by Johnny Caito

In addition to the chestnut lined beer gardens that fill Munich’s city center, there is a history which runs so deep that one can nearly taste the metallic remnants of 70-year-old bombs. Upon mention of Munich, Germany, the image usually conjured up in the minds of travelers is full liter beer steins, lederhosen, and pumping brass bands under a giant canopy tent. However, those who dare to look deeper into the city will find traces of one of the darkest times in the history of the planet and a city so fascinating, that even the biggest history buff’s heads will spin.

Instead of carrying around a thick guide book which forces visitors to stare down at the tiny print and flip pages, a great option for those seeking to learn about the war-related history is to sign up for Sandeman’s New Europe, Third Reich walking tour. For 12 euro, my journey through the dark history began at the center of the city, at the beautiful Marienplatz. Immediately, the tour guide, who was a walking treasure chest of knowledge instructed the group of 10-15 people to look up at our surroundings. After explaining how the majority of the area was completely bombed out during World War II, he pointed to the main spires of the Marienplatz, and the giant green domes from the Frauenkirche. He explained how the bomber jets from the allied forces used them as landmarks in their bombing campaign, therefore they were spared and remained mostly intact. Chills immediately shot down my spine, as I felt the realness in which surrounded me. This was real, and these were not events which took place in the Dark Ages; this was a time that our close relatives could have lived through. It was a time in which the desperation of the German people gave way to the rise of a former painter from Austria, and allowed Adolf Hitler to guide his people, and the world into a conflict that took the lives of nearly 85 million people.

Instead of carrying around a thick guide book which forces visitors to stare down at the tiny print and flip pages, a great option for those seeking to learn about the war-related history is to sign up for Sandeman’s New Europe, Third Reich walking tour. For 12 euro, my journey through the dark history began at the center of the city, at the beautiful Marienplatz. Immediately, the tour guide, who was a walking treasure chest of knowledge instructed the group of 10-15 people to look up at our surroundings. After explaining how the majority of the area was completely bombed out during World War II, he pointed to the main spires of the Marienplatz, and the giant green domes from the Frauenkirche. He explained how the bomber jets from the allied forces used them as landmarks in their bombing campaign, therefore they were spared and remained mostly intact. Chills immediately shot down my spine, as I felt the realness in which surrounded me. This was real, and these were not events which took place in the Dark Ages; this was a time that our close relatives could have lived through. It was a time in which the desperation of the German people gave way to the rise of a former painter from Austria, and allowed Adolf Hitler to guide his people, and the world into a conflict that took the lives of nearly 85 million people.

Walking through the streets of the 1,000-year-old city would lead most to believe that the surrounding buildings go back hundreds of years, but they would be greatly mistaken. Following the rise of Adolf Hitler in the early 1930s, Munich became the birthplace of the Nazi Party, and eventually one of the biggest targets for the allies during World War II. The result was thousands of bombs being droppedtact on the city, and to this day, an estimated 2,000 un-detonated bombs are still buried beneath the city. Since nearly 90 percent of the city was completely demolished, everything has been rebuilt, and reconstructed in the 70 years since to end of the war. While construction continues in the Bavarian capital, bombs are still discovered on a weekly basis, and teams have to come in to safely detonate the bombs which range anywhere from 4 lbs to 22,000 lbs. Our tour guide told stories how entire street blocks have to be closed, and entire apartment complexes cleared out when one is discovered. Life goes on, and the residents of Munich accept it as if it is nothing more than a minor inconvenience.

Walking through the streets of the 1,000-year-old city would lead most to believe that the surrounding buildings go back hundreds of years, but they would be greatly mistaken. Following the rise of Adolf Hitler in the early 1930s, Munich became the birthplace of the Nazi Party, and eventually one of the biggest targets for the allies during World War II. The result was thousands of bombs being droppedtact on the city, and to this day, an estimated 2,000 un-detonated bombs are still buried beneath the city. Since nearly 90 percent of the city was completely demolished, everything has been rebuilt, and reconstructed in the 70 years since to end of the war. While construction continues in the Bavarian capital, bombs are still discovered on a weekly basis, and teams have to come in to safely detonate the bombs which range anywhere from 4 lbs to 22,000 lbs. Our tour guide told stories how entire street blocks have to be closed, and entire apartment complexes cleared out when one is discovered. Life goes on, and the residents of Munich accept it as if it is nothing more than a minor inconvenience.

