by Georges Fery

The Lambayeque region in northern Peru is home to cultures as great as any other that emerged in the country’s Pacific Coast and in the Andes Mountains. One of them is the Chachapoya, whose history arose east of Chiclayo in the rugged and remote northwestern province of Amazonas, bounded by the Marañón River valley to the north and west, and the Huallaga River to the south and east. Between these large rivers, affluents of the powerful Amazon, lies the Utcubamba valley, where the citadel of Kuélap was built ten thousand feet up in the northern Andes mountains.

The Chachapoyas’ origins are uncertain, but they are believed to have migrated centuries ago, probably from Ecuador’s Amazon rain forest. Moving west, they crossed the mighty and dangerous Marañón (or Atunmayo River), a tributary of the Amazon, whose challenging power made their return hazardous. For this reason and because of their relative isolation, the Chachapoyas are a little-known ethnic group among the ancient societies of the Andes.

Ruiz comments that the culture appears to have developed sometimes between the seventh and ninth centuries (1972). Sometime after that, at a cultural crossroads that once connected villages on the northeastern slopes of the Andes, the Chachapoyas developed trade with the cultures of the Amazon and with those on the lower western slopes of the Andes. Remains of their and ancient villages (ayllus) and structures are found, between the Marañón and the Huallaga rivers.

The timeline of the Chachapoyas called “Warriors of the Clouds” by scholars for their remote location in the tropical jungle-clad mountains of the norther Andes, points to interactions with the Chimú (900-1470) and other cultures on northern Peru’s Pacific Coast (unless otherwise noted, all dates are AD/CE). They were followed by the Quechua (Runasimi) speakers from the central Andes around the late 900s (Lathrap,1970; Isbell, 1974). The new arrivals cultivated maize on artificial stepped terraces at select elevations, but favored settlement locations on high defensible ridge tops, between seven thousand and eleven thousand feet. The geographic limits for the people we call Chachapoya, however, have never been clearly defined (Bradley, 2005). They were later conquered by the Incas, who appear to have given them the name Chachapoyas, since there is no record of their original name in the local language.

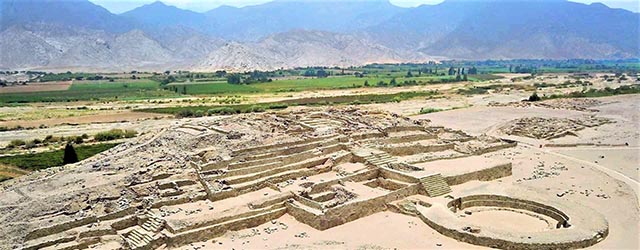

It is during the mid-fifteenth century that the tenth Sapa-Inca, Tupac Inca Yupanqui (1471-1493), the son of the great Pachacuti, conquered the Chachapoyas and forcibly transferred local villagers under the Inca system of forced resettlement of conquered people to other parts of the empire known as mitmaq. Archaeologist Federico Kauffmann Doig (2017) describes the citadel built on two large and levelled platforms on the ten thousand feet high plateau called La Barreta that overlooks much of the Utcubamba river valley. La Barreta is two thousand feet long by five hundred feet wide, narrowing down to less than a hundred feet in parts of its length. A seventy feet high stone wall surrounds most of the plateau.

The citadel’s location, in the area’s cold and windy climate, was ideal as a storage facility for grains, other dry foodstuff and possibly, for short-time storage, dehydrated meat. It was also dedicated to the local animist cult, with buildings for permanent residents such as priests, civic leaders, and service staff. The circular structures were built for storage. They have no openings for either doors or windows; however, several were found to have small access ramps. The cone-shaped roofs were made of natural fibers tied onto a wood frame. There were openings for both access to storage from the top and ventilation at ground level to let in the dry mountain air. The reason for such a large food storage complex was primarily to answer periods of bad crops, among which were those generated by El Niño and La Niña climate events, which periodically decimated coastal and highland cultures. Each farmer may have contributed to a set quantity of products from their crops for storage under a levy or tax system.

Kuélap is built in concentric tiers within which are over five hundred densely packed structures enclosed by the site’s outer wall, which is seventy-feet-high in its highest section (Narváez, 1996). Within the complex are several groups of circular buildings, as well as five square ones that may have housed administrators and service staff. Among the structures is the Atalaya, a forty-foot-high rectangular stone tower. Located at the northern low end of the plateau, it was a lookout post as well as a bastion from which to defend the site from attack along this lowest part of the ridge (Muscutt, 1993). At the opposite end of the site is an unusual circular structure called the Tintero (inkwell) for its inverted conical shape with sides flaring outward at its top. The neck of the inkwell forms a chimney that can only be accessed from above.

