by Susmita Sengupta

London can be called the city of museums, or more correctly, a city well known for offering free admissions to its museums that are home to arguably the world’s greatest collections. As a frequent visitor to this multicultural city, my family and I make it a point to visit and revisit two of the most famous museums of London, namely the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. These museums hold a treasure trove of South Asian relics and antiquities as a direct consequence of British rule over the Indian subcontinent.

In a recent visit, starting at the British Museum, we decided to bypass the heavy crowds at the Rosetta Stone, the inscribed rock discovered by Napoleon’s soldiers in Egypt, and we walked past the Elgin Marbles from the Acropolis in Greece. I decided to not get tempted by the magnificently detailed carved stone panels from Nineveh or the Assyrian stone sculptures and reliefs from 7th and 8th century BC. On most other visits, these rooms are what would attract me the most, thereby depriving me of the chance to devote time to the galleries related to objects from the Indian sub-continent.

The South Asian collection at the British Museum began with Sir Hans Sloane in the 18th century and continued on with Sir Augustus Franks who used his connections to add to the collection, most notably from Sir Alexander Cunningham, the first Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India appointed in 1871. The ASI was preceded by the Asiatic Society founded by William Jones in 1784 in Kolkata, who started a periodical journal which focused on the antiquarian wealth of India. Thus the 18th and 19th centuries proved to be a ripe period for the British to accumulate South Asian antiquities.

The crowd was sparse in the gallery when we entered compared to the other halls where the world famous artifacts are present. The South Asian objects are in Room 33 and the first thing I saw after walking in was the Mathura Lion Capital from the first century CE. Discovered in 1869 in Mathura, in central India, about 112 miles from New Delhi, the capital belongs to the Indo Scythian period (200BC – 400CE). It is covered with inscriptions in Prakrit, the predecessor of the ancient classical language Sanskrit, using Kharosthi script. The capital also shows the triratana symbol, meaning the Three Jewels, emblematic of the Buddha, his Dharma and the Sangha. This was the first of the many objects present from the rich Buddhist period of ancient Indian history. The museum has an extensive collection of Buddhist figures and reliquaries on display ranging from the ancient to the relatively modern era of 13th century India. A section of the gallery is also devoted to Buddhist objects from Thailand, Sri Lanka, Burma, Japan and China.

The crowd was sparse in the gallery when we entered compared to the other halls where the world famous artifacts are present. The South Asian objects are in Room 33 and the first thing I saw after walking in was the Mathura Lion Capital from the first century CE. Discovered in 1869 in Mathura, in central India, about 112 miles from New Delhi, the capital belongs to the Indo Scythian period (200BC – 400CE). It is covered with inscriptions in Prakrit, the predecessor of the ancient classical language Sanskrit, using Kharosthi script. The capital also shows the triratana symbol, meaning the Three Jewels, emblematic of the Buddha, his Dharma and the Sangha. This was the first of the many objects present from the rich Buddhist period of ancient Indian history. The museum has an extensive collection of Buddhist figures and reliquaries on display ranging from the ancient to the relatively modern era of 13th century India. A section of the gallery is also devoted to Buddhist objects from Thailand, Sri Lanka, Burma, Japan and China.

However, the prized possession here is certainly the remnants of the Amaravati Stupa, from the 2nd century BC. The region around Amaravati located in South India, was a major Buddhist hub during the Ashokan period. Ashoka the Great, the third Mauryan Emperor (304BC – 232BC), is well known to historians as the king who devoted himself to Buddhism after the human deaths he saw in war. His rule extended from the borders of present day Afghanistan and Iran in the west to the borders of current Bangladesh and Burma to the east. Only the southern tip of India and the country of Sri Lanka was outside his reach along with the state of Kalinga (presently the state of Orissa), located to the south of his capital Pataliputra (now called Patna). Ashoka wanted to conquer Kalinga, and where his illustrious ancestors had failed, he was hugely successful. The Kalinga War of 265BC caused a huge impact on the Emperor. Buddhist texts talk about the morning after the war when he went to review the battleground. He was struck by the carnage he encountered and became a convert to peace. The years after the Kalinga War saw a proliferation in the building of stupas, monasteries, edicts and pillars by Ashoka and he aided in the spread of Buddhism beyond India.

