by W. Ruth Kozak

On a bright May afternoon, I travel by train across the lush Thessaly Plain in central Greece, through the valley of the Pinios River.

Green fields are patched with crops of yellow mustard, and splashes of brilliant red poppies carpet upland meadows where flocks of sheep graze idly in the sun. Across the Plain, sunlight glitters off the snow-covered peaks of Mounts Pelion and Parnassus. An eagle soars above a distant crag. Suddenly, out of the plain, gigantic spires of rock emerge, some higher than 400 meters, their strange shapes jutting up out of the fertile soil. Nothing I have seen in pictures has prepared me for this sight. Few places I have seen in Greece are so intensely dramatic.

Green fields are patched with crops of yellow mustard, and splashes of brilliant red poppies carpet upland meadows where flocks of sheep graze idly in the sun. Across the Plain, sunlight glitters off the snow-covered peaks of Mounts Pelion and Parnassus. An eagle soars above a distant crag. Suddenly, out of the plain, gigantic spires of rock emerge, some higher than 400 meters, their strange shapes jutting up out of the fertile soil. Nothing I have seen in pictures has prepared me for this sight. Few places I have seen in Greece are so intensely dramatic.

Like the pastel escarpments in a Chinese watercolour, the towering rock fingers reach up to the cloudless sky. Their name, “Meteora,” means suspended in air. The most incredible feature of the Meteora are the monasteries that cling to the summits where once only eagles built nests. Five hundred years ago, at the end of the Byzantine era, during Turkish rule, this wild terrain became the refuge of pious men who fled religious oppression. Sheltered from the world, living in solitude and privation, the monks aimed to achieve Christian perfection.

Six hours from Athens, the train stops at Kalambaka on the edge of the Plain, below the Meteora. Here I find reasonable accommodation and set off to explore the hills behind the town, following a goat trail that winds toward the strange rock giant. In the warm pinkish glow of sunset, the huge rocks are suffused with an aureole of pale mysterious light. Alone, with only the sounds of nature, I contemplate the awesome sigh and cannot help but wonder how many solitary monks left their bones there, forgotten by the world they had renounced.

Early next morning, I ride up to the Meteora in the small bus provided for tourists. The road passes the village of Kastraki and winds past the rock pinnacles where you can see the remains of ascetics’ caves, many walled off with rocks and rotting timbers.

Early next morning, I ride up to the Meteora in the small bus provided for tourists. The road passes the village of Kastraki and winds past the rock pinnacles where you can see the remains of ascetics’ caves, many walled off with rocks and rotting timbers.

In the past, chain and rope ladders were the only way to reach the 24 monasteries here at the height of the 17th century, of which only six remain. If someone fell, it was God’s will. The charnel house at the Grand Meteora is a grisly reminder of those who died: their skulls line the dusty shelves. Today, visitors can climb steps cut from rocks and cross wooden bridges over dizzying chasms. Rock climbers come from around the world to scale the pillars.

The first monastery you see as you approach is St Nicholas Anapafsas, built in 1527. It clings to the top ledge of an enormous rock. Uninhabited for years, its superb wall paintings by artist-monk Theophanes have now been restored.

The first monastery you see as you approach is St Nicholas Anapafsas, built in 1527. It clings to the top ledge of an enormous rock. Uninhabited for years, its superb wall paintings by artist-monk Theophanes have now been restored.

The Monastery of the Transfiguration, also known as the Grand Meteora, is like a multi-storied castle complete with a bell-tower and red-tiled roof. It stands 700 meters above sea level and is reached by a flight of 115 irregular steps cut into the rock face.

A white-bearded monk directs the tour. He begins with the museum where there are invaluable icons and ceremonial vestments. He explains that during Byzantine times, these monasteries were generously endowed by Greek royalty, who regarded it their duty to donate riches and land to the Church. As a result Grand Meteora became one of the most important religious communities in the region.

Reached by climbing 195 steps, the Monastery of Varlaam, next to the Grand Meteora, has a church elaborately decorated by the famous hagiographer, Franco Catallano as well as a library with priceless manuscripts and gospels.

Agia Tria, the Holy Trinity, built by the monk Dometius in the late 1400s, is on a pinnacle reached by a circular flight of 140 steps. The view is staggering. I feel suspended in a breathless void.

Agia Tria, the Holy Trinity, built by the monk Dometius in the late 1400s, is on a pinnacle reached by a circular flight of 140 steps. The view is staggering. I feel suspended in a breathless void.

