by Wynne Crombie

After exploring the delights of the Rynek Glowny (Krakow’s Main Market Square) my husband Kent and I set out to discover Krakow’s old Jewish Quarter…Kazimerz. It’s few minutes by tram (#7, #13, #24) or, a very leisurely twenty- minute walk.

At its inception, Kazimierz, founded in the 14th century by King Casimir the Great, was a separate town from Krakow. It was once Krakow’s “medieval twin”. Until the outbreak of World War II, the Jewish religion and culture thrived here. It was the safe haven for Jews from every corner of Europe until the 20th century. It was also a major center of Diaspora (an area outside Palestine settled by the Jews). Then, with the onset of World War II, it became the scene of Nazi devastation. However, there are still significant reminders, of a substantial Jewish community that once existed from 1500 to 1940’s …the forgotten grandeur and landmarks of Kazimierz,

In March 1941, the Germans forced all Krakow Jews to resettle in the newly created ghetto of Kazimierz. The Nazis liquidated it only two years later on March 13, 1943. Most of the 17,000 inhabitants perished in the Nazi concentration camps. Today Krakow has only about 200 Jewish residents.

In March 1941, the Germans forced all Krakow Jews to resettle in the newly created ghetto of Kazimierz. The Nazis liquidated it only two years later on March 13, 1943. Most of the 17,000 inhabitants perished in the Nazi concentration camps. Today Krakow has only about 200 Jewish residents.

Kent and I found that Kazimierz is best discovered on foot. There were so many times we wanted to just stop and reflect on the history before us. As we strolled along Ulica (street) Szeroka we noticed that the signs in Polish were slowly morphing into Hebrew.

Ulica Szeroka runs north and south and has parking available all along the middle of the street. It is not what you would call glamorous; in fact it is a little run-down. It was a nice place to go for a walk as we found out, or just sit and take in the atmosphere

Kazimirez is not beautiful; many of its buildings are run down. A few night clubs have emerged around the Square. We enjoyed just sitting and people watching… modern day residents and a few Jews dressed in shawls and yarmulkes. And, of course, the foreign tourists.

Kazimirez is not beautiful; many of its buildings are run down. A few night clubs have emerged around the Square. We enjoyed just sitting and people watching… modern day residents and a few Jews dressed in shawls and yarmulkes. And, of course, the foreign tourists.

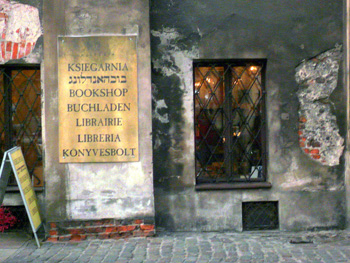

At the top of the Square (Szeroka 2) is the original Jarden Bookshop, going back to pre- World War II. It also doubles as a tourist information source. The Bookshop also runs tours of the area.

At Szeroka Street 40, we entered the Remuh Cemetery. A few worshipers were praying or cleaning grave sites. The cemetery had been widely used from 1551 to 1800. It has hundreds of old tombstones, dating mostly from the Renaissance…still readable.

The synagogues that still stand are not in the best of condition and the actual Jewish quarter lacks the pre-World War II Jewish atmosphere. Almost all have left the area.

The next thing on our list, however, was to sample some of the local food. There was no shortage of Jewish themed restaurants and shops.

The next thing on our list, however, was to sample some of the local food. There was no shortage of Jewish themed restaurants and shops.

We opted for the Kazimierz Market Square or Plac Nowny. It was appealing because it was made up of mostly local working folks walking over for lunch or on a snack break. Never mind that comprehending both Hebrew or Polish were out of our league! At one of the stalls we nibbled on zapiekanki. This is a fantastic toasted baguette with cheese, ketchup and other toppings.

After a little nibbling, shopping and people watching, it was time to explore more of Kazimiretz’s history.

Many synagogues that did survive the war were badly damaged. We visited the Isaak Synogogue built in the 17th century on Kula Street. This is one that had been badly damaged during the War and is still in a restoration process. The historical documents on display are, tremendously interesting. Not just the writing, but the paper and inks used as well.

Another interesting feature are the walls in the prayer hall. Prayers have been painted on the walls for worshipers who couldn’t afford prayer books. Most readings have even been translated into English. A plaque outside states the synagogue was constructed in 1638, so there is some serious history attached to this place of worship.

