by Lesley Hebert

I was standing on the slopes of an Indonesian volcano, covered in mud, trying to remember how exactly I came to be there.

I cast my mind back to my teen years when I read a fascinating book about the magical beauty of Bali. Buried in my subconscious, Bali resurfaced forty years later when I saw a travel agent advertising Balinese tour packages, and promptly added it to my bucket list. When my husband and I eventually booked a trip to Bali, we decided to include a side excursion to the smaller neighbouring island of Lombok.

I remembered standing on a Balinese beach staring west across the strait towards the setting sun. I saw the perfect volcanic cone of Lombok’s Mount Rinjani, the second highest mountain in Indonesia, floating in the misty distance between the ocean and the sky, and wondered what fascinating discoveries awaited. As the sun set, the dim shape of the mountain darkened and assumed an air of intriguing mystery.

I remembered standing on a Balinese beach staring west across the strait towards the setting sun. I saw the perfect volcanic cone of Lombok’s Mount Rinjani, the second highest mountain in Indonesia, floating in the misty distance between the ocean and the sky, and wondered what fascinating discoveries awaited. As the sun set, the dim shape of the mountain darkened and assumed an air of intriguing mystery.

Arriving in Lombok, I discovered a lovely tropical island that rivalled Bali in its beauty. However, while Bali is a crowded tourist mecca, Lombok is a quiet, unspoiled natural destination more suited for surfers and snorkelers.

Bali is Hindu while Lombok is predominantly Muslim. Instead of Bali’s ornately carved temples you see the unadorned domes of Lombok’s mosques, and instead of the tinkling chimes of temple bells you hear the chanting of the muezzin’s call to prayer.

As a woman I was concerned about the dress code on the island. However, the locals did not appear to be particularly devout, many being what my tour guide referred to as “three time” Muslims who pray on only three occasions: birth, marriage and death. Consequently, the majority of women do not observe the extreme dress codes of some Islamic countries.

Nevertheless, I decided to dress conservatively. So when our driver came to pick us up for a private island tour I was demurely dressed in a long, loose Balinese batik skirt and soft ballet slippers.

Suitably attired, I sat in the van admiring our driver’s skill as he manoeuvred through flocks of motor scooters, many with whole families perched on them clutching a week’s worth of groceries. We drove around the coast enjoying vistas of deserted beaches and distant islands, and as we crossed the countryside we saw rice farmers winnowing grain by hand and a family gleaning peanuts from a harvested field.

Our guide drove us to the foot of Mount Rinjani and casually suggested that we might want to “walk to the waterfall.” It sounded as if he was proposing a pleasant afternoon stroll. He certainly did not drop any hints about the suitability of my attire for the suggested “walk” as he introduced us to the young man who would escort us.

Our guide was a little under five feet tall and slightly built. As he stood smiling at us in ragged khaki cut-offs and carrying a worn backpack I estimated that he was probably in his early twenties, although his small stature, casual dress and open smile gave the impression that he was much younger.

Our guide was a little under five feet tall and slightly built. As he stood smiling at us in ragged khaki cut-offs and carrying a worn backpack I estimated that he was probably in his early twenties, although his small stature, casual dress and open smile gave the impression that he was much younger.

Our excursion began with an easy, pleasant walk along a canal. Our young guide explained that this was part of an irrigation system built by the Dutch in the nineteenth century when Lombok was part of the Dutch East Indies. Built to carry water down to the rice fields, the canal also provided water for the nearby villages as well as public bathing and laundry facilities. My husband was intrigued to see some women washing clothes on the far bank. He joked that he would love to see me washing my clothes in a stream and I gave a suitably ironic reply.

This easy path turned out to be the deceptive beginning of a challenging mountain hike. It had rained the day before and as we left the canal to begin our climb we came to a steep, slick slope of oozy brown mud. There were no steps or handrails. The only things to hold on to were frail-looking twigs and clumps of grass.

Because I shoes were more appropriate for sliding around on a dance floor than climbing a mudslide, I faced an impossible challenge. Every time I took a step up the slope, my feet lost their grip and I slid back. There were no solid branches to hold onto and my skirt twisted around my knees, preventing me from taking decent strides.

My husband climbed to the top of the slope and tried to pull me up. He succeeded in getting me halfway up before he lost his grip, leaving me to skeeter back down, getting thoroughly coated with mud in the process.

