by Larry Zaletel

A people’s culture is defined not only by their traditions and values but also by their food and drink. Food brings people together especially when they gather around the dinner table.

Traveling across the globe, there is a variety of good food from various different nationalities and sampling food of different countries can be very rewarding. Although the food may be prepared differently in Europe, have an open mind and enjoy new flavors and sample the scrumptious delicacies.

Austria

Some of my personal favorite ethnic eats are in Austria. In Wels a small town in the Northwestern section of the country there is a local market which is very similar to the Westside Market in Cleveland, Ohio. A new building was recently constructed to house the vendors. On the outside of the market vendors sell various fresh fruits and vegetables etc. Nothing there is prepackaged. Inside the building the vendors provide various types of fresh food including meat, poultry, eggs, cheese and even schnapps (whiskey). My favorite vendor has barbecue roast chicken on a spit and as of late a new item lightly breaded chicken wings which go well with a stein (a traditional German beer tankard) of beer. Priced by the kilogram (2.2 pounds) US $3.00-$5.00.

Some of my personal favorite ethnic eats are in Austria. In Wels a small town in the Northwestern section of the country there is a local market which is very similar to the Westside Market in Cleveland, Ohio. A new building was recently constructed to house the vendors. On the outside of the market vendors sell various fresh fruits and vegetables etc. Nothing there is prepackaged. Inside the building the vendors provide various types of fresh food including meat, poultry, eggs, cheese and even schnapps (whiskey). My favorite vendor has barbecue roast chicken on a spit and as of late a new item lightly breaded chicken wings which go well with a stein (a traditional German beer tankard) of beer. Priced by the kilogram (2.2 pounds) US $3.00-$5.00.

Not too far from Wels is the small village of Marchtrenk, Austria. On Saturday morning, market day in the square, a white Mercedes truck (long before food trucks became popular in the United States) provides barbeque chicken to the many people lined up waiting to order. The truck is a mobile rotisserie converted to hold two rows of rotisserie chicken gently rotating. Each bank holds five rotisserie spits of chicken. Priced by the kilogram US $5:00.

Croatia

There are other taste treats to learn about and experience. Crossing from Slovenia into Croatia passing through village after village the signs for roast pork (svinjina) and lamb (jagnjetina grilled lamb both roasted on spit) began to appear. The local Gostionas (Restaurants, Bars) were preparing their grills for roasting. As luck would have it, we always seemed to miss many of these establishments. It might have been sheer luck and or just bad timing. We were either too early or too late for lunch or there was not a Gostiona located in the area where we were.

There are other taste treats to learn about and experience. Crossing from Slovenia into Croatia passing through village after village the signs for roast pork (svinjina) and lamb (jagnjetina grilled lamb both roasted on spit) began to appear. The local Gostionas (Restaurants, Bars) were preparing their grills for roasting. As luck would have it, we always seemed to miss many of these establishments. It might have been sheer luck and or just bad timing. We were either too early or too late for lunch or there was not a Gostiona located in the area where we were.

However luck was on our side one morning just a little before noon as we headed toward Zagreb our way to Slovenia. At the outskirts of a small village we came to an intersection in the road. I stopped to determine which direction to proceed as there were no road signs. My wife said, “Look to your left.” I glanced to the left and there on the spit were two suckling pigs roasting to perfection. I looked at my wife and said, “Lunch time.” The A-Frame sign in front of the Gostiona listed Odojak (suckling pig in Croatian).

Finally the timing was right. We sat outside under a covered porch after purchasing a kilogram of roast pork which included salad, bread and beer. Everything was tasty. My wife sampled the pork and I began to enjoy the additional treat of the lightly tanned hard crunchy pork skin that brought back a lot of fond memories. We washed everything down with Ozujsko beer and I believe that the beer in Europe is delicious whether you enjoy it in Austria, Slovenia, Croatia or Germany. It doesn’t matter it all tastes good. They have been brewing beer for 300-400 years and they have got it together US $15:00.

Having been in the former Yugoslavia a few times we learned over the years on what to look for when it comes to roast pork and lamb. Normally vendors and restaurateurs post signs advertising their wares along the road. Driving through Split on the Jadranska Magistrala along the coast toward Dubrovnik about lunch time we just could not find an establishment that had roast lamb or pork. Either we missed the signs or there just weren’t any. Finally we stopped at a local restaurant and we were given directions on where to find janjetina. Down the road and up the side of a sparsely covered mountain, we traveled higher and higher on the narrow pebbled road turning this way and that as the road curved back and forth along the side of the mountain, my cousin sitting in the back seat hanging firmly on to the hand strap fixed to the car roof. We drove on and on for over an hour. Finally we found it. The war had taken its toll. It was a bombed out building and on the side of the building a faded wooden sign advertised jagnjetina. My cousin started laughing hysterically!!! Someone was having a good laugh on us. Consequently we did not have roast pork or jagnjetina this day.