Another interesting feature are the walls in the prayer hall. Prayers have been painted on the walls for worshipers who couldn’t afford prayer books. Most readings have even been translated into English. A plaque outside states the synagogue was constructed in 1638, so there is some serious history attached to this place of worship.

At Ulica Szeroka 24, the Old Synagogue is the oldest surviving Jewish building in Poland. We found incredibly interesting displays on Jewish life in the Main Prayer Hall (with English translations.) They also play a short film taken before World War II showing everyday street scenes in happier times. When we stepped outside, we realized the film was shot right there, but now there are very few Jews, just their names on buildings and streets.

In addition to the Jewish element, Christianity also had a role in Kazimirez. The Church of Corpus Christi has an awesome historical interior. There are stalls going back to 1629, the altarpiece of 1634, and the ornate mid-18th-century pulpit.

In addition to the Jewish element, Christianity also had a role in Kazimirez. The Church of Corpus Christi has an awesome historical interior. There are stalls going back to 1629, the altarpiece of 1634, and the ornate mid-18th-century pulpit.

Since the late 1980s the area’s Jewish heritage has come back to life, the progress aided by the success of the Spielberg film, Schindler’s List. The restored synagogues cafes, bars, and restaurants are restoring life back into the Jewish Quarter.

Spielberg needed an authentic Jewish quarter for the scenes depicting the Jewish ghetto of Podgorze in Krakow. He chose Kazimierz because this area had not changed since the 1940s,

The entire Kazimierz district is on the UNESCO World Heritage List as an historical monument.

If You Go:

Schindler’s factory:

Wander through Kazimierz, then across the Vistula River Bridge to Podgórze to see more of the Nazi Kraków Ghetto and, a factory of Oscar Schindler. The latter saved nearly 1,200 Jews from the camps. Many of the surviving remnants of the World War II ghetto still exist here.

Walking Directions to Kazimierz from Wawel Castle (Krakow):

Stradom Street leads straight from the Castle’s base to Krakowska Street, and the central thoroughfare of the Kazimierz district.

Krakow Old Town, Jewish Quarter Walking Tour and Optional Wawel Castle Visit

About the author:

Wynne Crombie has a master’s degree in adult education. Her work has appeared in: TravelthruHistory, Travel and Leisure, Dallas Morning News, Senior Living, Cat Fancy, Quilt Magazine, Catholic Digest, Boys ‘Life, Italy Magazine, Irish-American Post.

All photos by Wynne Crombie.

Those simple early ninots have evolved into magnificent wax and polystrene figurines that require such precise skills that the artists who create them now have their own guild, The Guild of Falleros Artists; at least two schools who specialize in training them; two museums dedicated to their work and a part of Valencia known as Cuidad del Artisto Fallera (the City of Falleros Artists) where many of them have full-time workshops.

Those simple early ninots have evolved into magnificent wax and polystrene figurines that require such precise skills that the artists who create them now have their own guild, The Guild of Falleros Artists; at least two schools who specialize in training them; two museums dedicated to their work and a part of Valencia known as Cuidad del Artisto Fallera (the City of Falleros Artists) where many of them have full-time workshops.

The scale model and the massive pieces of the scene in the workshop did not do justice to the full scale of the monument as it was being constructed. Because of its sheer size, much of the actual carpentry happened in the plaza where the public could watch its daily progress. The monument, called Fallas of the World, consisted of a tall wooden human figure surrounded by world “monuments” that had been part of previous years’ fallas structures – the EIffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, the Concorde jet, the statues of David and Moses.

The scale model and the massive pieces of the scene in the workshop did not do justice to the full scale of the monument as it was being constructed. Because of its sheer size, much of the actual carpentry happened in the plaza where the public could watch its daily progress. The monument, called Fallas of the World, consisted of a tall wooden human figure surrounded by world “monuments” that had been part of previous years’ fallas structures – the EIffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, the Concorde jet, the statues of David and Moses.

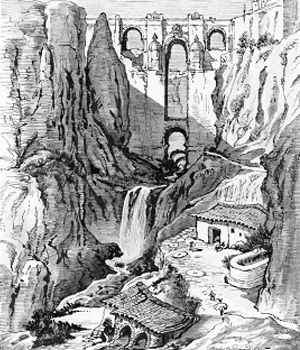

The sun is just setting behind the Serranía de Ronda (Ronda Mountain Range) and an hour and a half later, we arrive, relieved and unscathed.