“The hell with modesty,” I announced, and tucked the hem of my mud-soaked skirt into the legs of my underwear to gain more freedom of movement. As I did so, I turned around to look at our guide, only to see him wielding a machete which he had just pulled from his backpack.

It fleetingly occurred to me that perhaps he was about to hack me to pieces for violating Islamic dress codes. But instead of attacking me he used the machete to cut steps into the slick mud of the hillside. Finally able to get some purchase with my feet I reached for my husband’s hand while our guide pushed me up from below. Petrified that if I slipped down again I would crush the poor wee fellow to death, I made a supreme effort and finally made it to the top.

We then followed a narrow path clinging to the hillside. Trying to avoid vertigo I looked away from the steep drop to my left and concentrated on the hillside to the right. Oddly, I noticed porthole-like apertures spaced at regular intervals along the way. I wondered what they were but was so busy concentrating on my footing that I never bothered to ask.

Finally, we arrived at the waterfall and I heaved a sigh of relief. Until, that is, I found out that this was the first falls, Sindang Gila. We were only at the halfway point and would be continuing to the second falls, Tiu Kelep.

Finally, we arrived at the waterfall and I heaved a sigh of relief. Until, that is, I found out that this was the first falls, Sindang Gila. We were only at the halfway point and would be continuing to the second falls, Tiu Kelep.

While we were taking a break, I used the opportunity to clean off the generous coating of caked-on mud which covered me from the waist down, trying to ignore my husband’s delight at seeing me wash my clothes in a stream.

The next part of the trek was a fascinating encounter with a nineteenth century Dutch water engineering project. We climbed a long cement staircase to a “bridge” which was actually an aqueduct covered with cement slabs spaced a foot apart. As I stepped from one slab to the next I could see water rushing through the channel below. I became dizzy and made it to the far side clinging to the handrail for dear life.

On the far side of the aqueduct our guide showed us a lock designed to direct the water from the mountain into designated channels to irrigate different farming areas in the valley below. After about an hour’s hike we crossed a fast-flowing, boulder-strewn stream (which was quite a challenge considering my footwear) and arrived at the second falls which were truly spectacular. Tiu Kelep means “flying water” and the falls did literally fly out and away from the hillside before crashing down into the pool at their feet.

On the far side of the aqueduct our guide showed us a lock designed to direct the water from the mountain into designated channels to irrigate different farming areas in the valley below. After about an hour’s hike we crossed a fast-flowing, boulder-strewn stream (which was quite a challenge considering my footwear) and arrived at the second falls which were truly spectacular. Tiu Kelep means “flying water” and the falls did literally fly out and away from the hillside before crashing down into the pool at their feet.

Our return journey followed the stream we had crossed earlier to the viaduct and down to the canal way. Our guide jumped down into the canal and beckoned us to follow him into a dark, cavernous tunnel.

Standing up to my waist in cold, rapidly flowing water, I fought to stay upright, to avoid hitting my head on rocky outcrops above, and to prevent my loosely fitting shoes from washing away. The uneven cement surface beneath the water had broken away in places, leaving only deep holes spanned by reinforcing bars which we used as balance beams. As I stared into the darkness I realized that this cool, dank tunnel was lit by soft, green light filtering through clumps of emerald ferns growing around regularly spaced holes. In an “aha” moment, I realized these were the hillside portholes I had noticed on the way up.

It took about 20 minutes to walk through the emerald twilight to the end of the tunnel. We climbed out of the canal and continued back through the forest to the visitors’ centre to meet our driver. As we drove away, I treasured unforgettable memories of walking across an aqueduct, spelunking in a water tunnel, and receiving the ultimate compliment from our wonderful little guide:

“Lady, you have heart!”

Private Tour: Amazing Waterfalls of Lombok

If You Go:

Footwear should be sturdy enough for clambering over rocks and suitable for walking through mountain streams. Sturdy non-leather sandals without socks are probably best.

Locals believe that bathing in the pool below Tiu Kelep will add years to your life. If you want to do this, you will need to wear your bathing suit as there are no changing facilities. If you take a towel, carry it in a small back pack rather than a loose bag which you could lose in the canal.

Getting there:

International flights arrive at Denpasar (Ngurah Rai) airport in Bali.

There are two options to get to Lombok. The first is the fast ferry, which takes about two and a half hours. The second is the Indonesian national airline, Garuda, named after the mythical bird that carried the Hindu god Vishnu.