Similar to the Elgin Marbles of the Acropolis, the remnants of the Amaravati Stupa are sometimes known as the Elliot Marbles. I walked into the Amaravati gallery and felt myself being transported to a different, serene world. All around me were intricately sculpted discs, crossbars, slabs and railings stacked and displayed high up almost to the ceiling. I could see beautifully carved limestone discs in shapes of lotus flowers and railings and crossbars carved intricately with worshippers around an empty throne, a symbol of Buddha. There were drum slabs with gorgeous carvings of events in the life of Buddha.

The Amaravati Stupa, also known as a Maha Chaitya or Great Stupa is considered to be the largest stupa in India, even larger than its most famous counterpart, the Sanchi Stupa. While the Sanchi Stupa is a major tourist attraction in India, the Amaravati Stupa suffered a different fate. Evidence has shown that the stupa built during the reign of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, remained a major religious site well into the 14th century when Hinduism had become the primary religion in India. Till about 1344 AD, various successive dynasties, helped in building and extending the stupa and its surrounding areas.

The Amaravati Stupa, also known as a Maha Chaitya or Great Stupa is considered to be the largest stupa in India, even larger than its most famous counterpart, the Sanchi Stupa. While the Sanchi Stupa is a major tourist attraction in India, the Amaravati Stupa suffered a different fate. Evidence has shown that the stupa built during the reign of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, remained a major religious site well into the 14th century when Hinduism had become the primary religion in India. Till about 1344 AD, various successive dynasties, helped in building and extending the stupa and its surrounding areas.

After that it fell into disrepair and remained hidden till 1797 when Colonel Colin Mackenzie, a Scottish army officer in the British East India Company made its discovery. He carried out some excavations in 1816 after being appointed the first Surveyor General of India and also made detailed drawings, a folio of which survives at the British Library. Then in 1845, another Scottish officer, Sir Walter Elliot excavated more sculptures from the site and a whole collection of these were sent to the erstwhile India Museum in London. Subsequently, the sculptures were acquired by British museum after the closure of the India Museum in 1879.

The gallery also boasts of a sprawling collection of Hindu bronzes, statues and sculptures known almost misleadingly as the Bridge Collection. I admired the dark, seated stone figure of the Hindu sun god, Surya from 13th century Orissa, part of a group of eye catching sculptures which show the nine planets or the “navagrahas”. My eyes rested on a marvelously carved, seated stone figure of Ganesh, the remover of obstacles, also from the same era, depicted unusually with five heads and ten hands. The entire collection was amassed by Charles “Hindoo” Stuart, an Irish officer in the East India Company, known for his affinity to Hinduism and Indian culture. He collected antiquities mostly from the states of Bengal, Orissa, Bihar and Central India and displayed them at his home in Kolkata. After his death and burial in Kolkata in 1828, his impressive collection was transferred to England where it was sold in auction to John Bridge in 1829-30. Thus the collection was given to the museum in 1872 by the Bridge family heirs.

The gallery also boasts of a sprawling collection of Hindu bronzes, statues and sculptures known almost misleadingly as the Bridge Collection. I admired the dark, seated stone figure of the Hindu sun god, Surya from 13th century Orissa, part of a group of eye catching sculptures which show the nine planets or the “navagrahas”. My eyes rested on a marvelously carved, seated stone figure of Ganesh, the remover of obstacles, also from the same era, depicted unusually with five heads and ten hands. The entire collection was amassed by Charles “Hindoo” Stuart, an Irish officer in the East India Company, known for his affinity to Hinduism and Indian culture. He collected antiquities mostly from the states of Bengal, Orissa, Bihar and Central India and displayed them at his home in Kolkata. After his death and burial in Kolkata in 1828, his impressive collection was transferred to England where it was sold in auction to John Bridge in 1829-30. Thus the collection was given to the museum in 1872 by the Bridge family heirs.