Having been in the former Yugoslavia a few times we learned over the years on what to look for when it comes to roast pork and lamb. Normally vendors and restaurateurs post signs advertising their wares along the road. Driving through Split on the Jadranska Magistrala along the coast toward Dubrovnik about lunch time we just could not find an establishment that had roast lamb or pork. Either we missed the signs or there just weren’t any. Finally we stopped at a local restaurant and we were given directions on where to find janjetina. Down the road and up the side of a sparsely covered mountain, we traveled higher and higher on the narrow pebbled road turning this way and that as the road curved back and forth along the side of the mountain, my cousin sitting in the back seat hanging firmly on to the hand strap fixed to the car roof. We drove on and on for over an hour. Finally we found it. The war had taken its toll. It was a bombed out building and on the side of the building a faded wooden sign advertised jagnjetina. My cousin started laughing hysterically!!! Someone was having a good laugh on us. Consequently we did not have roast pork or jagnjetina this day.

Bosnia & Herzegovina (BIH)

On another occasion we were traveling by bus from Sarajevo to Mostar we stopped in the town of Jablanica to view the local historical sights. We learned from the locals just on the outskirts about one kilometer south of Jablanica was the restaurant Zdrava Voda (Health Water). There on six roasting spits was lamb grilling on an open fire continuously throughout the day enough to quell the hunger for both the tourist traveling between Sarajevo and Mostar and the local population. The price was US $15.00 which included potatoes, salad, and bread. Jablanica is known for this mouth watering delicacy and that there are over 8 restaurants in the vicinity that serve it. www.zdravavoda.co.ba

On another occasion we were traveling by bus from Sarajevo to Mostar we stopped in the town of Jablanica to view the local historical sights. We learned from the locals just on the outskirts about one kilometer south of Jablanica was the restaurant Zdrava Voda (Health Water). There on six roasting spits was lamb grilling on an open fire continuously throughout the day enough to quell the hunger for both the tourist traveling between Sarajevo and Mostar and the local population. The price was US $15.00 which included potatoes, salad, and bread. Jablanica is known for this mouth watering delicacy and that there are over 8 restaurants in the vicinity that serve it. www.zdravavoda.co.ba

We learned from a local butcher in Medjugorje that the Restaurant Udovice located in Sretnice, 88203 Krusevo has Roast Lamb. It is located about 7-10 kilometers from Medjugorje and about 9 kilometers from Mostar. www.udovice.ba. The restaurant has two barbeque pits with seven spits for roasting Janjetina outside in the front of the establishment. Price US $15.00 which included potatoes, salad, and bread.

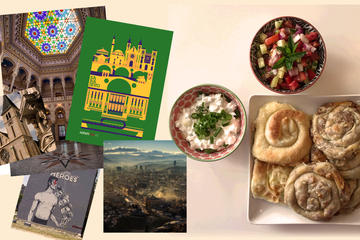

In Sarajevo the restaurant Cevabdzinica Zeljo, on street Kundurdziluk 18, in the Bascarsija seems to be the favorite place for locals to enjoy a “healthy” meal of cevapcici with onions, sour cream and yogurt. Cevapcici is beef minced meat in a roll served with pita bread and priced under US $7.00. Other versions of this delicacy are made with ground lamb, veal, and pork.

In Sarajevo the restaurant Cevabdzinica Zeljo, on street Kundurdziluk 18, in the Bascarsija seems to be the favorite place for locals to enjoy a “healthy” meal of cevapcici with onions, sour cream and yogurt. Cevapcici is beef minced meat in a roll served with pita bread and priced under US $7.00. Other versions of this delicacy are made with ground lamb, veal, and pork.

Pizza is almost as much of a staple in the former Yugoslavia as it is in the United States. I noticed how popular it was when first visiting Slovenia. I was surprised that pizza appeared to be more readily available than local food.