Since it is only a half-hour flight from Denpasar to Lombok this might seem the better choice. However, with an hour’s pre-boarding wait time, security checkpoints and the usual wait at baggage claim total travel time is probably similar. Also, while we had no problems with our flight, I later discovered that Garuda is not approved by European travel agents, who generally book clients on the ferry.

Hiking and Trekking Mount Rinjani Lombok Island Indonesia

About the author:

Lesley Hebert is a graduate of Simon Fraser University. Now retired from teaching English as a second language in the classroom, she teaches ESL to international students via Skype. She also writes on-line articles which reflect a lively, inquiring mind and a love of travel, language, history and culture. Read more of Lesley’s articles at http://www.infobarrel.com/Users/HLesley

Photos by Mike Hebert

Sunset View of Mount Rinjani from Bali

Deserted beach in Lombok

Totally covered in mud!

The first waterfall, Sindang Gila

The Second Waterfall, Tiu Kelep (Flying Waters)

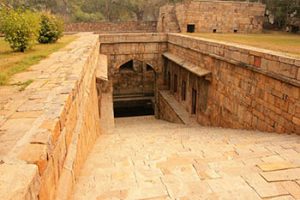

3) Gandhak Ki Baoli

3) Gandhak Ki Baoli

The city of Agra in North India is synonymous with the Taj Mahal, the apogee of Mughal architecture in India. The Mughal Empire was founded by Babur in 1526, a descendent of Timur (Tamerlane) and Genghis Khan. Babur reigned from 1526-1530. He was succeeded by his son Humayun. But the Mughal Dynasty truly flourished under the rule of the emperors who followed Humayun, his son Akbar (1556-1605), Akbar’s son Jahangir (1605-1627), and Akbar’s grandson Shah Jahan (1628-1658), known as the builder of the Taj Mahal.

The city of Agra in North India is synonymous with the Taj Mahal, the apogee of Mughal architecture in India. The Mughal Empire was founded by Babur in 1526, a descendent of Timur (Tamerlane) and Genghis Khan. Babur reigned from 1526-1530. He was succeeded by his son Humayun. But the Mughal Dynasty truly flourished under the rule of the emperors who followed Humayun, his son Akbar (1556-1605), Akbar’s son Jahangir (1605-1627), and Akbar’s grandson Shah Jahan (1628-1658), known as the builder of the Taj Mahal. On a hot, summer day in August, with temperatures reaching 100F, we traveled to Agra from New Delhi in a rented car with driver. This is one of the best ways to go to Agra in the hot months as taxis such as these are air conditioned and one can travel in relative comfort. Our first stop was at Sikandra, the mausoleum of Emperor Akbar, about 10 kilometers from Agra city center. Considered as the greatest Mughal emperor, he was the most secular minded royalty and a patron of the arts, literature, philosophy and science. Akbar himself laid out the plans for his own tomb, selected an appropriate site and even started building it. His son Emperor Jahangir finished building the tomb in 1613.

On a hot, summer day in August, with temperatures reaching 100F, we traveled to Agra from New Delhi in a rented car with driver. This is one of the best ways to go to Agra in the hot months as taxis such as these are air conditioned and one can travel in relative comfort. Our first stop was at Sikandra, the mausoleum of Emperor Akbar, about 10 kilometers from Agra city center. Considered as the greatest Mughal emperor, he was the most secular minded royalty and a patron of the arts, literature, philosophy and science. Akbar himself laid out the plans for his own tomb, selected an appropriate site and even started building it. His son Emperor Jahangir finished building the tomb in 1613. The hallmark of Mughal architecture in India is in the use of red sandstone and marble. We entered the mausoleum complex through a red sandstone gateway, with four minarets in each corner, immediately bringing to mind the Taj Mahal. There are four gateways into the complex but only one is in use now. A broad, paved plaza like walkway leads to the tomb. Magnificent in its look, the tomb is a five story red sandstone building, carved with glazed tiles and colorful stones. The eye catching mosaic patterns that cover the gateway and the tomb entrance embody the essence of Mughal design showcasing elaborate stone inlay work, calligraphy, tile work, painted stucco and white marble.

