, read: “It was a bad day for the Apaches when they killed old Pfeiffer’s family. He made several trips, alone, into their country, staying, sometimes for months, and always seemed pleased, for a few days, on his return. He was always accompanied by about half a dozen wolves in the Apache country. ‘They like me,’ he said once, ‘because they’re fond of dead Indian, and I feed them well.'”

Pfeiffer was so despondent over the loss of his family that he vowed to kill Apaches to avenge their death. It almost became a passion. The Colorado Chieftain newspaper on June 29, 1871, read: “It was a bad day for the Apaches when they killed old Pfeiffer’s family. He made several trips, alone, into their country, staying, sometimes for months, and always seemed pleased, for a few days, on his return. He was always accompanied by about half a dozen wolves in the Apache country. ‘They like me,’ he said once, ‘because they’re fond of dead Indian, and I feed them well.'” The Utes and the Navajos both revered the healing powers of the hot springs, located at modern-day Pagosa Springs, in southwestern, Colorado. The Utes had laid claim to the land generations prior to the Navajo challenge, but shared the springs because of their sacred origins. Then, in late 1866, the Navajo challenged the Utes for control of the springs, fighting for several days to stake their claim. Unfortunately, it ended in a stalemate.

The Utes and the Navajos both revered the healing powers of the hot springs, located at modern-day Pagosa Springs, in southwestern, Colorado. The Utes had laid claim to the land generations prior to the Navajo challenge, but shared the springs because of their sacred origins. Then, in late 1866, the Navajo challenged the Utes for control of the springs, fighting for several days to stake their claim. Unfortunately, it ended in a stalemate.

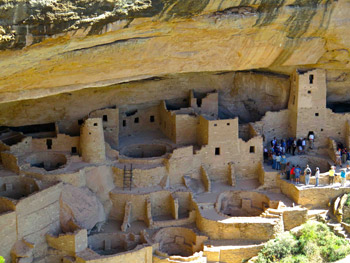

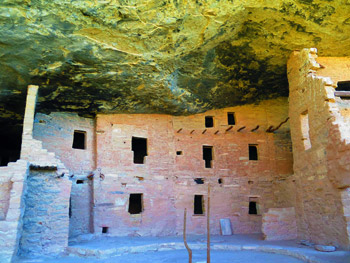

Evidence of settlement on the Colorado Plateau only dates back to AD 550, but signs of human presence on the plateau go back at least 10,000 years to the Paleolithic Age. For much of the known history of these people, they existed as tribes of wandering hunter gathers. Forging for food is easier than farming.

Evidence of settlement on the Colorado Plateau only dates back to AD 550, but signs of human presence on the plateau go back at least 10,000 years to the Paleolithic Age. For much of the known history of these people, they existed as tribes of wandering hunter gathers. Forging for food is easier than farming. The Anasazi are rich in history. What is emerging is from the archeology work is a complex and, somewhat egalitarian, society. They succeeded to thrive for millennium in a sparse land with harsh winters. The archeological evidence of the Anasazi date back to 1200 BC—a time known as the “Basket Making Era” since they had baskets, but no pottery, and lived in camps or caves, surviving off a staple of cultivated squash and corn.

The Anasazi are rich in history. What is emerging is from the archeology work is a complex and, somewhat egalitarian, society. They succeeded to thrive for millennium in a sparse land with harsh winters. The archeological evidence of the Anasazi date back to 1200 BC—a time known as the “Basket Making Era” since they had baskets, but no pottery, and lived in camps or caves, surviving off a staple of cultivated squash and corn.

If you’re coming from Denver, you’ll enjoy the scenic, mountain-carved route along US Highway 160W and US 285S. I drove in from Grand Junction, along US 50. If you can do this drive in the fall, roll your windows down and you can smell the yellow and red leaves bursting in bright patches amongst ever-steady green pines. Carved cliffs of rock will add earthy tones to the pallet, and blue sky might cause you to turn the radio down so as to let the evolving panoramic fill your senses.

If you’re coming from Denver, you’ll enjoy the scenic, mountain-carved route along US Highway 160W and US 285S. I drove in from Grand Junction, along US 50. If you can do this drive in the fall, roll your windows down and you can smell the yellow and red leaves bursting in bright patches amongst ever-steady green pines. Carved cliffs of rock will add earthy tones to the pallet, and blue sky might cause you to turn the radio down so as to let the evolving panoramic fill your senses.

As the vintage blue and white train climbs upstream following the banks of the Arkansas, the canyon walls grow ever closer and higher. Soon a fragile looking suspension bridge comes into view high overhead. It spans the width of the canyon from north to south. From the unobstructed view of an open railroad car, passengers can actually see light between the wooden boards that form the deck of the bridge.

As the vintage blue and white train climbs upstream following the banks of the Arkansas, the canyon walls grow ever closer and higher. Soon a fragile looking suspension bridge comes into view high overhead. It spans the width of the canyon from north to south. From the unobstructed view of an open railroad car, passengers can actually see light between the wooden boards that form the deck of the bridge. Beneath the suspension bridge, the canyon is so narrow and the walls so steep that a place for railroad tracks seemed impossible. The river simply must occupy the entire canyon bottom. But in 1879 a “hanging bridge” was devised and built to allow the tracks to pass through the narrow space suspended above the rushing water. This bridge still serves today.

Beneath the suspension bridge, the canyon is so narrow and the walls so steep that a place for railroad tracks seemed impossible. The river simply must occupy the entire canyon bottom. But in 1879 a “hanging bridge” was devised and built to allow the tracks to pass through the narrow space suspended above the rushing water. This bridge still serves today. It wasn’t a Civil War skirmish; the only one of those fought around here was at Glorietta Pass just south of the New Mexico border. This was a war for territory between two railroads: Colorado’s “baby road,” the narrow gauge, Denver & Rio Grande, and the big, standard gauge, Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe. But, many of the men involved had been soldiers in that bloody war: quite notably the D&RG’s president, General William Jackson Palmer.

It wasn’t a Civil War skirmish; the only one of those fought around here was at Glorietta Pass just south of the New Mexico border. This was a war for territory between two railroads: Colorado’s “baby road,” the narrow gauge, Denver & Rio Grande, and the big, standard gauge, Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe. But, many of the men involved had been soldiers in that bloody war: quite notably the D&RG’s president, General William Jackson Palmer.

Santa Fe seized the entrance to the canyon west of Cañon City cutting off the D&RG for the second time. The outraged D&RG built forts upstream in the canyon to block the rival’s progress. Both sides recruited men well accustomed to the use of firearms – the Santa Fe brought in Bat Masterson with a crew of men from Dodge City. The resulting standoff was widely known as “The Royal Gorge War”.

Santa Fe seized the entrance to the canyon west of Cañon City cutting off the D&RG for the second time. The outraged D&RG built forts upstream in the canyon to block the rival’s progress. Both sides recruited men well accustomed to the use of firearms – the Santa Fe brought in Bat Masterson with a crew of men from Dodge City. The resulting standoff was widely known as “The Royal Gorge War”.