Pizza is not made the same way as in the United States. The crust is somewhat thinner and the toppings and combinations are different although very tasty. Seafood including squid, shrimp is used and also sweet corn. Sausage is very popular and there are many different varieties. Each country has its own types of sausage therefore the assortment of tastes are endless. One of our favorites in Sarajevo was the restaurant café Pizzeria Oscar that provides pizza and spaghetti, price US $15.00-$25.00.

Sarajevo Cultural Walking Tour with Local Food Tasting

If You Go:

How to get there

There are no direct flights from the United States to Austria, Croatia, and Bosnia & Hercegovina. However air travelers can go to Frankfurt, Munich, Paris, or London for connecting airlines. Driving through Croatia from Rijeka toward Dubrovnik and points south is about a 3-4 hour drive. At present the new autobahn completed in 2005 ends at Ravca south of Split. Construction is ongoing and continuation of the highway to southernmost Dalmatia and Dubrovnik is scheduled to be complete sometime in the near future.

Where to stay

A Gostilna (Gasthaus in German) is a modest country inn serving home cooked meals. There is no hard and fast rule but many gostilna’s have sleeping arrangements and usually include breakfast in the morning. If there is a picture of a bed hanging out in front of the establishment then they have sleeping accommodations.

Besides hotels and Gostilna’s there are many bed & breakfast (sobes) that are common in Europe. There are signs along the roadsides advertising them. The local tourist bureaus usually have list of sobes with prices and further information. They are highly recommended as a delightful way to meet the people and make new friends. We have been very fortunate to find some very charming sobes in our travels. We are thus able to meet the people, get acquainted with those from other cultures and learn about them and their way of life.

Usually the price can be negotiated. Prices average about $45-$80 per night and they are much cheaper than hotels and normally include breakfast. We have stayed in sobes in Germany, Austria, Slovenia and Croatia and have revisited them on several occasions.

The Gostilna Pri Belokranjcu, Kandijska cesta 63, 8000 Novo Mesto, Slovenia is situated almost in the center of town across the street from the Renault factory and is close to two shopping malls. This family bed and breakfast has 28 rooms with double beds. The owners Branko and Mojca Vrbetic offers daily menus with home made bread and a local wine called Cvicek. Refrigerators and laundry services for extended guests are available. Slovenian, Serbian/Croatian, Russian, German, Italian and English are spoken. Tel 386 7 30 28 444, Price $60-$80 per night. Very good home cooked food. www.pribelokranjcu-vp.si

Boutique 36, price 67 Euro, . 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia-Hercegovina, Safvet bega Basagica 36, www.hb36.ba

Zagreb Food & Wine Journey: Farmer’s market – Brunch – Boutique winery

Where to eat

Gostilna and Restaurant Ansenik, 4275 Begunje, Slovenia, Telephone 386 4 530 70 30, www.avsenik.com. This is a genteel family establishment that includes very good homemade Slovenian food, international cuisine, venison, fish and other seafood dishes. Additionally they offer both vegetarian and grilled dishes. Prices are moderate. There is a children’s playground, conference area, and dance-floor. There is music on Wednesdays and Fridays evenings in the multi purpose hall which seats 220 persons. Hours: Daily 10:00 AM-11:00 PM, Sunday: 10:00AM-9 PM, Monday: Closed.

Pizzeria & Spaghettarija Don Bobi, Kandijska Cesta 14, 8000 Novo Mesto, Slovenia. Tel 386 7 338 24 00, email don.bobi@siol.net. Extensive menu and moderately priced $8-$18. Complete with indoor and outdoor dining. This is one of our favorites. Very good pasta and pizza.

Gostilna Ancka, Delavska 18, 4208 Sencur, Slovenia is about a five minute ride from the Joze Pucnik Airport. Tel 386 4 251 52 00. They offer homemade Slovenian dishes, venison, freshwater fish, and vegetarian dishes. It is complete with indoor and outdoor dining that includes a huge terrace. It is a very nicely decorated restaurant with a friendly staff with over 35 years of experience. The food is freshly prepared and their style of ribs is very good. Prices are moderate.

Barhana, Dulagina Cikma 8, www.barhana.ba, in the Bascarsija, Sarajevo, Bosnia-Hercegovina. We visited it on a cold drizzly night and its good wholesome food of lamb Goulash and the local drink of Rakija (plum brandy) which took the chill out of our bones. Prices are moderate. 033 447 727.

Konoba Mediterano is located across from the Cathedral, Dubrovnik, Croatia. Types of food include risotto, pasta, seafood, and other Croatian favorites. Prices, moderate plus.