The sun is just setting behind the Serranía de Ronda (Ronda Mountain Range) and an hour and a half later, we arrive, relieved and unscathed. Ronda is one of the oldest cities in Spain first settled by the Celts around the 10th century BCE as Arunda. The town continued to thrive under the Romans as did the nearby settlement of Acinipo originally founded by the Phoenicians. Today, ruins of a vast Roman theatre and thermal baths dated to the 1st century can be visited about 12 miles northwest from Ronda in the ancient city of Acinipo or, as it is locally known, Ronda La Vieja (Old Ronda.)

Ronda is one of the oldest cities in Spain first settled by the Celts around the 10th century BCE as Arunda. The town continued to thrive under the Romans as did the nearby settlement of Acinipo originally founded by the Phoenicians. Today, ruins of a vast Roman theatre and thermal baths dated to the 1st century can be visited about 12 miles northwest from Ronda in the ancient city of Acinipo or, as it is locally known, Ronda La Vieja (Old Ronda.)

Ronda is the birthplace of the highly gifted 9th century Muslim Andalusí physician, mathematician, and engineer known as Abbas ibn Firnas. Of Berber descent, Firnas was also an illustrious inventor creating such ingenious devices as a water clock, a mechanized planetarium, an armillary sphere, and even a flying machine (for this reason, he is known as the “father of aviation.”) Firnas was also skilled in astronomy, music, and poetry as well as being responsible for introducing glass-making techniques to al-Andalus (Andalusia during Muslim Spain.) Today, he has an airport in northern Baghdad and a lunar crater named in his honour as well as a bridge in Córdoba where he died in 887.

Ronda is the birthplace of the highly gifted 9th century Muslim Andalusí physician, mathematician, and engineer known as Abbas ibn Firnas. Of Berber descent, Firnas was also an illustrious inventor creating such ingenious devices as a water clock, a mechanized planetarium, an armillary sphere, and even a flying machine (for this reason, he is known as the “father of aviation.”) Firnas was also skilled in astronomy, music, and poetry as well as being responsible for introducing glass-making techniques to al-Andalus (Andalusia during Muslim Spain.) Today, he has an airport in northern Baghdad and a lunar crater named in his honour as well as a bridge in Córdoba where he died in 887. The town of Ronda is connected by three bridges that cross the deep canyon adding to the city’s remarkable features. The Roman Bridge is the oldest dating to the 11th century. Although it is Arabic in origin, it was likely constructed over an older Roman bridge. After the Christian conquest it was renamed Puente de San Miguel (St. Michaels Bridge.) Not far away is the early 17th century Puente Viejo (Old Bridge) and smallest of the three. As it was built over the ruins of an old Arab bridge, it is also known as Puente Árabe.

The town of Ronda is connected by three bridges that cross the deep canyon adding to the city’s remarkable features. The Roman Bridge is the oldest dating to the 11th century. Although it is Arabic in origin, it was likely constructed over an older Roman bridge. After the Christian conquest it was renamed Puente de San Miguel (St. Michaels Bridge.) Not far away is the early 17th century Puente Viejo (Old Bridge) and smallest of the three. As it was built over the ruins of an old Arab bridge, it is also known as Puente Árabe. After crossing this bridge, I wander the charming old Moorish quarter with its winding pedestrian streets, white-washed houses, and historic squares. Locally known as La Ciudad (The City), the old quarter is situated on the south side of the gorge as opposed to the newer city on the north. Not for from Puente Nuevo in the historic quarter is an interesting gate known as Arco de Felipe V (Arch of Philip V.) This emblematic arch or gate, crowned by three pinnacles, was reconstructed in 1742 from the old Arab gate that provided access to the medina by the southwest.

After crossing this bridge, I wander the charming old Moorish quarter with its winding pedestrian streets, white-washed houses, and historic squares. Locally known as La Ciudad (The City), the old quarter is situated on the south side of the gorge as opposed to the newer city on the north. Not for from Puente Nuevo in the historic quarter is an interesting gate known as Arco de Felipe V (Arch of Philip V.) This emblematic arch or gate, crowned by three pinnacles, was reconstructed in 1742 from the old Arab gate that provided access to the medina by the southwest.