The next day at the Victoria and Albert Museum, we entered the South Asian galleries, and found ourselves in the era of 16th-19th century India. That is not to say, the V & A does not have ancient Indian artifacts. Here too we saw the statues and relics of Buddhist periods and early Indian dynasties. But the hallmark collection here belongs to the Mughal period (1526-1748), Rajput kingdoms and the Indian rulers defeated thereafter. The spectacular collection also includes textiles, paintings, photographs and myriad objects of decorative arts from all regions of South and Southeast Asia.

The immense collection at this museum has its beginnings in the East India Company’s India Museum, founded in 1798. The V & A, which was known as the South Kensington Museum in the 1800s, received this collection in 1879 but the India Museum was formally integrated and the name abolished only in the 1950s.

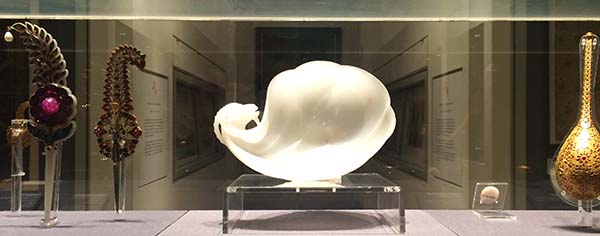

From the era of the Mughal Empire, the white nephrite jade wine cup of Emperor Shah Jahan (1592-1666), builder of the Taj Mahal, caught our attention because of its exquisite craftsmanship. Made in 1657, the cup is a unique example of artistic unity from China, India, Iran and Europe. We moved on to the Akbarnama, the chronicle of Akbar’s reign (1556-1605) by his court historian and biographer Abul Fazal. It is a collection of manuscripts painted in watercolor by royal artists with Persian inscriptions at its bottom. We looked at rooms full of outfits, furniture and everyday living objects belonging to British men and women who lived in India during the Raj. We spent our time reading everything, trying to take it all in.

From the era of the Mughal Empire, the white nephrite jade wine cup of Emperor Shah Jahan (1592-1666), builder of the Taj Mahal, caught our attention because of its exquisite craftsmanship. Made in 1657, the cup is a unique example of artistic unity from China, India, Iran and Europe. We moved on to the Akbarnama, the chronicle of Akbar’s reign (1556-1605) by his court historian and biographer Abul Fazal. It is a collection of manuscripts painted in watercolor by royal artists with Persian inscriptions at its bottom. We looked at rooms full of outfits, furniture and everyday living objects belonging to British men and women who lived in India during the Raj. We spent our time reading everything, trying to take it all in.

But we hadn’t yet seen the two most significant holdings of the museum. The first one is the solid gold throne of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the founder of the Sikh empire who ruled over undivided Punjab that stretched to the borders of Afghanistan from 1799-1839. The throne kept in the Sikh treasury came in to the possession of the British after Punjab was annexed in 1849.

Following this, we walked over to see Tipu’s Tiger. Considered by the museum to be one of its most precious and popular objects, this intriguing musical tiger mauling a red coated European soldier was made for Tipu Sultan, the king of Mysore, sometimes known as the “Tiger of Mysore” in South India. Tipu ruled from 1782 to 1799 and fought three wars against the British East India Company before being finally defeated and killed in his capital, Seringapatam in 1799. His treasury was immediately divided among the Company soldiers and the tiger was first displayed at the India museum in 1808. After the dissolution of the East India Company, this semi-automaton musical instrument was moved to the South Kensington museum, now the V & A and has been on display ever since. I realized that a visit to these two museums can be an enlightening as well as a poignant experience for most Indians.

