Mdina, Malta

by Ilene Springer

They call it “The Silent City,” but Mdina (pronounced Medina which is Arabic for city) in the tiny Mediterranean country of Malta is anything but silent on this April day. I’m pushing my way through throngs of people – all about to enter one of the two magnificent gates of this fortified city. It’s Mdina’s annual flower and pageantry festival, marking the beginning of spring and also commemorating the warlike history of this alluring walled settlement.

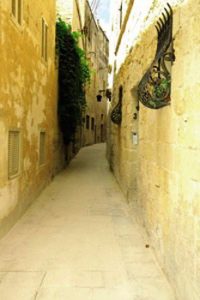

Mdina, as beautiful as it is with its high limestone walls, narrow curved streets and panoramic views of the rest of Malta beneath it, is not about beauty; it’s about survival. In fact, all of Malta is about survival over one conqueror after another through the centuries – the Romans, the Arabs, the Turks, the French – and the Maltese are proud of it. The pageantry festival – with its battle re-enactments – is one way of showing off this stubborn pride.

Mdina, as beautiful as it is with its high limestone walls, narrow curved streets and panoramic views of the rest of Malta beneath it, is not about beauty; it’s about survival. In fact, all of Malta is about survival over one conqueror after another through the centuries – the Romans, the Arabs, the Turks, the French – and the Maltese are proud of it. The pageantry festival – with its battle re-enactments – is one way of showing off this stubborn pride.

But the festival is about spring, too. Even before I enter the Vilhena Gate, I’m taking in the scent of hundreds of flowers lining the walls that lead to the gate. Row upon row of perfect white roses. Bay leaves grace the main gate and the pedestals in St. Publius Square – my first destination. I’m told that all the flowers are locally grown.

And to the right, below the stone bridge that I’m walking on, is Mdina’s orange grove in all its wild splendor. I remember that off to the left side there’s a tennis court below; this strikes me as kind of incongruous – a civilized game of tennis on the left and a wild, untouched orange grove on the right. But in a way – these are the two sides of Maltese culture – tame and untamed in one land.

Today, however, the tennis court has been transformed into an archery range. Archery plays a significant role in the architecture of Mdina. The narrow curved streets within the city’s walls were built to prevent a straight arrow from ever reaching its mark. But nowadays, the alleyways are known for their little surprises around the corner – a café or small thicket of potted olive trees.

Today, however, the tennis court has been transformed into an archery range. Archery plays a significant role in the architecture of Mdina. The narrow curved streets within the city’s walls were built to prevent a straight arrow from ever reaching its mark. But nowadays, the alleyways are known for their little surprises around the corner – a café or small thicket of potted olive trees.

Meanwhile, I’m still trying to get through the gate with my Maltese friend Carmen who has accompanied me, and getting a little irritated that it’s taking some time to turn and twist through the crowds. But the Maltese are experts on throwing a festival. They even give you something to do while you’re waiting to get to the main event.

On the stone floor off to the right, a “medieval family” sits playing a game with little pegs and coins. Their game board is drawn with chalk on the stone. The folks are decked out in red, green and brown hats, tunics and tights for the men, and matching frocks for the lasses. They go on with their game – as if they belong there – oblivious to the camera flashes going off around their faces. The thought strikes me: These people take their role in this festival very seriously. And it won’t be the last time I think that today.

Historians believe that Mdina – the oldest inhabited place on Malta – was first settled by the Phoenicians 4000 years ago. Then, according to tradition, in 60 AD the Apostle Paul lived here after he was shipwrecked on the islands. In medieval times, it was known as Citta’ Notabile’ – The Noble City because it was home to many of the Norman, Sicilian and Spanish overlords during the 12th century. Many of these people, in fact, became the famed Knights of Malta. Mdina’s many palaces – secreted behind high walls – are still home to the descendants of these noblemen and their families. Today, for the festival, Mdina’s stone balconies are draped with flowering plants.

Historians believe that Mdina – the oldest inhabited place on Malta – was first settled by the Phoenicians 4000 years ago. Then, according to tradition, in 60 AD the Apostle Paul lived here after he was shipwrecked on the islands. In medieval times, it was known as Citta’ Notabile’ – The Noble City because it was home to many of the Norman, Sicilian and Spanish overlords during the 12th century. Many of these people, in fact, became the famed Knights of Malta. Mdina’s many palaces – secreted behind high walls – are still home to the descendants of these noblemen and their families. Today, for the festival, Mdina’s stone balconies are draped with flowering plants.