Next I decide to visit the 14th century Alminar (minaret) of San Sebastián in the old Moorish quarter. The impressive square tower is all that remains of a mosque that once stood here before it was destroyed and rebuilt by the Christians. The lower part is clearly Moorish in architecture while the top part was added by the Christians to house the bell tower of the San Sebastián Church that also once stood here.

Next I decide to visit the 14th century Alminar (minaret) of San Sebastián in the old Moorish quarter. The impressive square tower is all that remains of a mosque that once stood here before it was destroyed and rebuilt by the Christians. The lower part is clearly Moorish in architecture while the top part was added by the Christians to house the bell tower of the San Sebastián Church that also once stood here. Near the minaret is the early 14th century Casa de Mondagrón that is also well worth visiting. The stone palace, promoted as “probably the most important civil monument in Ronda”, was the former residence of a king and its last Muslim governor. In 1485, Ronda was captured by the Christians and a few years later, King Fernando and Queen Isabella also made this palace their home. Although restored and enlarged during the 18th century, the exterior pales in comparison to the beauty of its interior adorned with arched patios, ceramic tiles, marble columns, balconies overlooking at inner courtyards, decorated fountains and water gardens. Today it also houses an auditorium and a municipal museum on the second floor.

Near the minaret is the early 14th century Casa de Mondagrón that is also well worth visiting. The stone palace, promoted as “probably the most important civil monument in Ronda”, was the former residence of a king and its last Muslim governor. In 1485, Ronda was captured by the Christians and a few years later, King Fernando and Queen Isabella also made this palace their home. Although restored and enlarged during the 18th century, the exterior pales in comparison to the beauty of its interior adorned with arched patios, ceramic tiles, marble columns, balconies overlooking at inner courtyards, decorated fountains and water gardens. Today it also houses an auditorium and a municipal museum on the second floor. Ronda is also the birthplace of bullfighting. Not only was the first professional bullfighter born here in 1754 but it is also home of the oldest and largest bullfighting ring in the country dated to 1785. Another unique and unusual aspect of Ronda is their fascination with bandoleros (bandits); particularly those between the 18th and 19th centuries.

Ronda is also the birthplace of bullfighting. Not only was the first professional bullfighter born here in 1754 but it is also home of the oldest and largest bullfighting ring in the country dated to 1785. Another unique and unusual aspect of Ronda is their fascination with bandoleros (bandits); particularly those between the 18th and 19th centuries.

The origins of the city can be traced all the way to the Romans. The Roman Emperor Diocletian, who lived in the 4th century AD, wanted to build himself a retirement mansion. He liked the area of today’s Split for its natural beauties and the warm Adriatic Sea, so he had it built there. In the centuries that followed, the city of Split grew around it, even after the Romans were long gone. The Palace and its surroundings eventually become the historical city core of Split (or Split Old Town), and nowadays the remains of the Diocletian’s Palace are among the best preserved remains of a Roman palace in the world. It was included in the register of the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage in 1979, and is even featured on Croatian banknotes. Built in an irregular rectangle, it was a combination of a luxurious villa and a military camp. Its walls and the center court, the Peristyle, now housing various vendors and souvenir shops, can be explored freely by tourists. However, a tour through its cellar includes a 5 Euro entrance fee.

The origins of the city can be traced all the way to the Romans. The Roman Emperor Diocletian, who lived in the 4th century AD, wanted to build himself a retirement mansion. He liked the area of today’s Split for its natural beauties and the warm Adriatic Sea, so he had it built there. In the centuries that followed, the city of Split grew around it, even after the Romans were long gone. The Palace and its surroundings eventually become the historical city core of Split (or Split Old Town), and nowadays the remains of the Diocletian’s Palace are among the best preserved remains of a Roman palace in the world. It was included in the register of the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage in 1979, and is even featured on Croatian banknotes. Built in an irregular rectangle, it was a combination of a luxurious villa and a military camp. Its walls and the center court, the Peristyle, now housing various vendors and souvenir shops, can be explored freely by tourists. However, a tour through its cellar includes a 5 Euro entrance fee. A city of such interesting history has several museums and galleries in which parts of that history are exhibited. For instance, the Gallery of Fine Arts contains works spanning through six centuries, thus providing an overview of artistic movements in Split and Croatia. Founded in 1931, it houses one of the greatest exhibitions of paintings and sculpture by major Croatian artists, but dedicating space to contemporary art as well.

