by Tatiana Claudy

“Saint Petersburg is a window through which Russia looks at Europe,” stated Francesco Algarotti, a Venetian poet. [1] Fyodor Dostoyevsky called this city “the most intentional town” because Peter the Great, the Russian monarch, ordered it to be built on a swampy terrain in the delta of the Neva River to guard Russia from its adversaries – Swedish King Karl XII and his mighty navy. [2] The time will come when for its richness, splendor, and sophistication the city will be called “the Northern Palmyra,” and numerous visitors will admire grandeur of the capital of the Russian Empire. Yet sometimes the city’s first buildings, constructed the 18th century, are overshadowed by more magnificent palaces of the 19th century. Today I am going to visit these first buildings – the architectural marvels and silent witnesses of the early history of the city.

The foundation of Saint Petersburg is enveloped in legends. According to one, on May 16, 1703, Tsar Peter surveyed the Hair Island and pronounced: “Here the city will be built!” Suddenly an eagle flew above his head, and this has been considered a good omen. According to another legend, at first wooden gates have been constructed, and an eagle descended on them. Tsar Peter took the eagle in his hands and walked through the gates of his newly-founded city.

The first building of the new city was Peter the Great’s cabin put up by soldiers in three days on the banks of the Neva River. This construction does not resemble a royal residence – it is a one-story wooden house built from square beams, painted red and designed to imitate a brick wall, according to a Dutch architectural style. Its four-slope green roof has been originally decorated with a wooden model of a mortar to show that the house belonged to a military man. I visited this palace, one of the smallest in the world (12 meters long, 5,5 meters wide, and 2,72 meters high), and was amazed to see the humble dwelling of a Russian tsar. The cabin itself is off-limits for tourists, but they can peek through barred windows to see two main rooms – Tsar Peter’s study and the dining room.

The first building of the new city was Peter the Great’s cabin put up by soldiers in three days on the banks of the Neva River. This construction does not resemble a royal residence – it is a one-story wooden house built from square beams, painted red and designed to imitate a brick wall, according to a Dutch architectural style. Its four-slope green roof has been originally decorated with a wooden model of a mortar to show that the house belonged to a military man. I visited this palace, one of the smallest in the world (12 meters long, 5,5 meters wide, and 2,72 meters high), and was amazed to see the humble dwelling of a Russian tsar. The cabin itself is off-limits for tourists, but they can peek through barred windows to see two main rooms – Tsar Peter’s study and the dining room.

In the center of the study, there is a massive oak table with a carved chess-board (Tsar Peter loved to play chess and checkers). On the table, there is a pipe belonged to the tsar, a brass candleholder for three candles, a brass inc-pot, and a map. On the wall, we can see Peter the Great’s portrait representing him at the time when he started to build a new capital. Another interesting object is the chair made from pear-tree wood by Peter the Great who was a skilful carpenter. The cabin has no heating because it was designed as a summer dwelling. Tsar Peter lived there for several weeks before his departure for the Northern War and, upon his return, a stone palace was built for him (Winter Palace). To protect the cabin from the elements, a case has been constructed around it. Today, inside this case, tourists can see not only the cabin, but also “the grand-father” of the Russian navy – a wooden boat made by Tsar Peter. The cabin was not only the first house and first palace erected in the new city – it became one of the first Russian museums when Peter the Great signed an order to preserve it for the posterity.

In the center of the study, there is a massive oak table with a carved chess-board (Tsar Peter loved to play chess and checkers). On the table, there is a pipe belonged to the tsar, a brass candleholder for three candles, a brass inc-pot, and a map. On the wall, we can see Peter the Great’s portrait representing him at the time when he started to build a new capital. Another interesting object is the chair made from pear-tree wood by Peter the Great who was a skilful carpenter. The cabin has no heating because it was designed as a summer dwelling. Tsar Peter lived there for several weeks before his departure for the Northern War and, upon his return, a stone palace was built for him (Winter Palace). To protect the cabin from the elements, a case has been constructed around it. Today, inside this case, tourists can see not only the cabin, but also “the grand-father” of the Russian navy – a wooden boat made by Tsar Peter. The cabin was not only the first house and first palace erected in the new city – it became one of the first Russian museums when Peter the Great signed an order to preserve it for the posterity.