About the author:

Larry is a freelance travel writer, an avid and dedicated traveler, and recurring visitor to Europe, the Caribbean and Hawaii. He writes about the various people that he has met and places that he has visited during my travels. Larry is a regular contributor to Travel Thru History.

All photographs by Larry Zaletel:

Whole Chickens sold from a Truck, Marchtrenk, Austria

Chicken Stand at the market in Marchtrenk, Austria

Chicken Wings Marchtrenk, Austria

Lamb on a Spit, Pag, Croatia

Pizzeria Oscar in Sarajevo, Bosnia

Lamb on a Spit, Jablanica, Bosnia

Mainz history goes back to when the Romans built a fort here around the 1st century BC. The name “Mainz” may have derived from the Roman name for the river, Main. But until the 20th century it was referred to in English as Mayence. Besides this temple there are other ruins nearby including the site of the original Roman citadel where there is a cenotaph raised by legionaries to commemorate their hero Drusus. Among the sites are the ruins of an aqueduct and theatre. Some of the artifacts of Roman times can be viewed in the Museum of Antike Schiffahrt and Mainz most important museum, the Landesmuseum.

Mainz history goes back to when the Romans built a fort here around the 1st century BC. The name “Mainz” may have derived from the Roman name for the river, Main. But until the 20th century it was referred to in English as Mayence. Besides this temple there are other ruins nearby including the site of the original Roman citadel where there is a cenotaph raised by legionaries to commemorate their hero Drusus. Among the sites are the ruins of an aqueduct and theatre. Some of the artifacts of Roman times can be viewed in the Museum of Antike Schiffahrt and Mainz most important museum, the Landesmuseum.

Mainz is home to a Carnival, the Mainzer Fassenacht, originating in the 19th century. We walked around the carnival square where there’s a statue of Friedrich von Schiller, a 19th century writer and poet for whom the Square is named. The Carnival is held on Rosenmontag (Rose Monday), before Ash Wednesday and is one of the city’s biggest celebrations.

Mainz is home to a Carnival, the Mainzer Fassenacht, originating in the 19th century. We walked around the carnival square where there’s a statue of Friedrich von Schiller, a 19th century writer and poet for whom the Square is named. The Carnival is held on Rosenmontag (Rose Monday), before Ash Wednesday and is one of the city’s biggest celebrations. The immense Cathedral of Saint Martin is nearly 1000 years old, built in Romanesque style. It has six individual pipe organs inside all accessed from one large console. The Augustine Church with its magnificent Baroque facade was built originally as a hermit’s monastery in the mid l700’s and is now a seminary church noted for its beautiful interior with ceiling frescoes that provide insights into the life of St Augustine. The Catholic Church of St. Peter is one of the most important Baroque building in the city. Originally a monastery, the present church was built between 1740 and 1756 by architect Johann Valentin Thoman. Inside you’ll see amazing Baroque altars and ceiling frescoes. Christuskirche is an evangelical church in an Italian High Renaissance style. It serves as a music venue as well as church. The old Gothic Church of St. Christoph dates to the 9th century. It contains an original 15th century baptismal font. Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the first printing press was baptized here.

The immense Cathedral of Saint Martin is nearly 1000 years old, built in Romanesque style. It has six individual pipe organs inside all accessed from one large console. The Augustine Church with its magnificent Baroque facade was built originally as a hermit’s monastery in the mid l700’s and is now a seminary church noted for its beautiful interior with ceiling frescoes that provide insights into the life of St Augustine. The Catholic Church of St. Peter is one of the most important Baroque building in the city. Originally a monastery, the present church was built between 1740 and 1756 by architect Johann Valentin Thoman. Inside you’ll see amazing Baroque altars and ceiling frescoes. Christuskirche is an evangelical church in an Italian High Renaissance style. It serves as a music venue as well as church. The old Gothic Church of St. Christoph dates to the 9th century. It contains an original 15th century baptismal font. Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the first printing press was baptized here. There are several interesting day-trips out of Mainz. The region is rich in variety with idyllic river scenery, historical towns and picturesque villages. The Rhineland-Palatinate is famous as a wine region and the romantic castles along the river and was named by UNESCO as one of the most beautiful landscapes and world heritage sites.

There are several interesting day-trips out of Mainz. The region is rich in variety with idyllic river scenery, historical towns and picturesque villages. The Rhineland-Palatinate is famous as a wine region and the romantic castles along the river and was named by UNESCO as one of the most beautiful landscapes and world heritage sites.