A city of such interesting history has several museums and galleries in which parts of that history are exhibited. For instance, the Gallery of Fine Arts contains works spanning through six centuries, thus providing an overview of artistic movements in Split and Croatia. Founded in 1931, it houses one of the greatest exhibitions of paintings and sculpture by major Croatian artists, but dedicating space to contemporary art as well.

The cuisine of Split and the surrounding area is heavily based on seafood; fish, clams, oysters are usually boiled or grilled and served with vegetables or potato. Local delicacies include grilled sardines, the octopus salad, or the special kind of dry ham called “prsut”. Served with local wine, the food is usually not spicy, but some restaurants, drawing influences from other Mediterranean countries, started adding exotic spices to traditional Dalmatian dishes, giving them a new spin. For classic local delicacies search for a “konoba” sign, denoting a family-owned tavern specialized in authentic dishes. Of course, if you’re not a lover of seafood, there are plenty of fast food joints in every part of the city.

The cuisine of Split and the surrounding area is heavily based on seafood; fish, clams, oysters are usually boiled or grilled and served with vegetables or potato. Local delicacies include grilled sardines, the octopus salad, or the special kind of dry ham called “prsut”. Served with local wine, the food is usually not spicy, but some restaurants, drawing influences from other Mediterranean countries, started adding exotic spices to traditional Dalmatian dishes, giving them a new spin. For classic local delicacies search for a “konoba” sign, denoting a family-owned tavern specialized in authentic dishes. Of course, if you’re not a lover of seafood, there are plenty of fast food joints in every part of the city. During the summer tourist season the local nightlife flourishes, especially along the Bacvice beachside, featuring several late-opening clubs and beach bars. But the city is big and diverse enough for anyone, with different clubs playing vastly different music. Electronic music lovers should proceed to the minimally decorated Quasimodo, Split’s top venue for DJ nights, or the Jungla (Hula Hula), playing house and techno music. Rock lovers should visit the Kocka or Judino Drvo, where local bands often perform. O’ Hara Music Club is popular among tourists, due to its attractive location at the Zenta waterfront; hosting great parties, it’s great for dancing and drinking. Also, a plethora of bars can be found at the main city promenade, locally known as Riva, which is a great place for slow walks among the rows of palm trees with the incredible view of turquoise Adriatic Sea.

During the summer tourist season the local nightlife flourishes, especially along the Bacvice beachside, featuring several late-opening clubs and beach bars. But the city is big and diverse enough for anyone, with different clubs playing vastly different music. Electronic music lovers should proceed to the minimally decorated Quasimodo, Split’s top venue for DJ nights, or the Jungla (Hula Hula), playing house and techno music. Rock lovers should visit the Kocka or Judino Drvo, where local bands often perform. O’ Hara Music Club is popular among tourists, due to its attractive location at the Zenta waterfront; hosting great parties, it’s great for dancing and drinking. Also, a plethora of bars can be found at the main city promenade, locally known as Riva, which is a great place for slow walks among the rows of palm trees with the incredible view of turquoise Adriatic Sea.

The Palace is also the location of the annual Festival of Flowers (usually held in May), where exhibitors display their flower arrangements based on a particular theme. Visually stunning, it’s a must-visit if you’re in the city at that time. If you’re interested in Roman culture, you’ll be happy to hear that there’s a whole festival dedicated to it. The Days of Diocletian are usually held in late August, and the entire area of the Palace becomes a living monument to the Romans, featuring their cuisine, lifestyle, clothing and customs. Entertaining and educational at the same time, the Days of Diocletian are especially popular with kids.

The Palace is also the location of the annual Festival of Flowers (usually held in May), where exhibitors display their flower arrangements based on a particular theme. Visually stunning, it’s a must-visit if you’re in the city at that time. If you’re interested in Roman culture, you’ll be happy to hear that there’s a whole festival dedicated to it. The Days of Diocletian are usually held in late August, and the entire area of the Palace becomes a living monument to the Romans, featuring their cuisine, lifestyle, clothing and customs. Entertaining and educational at the same time, the Days of Diocletian are especially popular with kids.