Following this, we walked over to see Tipu’s Tiger. Considered by the museum to be one of its most precious and popular objects, this intriguing musical tiger mauling a red coated European soldier was made for Tipu Sultan, the king of Mysore, sometimes known as the “Tiger of Mysore” in South India. Tipu ruled from 1782 to 1799 and fought three wars against the British East India Company before being finally defeated and killed in his capital, Seringapatam in 1799. His treasury was immediately divided among the Company soldiers and the tiger was first displayed at the India museum in 1808. After the dissolution of the East India Company, this semi-automaton musical instrument was moved to the South Kensington museum, now the V & A and has been on display ever since. I realized that a visit to these two museums can be an enlightening as well as a poignant experience for most Indians.

Private Guided Tour of the British Museum in London

from: Viator

If You Go:

British Museum: As per the website, Room 33 is undergoing major renovation and will reopen in Nov. 2017.

Victoria and Albert Museum: Room 41 – The Nehru Gallery

Private Tour: Victoria and Albert Museum

from: Viator

About the author:

Susmita Sengupta is a freelance writer who loves to travel. She and her family have traveled to various parts of the USA, Canada, Europe, the Caribbean, Middle East, Southeast Asia and India. She resides in New York City with her family.

All photos by Susmita Sengupta:

Outside the British Museum

The Mathura Lion Capital

Carved Railing Detail from Amaravati Stupa

An Intricately Carved Sculpture of the Deity Ganesh

Emperor Shah Jahan’s Jade Wine Cup

The Gold Throne of Maharaja Ranjit Singh

The Lacquered and Carved Musical Instrument, Tipu’s Tiger

Arriving from the south, Robin Hood’s Bay is visible miles away; from a jutting limestone headland just past Ravenscar, one of a few villages on the walk. The approach to Robin Hood’s Bay at low tide is on a long stretch of sandy beach, with some rocks and pools along the way. The sea covers most of the beach at high tide; reuniting with the high cliffs in the evening like a blanket being tucked between bed and wall.

Arriving from the south, Robin Hood’s Bay is visible miles away; from a jutting limestone headland just past Ravenscar, one of a few villages on the walk. The approach to Robin Hood’s Bay at low tide is on a long stretch of sandy beach, with some rocks and pools along the way. The sea covers most of the beach at high tide; reuniting with the high cliffs in the evening like a blanket being tucked between bed and wall. The age of Robin Hood’s Bay is unknown, as it was a thriving village of fifty cottages when first recorded in 1540 by Leland, King Henry VIII’s topographer. In the following century it was recorded on Dutch sea charts, which omitted Whitby; RHB’s now much larger northern neighbour. The origins of RHB’s name are also unclear, with no recorded reference to the famous outlaw of Sherwood Forest. That legend did become popular in the 15th century though, with the first recorded ballad dated to 1450, around the same time that the Yorkshire village was thought to be growing. If Robin Hood was the John Lennon of his time, then it seems likely that people would want to name things after him. However, the local history society believe it is more likely that the name derived from ancient woodland spirits, such as Robin Goodfellow, who preceded the now more famous Medieval rebel, and may have played a part in creating the green Sherwood Forest legend, rather than Hood influencing other contemporary things.

The age of Robin Hood’s Bay is unknown, as it was a thriving village of fifty cottages when first recorded in 1540 by Leland, King Henry VIII’s topographer. In the following century it was recorded on Dutch sea charts, which omitted Whitby; RHB’s now much larger northern neighbour. The origins of RHB’s name are also unclear, with no recorded reference to the famous outlaw of Sherwood Forest. That legend did become popular in the 15th century though, with the first recorded ballad dated to 1450, around the same time that the Yorkshire village was thought to be growing. If Robin Hood was the John Lennon of his time, then it seems likely that people would want to name things after him. However, the local history society believe it is more likely that the name derived from ancient woodland spirits, such as Robin Goodfellow, who preceded the now more famous Medieval rebel, and may have played a part in creating the green Sherwood Forest legend, rather than Hood influencing other contemporary things.