Prior to the air-raids by allied troops, Adolf Hitler was well aware that Munich would be a major target, and knew the city would be leveled. Planning ahead, he ordered photos be taken throughout the city, so that when the war ended, the city could be built exactly as it was prior to its near destruction. Following the death of Hitler and the fall of the Nazi’s, the German people voted to restore the city to its old glory, resulting in a complete rebuild. Since everything has been rebuilt, it gives visitors a unique perspective roaming the streets, and ducking into beer halls and cafes that fill the city. While the history is thick, and I could nearly feel it hanging in the air, it also felt like stepping into a movie set. Along the guided tour, we were taken to places of historical significance, such as the world-famous Hofbräuhaus. We were taken upstairs into the beautiful beer hall, and shown the place where the Nazi leader once spoke. However, the reality is that the building is a complete replication of the original, somewhat taking away some of the powerfulness which stood before me. It is fascinating, yet saddening how such beautiful architecture and sights were destroyed, but in spite of the restoration, there is still the ghost of the German dictator that echoes throughout the halls.

Prior to the air-raids by allied troops, Adolf Hitler was well aware that Munich would be a major target, and knew the city would be leveled. Planning ahead, he ordered photos be taken throughout the city, so that when the war ended, the city could be built exactly as it was prior to its near destruction. Following the death of Hitler and the fall of the Nazi’s, the German people voted to restore the city to its old glory, resulting in a complete rebuild. Since everything has been rebuilt, it gives visitors a unique perspective roaming the streets, and ducking into beer halls and cafes that fill the city. While the history is thick, and I could nearly feel it hanging in the air, it also felt like stepping into a movie set. Along the guided tour, we were taken to places of historical significance, such as the world-famous Hofbräuhaus. We were taken upstairs into the beautiful beer hall, and shown the place where the Nazi leader once spoke. However, the reality is that the building is a complete replication of the original, somewhat taking away some of the powerfulness which stood before me. It is fascinating, yet saddening how such beautiful architecture and sights were destroyed, but in spite of the restoration, there is still the ghost of the German dictator that echoes throughout the halls.

A trip to Munich to soak up some suds is well worth the trip, but visitors who fail to look into the deep, dark part of history would be cheating themselves. The city is filled with beautiful sights, friendly people, amazing food and beer, but taking a step back to explore the underground of the Bavarian capital is a must for anyone visiting. George Santayana once said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” and there’s no place where this statement holds more truth than it does in Munich, Germany.

If You Go:

♦ Sandeman’s New Europe Walking Tours: Other paid tours include: Dachau, Beer Challenge, Neuschwanstein, and a free walking tour around the city center. www.newmunichtours.com/daily-tours/third-reich.html

♦ The city is incredibly safe, so do not be afraid to explore a lot of it on foot.

♦ Use public transportation. S-Bahn and U-Bahn is very inexpensive and will take you anywhere you want to go in the city.

♦ Bavarian people are very friendly, but learning a couple of words will help make the experience even more enjoyable.

About the author:

Johnny Caito is a writer, travel, and craft beer fan from San Diego, California. When traveling, he finds nothing more exhilarating than meeting locals who can help him explore the areas beyond the guide books, and give him a glimpse into their world.

All photos by Johnny Caito.

Mainz history goes back to when the Romans built a fort here around the 1st century BC. The name “Mainz” may have derived from the Roman name for the river, Main. But until the 20th century it was referred to in English as Mayence. Besides this temple there are other ruins nearby including the site of the original Roman citadel where there is a cenotaph raised by legionaries to commemorate their hero Drusus. Among the sites are the ruins of an aqueduct and theatre. Some of the artifacts of Roman times can be viewed in the Museum of Antike Schiffahrt and Mainz most important museum, the Landesmuseum.

Mainz history goes back to when the Romans built a fort here around the 1st century BC. The name “Mainz” may have derived from the Roman name for the river, Main. But until the 20th century it was referred to in English as Mayence. Besides this temple there are other ruins nearby including the site of the original Roman citadel where there is a cenotaph raised by legionaries to commemorate their hero Drusus. Among the sites are the ruins of an aqueduct and theatre. Some of the artifacts of Roman times can be viewed in the Museum of Antike Schiffahrt and Mainz most important museum, the Landesmuseum.

Mainz is home to a Carnival, the Mainzer Fassenacht, originating in the 19th century. We walked around the carnival square where there’s a statue of Friedrich von Schiller, a 19th century writer and poet for whom the Square is named. The Carnival is held on Rosenmontag (Rose Monday), before Ash Wednesday and is one of the city’s biggest celebrations.

