Japan: The Battle for Okinawa

by Robert Hale

April 1, 1945… Easter Morning.

There would be no eggs to hunt today; no greetings of, He is Risen!”

Resurrection was not the order of the day. Not on this Easter Day, 1945

References to “Heaven” and “Resurrection” would give way to “give ‘em hell,” and “kill the bastards!” It was obvious that religious services would be held for only the dying and the dead – and then, only for those on our side!

A quarter of a million men were about to die.

No one scheduled a noon family Easter feast. And, for the next 82 days there would be nothing but war! A terrible war!

…The Battle of Okinawa begins!

It was called “Operation Iceberg.” The island would eventually resemble, not an iceberg, but a blazing hell-on-earth! No hymns of joyous praise were to be heard.

Instead, screams of the injured and dying, explosions of rockets and bombs; while of bullets, blasts of grenades, cries of the dying – those were the sounds of that Easter Morning.

In those 82 days of living hell 38,000 American soldiers and marines would be killed or counted as missing in action. The Japanese would lose 107,000 killed, plus more than 23,000 who sealed themselves in caves and took their own lives; 10,800 Japanese soldiers were captured. Civilian deaths are estimated at 142,000.

For the first time in World War II the Japanese were defending Japanese territory!

The Japanese hardly regarded Okinawans as “Japanese,” and certainly not as equals. For sure, the island belonged to the Japanese. It was a vital part of their empire. It was a crucial gate protecting the homeland and that empire. This day the protection was being threatened by gigantic numbers of allied forces.

The Battle of Okinawa would become the defining moment for the Empire of Japan. From here the full force of American air and sea power would be hurled against the nation that began it all on December 7, 1941. More than a half million people would die before American forces wrenched Okinawa from the grip of Japan.

It was a “grip from Hell!” It was grip that lasted nearly three months.

From April 1 until June 21, 1945 the fighting for the island went on, day and night. There was no let up; there was no “time out” for rest, or food, or medical care. There was no pause to collect the dead and re-assemble. For nearly three months it was one continuous deadly explosive battle. It was shell against shell; gun against gun; man against man! In many cases it was simply fist against fist; strangle-hold against stranglehold!

On the morning of June 21, 1945 members of the Sixth Marine Division – George Company, 22nd Regiment – raised the Stars and Stripes. It was over.

Today the Pacific Ocean lives up to its name.

Japan and the United States are at peace; they are close allies; they are good friends. They no longer hunt the hills and trails for each other. They no longer have fingers on triggers, or strongholds in gun sights. Today Japanese and American tourists walk the land marks together, frequently engaged in friendly helpful conversations.

I walked a few of those once bloody paths. I saw a collection of unused, and now ineffective, bombs, shells, and torpedoes. I walked among the graves of Americans, Canadians, British and Japanese. I wasn’t alone.

Bob Crismond was a teenager – 18, if that! – when American forces stormed the shores of Okinawa in 1945.

Now on a warm autumn day Crismond returns to Okinawa for the first time since that historic battle. It has been six and a half decades since Crismond last saw this island. Today it is peaceful here, with rain clouds forming at sea. In 1945 there was hell on this island.

The air was filled with exploding shells, grenades and bullets. There were earth-shattering explosions of artillery shells from US warships firing over the heads of our invading troops. Flamethrowers began their relentless destruction of cave emplacements, wiping out guns, munitions and men. There were hand-to-hand encounters, close-quarter grenade tossing, and even pistol shootouts!

At sea there were Japanese kamikaze planes diving and exploding into American ships. There were screams of the wounded and the dying.

Amidst all of that horror young Bob Crismond was driving a landing vehicle. From his ship off shore he brought in troops and supplies; he returned to his ship with the wounded and the dead. Bob saw those flamethrowers; he watched as Japanese pilots slammed their planes and their lives into the decks of American ships. All around that young man was death.

Was Bob Crismond scared?

“I was just doing what I had to do.”

“I wasn’t close enough to be scared. I had a job to do, and I was busy with that. But, I could see it, and I could hear it. Sometimes I just stopped my boat and watched.”

Bob Crismond never came under attack by the Japanese. He was able to get close to the action.

“When we got here, the battle was raging, and for a while I just watched. It was like watching a movie.”