The area does seem to have thrived on independence from outside control and taxes, as the legendary Robin Hood did, with the local history society writing there is no doubt that Robin Hood’s Bay was the busiest smuggling village on the Yorkshire coast by the 18th century. That coastal culture was made famous in the

The area does seem to have thrived on independence from outside control and taxes, as the legendary Robin Hood did, with the local history society writing there is no doubt that Robin Hood’s Bay was the busiest smuggling village on the Yorkshire coast by the 18th century. That coastal culture was made famous in the  Smuggling was not the only activity dividing village and rulers, as on the other side there was something that looks even more evil in history: Press Gangs were sent into villages such as Robin Hood’s Bay to find and kidnap men for the Royal Navy. Those pressed into service were unlikely to return. It is easy to imagine the drama of the 18th century in the compact steep closely-knit village that still structurally exists, with contraband passed through windows from harbour to hilltop without touching the ground; or the women banging drums when Press Gangs were spotted, and the men running to hide.

Smuggling was not the only activity dividing village and rulers, as on the other side there was something that looks even more evil in history: Press Gangs were sent into villages such as Robin Hood’s Bay to find and kidnap men for the Royal Navy. Those pressed into service were unlikely to return. It is easy to imagine the drama of the 18th century in the compact steep closely-knit village that still structurally exists, with contraband passed through windows from harbour to hilltop without touching the ground; or the women banging drums when Press Gangs were spotted, and the men running to hide. When I finished my walk from Scarborough I had to find the campsite a couple of miles farther north of the village. After stopping to take too many photos it was totally dark by then, but I was compensated by a clear night providing an amazing countryside view of the sky, after becoming used to inner city light pollution skies. Looking upwards at regular intervals for long periods of time delayed me further, but as Downhill showed, it’s not all about keeping to time, but what you see and learn along the way.

When I finished my walk from Scarborough I had to find the campsite a couple of miles farther north of the village. After stopping to take too many photos it was totally dark by then, but I was compensated by a clear night providing an amazing countryside view of the sky, after becoming used to inner city light pollution skies. Looking upwards at regular intervals for long periods of time delayed me further, but as Downhill showed, it’s not all about keeping to time, but what you see and learn along the way.

Instead, I walked back to Whitby, completing another section of the Cleveland Way. Staithes is ten miles above the town famous for Dracula’s fictional landing in England, while Robin Hood’s Bay is five miles below. As with my walk from Scarborough, I took too many photos and made slower progress than planned. Thankfully, I reached Whitby fifteen minutes before the last bus back to Leeds.

Instead, I walked back to Whitby, completing another section of the Cleveland Way. Staithes is ten miles above the town famous for Dracula’s fictional landing in England, while Robin Hood’s Bay is five miles below. As with my walk from Scarborough, I took too many photos and made slower progress than planned. Thankfully, I reached Whitby fifteen minutes before the last bus back to Leeds.

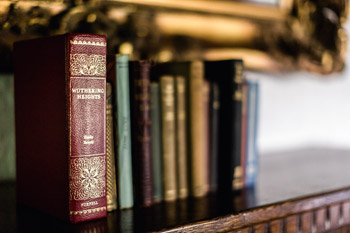

If you love Wuthering Heights devoutly, the words “bed and breakfast” can inspire fear. Would the broad beamed ceilings and mossy walls be protected, or would they be swallowed up into an upscale conversion? Bronte’s “Thrushcross Grange”, or as it is known in reality, Ponden Hall, is exactly as its hero and heroine would have it.