Between the summit of the Holy Trinity and Varlaam, Roussanou perches on an isolated precipitous rock. Linked to the rocks next to it and reached by another circular flight of 140 steps, Agios Stephanos is a small dark place with wooden ceilings. Today, about 24 nuns live here and at the Roussanou monastery.

In Meteora, the spiritual world matters, not physical life. I look out across the plain toward the hazy summits of the Pindos Mountains. I see and feel how the landscape reflects the monks’ life, lonely yet inspirational. Despite the stream of tourists and souvenir stands, high atop these isolated rocks you can still sense the presence of God.

If You Go:

Train: There are trains from Thessaloniki and Athens. From Athens the trip is about six hours to Kalambaka. Change trains in Paleofarsala.

Buses: from Athens, Thessaloniki and Ioannina to Kalmabaka and Kastraki.

By Car: from Athens (350 kms) about 5 hours or from the north along E 87 between Ioannina and Larissa.

Visiting the Monasteries: It is only a short walk between entrances to the monasteries, but you need a good set of legs. A bus service runs from Kalambaka. There is a small entrance fee at the monasteries. Plan to spend a full day. Check ahead as some are only open certain days. Until this century women were not allowed in the monasteries. Today women are admitted if modestly dressed. Sleeveless tops, shorts, min-skirts and pants are forbidden. Floor-length skirts and shawls provided at the entrance. Tank tops and shorts are not acceptable for men. Dress appropriately or you will not be admitted. Pay attention to signs regarding photos as in some areas taking pictures is not allowed.

Accommodation:

There are several pensions and moderately priced hotels in both Kalambaka and Kastraki. There is a campsite at Kalambaka, the closest village.

Best Times to Go:

December – March can be wet and cool.

May and June are the most ideal months to visit.

July 1 – mid-October is the high season.

On The Web:

www.great-adventures.com

www.sacred-destinations.com

www.greecetravel.com

www.greeka.com

About the author:

W. Ruth Kozak is the former editor of Travel Thru History. She spent many years both living in and visiting Greece, and during those times she visited the astonishing sights of Meteora twice. This is a unique area of Greece, and she recommends it as a special destination if you plan to holiday there.

Photo credits:

Meteora Valley by Wisniowy / CC BY-SA

All other photos by Ruth Kozak

However, it’s not quite as dire as it sounds for Kermit and Jeremy Fisher as they have nothing to fear these days: The Frog Museum in Estavayer-le-Lac is not looking for new acquisitions. The fact of the matter is that the museum’s prized holdings were actually created in the 1850’s by an eccentric Napoleonic guard officer. Francois Perrier, reputedly an officer and a gentleman, had a fascination for frogs and collected them while on walks through the countryside. He also had too much time on his hands: Perrier would take his collection of frogs home, extract the innards through their mouths, and then stuff the hollow skin with sand, all the while modeling and dressing the frog corpses in uncanny human dioramas of scenes from everyday life.

However, it’s not quite as dire as it sounds for Kermit and Jeremy Fisher as they have nothing to fear these days: The Frog Museum in Estavayer-le-Lac is not looking for new acquisitions. The fact of the matter is that the museum’s prized holdings were actually created in the 1850’s by an eccentric Napoleonic guard officer. Francois Perrier, reputedly an officer and a gentleman, had a fascination for frogs and collected them while on walks through the countryside. He also had too much time on his hands: Perrier would take his collection of frogs home, extract the innards through their mouths, and then stuff the hollow skin with sand, all the while modeling and dressing the frog corpses in uncanny human dioramas of scenes from everyday life. With that being said; nevertheless, there’s something compelling about a Swiss medieval town noted for its obsession with stuffed frogs (they are actually a tannish-brown instead of green) composed of skin and sand. Behind glass and meticulously preserved, the vignettes are parodies of human life in the 19th century. The frogs do human things like playing cards and dominoes, shooting billiards, feasting at a long table, eating spaghetti at a smaller table, getting a haircut at the barbershop, sitting at a desk in an old-fashioned schoolroom…and then there’s my favorite conundrum…a frog mounted on top of a squirrel, riding the furry rodent like a cavalry soldier might ride a horse.