Carmen tells me an interesting tale about a balcony here. In 1798, the French took over Mdina. When the Maltese finally wrested back their city a couple years later, they threw the French commander off of one of these balconies; which one depends on who’s telling you the story.

Finally, we’re inside the gate and making our way past the dungeons – that were really used as dungeons – toward a crowd in the square. I’m straining to see between all these tall people and parents holding up kids and – finally, I see what’s there: the famous Maltese falcons. I’ve never seen real falcons before, and they come in several different sizes and regal colors of blue and red. Their handlers wear gloves to avoid being clawed and the birds are tethered to their owners’ wrists. Later on, we learn, they will let the birds fly!

But the best part for me is when I sneak my hand (I’m allowed) into a box with a 14-day old baby falcon. He’s white and fuzzy with very large feet, but he can only flap around and screech, surprisingly loudly. I’m amazed that the trainers let children (and me) touch the baby bird and take photos. “Touch gently” is the only restriction.

But the best part for me is when I sneak my hand (I’m allowed) into a box with a 14-day old baby falcon. He’s white and fuzzy with very large feet, but he can only flap around and screech, surprisingly loudly. I’m amazed that the trainers let children (and me) touch the baby bird and take photos. “Touch gently” is the only restriction.

Now, forget about the 1941 movie with Humphrey Bogart. Here’s the real story behind the Maltese falcon. In 1530, the Knights of Malta, after being deeded the islands by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles, agreed to an annual symbolic rent of one Maltese falcon which served as a protective bird of prey for the Roman empire.

As I’m (politely) shoved away from the Maltese falcons so other people can take a look, my eye is caught by several young men, dressed in white rags, with their ankles chained to each other. They turn out to be actors posing as slaves who were bought and sold in the square. I look at one man’s face and I think he’s got terrible acne on one cheek. Then I see another man with a similar boil-like infection on his face. I realize this represents some kind of skin disease from back then – or bruises resulting from injuries inflicted on the slaves. I find myself staring until Carmen and I are distracted by something else.

There’s the sound of drums coming down the main street. Knights with full armor (how did they ever wear this stuff in the heat of the summer?), spears and chained face masks are marching to some destination in Mdina where they will re-enact a medieval battle that surely took place centuries ago in this city. They look real and menacing. They’re not clowning around. But they march out of our sight and we don’t actually get to see the fight in all its fake bloody glory.

But what amazes me is how close the bystanders can get to the actors. There are no police in sight, no barricades fencing people off from the actors. All this lends to a reality that you don’t get elsewhere.

But what amazes me is how close the bystanders can get to the actors. There are no police in sight, no barricades fencing people off from the actors. All this lends to a reality that you don’t get elsewhere.

We’re hungry now, but not for medieval food. Carmen and I feel like splitting a tuna baguette – which is a typical light Maltese meal. There are many cafes and restaurants in Mdina, but they’re all unusually crowded because of the festival.

Carmen leads me to the front of a line in the Fontanella Tearooms – famous for its chocolate cake and spectacular views of Malta 200 meters below its tables and chairs. I tell Carmen I don’t feel like waiting in line, and she says we don’t have to. Taking my hand, my 69-year-old friend sneaks us over to an empty table.

“Carmen, we can’t just do that,” I tell her, looking back at the queue we just avoided.

“Well, we just did,” she says and makes herself comfortable.

Ah, a good ending to an entertaining and enlightening festival. Carmen is very Maltese. Just like Mdina, she’s a survivor.

More Information:

Visit Malta (Mdina) – The Official Tourism Site for Malta and Gozo www.visitmalta.com

About the author:

Ilene writes on travel; and on health and wellness for cats, dogs and their human companions. Ilene recently moved from the US to Malta, and Mdina is one of her favorite places in the world. Visit her blog at An-American-in-Malta.com

Photo Credits:

Mdina city walls photo by photosforyou from Pixabay

All other photos by Ilene Springer and Heike Lauer (photo of man in costume).