by Wynne Crombie

A rousing beat was coming from the 1820 Meeting House. The door was open and a demonstration of Shaker religious singing was in progress. It was a boisterous rendition of Loch Lomond. My husband Kent and I stepped in to get a closer peek. It reminded us of an American Indian pow-wow.

The guide told us that the music was particularly boisterous to shake sin out of the transgressors. A display of a cradle stood next to a sign that read: “1805 cradle used by Shakers to rock adults to shake out their sins.”

We were at Shakerville, Kentucky outside Lexington and we had come to experience Shaker Life.

The Meeting House interior was free of any central obstructions to provide the Believers plenty of room to conduct their services. It was built to withstand a considerable amount of vibration due to the expressive nature of Shaker worship. Music was a central element of their worship. For much of their history, the Shakers worshipped without instruments.

The village was bustling. Visitors were strolling along the dirt paths; a guided tour was visible in the distance and a horse and wagon ride had just crept up behind us.

We were ready to begin our discovery of a way of life that was simplicity itself.

Shakers started arriving at Pleasant Hill somewhere around 1805. As early as 1816 they were producing enough surpluses of brooms, preserves, packaged seeds and other products to begin regular trading trips to New Orleans.

By the Mid-1850s Shakerville (as it was called) was home to approximately 600 Shakers occupying 250 buildings and almost 2800 acres of land. The Civil War and Industrial Revolution took a heavy toll and the community dissolved in 1910. In 1961, it was reestablished as a non-profit educational entity.

Kent and I had some thirty-four surviving buildings to explore. These are structures without fanfare, simple lines without curves. The Shakers were self-sufficient. They took what they had and made do. Crops were grown, and the seeds saved for the next year’s harvest. They made their own furniture and wove their own cloth. Houses were painted either pale yellow or white. Stone chimneys graced both sides of the houses.

One of the original bath houses still exists. They were constructed for each gender. Near-by was the Post Office where both Shakers and local residents received mail.

We took time out to dine at the restaurant, The Trustees’ Table. Their motto is: Dine with straight from the garden ingredients. Bowls of seasoned relish, a selection of hot vegetables and homemade bread come with each entrée. Kent and I chose, Fried Green Tomatoes, as an appetizer. Smothered Pork Loins over cornbread dressing were our entrees. ($20). Another enticing entrée was Mrs. Kremer’s Fried Chicken. ($21.95).

In addition to dining, you can spend the night at The Inn. Visitors can choose from guest rooms, suites and private cottages. Rooms are furnished with Shaker reproduction furniture, original hardwood floors and magnificent views of the surrounding countryside.

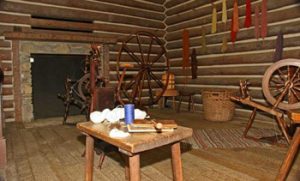

Beds¸ single, double, and low trundle, were manufactured on site. The Shakers used raw local materials. A necessary function was the production of cloth and garments from wool and vegetable fibers produced on the farm. Examples… Linen, worsted, and linsey-woolsey were on display. The latter was in popular demand for the making of slave clothing. An interesting sight was an array of five Shaker brooms hanging on pegs. When the light is just right, they cast interesting shadows on the wall.

Water was pumped by horse power from a spring to the 19,000-gallon reservoir in the Water House. The water was then fed, via gravity, to the kitchens and wash houses in the Village.

Society was divided into families from 50 to 100 members. Each family had its own dwelling house.

There is one remaining privy or, as the Shakers called it, a Necessary. Instead of a trench, the privy had a clean-out vent on the back wall.

As we moved from building to building we discovered more looms, spinning wheels. homemade furniture and kitchen utensils. The finished products were all made by hand. A display of clothes showed shapeless gowns in grayish-blues and maroon. Clothes in muted blues and maroons were hanging on pegs. The white bonnets were shapeless; the long skirts formless and drab. There was little difference between the shoes and stockings worn by men and women.

Also intriguing were the ubiquitous stone fences. Our guide, Bertha explained that about four layers of stones are piled one upon another. The top layer is composed of stones laid on their sides. This is called, “coping.” The purpose was twofold: to weigh down the fence and to keep the cattle in. In addition to the stone fences, property was also marked with white wooden fences with horizontal slats.

Today, Shaker Village is very much a village at work. Farmers, historians, naturalists and many others work from growing the organic garden, to managing prairie habitat, caring for important artifacts, restoring historic buildings and building an apiary, real work happens here!

After exploring the village you can head over to The Farm to meet the animals and out into The Preserve to explore 3,000 acres of farmland.

Admission grants you access to a full day of discovery filled with self-guided and staff-led tours, talks, music, demonstrations, exhibitions, hands-on activities and more.