At this point, I wasn’t worried about the other passengers’ thoughts. Dignity, respect, pretending not to be a tourist – all out the window having tried very unsuccessfully to validate my 5 Euro ticket for a solid ten minutes of the bus ride. I could stare and gawp all I wanted; and so I did, drinking in that immense sight. I had read the myths since I was a kid, studied the history in school, and poured over the art for project after project in undergrad. Thrill raced through me faster than the cold had, as I discovered for the first time something I thought I already knew. Here it all was in 3D.

At this point, I wasn’t worried about the other passengers’ thoughts. Dignity, respect, pretending not to be a tourist – all out the window having tried very unsuccessfully to validate my 5 Euro ticket for a solid ten minutes of the bus ride. I could stare and gawp all I wanted; and so I did, drinking in that immense sight. I had read the myths since I was a kid, studied the history in school, and poured over the art for project after project in undergrad. Thrill raced through me faster than the cold had, as I discovered for the first time something I thought I already knew. Here it all was in 3D.

Thankfully, what he actually meant was that he couldn’t get me to the front door along the one-way pedestrian street. But he could get me close and, after a nice little chat about whether it was more expensive to live in the UK, he did. In hindsight, it was quite beneficial to have a little tour of the city. But on a pitch black evening in February, hindsight wasn’t on my mind. What I was actually thinking about was snow – snow in the Mediterranean. For the first time in five years, it was forecast to snow in Athens and as we drove, big white flakes melted on the windscreen. Not enough to stick in town, but there was plenty to pile up in the higher altitudes. From the Acropolis and the top of Lycabettus Hill, I spun circles the next day, looking round at the mountains that ringed the basin where the city lived. The big, slow flakes from last night had left them white-capped under cracks of blue sky between stacked layers of grey and white cloud. The sun, when it did decide to join the day, was cold and sharp and my ears froze. I had forgotten to pack a hat.

Thankfully, what he actually meant was that he couldn’t get me to the front door along the one-way pedestrian street. But he could get me close and, after a nice little chat about whether it was more expensive to live in the UK, he did. In hindsight, it was quite beneficial to have a little tour of the city. But on a pitch black evening in February, hindsight wasn’t on my mind. What I was actually thinking about was snow – snow in the Mediterranean. For the first time in five years, it was forecast to snow in Athens and as we drove, big white flakes melted on the windscreen. Not enough to stick in town, but there was plenty to pile up in the higher altitudes. From the Acropolis and the top of Lycabettus Hill, I spun circles the next day, looking round at the mountains that ringed the basin where the city lived. The big, slow flakes from last night had left them white-capped under cracks of blue sky between stacked layers of grey and white cloud. The sun, when it did decide to join the day, was cold and sharp and my ears froze. I had forgotten to pack a hat. I found the lower gardens on the hill around the Acropolis full of temples and remains of buildings, statues, column capitals, and broken bits of foundations. The museums and Acropolis grounds felt more like walking into the pictures from the books I had read, studied, photocopied, and researched for the past six years. With an almost reverence, my eyes traced the draping folds of the stone garments that were so much softer and more alive than the drawings and photographs had shown me. Poseidon and Athena had to come to life and watched me carefully as I revelled in the neatly arranged Corinthian column caps I had modelled my own exhibition project on.

I found the lower gardens on the hill around the Acropolis full of temples and remains of buildings, statues, column capitals, and broken bits of foundations. The museums and Acropolis grounds felt more like walking into the pictures from the books I had read, studied, photocopied, and researched for the past six years. With an almost reverence, my eyes traced the draping folds of the stone garments that were so much softer and more alive than the drawings and photographs had shown me. Poseidon and Athena had to come to life and watched me carefully as I revelled in the neatly arranged Corinthian column caps I had modelled my own exhibition project on. After that, I walked and walked and walked the streets, looking for more awe-inspiring moments whatever the weather. Psirri turned out to be a fascinating district. I had booked myself into a lovely little hostel called City Circus for the week, where thankfully everything was warm and cozy with bountiful breakfast and friendly staff. Around the corner was a little spiders’ web of streets and five-point star intersections filled with shops and food. There were bars and music and fried filo dough and cheese concoctions in any shape I fancied. Lamp light and candle light poured through colored glass in the windows to join the colorful plaster walls. The music burst from inside the restaurants and the stones smacked hard under my new shoes. I didn’t want to stay long. I just wanted to see all of it, drink in this new, vivacious, loud place that breathed under my feet.