Bob pointed out where his ship was located in the bay, and where his service boat came and went. He talked of kamikaze attacks, of flamethrowers, of grenades and shell explosions, and of the constant rattle of the machine guns.

Bob knew the Allied forces would prevail. We had just too many men, too much fire power, too many battle and supply ships to not win the battle for Okinawa. Yet, the battle took a lot longer and certainly far more lives than American commanders had anticipated.

This battle was ultimate moment for Japanese military leaders. This was the first invasion of their land and they knew if they did not repulse the enemy victory was not going to the rising Sun! If Okinawa could not be safely defended the Japanese homeland could well be next. Defend they did.

Invading Japan for the first time cost the Americans incredibly high causalities. Okinawa turned out to be the costliest battle in the history of the United States. It ranks as one of the deadliest battles in all recorded history. In addition, the Okinawans and the Japanese who lived on the island joined thousand of soldiers in committing suicide rather than submitting to “American barbarism,” an idea fostered by Japanese leadership as a morale boaster.

I asked Bob Crismond if, at any time, he felt the Allied troops would withdraw in the face of fanatical Japanese forces.

“Didn’t give that one thought. None of us even considered that a possibility.”

And today? Did Crismond have any special emotions about visiting his “hell on earth” war experience?

“No. Nothing special. I just want to see it like any other curious tourist would.”

Bob Crismond was not “just any other tourist.” He was there; he helped get the war closer to victory.

Was he scared? “No. Maybe I was too young to be scared. And, I had that job to do; I was busy with that. I could see it and I could hear it. That was it.”

While some American visitors talked in hushed tones, Japanese tourists were virtually silent. Someone in out groups suggested we understand the mass suicide of Japanese defenders more clearly than does the present generation of Japanese visitors.

Perhaps.

Can anyone truly understand? I asked Bob Crismond if it made sense to him.

“I think we were too busy to try to understand it all. We just wanted it to end.”

It ended, finally. The victors of Okinawa, who assumed they’d become the invaders of mainland Japan, didn’t have to go there after all.

“Two Big Bombs” fell on Japan, and it was over.

Today, the grass is green; the sea is rolling and white capped. The fragrance of salt sea fills the air; so do hushed voices. Many sentences go unfinished; many questions are not answered. Some moments become simply moments of reflection.

Those moments are called “pilgrimages.”

If You Go:

♦ en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Okinawa

Photo credit:

Okinawa Peace Memorial by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas

About the author:

Freelance writer, Bob Hale is a former Chicago radio and TV broadcaster.

We next arrive at the Great Wild Goose Pagoda, a religious complex built about 652,AD on the city’s southern edge. Silver morning mists shroud its peaceful manicured gardens as Hanson regales us with this sanctuary’s legend, “During a severe famine, Buddha miraculously provided flocks of wild geese to feed starving worshipers…” Over 300 Buddhist monks were once housed in 2000 little rooms here; nowadays, forty live here.

We next arrive at the Great Wild Goose Pagoda, a religious complex built about 652,AD on the city’s southern edge. Silver morning mists shroud its peaceful manicured gardens as Hanson regales us with this sanctuary’s legend, “During a severe famine, Buddha miraculously provided flocks of wild geese to feed starving worshipers…” Over 300 Buddhist monks were once housed in 2000 little rooms here; nowadays, forty live here.

Just when we thought it couldn’t get any more captivating we arrive at Xian’s Grand Opera House, a huge dinner theatre. Soon, white-clad servers deliver basket-after-steaming-basket of tiny, mouthwatering dumplings. Wielding our chopsticks enthusiastically and washing each luscious tidbit down with cold Chinese beer, we ooh and ahh delightedly over these intricate handmade creations, decorative tops signifying each filling: duck, broccoli, pumpkin, but the most electrifying experience was yet to come…

Just when we thought it couldn’t get any more captivating we arrive at Xian’s Grand Opera House, a huge dinner theatre. Soon, white-clad servers deliver basket-after-steaming-basket of tiny, mouthwatering dumplings. Wielding our chopsticks enthusiastically and washing each luscious tidbit down with cold Chinese beer, we ooh and ahh delightedly over these intricate handmade creations, decorative tops signifying each filling: duck, broccoli, pumpkin, but the most electrifying experience was yet to come… Hanson continues, “Ascending the throne at age13, Qin unified feudal kingdoms and established China’s first dynasty in 221 BC. Seven hundred thousand artisans worked on his mausoleum for decades before his death, never finishing it. His son eventually continued the work, as his father had wished.”