Mainz is home to a Carnival, the Mainzer Fassenacht, originating in the 19th century. We walked around the carnival square where there’s a statue of Friedrich von Schiller, a 19th century writer and poet for whom the Square is named. The Carnival is held on Rosenmontag (Rose Monday), before Ash Wednesday and is one of the city’s biggest celebrations. The immense Cathedral of Saint Martin is nearly 1000 years old, built in Romanesque style. It has six individual pipe organs inside all accessed from one large console. The Augustine Church with its magnificent Baroque facade was built originally as a hermit’s monastery in the mid l700’s and is now a seminary church noted for its beautiful interior with ceiling frescoes that provide insights into the life of St Augustine. The Catholic Church of St. Peter is one of the most important Baroque building in the city. Originally a monastery, the present church was built between 1740 and 1756 by architect Johann Valentin Thoman. Inside you’ll see amazing Baroque altars and ceiling frescoes. Christuskirche is an evangelical church in an Italian High Renaissance style. It serves as a music venue as well as church. The old Gothic Church of St. Christoph dates to the 9th century. It contains an original 15th century baptismal font. Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the first printing press was baptized here.

The immense Cathedral of Saint Martin is nearly 1000 years old, built in Romanesque style. It has six individual pipe organs inside all accessed from one large console. The Augustine Church with its magnificent Baroque facade was built originally as a hermit’s monastery in the mid l700’s and is now a seminary church noted for its beautiful interior with ceiling frescoes that provide insights into the life of St Augustine. The Catholic Church of St. Peter is one of the most important Baroque building in the city. Originally a monastery, the present church was built between 1740 and 1756 by architect Johann Valentin Thoman. Inside you’ll see amazing Baroque altars and ceiling frescoes. Christuskirche is an evangelical church in an Italian High Renaissance style. It serves as a music venue as well as church. The old Gothic Church of St. Christoph dates to the 9th century. It contains an original 15th century baptismal font. Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the first printing press was baptized here. There are several interesting day-trips out of Mainz. The region is rich in variety with idyllic river scenery, historical towns and picturesque villages. The Rhineland-Palatinate is famous as a wine region and the romantic castles along the river and was named by UNESCO as one of the most beautiful landscapes and world heritage sites.

There are several interesting day-trips out of Mainz. The region is rich in variety with idyllic river scenery, historical towns and picturesque villages. The Rhineland-Palatinate is famous as a wine region and the romantic castles along the river and was named by UNESCO as one of the most beautiful landscapes and world heritage sites.

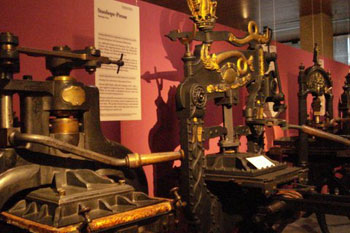

A German goldsmith, printer and publisher, Johannes Gutenberg invented the mechanical moveable type printing press and this invention started the Printing Revolution. His first major work was the Gutenberg Bible (known as the 42-line Bible). 180 of them were printed on paper and vellum, though only 21 copies survive, two of them may be seen in the museum. There is also a replica of Gutenberg’s printing press, rebuilt according to woodcuts from the 15th and 16th century.

A German goldsmith, printer and publisher, Johannes Gutenberg invented the mechanical moveable type printing press and this invention started the Printing Revolution. His first major work was the Gutenberg Bible (known as the 42-line Bible). 180 of them were printed on paper and vellum, though only 21 copies survive, two of them may be seen in the museum. There is also a replica of Gutenberg’s printing press, rebuilt according to woodcuts from the 15th and 16th century.

This museum is a must-see for anyone interested in books and printing. The Gutenberg Museum displays two copies of the Bible and Shuelburgh Bible as well as other publications representing the history of the printed word. Here you may see the very earliest typesetting machines and books that were published centuries after the Gutenberg Bible. There is also a small library open to the public that contains a collection of books from the 17th to the 20th centuries.

This museum is a must-see for anyone interested in books and printing. The Gutenberg Museum displays two copies of the Bible and Shuelburgh Bible as well as other publications representing the history of the printed word. Here you may see the very earliest typesetting machines and books that were published centuries after the Gutenberg Bible. There is also a small library open to the public that contains a collection of books from the 17th to the 20th centuries.

On March 20th, 1933, Heinrich Himmler and the temporary chief of police in Munich announced that a concentration camp had been built in small town of Dachau in Germany to imprison anyone who “opposed’ the Nazi political party.