With that being said; nevertheless, there’s something compelling about a Swiss medieval town noted for its obsession with stuffed frogs (they are actually a tannish-brown instead of green) composed of skin and sand. Behind glass and meticulously preserved, the vignettes are parodies of human life in the 19th century. The frogs do human things like playing cards and dominoes, shooting billiards, feasting at a long table, eating spaghetti at a smaller table, getting a haircut at the barbershop, sitting at a desk in an old-fashioned schoolroom…and then there’s my favorite conundrum…a frog mounted on top of a squirrel, riding the furry rodent like a cavalry soldier might ride a horse. Whether you reel back cautiously from the ludicrously odd or openly admire Perrier’s masterpiece of taxidermy and his tableau interpretations, one thing is for certain: It is an unusual tribute to anthropomorphic art and a social commentary on life in his times.

Whether you reel back cautiously from the ludicrously odd or openly admire Perrier’s masterpiece of taxidermy and his tableau interpretations, one thing is for certain: It is an unusual tribute to anthropomorphic art and a social commentary on life in his times.

Composed of sleepers, a dining car and a baggage car, the train featured Lalique chandeliers, a piano and the finest crockery and cutlery. The maiden journey started on October 10th 1882 in Paris and reached Istanbul the next day. The menu consisted of no less than seven courses, oysters and turbot in green sauce included, not to mention fine wines and champagne. In 1977 the train ceased to have Istanbul as its final destination and in 2009 the Orient Express disappeared entirely from the time tables. Several other routes continue though and twice a year the historical trip is repeated, at a very stiff price!

Composed of sleepers, a dining car and a baggage car, the train featured Lalique chandeliers, a piano and the finest crockery and cutlery. The maiden journey started on October 10th 1882 in Paris and reached Istanbul the next day. The menu consisted of no less than seven courses, oysters and turbot in green sauce included, not to mention fine wines and champagne. In 1977 the train ceased to have Istanbul as its final destination and in 2009 the Orient Express disappeared entirely from the time tables. Several other routes continue though and twice a year the historical trip is repeated, at a very stiff price! The pink and white structure of the railway station is located in Eminönü on the shores of the Bosporus. Designed by German architect August Jachmund, it’s the best example of European Orientalism, combining elements of Ottoman architecture with modern amenities such as gas and later electric lighting and heating in winter.

The pink and white structure of the railway station is located in Eminönü on the shores of the Bosporus. Designed by German architect August Jachmund, it’s the best example of European Orientalism, combining elements of Ottoman architecture with modern amenities such as gas and later electric lighting and heating in winter. It’s only one room, but the museum documents the history of the Orient Express and the train station in detail. Old log books are displayed as are conductors’ uniforms, the piano, a table laid with the original cutlery and crockery, tickets and many more memorabilia. Photographs adorn the walls and examples of the technology of the time are on display too. I loved the newspaper clipping of when the train got stuck in a snow storm in Bulgaria, very reminiscent of the plot of Agatha’s novel. Admission is free and you are allowed to take as many photographs as you want.

It’s only one room, but the museum documents the history of the Orient Express and the train station in detail. Old log books are displayed as are conductors’ uniforms, the piano, a table laid with the original cutlery and crockery, tickets and many more memorabilia. Photographs adorn the walls and examples of the technology of the time are on display too. I loved the newspaper clipping of when the train got stuck in a snow storm in Bulgaria, very reminiscent of the plot of Agatha’s novel. Admission is free and you are allowed to take as many photographs as you want.

As affluent Europeans started to descend upon romantic Istanbul, using the Orient Express, they needed an equally elegant place to rest their heads. The city was decidedly short of such type of establishment and that’s how the Pera Palace was conceived. The first super luxury hotel of Istanbul, located in fashionable Beyoglu (then called Pera) opened its door with an inaugural ball in 1892.

As affluent Europeans started to descend upon romantic Istanbul, using the Orient Express, they needed an equally elegant place to rest their heads. The city was decidedly short of such type of establishment and that’s how the Pera Palace was conceived. The first super luxury hotel of Istanbul, located in fashionable Beyoglu (then called Pera) opened its door with an inaugural ball in 1892. Not carried by a sedan but using the tramway running up and down Istaklal Street, I made my way on foot to the Pear Palace. The hotel was closed for nearly four years, undergoing extensive renovations but is now open again. No better place to get a feel for how people traveled in the past than sitting in the Orient Bar, enjoying a cocktail.