We were part of a continuous line of visitors from around the world who did not need a Silence sign. The only noise came from the shuffling of feet. We were on a tour of Poland and had been visiting Krakow. After making the one hour drive from Krakow, we arrived at Auschwitz I. (Auschwitz II or Birkenau, is a mile away). Admission is free.

We were part of a continuous line of visitors from around the world who did not need a Silence sign. The only noise came from the shuffling of feet. We were on a tour of Poland and had been visiting Krakow. After making the one hour drive from Krakow, we arrived at Auschwitz I. (Auschwitz II or Birkenau, is a mile away). Admission is free. During the early days, the Nazis would take pictures of each inmate. These seemingly endless 8 x 10 glass-covered photographs surrounded a long narrow hall. The inmates looked healthy, for they had just arrived. The name was printed below each photo and included the date of arrival and the date of death—sometimes just days apart. When photography became too expensive, the Nazis started tattooing numbers on the inmates’ arms.

During the early days, the Nazis would take pictures of each inmate. These seemingly endless 8 x 10 glass-covered photographs surrounded a long narrow hall. The inmates looked healthy, for they had just arrived. The name was printed below each photo and included the date of arrival and the date of death—sometimes just days apart. When photography became too expensive, the Nazis started tattooing numbers on the inmates’ arms. Those who were not selected for the barracks were told they were to take showers. Only Zyklon-B gas was used instead. (The shower heads are still embedded in the cement wall). From there, their bodies were taken to the crematorium The Nazis destroyed evidence of the gas mass killings by blowing up the buildings. Anya told us they liked to use gas because they didn’t have to look at the person while he was being killed.

Those who were not selected for the barracks were told they were to take showers. Only Zyklon-B gas was used instead. (The shower heads are still embedded in the cement wall). From there, their bodies were taken to the crematorium The Nazis destroyed evidence of the gas mass killings by blowing up the buildings. Anya told us they liked to use gas because they didn’t have to look at the person while he was being killed. This was confirmed by Jerzy Kowalewski, an eighty-eight-year-old Auschwitz survivor. We attended a seminar he had given in Warsaw.

This was confirmed by Jerzy Kowalewski, an eighty-eight-year-old Auschwitz survivor. We attended a seminar he had given in Warsaw. At the daily roll call, the entire camp stood in their meager rags as the SS guards called out their names. The roll call was given as a collective punishment for the wrongdoing of just one prisoner. The inmates stood for up to four hours in the rain and snow. Some of the extremely weak and sick prisoners would die in the lines during the roll call. After roll call, the prisoners received their ration for breakfast. They were given 10 ounces of bread with a small piece of salami or one ounce of margarine and brown, weak coffee, with no sugar.

At the daily roll call, the entire camp stood in their meager rags as the SS guards called out their names. The roll call was given as a collective punishment for the wrongdoing of just one prisoner. The inmates stood for up to four hours in the rain and snow. Some of the extremely weak and sick prisoners would die in the lines during the roll call. After roll call, the prisoners received their ration for breakfast. They were given 10 ounces of bread with a small piece of salami or one ounce of margarine and brown, weak coffee, with no sugar.

In the Block (or Building 5), on either side of the middle aisle, behind glass, were piles fifteen feet high of human hair on both sides. Rows of long braids popped out at me first.

In the Block (or Building 5), on either side of the middle aisle, behind glass, were piles fifteen feet high of human hair on both sides. Rows of long braids popped out at me first.

My wife and I are on a Mediterranean cruise along the coasts of Italy and France celebrating our 20th anniversary, sailing on the ultra-deluxe Norwegian ship. Sea Dream I, which carries just over 100 passengers. Sea Dream I is a magic carpet, easing us in comfort and style through a region full of fascinating history. We have been anticipating visits to some wonderful ports and are not disappointed. What we had not foreseen, though, is the many ways that Napoleon, or perhaps just his spirit, would keep making his presence felt, as if popping up unexpectedly in little cameo appearances. These underscore just how completely he dominated Europe in his brief but dramatic era of war and conquest, supreme glory and abject defeat.

My wife and I are on a Mediterranean cruise along the coasts of Italy and France celebrating our 20th anniversary, sailing on the ultra-deluxe Norwegian ship. Sea Dream I, which carries just over 100 passengers. Sea Dream I is a magic carpet, easing us in comfort and style through a region full of fascinating history. We have been anticipating visits to some wonderful ports and are not disappointed. What we had not foreseen, though, is the many ways that Napoleon, or perhaps just his spirit, would keep making his presence felt, as if popping up unexpectedly in little cameo appearances. These underscore just how completely he dominated Europe in his brief but dramatic era of war and conquest, supreme glory and abject defeat. The next planned destination is the Italian island of Elba, the one place where we would expect to find sites intimately linked to Napoleon’s life. It was on Elba that he was forced into exile (along with about 1000 servants and troops as bodyguards) after a series of defeats in 1814.