On March 20th, 1933, Heinrich Himmler and the temporary chief of police in Munich announced that a concentration camp had been built in small town of Dachau in Germany to imprison anyone who “opposed’ the Nazi political party. The prisoners attended roll call twice a day. During this time they were forced to line up in front of the barracks and stand motionless for an hour as the camp officers would count each prisoner. If anyone had died during the night, the corpse would then be dragged to the roll call area in front of all the other prisoners to be counted. If one of the prisoners had attempted to escape during the night, all of the other inmates were forced to stand at attention for hours on end, regardless of whether the attempt was successful or not. The officers would often torture or punish the prisoner for the others to witness. Sometimes the sick and dying inmates would collapse during roll call, and if any of the fellow inmates dared to help them, they would be punished. Punishment became an hourly occurrence inside Dachau. Prisoners were punished by food withdrawal, mail bans, or at worst, the infamous pole-hanging. Inmates were forced to work throughout the entire day and well into the evening, and were only given a limited amount of time to sleep during the night. They were also forced to put on heavy winter coats while they worked outside during the summer months, or even stand naked while they worked in the cold. If a prisoner was declared “unfit for work,” they would then be transported to the Hartheim Castle, (which was about 17 kilometers away from Linz in Germany); never to be seen or heard from again.

The prisoners attended roll call twice a day. During this time they were forced to line up in front of the barracks and stand motionless for an hour as the camp officers would count each prisoner. If anyone had died during the night, the corpse would then be dragged to the roll call area in front of all the other prisoners to be counted. If one of the prisoners had attempted to escape during the night, all of the other inmates were forced to stand at attention for hours on end, regardless of whether the attempt was successful or not. The officers would often torture or punish the prisoner for the others to witness. Sometimes the sick and dying inmates would collapse during roll call, and if any of the fellow inmates dared to help them, they would be punished. Punishment became an hourly occurrence inside Dachau. Prisoners were punished by food withdrawal, mail bans, or at worst, the infamous pole-hanging. Inmates were forced to work throughout the entire day and well into the evening, and were only given a limited amount of time to sleep during the night. They were also forced to put on heavy winter coats while they worked outside during the summer months, or even stand naked while they worked in the cold. If a prisoner was declared “unfit for work,” they would then be transported to the Hartheim Castle, (which was about 17 kilometers away from Linz in Germany); never to be seen or heard from again. The barracks were used as day rooms and dormitories for the prisoners, and although each barrack was designed to hold 200 prisoners, by the end of World War II in 1945, up to 2,000 prisoners were packed into these small living quarters. (The Jewish prisoners slept in barrack #15 which was separated from the rest of the camp with barbed wire).

The barracks were used as day rooms and dormitories for the prisoners, and although each barrack was designed to hold 200 prisoners, by the end of World War II in 1945, up to 2,000 prisoners were packed into these small living quarters. (The Jewish prisoners slept in barrack #15 which was separated from the rest of the camp with barbed wire). Dachau’s crematorium was built in 1940 in order to deal with the increasing number of deaths at the camp, followed by a larger crematorium as well as a gas chamber at the end of 1942. It was inside this gas chamber where the mass murders at Dachau occurred. Fake shower sprouts were installed in the ceiling in order to fool the prisoners into thinking they were going to take a shower. Within a period of 15 to 20 minutes, approximately 150 victims would have been poisoned to death inside the gas chamber. A separate room in the crematorium area known as the “death chamber” used to store the corpses that were brought in from the camp. These corpses were then cremated in one of the stoves, and it is said that each of the stoves could cremate two to three bodies at the same time.

Dachau’s crematorium was built in 1940 in order to deal with the increasing number of deaths at the camp, followed by a larger crematorium as well as a gas chamber at the end of 1942. It was inside this gas chamber where the mass murders at Dachau occurred. Fake shower sprouts were installed in the ceiling in order to fool the prisoners into thinking they were going to take a shower. Within a period of 15 to 20 minutes, approximately 150 victims would have been poisoned to death inside the gas chamber. A separate room in the crematorium area known as the “death chamber” used to store the corpses that were brought in from the camp. These corpses were then cremated in one of the stoves, and it is said that each of the stoves could cremate two to three bodies at the same time. Unfortunately by the time American soldiers discovered Dachau on April 29th, 1945, it was already too late for many of the victims.

Unfortunately by the time American soldiers discovered Dachau on April 29th, 1945, it was already too late for many of the victims.

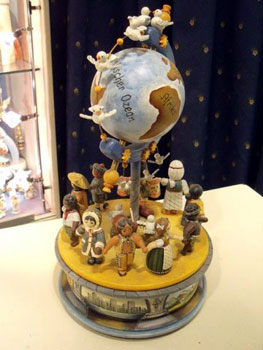

How did the largest chain of stores in the world selling traditional German Christmas items come to fruition? You can thank the military police as the reason. Circa 1963, IBM worker Wilhelm Wohlfahrt went door to door around the military installation in Boblingen trying to sell some music boxes made in Erzgebirge (in Saxony). He had only wanted to buy one originally for his friends, but was forced to buy a lot of ten from a wholesaler, so he wanted to unload the rest to recoup his money. He was found out and foiled by the military police since this activity was illegal. They suggested to him that he sell them at weekend craft shows on base instead, and the rest is history.