Hanson continues, “Ascending the throne at age13, Qin unified feudal kingdoms and established China’s first dynasty in 221 BC. Seven hundred thousand artisans worked on his mausoleum for decades before his death, never finishing it. His son eventually continued the work, as his father had wished.” Expecting natural terracotta earthen tones, I’m surprised to learn that hair, eyebrows, faces and hands had then been hand-painted in life-like colours: pink flesh, white eyeballs, black hair. Yellows and scarlet covered Emperor’s robes; green, soldiers’ trousers. Inspired, my hubby bargains for an entire clay regiment to guard our sun room plants back home.

Expecting natural terracotta earthen tones, I’m surprised to learn that hair, eyebrows, faces and hands had then been hand-painted in life-like colours: pink flesh, white eyeballs, black hair. Yellows and scarlet covered Emperor’s robes; green, soldiers’ trousers. Inspired, my hubby bargains for an entire clay regiment to guard our sun room plants back home. At last, we enter into that bright air-conditioned pit over a football field and a half in size. Scarcely believing what we were seeing, we witness the twentieth century’s premier archeological discovery…

At last, we enter into that bright air-conditioned pit over a football field and a half in size. Scarcely believing what we were seeing, we witness the twentieth century’s premier archeological discovery… Hanson observes, “Soldiers and horses have been carefully reassembled from collapsed rubble; the colours have mostly faded.” From each warrior’s facial expression, including wrinkles on the generals, we imagine their different personalities. Last of all, we pause thoughtfully at the humble well’s site, the place that had started worldwide notoriety.

Hanson observes, “Soldiers and horses have been carefully reassembled from collapsed rubble; the colours have mostly faded.” From each warrior’s facial expression, including wrinkles on the generals, we imagine their different personalities. Last of all, we pause thoughtfully at the humble well’s site, the place that had started worldwide notoriety.

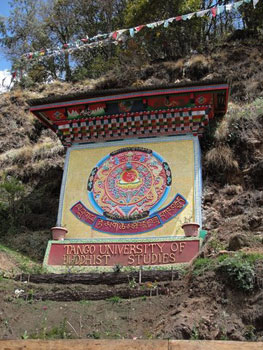

We were on our way to Tango Goemba, a few miles north of the capital, Thimpu. Two flashes, one yellow and one scarlet, darted across the path just in front of us in close succession. Tashi stopped in his tracks. ‘Ssh.’ We followed his gaze, and saw the two small birds on a branch just off to our left. ‘Long-tailed minivets,’ he said. ‘The red one is the male. It’s auspicious to see them together.’

We were on our way to Tango Goemba, a few miles north of the capital, Thimpu. Two flashes, one yellow and one scarlet, darted across the path just in front of us in close succession. Tashi stopped in his tracks. ‘Ssh.’ We followed his gaze, and saw the two small birds on a branch just off to our left. ‘Long-tailed minivets,’ he said. ‘The red one is the male. It’s auspicious to see them together.’ As we approached Tango Goemba, we saw a printed paper sign stuck on a brightly-painted wall: (REQUEST) PLEASE COME IN NATIONAL DRESS. INFORMAL DRESSED ARE NOT ALLOWED LA. It seems that the final ‘la’ takes the edge off any instruction or statement, making it polite. I looked down at my dirty jeans and sweatshirt, but Tashi assured me that the sign only applied to locals. The dogs settled down to rest in front of the monastery entrance.

As we approached Tango Goemba, we saw a printed paper sign stuck on a brightly-painted wall: (REQUEST) PLEASE COME IN NATIONAL DRESS. INFORMAL DRESSED ARE NOT ALLOWED LA. It seems that the final ‘la’ takes the edge off any instruction or statement, making it polite. I looked down at my dirty jeans and sweatshirt, but Tashi assured me that the sign only applied to locals. The dogs settled down to rest in front of the monastery entrance. ‘He is the seventh reincarnation of the fourth desi of Bhutan’, Tashi said. A desi is a spiritual leader. ‘His previous incarnation died in 1830. We are very lucky to see him.’