The hallmark of Mughal architecture in India is in the use of red sandstone and marble. We entered the mausoleum complex through a red sandstone gateway, with four minarets in each corner, immediately bringing to mind the Taj Mahal. There are four gateways into the complex but only one is in use now. A broad, paved plaza like walkway leads to the tomb. Magnificent in its look, the tomb is a five story red sandstone building, carved with glazed tiles and colorful stones. The eye catching mosaic patterns that cover the gateway and the tomb entrance embody the essence of Mughal design showcasing elaborate stone inlay work, calligraphy, tile work, painted stucco and white marble. At around 7 am next morning, we reached the Taj Mahal. In the early morning quiet, we had an easy time of buying tickets and then we headed towards the main entrance gateway to the Taj. I could feel the palpable excitement in the air as we waited to get in. One first views the Taj through the dark entrance way and I remembered my first visit all those years ago. The Taj is one monument I feel that exceeds the expectations of the viewer no matter how many times they have seen it.

At around 7 am next morning, we reached the Taj Mahal. In the early morning quiet, we had an easy time of buying tickets and then we headed towards the main entrance gateway to the Taj. I could feel the palpable excitement in the air as we waited to get in. One first views the Taj through the dark entrance way and I remembered my first visit all those years ago. The Taj is one monument I feel that exceeds the expectations of the viewer no matter how many times they have seen it. The tomb complex stands on the southern banks of the River Yamuna and took twenty years to be completed. It is made of white marble inlaid with semi-precious stones that form intricate designs using the pietra dura technique. There are verses from the Quran, inscribed in calligraphy on various sections of the complex including its arched entrances. Like at Sikandra, the Taj too is situated in a four square Mughal paradise garden, on its northernmost end and on a raised marble platform. The four decorative minarets on each corner lean away slightly so that in the event of an earthquake they do not fall on the main structure. Both Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal are interred here and we see their highly decorated marble cenotaphs directly below the main dome. Both these are false tombs and the real tombs are underground and cannot be viewed by the public.

The tomb complex stands on the southern banks of the River Yamuna and took twenty years to be completed. It is made of white marble inlaid with semi-precious stones that form intricate designs using the pietra dura technique. There are verses from the Quran, inscribed in calligraphy on various sections of the complex including its arched entrances. Like at Sikandra, the Taj too is situated in a four square Mughal paradise garden, on its northernmost end and on a raised marble platform. The four decorative minarets on each corner lean away slightly so that in the event of an earthquake they do not fall on the main structure. Both Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal are interred here and we see their highly decorated marble cenotaphs directly below the main dome. Both these are false tombs and the real tombs are underground and cannot be viewed by the public.

Soon it was time to leave and move on to the next historic site on our itinerary, the Agra Fort, also known as the Red Fort of Agra. Emperor Akbar began building this massive red sandstone fort in 1565 and it was completed with further additions by Emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan. Predominantly built as a military structure, Shah Jahan constructed several white marble palaces within the premises. It too is a UNESCO World Heritage Site designated so in the same year as the Taj.

Soon it was time to leave and move on to the next historic site on our itinerary, the Agra Fort, also known as the Red Fort of Agra. Emperor Akbar began building this massive red sandstone fort in 1565 and it was completed with further additions by Emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan. Predominantly built as a military structure, Shah Jahan constructed several white marble palaces within the premises. It too is a UNESCO World Heritage Site designated so in the same year as the Taj. We walked around the fort in the blinding August midday heat, strangely unperturbed, feeling ourselves being transported to the Mughal glory days. We strolled through marble pavilions and red sandstone hallways, stopping to admire the elaborate and intricate carvings. The Agra Fort is a superb example of Indo-Muslim architecture with Persian influences. This is seen in the floral and geometric designs that cover the walls, the archways, and in the intricate jali (perforated stone and latticed screens) patterns and the balconies that overlook the Yamuna River and the Taj Mahal. In the final years of his life, Shah Jahan and his daughter Jahanara Begum were imprisoned here in the tower known as Musamman Burj by his son Emperor Aurangzeb when he came to power in 1658. It is said that he spent his last days looking out at the mausoleum of his beloved Mumtaz Mahal.

We walked around the fort in the blinding August midday heat, strangely unperturbed, feeling ourselves being transported to the Mughal glory days. We strolled through marble pavilions and red sandstone hallways, stopping to admire the elaborate and intricate carvings. The Agra Fort is a superb example of Indo-Muslim architecture with Persian influences. This is seen in the floral and geometric designs that cover the walls, the archways, and in the intricate jali (perforated stone and latticed screens) patterns and the balconies that overlook the Yamuna River and the Taj Mahal. In the final years of his life, Shah Jahan and his daughter Jahanara Begum were imprisoned here in the tower known as Musamman Burj by his son Emperor Aurangzeb when he came to power in 1658. It is said that he spent his last days looking out at the mausoleum of his beloved Mumtaz Mahal.