While the original building of Tsar Peter’s Winter Palace does not exist anymore, his Summer Palace has been restored and turned into a museum. In 1710, Domenico Trezzini (an Italian architect) created this royal residence according to the Petrine Baroque architectural style. This two-story building resembles a Dutch nobility house of the 18th century –windows are divided into squares and outer walls are adorned by 29 bas-reliefs with allegoric scenes glorifying the Russian navy and its victories. The palace stands on the bank of the Fountanka River, and guests of the tsar arrived by boats. The royal family lived here from May till October. The palace’s collection includes many genuine items, for instance, Tsar Peter’s watch with a compass and the quilt made by his wife, Catherine (future Empress Catherine I). I believe that the most interesting room is Tsar Peter’s workshop: being skilful in14 trades, he daily worked with a turning lather. The workshop was Tsar Peter’s favorite room, and only selected people had an honor to meet with the tsar there. The Summer Palace is located in one of the most romantic places of Saint Petersburg, the Summer Garden, designed to resemble the Versailles and decorated with marble sculptures, fountains, flower beds, and pavilions.

While the original building of Tsar Peter’s Winter Palace does not exist anymore, his Summer Palace has been restored and turned into a museum. In 1710, Domenico Trezzini (an Italian architect) created this royal residence according to the Petrine Baroque architectural style. This two-story building resembles a Dutch nobility house of the 18th century –windows are divided into squares and outer walls are adorned by 29 bas-reliefs with allegoric scenes glorifying the Russian navy and its victories. The palace stands on the bank of the Fountanka River, and guests of the tsar arrived by boats. The royal family lived here from May till October. The palace’s collection includes many genuine items, for instance, Tsar Peter’s watch with a compass and the quilt made by his wife, Catherine (future Empress Catherine I). I believe that the most interesting room is Tsar Peter’s workshop: being skilful in14 trades, he daily worked with a turning lather. The workshop was Tsar Peter’s favorite room, and only selected people had an honor to meet with the tsar there. The Summer Palace is located in one of the most romantic places of Saint Petersburg, the Summer Garden, designed to resemble the Versailles and decorated with marble sculptures, fountains, flower beds, and pavilions.

Now I am going to the Basil Island to visit the first stone building of Saint Petersburg, the Menshikov Palace, designed by Francesco Fontana (an Italian architect) according to the traditions of the Petrine Baroque style. This three-story mansion was the residence of Prince Menshikov –a close friend of Peter the Great and first governor of Saint Petersburg. Since Tsar Peter did not have his own official residence, he often used the Menshikov Palace (especially the Assembly Hall) to celebrate royal weddings (the wedding of his son Prince Aleksey and the wedding of his niece Princess Anna, the future Russian Empress Anna Ioanovna) and meet with foreign ambassadors. Above all, Peter the Great used this palace to persistently promote European culture during parties called “assembles.” Since 1718, under Tsar Peter’s order, assemblies were obligatory for nobility, including noble women for whom assemblies became first opportunities to leave their homes and attend social gatherings. At assemblies, participants demonstrated their skills in European manners, dancing, music, and the art of conversation. Here is a description of a ceremonial dance at an assembly: “Along the entire length of the ballroom, to the sound of the most melancholy music, ladies and gentlemen stood in two rows facing each other; the gentlemen bowed low; the ladies curtsied even lower, first to the front, then to the right, then to the left, to the front again, to the right again and so on.” [3]

Now I am going to the Basil Island to visit the first stone building of Saint Petersburg, the Menshikov Palace, designed by Francesco Fontana (an Italian architect) according to the traditions of the Petrine Baroque style. This three-story mansion was the residence of Prince Menshikov –a close friend of Peter the Great and first governor of Saint Petersburg. Since Tsar Peter did not have his own official residence, he often used the Menshikov Palace (especially the Assembly Hall) to celebrate royal weddings (the wedding of his son Prince Aleksey and the wedding of his niece Princess Anna, the future Russian Empress Anna Ioanovna) and meet with foreign ambassadors. Above all, Peter the Great used this palace to persistently promote European culture during parties called “assembles.” Since 1718, under Tsar Peter’s order, assemblies were obligatory for nobility, including noble women for whom assemblies became first opportunities to leave their homes and attend social gatherings. At assemblies, participants demonstrated their skills in European manners, dancing, music, and the art of conversation. Here is a description of a ceremonial dance at an assembly: “Along the entire length of the ballroom, to the sound of the most melancholy music, ladies and gentlemen stood in two rows facing each other; the gentlemen bowed low; the ladies curtsied even lower, first to the front, then to the right, then to the left, to the front again, to the right again and so on.” [3]

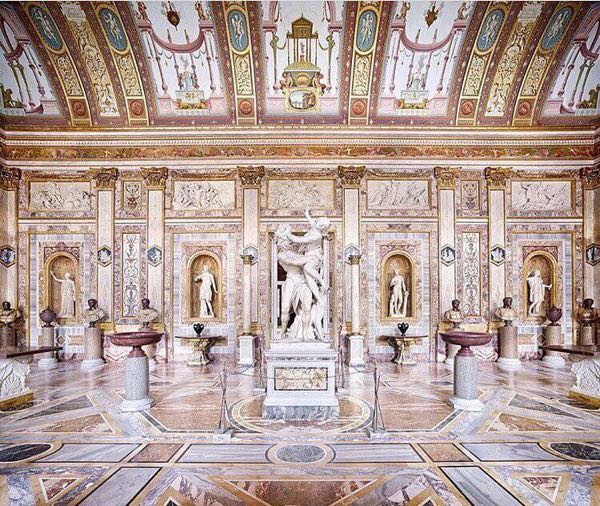

This palace, decorated with tapestries, Chinese lacquer cabinets, and marble sculptures, was also one of the richest in Europe in the 18th century. It took me about two hours to see its numerous rooms.