James McGraw, from the San Diego Museum of Man, noticed that the chimney is not fully vertical but deliberately tilted. Its dimensions corelate with the sun at noon on the day of the winter solstice, a key day in Andean rituals for agricultural cycles. At that time, the sun rays shine down the Tintero‘s top opening and projects a beam of light onto its floor. At its bottom were carved stones that may have served to track the movement of the sun, making the structure a solar calendrical observatory (Muscutt, 1993). Geometrical pattern motifs are found on select structures, together with representations of the jaguar and the serpent, both symbols found in most ancient cultures of the Americas. The jaguar is the dominant life form in most domains by day or night, while the serpent is associated with nature’s rebirth, witnessed by the periodic shedding of its skin (molting).

When Bandelier (1907) and Langlois (1934) visited Kuélap, they noted that many of the niches in the buildings were used as open graves, for they found human remains on the outside of their walls, making the site both a living and a mortuary community. Even though the context for many of these burials is unknown, recent excavations have revealed the presence of many entombments within the site’s walls. Archaeologist Narváez, after counting over a hundred such burials, concluded that “in reality the outer wall is a cemetery” (1988). Recent excavations suggest that other burials could still be found within the site’s walls. Two trapezoidal entryways, about two hundred feet long and ten feet wide at the entry point, allowed access to the citadel. However, their width narrows down to allow only one person at a time to enter the guarded gate to the central plaza (Narvaez, 1988). A third narrow corridor opens west; it is difficult to access from the outside and was probably used to discard material in a ravine below.

Who built Kuélap is uncertain, for archaeological evidence is scant (Muscutt, 1998). Earlier dates indicate that it might have been originally conceived for defense against the expansion of the Chimú Empire, which exerted control over much of the central highlands (Kauffmann Doig, 1998). The site was likely visible from agricultural fields that lie west of the Utcubamba river. Church and Von Hagen report that many of the large communities that lie to the west of the citadel are in locations directly visible from the site’s outer walls (2007), such as the town of Chillo, in Kuélap’s shadows. The remains within the citadel’s walls were in all probability those of select ancestors of people living in nearby villages. Crandall points out that the social relationship between ancestor remains and living people, was an ongoing set of practices designed to reaffirm social ties to the ayllu or kin group (2012).

Based on Ruiz’s association (1972), the monumental construction and tombs probably began around the year 900. Southern sites, however, such as Gran Pajatén, Los Pinchudos and Revash, in today’s Rio Abiseo National Park, were occupied in Inca times (Bonavia, 1968, Church, Von Hagen, 2008). Other larger regional centers, besides Kuélap, appear to have developed between the eighth and tenth centuries. In the late nineteen-nineties, the area south of Leymebamba received much attention when pre-Columbian chullpas, (mausoleums or funeral houses), were found at Revash, fifty-two miles from Kuélap in the surrounding hills around Gran Pajatén, which may have been built at the height of the Chachapoya cultural florescence in the first millennium.

The citadel is an imposing socio-economic and religious complex, whose purposes were like those of other smaller sites. The common denominator with those sites is the prevalence of ancestor remains, which are found in either a coffin or wrapped up in funerary bundles placed in mausoleums. As Crandal (2012) notes, Chachapoya ontology, akin to other Andean people, was predicated on a collective relationship to ancestors who played an active role in reproducing social life. Coffins are called purunmatshus in the local language and were made to receive a single individual. The erect purunmatshus of Karajia in Luya province, are among the most eminent. They are found in large recesses carved in an abrupt rock face, that creates a rocky overhang, thus shielding them from the rain and helping in their preservation.

Their isolated location and overhang were at times insufficient against birds and rodents. The ones shown were studied by Kauffmann Doig and his teams during their field research which spanned from the late-1970s to the mid-2000s. The Karajia purunmatshus were found 985 feet up the rock wall overlooking the Aispacha River, each holding a family member or close relative. The coffins are made of clay mixed with natural fibers set on a wood frame; they portray a human shape that, at over eight feet in their upright position, is impressive.

Their appearance is chiefly due to the modeling of their heads and faces, the only anatomical reference to a human body. Their faces and bodies are painted with yellow, tan, and dark ochre designs that make them appear surrealistic and underline that they are men. Even though a few stands alone, they are commonly found in groups of four to ten standing on a thick mud base.

A space between the line of coffins at Karajia, shows that there were originally eight purunmatshus in the original group, but one of them (No.3), is recorded to have fallen in the river below during the violent 1928 earthquake (Kauffmann Doig, 2002). Above their heads, a mummified human skull was held in place by a spike. Of note, however, is that the skull did not belong to the individual inside the purunmatshu but is from another party. We have no record of, nor do we know the reason why the mummified skull was placed there. Was it to record the hierarchical status of the departed? Neither do we have a history of the ancestors’ identities who, according to the collective memory of local people, point to ancestors of the mythic Ocspalin, a cacique or chief of the Conila’s ayllu or community who built the bridge with the people over the Aispachar River. Why were the standing coffins placed in inaccessible locations? It seems that it was not so much to avoid eventual plunder, for at that time ancestors from all segments of society were fearfully respected and so were their resting places. The reason may be linked to the fact that those select ancestors were believed to hold powerful spiritual powers in the “other world.” At times, ancestors may raise the wrath of malevolent forces for the actions of their descendants.