The next planned destination is the Italian island of Elba, the one place where we would expect to find sites intimately linked to Napoleon’s life. It was on Elba that he was forced into exile (along with about 1000 servants and troops as bodyguards) after a series of defeats in 1814. Then we anchor off Viareggio, back on the Italian coast in Tuscany, and take a day trip inland to Florence. We have arranged a walking tour to enjoy the glorious and stunning medieval and Renaissance architecture, monumental public sculptures and inviting pedestrian-only piazzas. It is far too brief, of course, but our personal guide takes us to some special places, such as the studio of a blacksmith who creates fantastic birds, fishes and other creatures in steel, and to the guide’s own favourite and funky “Cafe of the Artisans.” We stroke the snout of an iconic bronze wild boar and share a kiss, thus assuring our return to Florence some day.

Then we anchor off Viareggio, back on the Italian coast in Tuscany, and take a day trip inland to Florence. We have arranged a walking tour to enjoy the glorious and stunning medieval and Renaissance architecture, monumental public sculptures and inviting pedestrian-only piazzas. It is far too brief, of course, but our personal guide takes us to some special places, such as the studio of a blacksmith who creates fantastic birds, fishes and other creatures in steel, and to the guide’s own favourite and funky “Cafe of the Artisans.” We stroke the snout of an iconic bronze wild boar and share a kiss, thus assuring our return to Florence some day. Farther north on the Italian Riviera, our ship anchors off the picturesque village of Portofino, with its brightly painted old houses. Once a simple fishing village, it now has an upscale yacht harbour catering to the rich and famous. Going ashore for a few hours, we hike up to a striking castle that dominates the small bay. And sure enough, Napoleon left his mark here as well during the years when France controlled northern Italy. What we see is an ancient fortification that Napoleon modernized, greatly expanded and equipped with better cannons. Not one for modesty, he renamed the village Port Napoleon.

Farther north on the Italian Riviera, our ship anchors off the picturesque village of Portofino, with its brightly painted old houses. Once a simple fishing village, it now has an upscale yacht harbour catering to the rich and famous. Going ashore for a few hours, we hike up to a striking castle that dominates the small bay. And sure enough, Napoleon left his mark here as well during the years when France controlled northern Italy. What we see is an ancient fortification that Napoleon modernized, greatly expanded and equipped with better cannons. Not one for modesty, he renamed the village Port Napoleon. While a student, I had bunked at a unique youth hostel in a little modern castle overlooking Finale Ligure, a lovely stretch of coastal villages on the Italian Riviera only an hour east of Monaco. We decide to return to explore those intriguing shores, with their rich and diverse history. It was here that the 15-year-old Margaret Theresa of Spain stopped briefly in 1666 while on her way to Vienna to marry Leopold I, the Holy Roman Emperor. A triumphal arch commemorating the event dominates the central piazza, not far from ancient fortifications that marked the long-fought-over boundary between Spanish and Genoese-controlled territories. A few miles east is the village of Varigotti with its strikingly Moorish houses. These were built in the ninth and tenth centuries by the Muslim Saracens, who ruled the area for nearly 100 years. Long thereafter, they remained both a threat and a trading partner to the region, bringing such goods as salt from Ibiza when Spain was still under Moorish rule.

While a student, I had bunked at a unique youth hostel in a little modern castle overlooking Finale Ligure, a lovely stretch of coastal villages on the Italian Riviera only an hour east of Monaco. We decide to return to explore those intriguing shores, with their rich and diverse history. It was here that the 15-year-old Margaret Theresa of Spain stopped briefly in 1666 while on her way to Vienna to marry Leopold I, the Holy Roman Emperor. A triumphal arch commemorating the event dominates the central piazza, not far from ancient fortifications that marked the long-fought-over boundary between Spanish and Genoese-controlled territories. A few miles east is the village of Varigotti with its strikingly Moorish houses. These were built in the ninth and tenth centuries by the Muslim Saracens, who ruled the area for nearly 100 years. Long thereafter, they remained both a threat and a trading partner to the region, bringing such goods as salt from Ibiza when Spain was still under Moorish rule.