In my opinion, the most fascinating are four rooms whose walls and ceilings are completely decorated with Dutch porcelain tile (about 28,000 pieces). These rooms are unique and can be seen only in the Menshikov Palace. Dutch porcelain tile was very expensive: even in Holland, where it has been produced, this tile was used to decorate only panels. Yet in the Menshikov Palace there are even several stoves decorated with Dutch tile. Peter the Great was very pleased with the luxury of the Menshikov Palace because he considered this building and its interiors to be a proof that new Russia was in no way inferior to any European country.

In my opinion, the most fascinating are four rooms whose walls and ceilings are completely decorated with Dutch porcelain tile (about 28,000 pieces). These rooms are unique and can be seen only in the Menshikov Palace. Dutch porcelain tile was very expensive: even in Holland, where it has been produced, this tile was used to decorate only panels. Yet in the Menshikov Palace there are even several stoves decorated with Dutch tile. Peter the Great was very pleased with the luxury of the Menshikov Palace because he considered this building and its interiors to be a proof that new Russia was in no way inferior to any European country.

As many monarchs of the 18th century, Peter the Great was interested in curious objects and collected them. In 1718, he ordered that if anybody finds unusual stones or bones, old inscriptions on stones, and other ancient and extraordinary items, this person had to take findings to the city’s commandant. To keep these exhibits, Tsar Peter founded the first museum of natural history and culture, Kunstkamera (German “art chamber”). There is a legend about how Peter the Great had chosen the location for the future museum: he noticed an unusually growing tree and decided to build on this place a museum of curious objects. The building is the oldest edifice in the world constructed especially to house a museum collection: designed according to the Petrine Baroque style, it has in the middle the tower decorated with a sphere. To attract people to the museum, Tsar Peter ordered to give every visitor a glass of wine and a free cup of coffee (a new and exotic drink in Russia in the 18th century). At those times, the museum has been one of the best in Europe, with free entrance for everybody. Today the museum is one of the most interesting in Saint Petersburg: tourists can see not only Tsar Peter’s collection, but other unique objects, for instance, the collection of artifacts brought by Miklouho-Maclay, Russian explorer, from New Guinea.

Tsar Peter has dedicated his life to transforming old Russia and opening new horizons for Russian people. In his letter to Anne, Queen of England, he wrote: “I do not labor to wring out Russia from Russia, but to strengthen and uplift it in itself.” [4] Alexander Pushkin, the great Russian poet, wrote about Tsar Peter’s vision:

Here a great city will be wrought…

Here, by the new for them sea-paths,

Ships of all flags will come to us –

And on all seas our great feast opens.[5]

I hope that my today’s historical journey will help visitors to learn more about the early history and first buildings of Saint Petersburg – “the window to Europe.”

[1] Serov V. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Idiomatic Words and Expressions. Letter “O.” (translation by Tatiana Claudy)

[2] Dostoyevsky, F.M. Notes from the Underground. Part I, chapter II. Project Gutenberg.

[3] Pushkin A. S. The Negro of Peter the Great.

[4] Miller O. F. On Attitudes of Russian Literature to Peter the Great. (Russian Edition). (translation by Tatiana Claudy)

[5]Pushkin A. S. The Bronze Horseman. Poetry Lovers Page

If You Go:

Visas for Russia – Most foreigners need visas to visit Russia.)

The Cabin of Peter the Great (Petrovskaya Embankment, 6. Metro station — Gorkovskaya. Adult ticket $4)

The Summer Palace of Peter the Great – (The palace is currently closed for reconstruction.)

Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (the Kunstkamera) (Universitetskaya Embankment, 3. Adult ticket $6)

The Menshikov Palace (Universitetskaya Embankment, 15. Adult ticket $6)

About the author:

Tatiana Claudy is originally from St. Petersburg, Russia, but she lives with her family in the USA. Her passions include literature, art, music, languages, and photography. During her travels she loves to explore historical sites and take literary journeys. She is a freelance writer and an aspiring mystery writer.