After that, I walked and walked and walked the streets, looking for more awe-inspiring moments whatever the weather. Psirri turned out to be a fascinating district. I had booked myself into a lovely little hostel called City Circus for the week, where thankfully everything was warm and cozy with bountiful breakfast and friendly staff. Around the corner was a little spiders’ web of streets and five-point star intersections filled with shops and food. There were bars and music and fried filo dough and cheese concoctions in any shape I fancied. Lamp light and candle light poured through colored glass in the windows to join the colorful plaster walls. The music burst from inside the restaurants and the stones smacked hard under my new shoes. I didn’t want to stay long. I just wanted to see all of it, drink in this new, vivacious, loud place that breathed under my feet. Athens’ graffiti was most unexpected. It was everywhere, unabashedly adorning abandoned houses, old government buildings, and ramshackle metal fences. My walk into town was a burst of color, screaming ideas at me that I could not understand. But still I knew they were trying to say something, trying to be heard amidst the throng of twelve-story concrete apartment complexes and canvas canopies. After a brisk souvenir search through the bustling side streets around Monastirkai Square, I grabbed a latte in a fourth-story coffee bar. It had huge windows looking out over the red tile roofs, all uneven height and helter-skelter pitch before stopping abruptly for the Hill to rise behind them. Buzzing with voices, the room was warm and curls of smoke caressed the windows. Out of the the top of the hill, the Acropolis rose overlooking the city, ever listening as the centuries marched past under its watchful gaze. How many stories had it seen unfold? What tales could it tell if only I could ask – what stories not found in any of my books? I would never know. My own stories would have to be enough for my curiosity.

Athens’ graffiti was most unexpected. It was everywhere, unabashedly adorning abandoned houses, old government buildings, and ramshackle metal fences. My walk into town was a burst of color, screaming ideas at me that I could not understand. But still I knew they were trying to say something, trying to be heard amidst the throng of twelve-story concrete apartment complexes and canvas canopies. After a brisk souvenir search through the bustling side streets around Monastirkai Square, I grabbed a latte in a fourth-story coffee bar. It had huge windows looking out over the red tile roofs, all uneven height and helter-skelter pitch before stopping abruptly for the Hill to rise behind them. Buzzing with voices, the room was warm and curls of smoke caressed the windows. Out of the the top of the hill, the Acropolis rose overlooking the city, ever listening as the centuries marched past under its watchful gaze. How many stories had it seen unfold? What tales could it tell if only I could ask – what stories not found in any of my books? I would never know. My own stories would have to be enough for my curiosity.

On the way back, we scootered through a seaside town and grabbed coffee. After the hustle of the city and the very present feeling of history at Aphaia, it was odd how quiet the coasts were. Big, abandoned holiday homes half-built lingered just off the shore, silent concrete skeletons that didn’t tell stories like the ancient ruins. I thought it was only the island, but as I sat in a restaurant on Athen’s shore, I was as the sole customer. It was full of chairs placed upside down on tables – a hundred inside and maybe more than a hundred outside. The place felt expectant but mournful, waiting for the summer visitors to come and fill it with vibrance. As I stared silently down the coast, I felt out of place for the first time on my trip. In walking in the footsteps of the ancient past, I had created my own stories. But each story I created was filled with the stories that had come before me. In walking the recently built-up coastline, I felt disconnected from the past, though it surely had no shortage of stories to tell. Perhaps I’m far too picky about architecture.

On the way back, we scootered through a seaside town and grabbed coffee. After the hustle of the city and the very present feeling of history at Aphaia, it was odd how quiet the coasts were. Big, abandoned holiday homes half-built lingered just off the shore, silent concrete skeletons that didn’t tell stories like the ancient ruins. I thought it was only the island, but as I sat in a restaurant on Athen’s shore, I was as the sole customer. It was full of chairs placed upside down on tables – a hundred inside and maybe more than a hundred outside. The place felt expectant but mournful, waiting for the summer visitors to come and fill it with vibrance. As I stared silently down the coast, I felt out of place for the first time on my trip. In walking in the footsteps of the ancient past, I had created my own stories. But each story I created was filled with the stories that had come before me. In walking the recently built-up coastline, I felt disconnected from the past, though it surely had no shortage of stories to tell. Perhaps I’m far too picky about architecture.