‘He is the seventh reincarnation of the fourth desi of Bhutan’, Tashi said. A desi is a spiritual leader. ‘His previous incarnation died in 1830. We are very lucky to see him.’ Many stories are told about the Divine Madman’s exploits. One day, a crowd his followers asked him to perform one of the magic feats he was famous for.

Many stories are told about the Divine Madman’s exploits. One day, a crowd his followers asked him to perform one of the magic feats he was famous for. We were blessed by a monk who tapped our heads with two ten-inch plastic phaluses. Since we’re not too bothered about fertility at this point in our lives, we wished for health for our grandson and any grandchildren we may have in the future. Just as we left the temple, I received a text message from my daughter: ‘Your beloved grandson has just walked his first two steps!’

We were blessed by a monk who tapped our heads with two ten-inch plastic phaluses. Since we’re not too bothered about fertility at this point in our lives, we wished for health for our grandson and any grandchildren we may have in the future. Just as we left the temple, I received a text message from my daughter: ‘Your beloved grandson has just walked his first two steps!’

Midway through the dinner, the Maharaja extended his royal invitation to me and my family to be honored guests of his palace. I was absolutely delighted with the offer. A fortnight after the Navaratri festivities, I booked a flight to Ahmedabad and travelled onwards to Gondal by road. By the time we reached Gondal’s magnificent Orchard Palace, it was late evening and dusk had already descended here. I was informed by the palace’s caretaker that the Maharaja was out of town and would be back in a day’s time.

Midway through the dinner, the Maharaja extended his royal invitation to me and my family to be honored guests of his palace. I was absolutely delighted with the offer. A fortnight after the Navaratri festivities, I booked a flight to Ahmedabad and travelled onwards to Gondal by road. By the time we reached Gondal’s magnificent Orchard Palace, it was late evening and dusk had already descended here. I was informed by the palace’s caretaker that the Maharaja was out of town and would be back in a day’s time. During his rule, the residents of Gondal were exempt from paying taxes as he evolved an innovative land revenue system. To make Gondal self-sufficient in livestock, he introduced animal husbandry while to improve the agricultural sector, extensive irrigation network was developed, which brought even the wastelands surrounding Gondal under the ambit of modern agriculture. The Maharaja’s visionary outlook ensured that even those with very little academic background too were also offered meaningful employment with the setting up of technical schools that imparted training on domains like carpentry, mechanics, surveyors, painters and engineers.

During his rule, the residents of Gondal were exempt from paying taxes as he evolved an innovative land revenue system. To make Gondal self-sufficient in livestock, he introduced animal husbandry while to improve the agricultural sector, extensive irrigation network was developed, which brought even the wastelands surrounding Gondal under the ambit of modern agriculture. The Maharaja’s visionary outlook ensured that even those with very little academic background too were also offered meaningful employment with the setting up of technical schools that imparted training on domains like carpentry, mechanics, surveyors, painters and engineers. However, the best was yet to come viz-a-viz the Royal Garages about which I had heard so much from my Gujarati friends at Kolkata. As I was ushered in to the garage compound by my guide, I was downright stupefied by the huge collection of vintage cars which were stationed in individual sheds. This was easily one of the greatest collection of vintage cars in the whole of Asia. The collection ranged from the 1910 New Engine to the more elegant 1940-50s Cadillacs as well as a few truly impressive American cars of the 50s. The best part of the Royal Garages was the remarkable collection of horse drawn carriages, which was inclusive of the Victorian and Shetland carriages.

However, the best was yet to come viz-a-viz the Royal Garages about which I had heard so much from my Gujarati friends at Kolkata. As I was ushered in to the garage compound by my guide, I was downright stupefied by the huge collection of vintage cars which were stationed in individual sheds. This was easily one of the greatest collection of vintage cars in the whole of Asia. The collection ranged from the 1910 New Engine to the more elegant 1940-50s Cadillacs as well as a few truly impressive American cars of the 50s. The best part of the Royal Garages was the remarkable collection of horse drawn carriages, which was inclusive of the Victorian and Shetland carriages. No visit to the Naulakha Palace is ever complete without a visit to the exclusive Palace museum which showcases the rare collection of silver caskets which I was told were used to carry messages and gifts for the erstwhile Maharaja of Gondal.

No visit to the Naulakha Palace is ever complete without a visit to the exclusive Palace museum which showcases the rare collection of silver caskets which I was told were used to carry messages and gifts for the erstwhile Maharaja of Gondal.