Not carried by a sedan but using the tramway running up and down Istaklal Street, I made my way on foot to the Pear Palace. The hotel was closed for nearly four years, undergoing extensive renovations but is now open again. No better place to get a feel for how people traveled in the past than sitting in the Orient Bar, enjoying a cocktail.

One week didn’t seem like a lot of time, my host at the residency pointed out, after circumstances required I cut my stay by a week. But it turned out to be one of the most productive for my writing in a long time. The residency, located just outside Aureille, provided plenty of uninterrupted time for reading, thinking, and writing, all of which I did copiously.

One week didn’t seem like a lot of time, my host at the residency pointed out, after circumstances required I cut my stay by a week. But it turned out to be one of the most productive for my writing in a long time. The residency, located just outside Aureille, provided plenty of uninterrupted time for reading, thinking, and writing, all of which I did copiously. I spent my second day working on a short story, the concept for which I had been nursing for a while. The entire day, off and on, was spent working on this, and by the evening I was pleased to have finished the first draft. As I lay in bed that night, I contemplated how best to revise and improve my story. Falling asleep, however, did not follow naturally. My hosts keep no locks on their doors, since apparently in Aureille crime is practically unheard of. Unlocked doors always appear like an invitation to trouble for me and I braced the handle of my bedroom door with a chair and kept one of the lights burning to allow me a little peace of mind and some sleep.

I spent my second day working on a short story, the concept for which I had been nursing for a while. The entire day, off and on, was spent working on this, and by the evening I was pleased to have finished the first draft. As I lay in bed that night, I contemplated how best to revise and improve my story. Falling asleep, however, did not follow naturally. My hosts keep no locks on their doors, since apparently in Aureille crime is practically unheard of. Unlocked doors always appear like an invitation to trouble for me and I braced the handle of my bedroom door with a chair and kept one of the lights burning to allow me a little peace of mind and some sleep. That evening the hosts held a dinner for the artists around the pool. They wanted to hear my story that I had unfortunately been unable to present at the conference in Wales, having fallen ill. The warm approval on everyone’s faces and their requests to hear the story I was currently working on at the residency even though it was unpolished told me that perhaps I do have something to offer as a writer.

That evening the hosts held a dinner for the artists around the pool. They wanted to hear my story that I had unfortunately been unable to present at the conference in Wales, having fallen ill. The warm approval on everyone’s faces and their requests to hear the story I was currently working on at the residency even though it was unpolished told me that perhaps I do have something to offer as a writer.

The following morning it was time to leave the residency. As I disposed of the garbage from my apartment, Angela, a Northern Irish artist who was also staying at the residency, was standing outside drinking her morning coffee. She asked me for my last name and thanked me for having shared my short story with the other artists on Saturday evening. “I will look out for your name,” she told me.

The following morning it was time to leave the residency. As I disposed of the garbage from my apartment, Angela, a Northern Irish artist who was also staying at the residency, was standing outside drinking her morning coffee. She asked me for my last name and thanked me for having shared my short story with the other artists on Saturday evening. “I will look out for your name,” she told me.

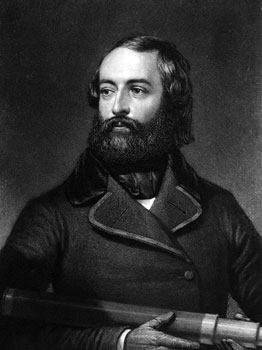

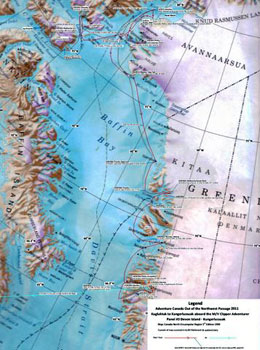

But on September 10, one day after it did so, we sailed into Rensselaer Bay, where in the mid-1850s, explorer Elisha Kent Kane spent two terrible winters trapped in the ice. And three days after that, as on Day Thirteen of our voyage we approached the island town of Upernavik, I went to the bridge. As the staff historian, I needed to announce the surprising news.

But on September 10, one day after it did so, we sailed into Rensselaer Bay, where in the mid-1850s, explorer Elisha Kent Kane spent two terrible winters trapped in the ice. And three days after that, as on Day Thirteen of our voyage we approached the island town of Upernavik, I went to the bridge. As the staff historian, I needed to announce the surprising news. What drove me to the bridge was that our voyage had just become the first to trace Kane’s escape route from Rensselaer Bay to Upernavik, where Danish settlers welcomed the explorer, and now their posterity welcomed us.