How did the largest chain of stores in the world selling traditional German Christmas items come to fruition? You can thank the military police as the reason. Circa 1963, IBM worker Wilhelm Wohlfahrt went door to door around the military installation in Boblingen trying to sell some music boxes made in Erzgebirge (in Saxony). He had only wanted to buy one originally for his friends, but was forced to buy a lot of ten from a wholesaler, so he wanted to unload the rest to recoup his money. He was found out and foiled by the military police since this activity was illegal. They suggested to him that he sell them at weekend craft shows on base instead, and the rest is history. Nuremberg is known for its dockenmacher (dollmakers) dating back to medieval times. Because a nice dollhouse is often on the Christmas wish list of many children. I found the most comprehensive collection of doll houses, dolls, and doll house fixtures at the Spielzeugmusuem. It will astonish you. The older the dolls and their related items, the more detailed they seemed to be. It’s amazing just how much effort the past generations have put into creating such detailed toys, an art that seems to have been generally lost because of the hyper-technological age we live in today. But this is just the tip of the iceberg of what toys you’ll see there, toys that brought back a lot of childhood memories for me.

Nuremberg is known for its dockenmacher (dollmakers) dating back to medieval times. Because a nice dollhouse is often on the Christmas wish list of many children. I found the most comprehensive collection of doll houses, dolls, and doll house fixtures at the Spielzeugmusuem. It will astonish you. The older the dolls and their related items, the more detailed they seemed to be. It’s amazing just how much effort the past generations have put into creating such detailed toys, an art that seems to have been generally lost because of the hyper-technological age we live in today. But this is just the tip of the iceberg of what toys you’ll see there, toys that brought back a lot of childhood memories for me. Nuremberg gingerbread (known as lebkuchen) is considered some of the best in the world. Lebkuchen has its roots via the Franconian monks who created honey cakes (pfefferkuchen), of which the sweet nectar was procured from the local bee colonies since it was cheaper to use than imported Asian sugar. But the lebkuchen that we know today goes back around six centuries to 1395, though the first city gingerbread guild didn’t come out until 1643. A law was made requiring sellers to own their own oven and a number of bakers became masters by marrying the daughter of a master baker.

Nuremberg gingerbread (known as lebkuchen) is considered some of the best in the world. Lebkuchen has its roots via the Franconian monks who created honey cakes (pfefferkuchen), of which the sweet nectar was procured from the local bee colonies since it was cheaper to use than imported Asian sugar. But the lebkuchen that we know today goes back around six centuries to 1395, though the first city gingerbread guild didn’t come out until 1643. A law was made requiring sellers to own their own oven and a number of bakers became masters by marrying the daughter of a master baker. The Neefs use such ingredients like ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon, hazelnuts, vanilla, cloves, honey, lemon peel and orange peel for their base recipe that’s over 500 years old, though they offer 8 kinds during the fall and winter (including one with chocolate). The bakery uses machinery that can produce 2500 mound-like lebkuchen in an hour (compared to individual hand molds that a skilled baker would take 5 hours to shape that same amount by scraping the batter like a brick layer does mortar for bricklaying). I was able to sample some of the raw dough that was dominated by the flavor of orange. It takes 15 minutes at 356 degrees Fahrenheit (180 degrees Centigrade) to bake the lebkuchen, and upon coming out of the oven, it’s a must try, even if you’re on a diet! What I like about the finished goodies is the lightly fruity flavor that’s got a chewy feel to it. The ones with chocolate were especially good.

The Neefs use such ingredients like ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon, hazelnuts, vanilla, cloves, honey, lemon peel and orange peel for their base recipe that’s over 500 years old, though they offer 8 kinds during the fall and winter (including one with chocolate). The bakery uses machinery that can produce 2500 mound-like lebkuchen in an hour (compared to individual hand molds that a skilled baker would take 5 hours to shape that same amount by scraping the batter like a brick layer does mortar for bricklaying). I was able to sample some of the raw dough that was dominated by the flavor of orange. It takes 15 minutes at 356 degrees Fahrenheit (180 degrees Centigrade) to bake the lebkuchen, and upon coming out of the oven, it’s a must try, even if you’re on a diet! What I like about the finished goodies is the lightly fruity flavor that’s got a chewy feel to it. The ones with chocolate were especially good.