All photos by Tatiana Claudy

- The Kunstkamera

- The Cabin of Peter the Great

- The Study of Peter the Great in the Cabin

- The Summer Palace of Peter the Great

- The Menshikov Palace

- The Sea Study

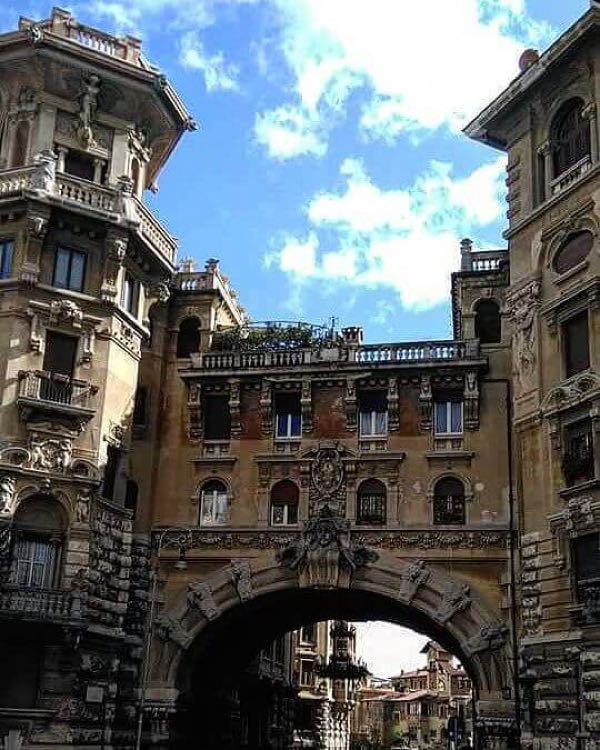

The real heart of the city is the bustling Piazza della Sala, which dates from the 12th century. The characteristic well, “Il Pozzo del Leoncino” (Well of the Little Lion), makes an impressive centre piece to this charming square, which hosts a daily fruit and vegetable market and is surrounded by tiny shops brimming with Tuscan delicacies such as cheese, fresh pasta, delicious bread and a variety of meat products. Lining the square are numerous bars and restaurants, which form the hub of the “movida Pistoiese” and attract hundreds of people of all ages in the evenings, particularly in summer.

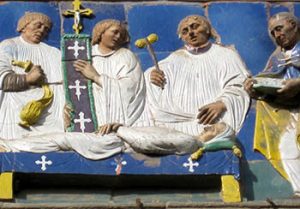

The real heart of the city is the bustling Piazza della Sala, which dates from the 12th century. The characteristic well, “Il Pozzo del Leoncino” (Well of the Little Lion), makes an impressive centre piece to this charming square, which hosts a daily fruit and vegetable market and is surrounded by tiny shops brimming with Tuscan delicacies such as cheese, fresh pasta, delicious bread and a variety of meat products. Lining the square are numerous bars and restaurants, which form the hub of the “movida Pistoiese” and attract hundreds of people of all ages in the evenings, particularly in summer. Apart from typical Tuscan attractions including splendid striped churches, ancient city walls and the fortress of Santa Barbara, built by the Florentines in 1331, Pistoia also has some more unusual monuments. The ancient hospital, dating form the 13th century, features an unmissable glazed ceramic frieze created by various artists, including Giovanni Della Robbia, which depicts the seven works of mercy. Underneath the hospital itself, you can follow a fascinating itinerary where you can see artefacts used by plague victims, an ancient laundry and olive oil mill and finally end up in the smallest anatomical theatre in the world.

Apart from typical Tuscan attractions including splendid striped churches, ancient city walls and the fortress of Santa Barbara, built by the Florentines in 1331, Pistoia also has some more unusual monuments. The ancient hospital, dating form the 13th century, features an unmissable glazed ceramic frieze created by various artists, including Giovanni Della Robbia, which depicts the seven works of mercy. Underneath the hospital itself, you can follow a fascinating itinerary where you can see artefacts used by plague victims, an ancient laundry and olive oil mill and finally end up in the smallest anatomical theatre in the world. Pistoia really comes to life in the summer and hosts The Pistoia Blues Festival in July, where artists such as B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Bob Dylan, Lou Reed and David Bowie have played. The 25th July is the feast of the town’s patron St James, and the streets fill up with a medieval procession displaying stunning costumes, flag waving and music, which culminates in a jousting tournament in Piazza del’ Duomo.

Pistoia really comes to life in the summer and hosts The Pistoia Blues Festival in July, where artists such as B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Bob Dylan, Lou Reed and David Bowie have played. The 25th July is the feast of the town’s patron St James, and the streets fill up with a medieval procession displaying stunning costumes, flag waving and music, which culminates in a jousting tournament in Piazza del’ Duomo.