by Cindy-Lou Dale

Hampshire is a truly remarkable corner of the English countryside with historic towns, boasting rich cultural heritage and small picture-postcard villages. Soft hills and deep green valley’s punctuated by sheep, and deeply wooded forests populated by wild ponies. You may feel yourself transported back in time when driving along the country roads, past ancient thatched cottages and ‘olde worlde’ pubs that serve traditional ales and pub lunches. Should you decide to call at one of these quaint English country pubs, take a tip from this seasoned traveler. Don’t make jokes when visiting England. English folk are reserved and pride themselves in their steely wit, composure and restraint.

Hampshire is a truly remarkable corner of the English countryside with historic towns, boasting rich cultural heritage and small picture-postcard villages. Soft hills and deep green valley’s punctuated by sheep, and deeply wooded forests populated by wild ponies. You may feel yourself transported back in time when driving along the country roads, past ancient thatched cottages and ‘olde worlde’ pubs that serve traditional ales and pub lunches. Should you decide to call at one of these quaint English country pubs, take a tip from this seasoned traveler. Don’t make jokes when visiting England. English folk are reserved and pride themselves in their steely wit, composure and restraint.

The most famous person from Hampshire is undoubtedly the writer, Jane Austen, (Sense and Sensibility; Pride and Prejudice; Northanger Abbey). Jane was born in the small hamlet of Steventon in 1775. Twenty-six years later her father, the Reverend George Austen, moved his family to Bath and soon Jane moved to Southampton, eventually returning to her beloved Hampshire in 1809, after her brother, Edward, gave her a permanent home at Chawton. She revised and published Sense and Sensibility (1811) and Pride and Prejudice (1813), followed by Mansfield Park (1814), and Emma (1816). She died of Addison’s disease in 1817, aged only 41. Her remains have been laid to rest at Winchester Cathedral’s North Aisle of the Nave. After her death, Jane’s final two novels, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, were published. These were the first books published under her own name; all of the novels published during her lifetime were simply inscribed as being penned “By a Lady”.

The most famous person from Hampshire is undoubtedly the writer, Jane Austen, (Sense and Sensibility; Pride and Prejudice; Northanger Abbey). Jane was born in the small hamlet of Steventon in 1775. Twenty-six years later her father, the Reverend George Austen, moved his family to Bath and soon Jane moved to Southampton, eventually returning to her beloved Hampshire in 1809, after her brother, Edward, gave her a permanent home at Chawton. She revised and published Sense and Sensibility (1811) and Pride and Prejudice (1813), followed by Mansfield Park (1814), and Emma (1816). She died of Addison’s disease in 1817, aged only 41. Her remains have been laid to rest at Winchester Cathedral’s North Aisle of the Nave. After her death, Jane’s final two novels, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, were published. These were the first books published under her own name; all of the novels published during her lifetime were simply inscribed as being penned “By a Lady”.

To reach Steventon you need to pass through a tunnel beneath the Basingstoke-to-Winchester railway line, built on a high embankment. On approach you bypass the hamlet of Dummer – once the home of Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York.

Once in Steventon, hidden in a quiet spot, off a tiny country lane, you’ll find the thirteenth century Church of St. Nicholas. Turn off your car’s engine, climb out and step hundreds of years back in time, into a world of peace and silence. The rectory, home of the Austen’s, in the field beyond and to the right of the churchyard was destroyed in a fire and all that now remains is a fenced well. Wander around awhile and soak up the surroundings, let the surrounds and peaceful parish soothe you into thoughts of rural living in another time. Once you have taken in the pastoral atmosphere step into the 700-year old church where Jane Austen worshiped and listened to her father voice his memorable sermons. The church remains effectively unchanged by Victorian restoration, and is still much the same as when Jane Austen visited.

Once in Steventon, hidden in a quiet spot, off a tiny country lane, you’ll find the thirteenth century Church of St. Nicholas. Turn off your car’s engine, climb out and step hundreds of years back in time, into a world of peace and silence. The rectory, home of the Austen’s, in the field beyond and to the right of the churchyard was destroyed in a fire and all that now remains is a fenced well. Wander around awhile and soak up the surroundings, let the surrounds and peaceful parish soothe you into thoughts of rural living in another time. Once you have taken in the pastoral atmosphere step into the 700-year old church where Jane Austen worshiped and listened to her father voice his memorable sermons. The church remains effectively unchanged by Victorian restoration, and is still much the same as when Jane Austen visited.

Famous People from Hampshire:

Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York.

Charles Kingsley, author of The Water Babies.

Richard Adams the author of Watership Down.