What drove me to the bridge was that our voyage had just become the first to trace Kane’s escape route from Rensselaer Bay to Upernavik, where Danish settlers welcomed the explorer, and now their posterity welcomed us. The change gave us extra time. We hoped now to sail north through Smith Sound into Kane Basin. Perhaps we could reach Etah on the west coast of Greenland, situated at a northern latitude of 78 degrees 18 minute 50 seconds. Etah was as far north as Adventure Canada had yet ventured along “the American route to the Pole.”

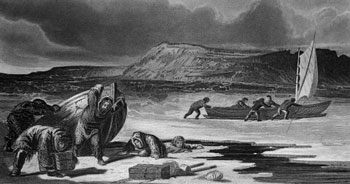

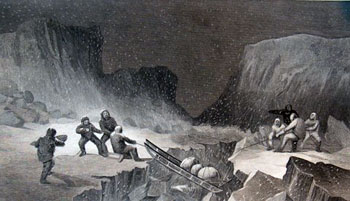

The change gave us extra time. We hoped now to sail north through Smith Sound into Kane Basin. Perhaps we could reach Etah on the west coast of Greenland, situated at a northern latitude of 78 degrees 18 minute 50 seconds. Etah was as far north as Adventure Canada had yet ventured along “the American route to the Pole.” While most voyagers went ashore in zodiacs to explore beaches and ridges, five of us — an archaeologist, a geologist, an artist-photographer, an outdoorsman, and an author-historian (yours truly) — spent three hours searching small rocky islands for relics of Kane’s expedition. We found what I believe to be the remains of his magnetic observatory. And from the zodiac, prevented from scrambling onto slippery rocks by a receding tide, we spotted what I believe to be the site on “Butler Island” where Kane buried the bodies of two of his men.

While most voyagers went ashore in zodiacs to explore beaches and ridges, five of us — an archaeologist, a geologist, an artist-photographer, an outdoorsman, and an author-historian (yours truly) — spent three hours searching small rocky islands for relics of Kane’s expedition. We found what I believe to be the remains of his magnetic observatory. And from the zodiac, prevented from scrambling onto slippery rocks by a receding tide, we spotted what I believe to be the site on “Butler Island” where Kane buried the bodies of two of his men. Ice conditions here have always been difficult and unpredictable. And in recent decades, recorded visits have been few. A 1984 article in Arctic magazine describes a study undertaken by scientists who helicoptered in from the American airbase at Thule to investigate the long-term decline in the caribou population. And an exhaustive archaeological study of northwest Greenland by John Darwent and others, detailed in Arctic Anthropology in 2007, turned up 1,376 features, including winter houses, tent rinks and burials — but sought and discovered no bodies in Rensselaer Bay.

Ice conditions here have always been difficult and unpredictable. And in recent decades, recorded visits have been few. A 1984 article in Arctic magazine describes a study undertaken by scientists who helicoptered in from the American airbase at Thule to investigate the long-term decline in the caribou population. And an exhaustive archaeological study of northwest Greenland by John Darwent and others, detailed in Arctic Anthropology in 2007, turned up 1,376 features, including winter houses, tent rinks and burials — but sought and discovered no bodies in Rensselaer Bay. In Kane’s time, Etah was a permanent Inuit settlement, home to several extended families. Today, it serves as a temporary hunting camp. We stayed six hours and hiked to Brother John Glacier, a natural wonder that Kane, oblivious to Inuit nomenclature, named after his dead sibling.

In Kane’s time, Etah was a permanent Inuit settlement, home to several extended families. Today, it serves as a temporary hunting camp. We stayed six hours and hiked to Brother John Glacier, a natural wonder that Kane, oblivious to Inuit nomenclature, named after his dead sibling. On the Clipper Adventurer, dining variously on Greenland halibut, veal marsala, and braised leg of New Zealand lamb, we retraced Kane’s perilous voyage in two days. We called in at Cape York, where the explorer overcame a last great barrier of protruding shore ice, and from there gazed out over open water.

On the Clipper Adventurer, dining variously on Greenland halibut, veal marsala, and braised leg of New Zealand lamb, we retraced Kane’s perilous voyage in two days. We called in at Cape York, where the explorer overcame a last great barrier of protruding shore ice, and from there gazed out over open water.