Jump on board the horse-drawn wagon or take a hay ride around The Historic Centre every weekend, from April through October.

The site is home to the country’s largest private collection of original 19th century buildings.

It is open daily from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm Admission $10. (Ages 13 and up).

Photo credits:

All photos by Wynne Crombie

About the author:

Wynne Crombie has a master’s degree in Adult Education. Her work has appeared in: Alaskan Airline Magazine, Travel and Leisure, Travel Thru History, Dallas Morning News, Senior Living, Stars and Stripes, Birds and Blooms, Italy Magazine (UK) Get Lost (Au) Catholic Digest, Country Woman, Quilt Magazine, and Chicago Parent. She has taught in the United States and with the DOD at Aviano AFB, Italy and Berlin. (It was in Berlin that she met her husband of 55 years) They have retired to Lexington, Kentucky and love it.

I got to visit Smarty Jones (the 2004 Kentucky Derby and Preakness winner who’s currently residing in Pennsylvania). He came up to his stable door. How I wanted to pet him, but I was told that he has a tendency to bite, so I couldn’t. He was let out by one of the staff so I could pose with him, though for legal reasons involving the horses’ images, visitors can only show their photos offline to others.

I got to visit Smarty Jones (the 2004 Kentucky Derby and Preakness winner who’s currently residing in Pennsylvania). He came up to his stable door. How I wanted to pet him, but I was told that he has a tendency to bite, so I couldn’t. He was let out by one of the staff so I could pose with him, though for legal reasons involving the horses’ images, visitors can only show their photos offline to others. The Kentucky Derby is the longest consecutive running sporting event in America. Since 1875, 136 of these annual horse races have been run at Churchill Downs through 2010. Seeing it on TV all these years didn’t prepare me for the draw it would have on me while visiting. I stayed there some four hours, and could’ve spent much more easily as I took three tours and visited the on site museum. It’s one of the few places in the world that I felt glued to because of the ambience, the tradition, and incredible history that makes up the 160 acre complex. I am not usually a fan of guided tours, but I found their guides to be quite engaging.

The Kentucky Derby is the longest consecutive running sporting event in America. Since 1875, 136 of these annual horse races have been run at Churchill Downs through 2010. Seeing it on TV all these years didn’t prepare me for the draw it would have on me while visiting. I stayed there some four hours, and could’ve spent much more easily as I took three tours and visited the on site museum. It’s one of the few places in the world that I felt glued to because of the ambience, the tradition, and incredible history that makes up the 160 acre complex. I am not usually a fan of guided tours, but I found their guides to be quite engaging. I was about to go into the museum when I heard a 90 minute Behind The Scenes Tour was about to happen. I felt led to take it, and I’m glad I did! Fans get to see such places as the clubhouse and locker room for the male jockeys, as well as find out about how these athletes must all be the same weight for the Kentucky Derby (126 pounds, but 121 if they ride a filly). It’s done by adding extra padding until the weight is reached. I also found out that jockeys wear several pairs of goggles around their eyes, so if one pair gets wet or soiled, they can de-layer for a clean one. We also got to go to the press area, Millionaires’ Row seating, and the track announcer’s booth. Believe me, this 90 minutes goes by too fast!

I was about to go into the museum when I heard a 90 minute Behind The Scenes Tour was about to happen. I felt led to take it, and I’m glad I did! Fans get to see such places as the clubhouse and locker room for the male jockeys, as well as find out about how these athletes must all be the same weight for the Kentucky Derby (126 pounds, but 121 if they ride a filly). It’s done by adding extra padding until the weight is reached. I also found out that jockeys wear several pairs of goggles around their eyes, so if one pair gets wet or soiled, they can de-layer for a clean one. We also got to go to the press area, Millionaires’ Row seating, and the track announcer’s booth. Believe me, this 90 minutes goes by too fast! After a day of admiring racing horses, a great place to relax for a drink is the Old Seelbach Bar in downtown Louisville. The Seelbach Bar has many pictures of race horses hanging on its early 1900’s restored walls, including some Kentucky Derby winners. Did you know that F. Scott Fitzgerald sipped bourbon here? The hotel itself was a setting for his novel The Great Gatsby, a place where the fictional hometown girl Daisy Buchanan may have actually gotten drunk because of her forthcoming sham wedding to Tom Buchanan!

After a day of admiring racing horses, a great place to relax for a drink is the Old Seelbach Bar in downtown Louisville. The Seelbach Bar has many pictures of race horses hanging on its early 1900’s restored walls, including some Kentucky Derby winners. Did you know that F. Scott Fitzgerald sipped bourbon here? The hotel itself was a setting for his novel The Great Gatsby, a place where the fictional hometown girl Daisy Buchanan may have actually gotten drunk because of her forthcoming sham wedding to Tom Buchanan!