If you love Wuthering Heights devoutly, the words “bed and breakfast” can inspire fear. Would the broad beamed ceilings and mossy walls be protected, or would they be swallowed up into an upscale conversion? Bronte’s “Thrushcross Grange”, or as it is known in reality, Ponden Hall, is exactly as its hero and heroine would have it. “Don’t worry, I’ll take your bags,” he said as he stepped out the front door. I ushered my daughter into the long, narrow hallway lined with wellies and jackets. It is still a family home. We entered the sitting room to the right and met the home’s other half- Julie Akhurst, a warm and inviting hostess bearing tea and cookies.

“Don’t worry, I’ll take your bags,” he said as he stepped out the front door. I ushered my daughter into the long, narrow hallway lined with wellies and jackets. It is still a family home. We entered the sitting room to the right and met the home’s other half- Julie Akhurst, a warm and inviting hostess bearing tea and cookies. We were upgraded you to the Heaton Room, the first of many kindnesses Our room was as if a home of its own. Two twin beds were at opposite ends of the room while a large four-poster graced the interior wall. Stephen had built a warm fire in the hearth in front of the chairs and sofa, and the ceiling reached up to a height that made the room grander than a suite. It was quiet enough to hear the cows chewing the grass outside our window, and when we went to bed, a slight wind rattled the windows occasionally, but seemed to promise calm.

We were upgraded you to the Heaton Room, the first of many kindnesses Our room was as if a home of its own. Two twin beds were at opposite ends of the room while a large four-poster graced the interior wall. Stephen had built a warm fire in the hearth in front of the chairs and sofa, and the ceiling reached up to a height that made the room grander than a suite. It was quiet enough to hear the cows chewing the grass outside our window, and when we went to bed, a slight wind rattled the windows occasionally, but seemed to promise calm. Despite the protective comfort of our warm duvets, we eagerly came down for traditional British breakfast. The Akhurst-Brown family invited us to join them at dinner because it would be late for us to take a taxi to the local pub the previous night and Julie proved she is an excellent cook with a delicious squash soup. Julie came in and out of the kitchen juices, fresh eggs, and warm homemade bread. Stephen pulled two large pillows in front of the stone fireplace so my daughter could sprawl out on the stone floors and watch cartoons. Listening to the family move behind us in the daily lives added more warmth to the room, aside from their heated stone floors and their giant Aga stove, than I ever could have imagined. Indeed it felt as if the haunted souls of Wuthering Heights had been set free.

Despite the protective comfort of our warm duvets, we eagerly came down for traditional British breakfast. The Akhurst-Brown family invited us to join them at dinner because it would be late for us to take a taxi to the local pub the previous night and Julie proved she is an excellent cook with a delicious squash soup. Julie came in and out of the kitchen juices, fresh eggs, and warm homemade bread. Stephen pulled two large pillows in front of the stone fireplace so my daughter could sprawl out on the stone floors and watch cartoons. Listening to the family move behind us in the daily lives added more warmth to the room, aside from their heated stone floors and their giant Aga stove, than I ever could have imagined. Indeed it felt as if the haunted souls of Wuthering Heights had been set free.

A splendid view of the Wall is seen at Housesteads in Northumberland at a section between Walltown Crags where it undulates for several miles over Whin Still ridge. I loved to ramble on top of the Wall itself where it is eight to ten feet wide and over ten feet high. I would stand alone on one of the Wall’s highest vantage points and look down on some of the most spectacular scenery in England, and immerse myself with thoughts of Roman legions patrolling where my own feet were firmly planted. I could envision them toiling to pull earth, cut turf, and lay stones, hewed, hacked and sawed and placed one by one to strengthen and form this massive barrier their Emperor had ordered.

A splendid view of the Wall is seen at Housesteads in Northumberland at a section between Walltown Crags where it undulates for several miles over Whin Still ridge. I loved to ramble on top of the Wall itself where it is eight to ten feet wide and over ten feet high. I would stand alone on one of the Wall’s highest vantage points and look down on some of the most spectacular scenery in England, and immerse myself with thoughts of Roman legions patrolling where my own feet were firmly planted. I could envision them toiling to pull earth, cut turf, and lay stones, hewed, hacked and sawed and placed one by one to strengthen and form this massive barrier their Emperor had ordered.