In ancient Peru, the purunmatshus were only used by the Chachapoyas in their territory on the left bank of the Utcubamba river. Kauffmann Doig, in 1986, identified six types spanning from the sophisticated Type.A or Purunmatshu Regio at Karajia, to Types.B, C and D which varied through time and locations. The distinctive feature of B, C and D, is the migration through time of the head, made of compact clay on top of a stocky ovoid body without neck, to the chest and later to the belly. The absence of head applies to the more recent cone shaped Type.E, while Type.F is referred to as a pseudo-sarcophagus for it is made of a semi-circular, four-feet-high wall made of clay placed in front of a rock face where, within the enclosure, bundled up mummies were found. In Type.A, the mummified body inside was tightly wrapped in fine llama wool blankets in a seating or squatting position (the similarity with Wari mummies is striking), with small ceramics and stone votive items placed between the wrappings and at the feet of the ancestor.

In mid-fifteenth century, the Chachapoyas were incorporated into the Inca “Realm of the Four Parts” (the Tahuantinsuyu in Quechua), under the “son of the Sun” the great Sapa-Inca in Cuzco, Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (1418-1471). Pachacuti organized the kingdom into four regions or suyu: northwest, northeast, southwest and southeast, with Cuzco at the center. His son Topa Inca Yupanqui (1441-1493) would eventually extend the Tahuantinsuyu along the Pacific Coast to today’s western Ecuador, south central Bolivia, northwest Argentina, and most of Chile to the south. But before that, in the mid-fifteenth century the Sapa Inca conquered the powerful Chimú Empire on Peru’s north coast; his army then turned inland toward the Andes. The northeast (antisuyu) territory extended deep into the eastern slopes of the mountain range which was covered by a dense tropical forest. Garcilaso de la Vega (1539-1616) wrote that the Inca invasion of the Chachapoya territory started in the mid-1450s. The invaders went through repeated hard-fought battles in the challenging topography, but the Chachapoyas fought hard and were never defeated. The account does not include Kuélap which may have been bypassed by the Inca armies. Historical sources relate that by the 1460s, after months of relentless battles and deadlocks, the Chachapoyas had no option but to concede to a bitter peace agreement. In accordance with the empire’s rules of occupation, Cuzco sent civil servants and army officers to oversee the territory’s towns and villages.

This is Part 1 of a 2 Part series. Read Part 2 here.

References – Further Reading:

Federico Kauffmann Doig, 2017 – La Cultura Chachapoyas

Keith Muscutt, 1998 – Warriors of the Clouds

Federico Kauffmann Doig, 2009 – Construcciones de Kuélap y Pajatén

James M. Crandall, 2012 – Chachapoya Eschatology: Spaces of Death in the Northern Andes

Warren B. Church, Adriana Von Hagen, 2007 – Chachapoyas: Cultural Development at an Andean Cloud Forest Crossroads

Federico Kauffmann Doig, 1988 – Ultratumba entre los Antiguos Peruanos

Robert Bradley, 2005 – The Architecture of Kuelap

Garcilaso de la Vega, 1986 – La Florida del Inca (1605)

About the author:

Creative non-fiction writer, researcher and photographer, Georges Fery addresses topics, from history, culture, and beliefs to daily living of ancient and today’s communities of the Americas. His articles are published online at travelthruhistory.com, ancient-origins.net and popular-archaeology.com, in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com), as well as in the U.K. at mexicolore.co.uk.

Georges Fery author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies instituteofmayastudies.org Miami, FL and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org. As well as member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu, and the NFAA – Non-Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthrosassociation.com.

Contact: Georges Fery – 5200 Keller Springs Road, Apt. 1511, Dallas, Texas 75248. T. (786) 501 9692 – gfery.43@gmail.com and www.georgefery.com

Image credits:

- Northern Peru by @thetrekblog.com

- Kuélap, the Citadel by @peru.travel.com

- Kuelap by Martin St-Amant (S23678), CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Western Gate by @miguelvaldivia in antiguoperu.com

- Kuelap Living Quarters and Storage by José Porras via wikipedia CC BY-SA 2.5

- Purunmatshus Regio by @Federico Kaufman Doig

- Aya-chaqui, Types D and E by @ancient-origins.net

- Purunmatshus Type.B by @antiguoperu.com

Browse Tours from Cajamarca, Peru