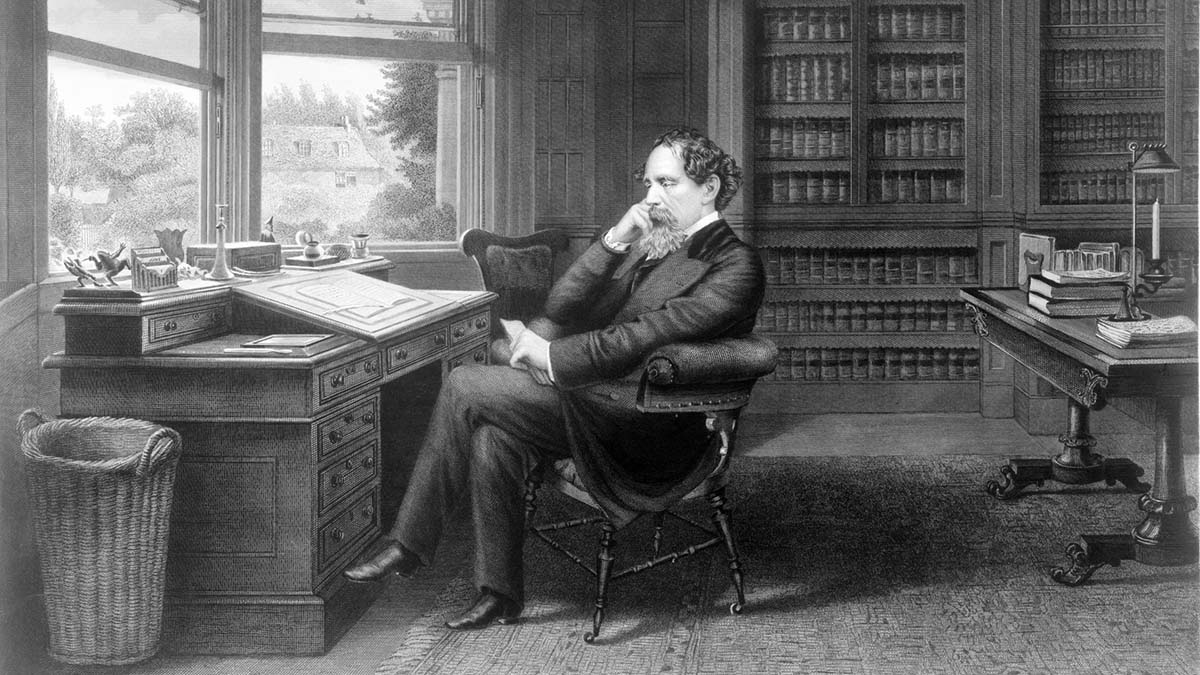

Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth.

Thomas Burberry, inventor of gabardine and maker of coats.

Composer Andrew Lloyd Weber lives in a grand manor house at Sydmonton.

Former Formula One World Champion, Jody Scheckter, lives in Laverstoke.

Actor, Jeremy Irons, was born on the Isle of Wight.

Liz Hurley, model and actress, attended college in Basingstoke.

Mark King, of pop group ‘Level 42’ fame, lives on the Isle of Wight.

Gilbert White the naturalist.

London Literary Walking Tour Of Bloomsbury

If You Go:

In the neighboring village of Chawton, is the seventeenth century Jane Austen’s museum. The beautifully kept home holds an assortment of memorabilia including Jane’s writing desk and a bureau-bookcase containing some of her first editions. The museum also boasts a peaceful eighteenth century garden containing a variety of plants and herbs common in that era. In the Old Bakehouse you will find the newly restored donkey carriage (used till this day), which Jane employed when too weak to travel on foot. The museum shop has a selection of souvenirs and a good collection of Jane Austen related books, videos (including a series shown on television), CDs and cassettes of readings.

The villages of Chawton and Alton are celebrating Jane Austen’s life and works in a range of events including music, talks, museum displays, readings, horse-drawn carriages, a ‘Fashion through the ages’ show, Victorian Cricket, and a Regency Evening in June 2008. For more information please visit the Jane Austen Regency Week website.

After enjoying Jane Austen’s museum, travel a mile or two further to the local railway station and take a trip on an authentic steam-engine across the Hampshire countryside.

For further advice and details of nearby accommodations, contact the Basingstoke Tourist Information Centre on +44 (0)1256 817618

About the author:

Cindy is an award winning writer and photojournalist whose been featured in numerous publications across the globe. She heralds from a small farming community in Southern Africa and has since lived in 18 countries. Currently her roots are in a village on the Kent coast in England.

Photo credits:

Jane Austen House Museum by R ferroni2000 / CC BY-SA

All other photos are by Cindy-Lou Dale.