Few facilities existed then and I continued my trudge over undulating hills, past a tiny wood and down a small valley, dotted with grass chewing sheep with the occasional osprey swooping down to grab an unsuspecting field mouse, to the hamlet of Once Brewed where The Twice Brewed Inn served good hearty northern fare. Feet sore, body aching, a hot home cooked meal washed down with a local light ale, and I was in my heaven on earth and I have never found anywhere better. Forgotten was children’s writer Beatrix Potter’s Cumbrian house, Hill Top, where she created her characters Peter Rabbit and Jemima Puddle Duck. It would be seen another day. William Wordsworth, inspired by the same lakes and mountains, could also be remembered another time, and Dove Cottage on Lake Grasmere, where he lived for over fifty years, could be re-visited. But, during my allotted time with Hadrian and his Wall, I had deliberately stayed remote with my thoughts midst Nature’s grandeur and Rome’s remnants from empire building, aware that, just around a corner in a lane in Once Brewed, I had left a car which would transport me down the road back into Yorkshire and family happenings, where tranquility, dreams and contemplation would be put on hold.

Few facilities existed then and I continued my trudge over undulating hills, past a tiny wood and down a small valley, dotted with grass chewing sheep with the occasional osprey swooping down to grab an unsuspecting field mouse, to the hamlet of Once Brewed where The Twice Brewed Inn served good hearty northern fare. Feet sore, body aching, a hot home cooked meal washed down with a local light ale, and I was in my heaven on earth and I have never found anywhere better. Forgotten was children’s writer Beatrix Potter’s Cumbrian house, Hill Top, where she created her characters Peter Rabbit and Jemima Puddle Duck. It would be seen another day. William Wordsworth, inspired by the same lakes and mountains, could also be remembered another time, and Dove Cottage on Lake Grasmere, where he lived for over fifty years, could be re-visited. But, during my allotted time with Hadrian and his Wall, I had deliberately stayed remote with my thoughts midst Nature’s grandeur and Rome’s remnants from empire building, aware that, just around a corner in a lane in Once Brewed, I had left a car which would transport me down the road back into Yorkshire and family happenings, where tranquility, dreams and contemplation would be put on hold.

Brighton’s train station is still magnificently Victorian, with its soaring iron roof. The formerly sleepy fishing village of Brighthelmstone began to be transformed towards the end of the eighteenth century when the aristocracy arrived ‘to take the waters’, but it wasn’t until the arrival of the railway in the 1840s, that Brighton really put itself on the map and became the destination of choice for toffs and day-trippers alike.

Brighton’s train station is still magnificently Victorian, with its soaring iron roof. The formerly sleepy fishing village of Brighthelmstone began to be transformed towards the end of the eighteenth century when the aristocracy arrived ‘to take the waters’, but it wasn’t until the arrival of the railway in the 1840s, that Brighton really put itself on the map and became the destination of choice for toffs and day-trippers alike. I took a walk along the sea-front, breathing deeply of the sea air, and made a nostalgic detour to the pier, complete with funfair and fish and chips. I visited the small but perfectly-formed Fishing Museum. The fishermen of Brighthelmstone were not best pleased at the arrival of all these new visitors, but they made the best of it.

I took a walk along the sea-front, breathing deeply of the sea air, and made a nostalgic detour to the pier, complete with funfair and fish and chips. I visited the small but perfectly-formed Fishing Museum. The fishermen of Brighthelmstone were not best pleased at the arrival of all these new visitors, but they made the best of it. When it came to mistresses and houses, the Prince Regent was a lover of excess. ‘The more, the merrier’ would appear to be his motto. His mistresses were plump and matronly, and his houses extravagant.

When it came to mistresses and houses, the Prince Regent was a lover of excess. ‘The more, the merrier’ would appear to be his motto. His mistresses were plump and matronly, and his houses extravagant.