by W. Ruth Kozak

by W. Ruth Kozak

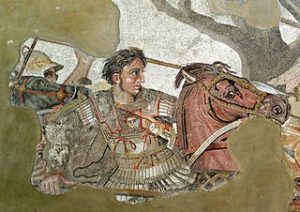

By the harbour in Thessaloniki, Greece, stands a magnificent statue of the young warrior-king, Alexander the Great, astride his fabled horse Bucephalus. At the base of the monument someone has laid two wreaths: myrtle for a hero, laurel for a god. It is June 10, the anniversary of Alexander’s death. I place a simple bouquet of red carnations beside the wreaths. Just who was this ambitious, brilliant young man? Alexander was only 20 when he became king of Macedonia and 22 when he set out to conquer the world. By the time he died suddenly and suspiciously in Babylon just 10 years later in 323 BC, he ruled an empire that included Persia and Egypt and stretched to India.

I first became acquainted with Alexander when I was in my teens and he has become part of my life. I have realized a dream, coming to northern Greece to trace his footsteps. My search for Alexander began in Athens when I boarded a bus heading north. The bus route follows the coast, skirting the teal-blue sea, past olive groves and fertile fields. As the bus nears the Thessaly/Macedonian border, Mount Olympus looms into sight. It is Greece’s highest and most awe-inspiring mountain. The ancients believed it to be the home of the twelve gods, the Olympians. Nestled under its towering northern flank lies ancient Dion, a sacred city of the Macedonians. Alexander visited here to make his oblations to the gods before setting off to conquer the world.

In Alexander’s time, northern Greece was populated by many tribes, one of which was the Makedonoi. When his father, Philip II, became king, the balance of power in the Hellenic world fell into the hands of Macedonia. Under his command, Philip formed the League of Corinth and within a few years he had conquered all the outlying tribes. To ensure their allegiance, Philip arranged marriages with daughters of clan chieftains. One of these political unions brought him to the island of Samothraki in Thrace. And this is where Alexander’s story begins.

At Thessaloniki, named for one of Alexander’s half-sisters, I board a bus heading across Macedonia to Thrace. East of Thessaloniki, the coastline is rugged with low mountains rolling down to the rocky sea coast. Alexandroupolis, a pleasant city near the Turkish frontier, originated as a small Thracian garrison town founded by Alexander. Offshore, the island of Samothraki rises mysteriously out of the sea. It was on this island that Philip met his bridge, the bewitching Epirote princess, Olympias. They soon wed and became the parents of a remarkable son, Alexander.

At Thessaloniki, named for one of Alexander’s half-sisters, I board a bus heading across Macedonia to Thrace. East of Thessaloniki, the coastline is rugged with low mountains rolling down to the rocky sea coast. Alexandroupolis, a pleasant city near the Turkish frontier, originated as a small Thracian garrison town founded by Alexander. Offshore, the island of Samothraki rises mysteriously out of the sea. It was on this island that Philip met his bridge, the bewitching Epirote princess, Olympias. They soon wed and became the parents of a remarkable son, Alexander.

From Alexandroupolis I boarded the two-hour ferry trip to Samothraki. Once there, I walked the five kilometres through the lush countryside to the sanctuary of the Great Gods. The magnificent marble pillars of the temple loom ahead of me in a grove of trees. At the time of Philip’s marriage to Olympias, this sanctuary was the centre of religious life in northern Greece.

I place my hands on the magnetic lodestone of Samothraki, which represents the Great Mother. The russet-coloured stone burns beneath my touch. Supplicants used to hang iron votives here. Every member of the Macedonian royalty was initiated into the cult of the Great Mother. At one time, Alexander must have stood in this very place. Nearby I find the ruins of a small building erected in 318 BC, dedicated to Alexander and his father Philip by their sons, the join-kings, Philip Arridaios and Alexander IV.

I place my hands on the magnetic lodestone of Samothraki, which represents the Great Mother. The russet-coloured stone burns beneath my touch. Supplicants used to hang iron votives here. Every member of the Macedonian royalty was initiated into the cult of the Great Mother. At one time, Alexander must have stood in this very place. Nearby I find the ruins of a small building erected in 318 BC, dedicated to Alexander and his father Philip by their sons, the join-kings, Philip Arridaios and Alexander IV.

From the tranquility of Samothraki, I return to Thessaloniki. From there, it’s a short bus ride to Pella, the ancient capital of Macedonia, Alexander’s birthplace. Several private villas have been excavated there and there are traces of wide streets flanked by foot-paths and a central avenue crossing the Agora.

The palace where Alexander was born in 365 BC is located on a rise behind the city. Known as the “wonder of the north” it was a significant example of Greek palatial architecture. The palace site is closed because of on-going excavations, but in the small museum across the highway from the site, there is a reconstruction of it and the villas. Exhibits include a pebble mosaic depicting Alexander and a friend hunting lions, and a bust of Alexander in his youth.

Greek poets, tragedians, historians, philosophers, doctors, actors, painters and craftsmen were invited to the Macedonian court. One of these philosophers was Aristotle whom Philip invited to tutor his son at school he had build known as the Nymphaeion” at Mieza, near modern Naoussa. The school, called “The Peripatos” (“walk”) was a two storey L-shaped building linked by staircases, built along the face of the rock. The school’s facilities were set up to harmonize and blend in with the environment, incorporating several caves. Here, in this tranquil setting of lush vegetation, fresh water springs and caves, Aristotle taught Alexander his companions.

Greek poets, tragedians, historians, philosophers, doctors, actors, painters and craftsmen were invited to the Macedonian court. One of these philosophers was Aristotle whom Philip invited to tutor his son at school he had build known as the Nymphaeion” at Mieza, near modern Naoussa. The school, called “The Peripatos” (“walk”) was a two storey L-shaped building linked by staircases, built along the face of the rock. The school’s facilities were set up to harmonize and blend in with the environment, incorporating several caves. Here, in this tranquil setting of lush vegetation, fresh water springs and caves, Aristotle taught Alexander his companions.

I wander the pathways of the ancient site under tree branches where wild figs and grapes grow. On these shady walks and stone-tiered seats around the fountain dedicated to the Nymphs, Alexander was initiated into philosophy, poetry, mathematics and natural sciences. I enter the largest cave. Carved lintels lead to damp passageways. Stalactites drip from the ceilings. I imagine the voices of boys echoing from the past.

The original capital of Macedonia was at Aigai (near modern Vergina) a short distance from the town of Veria. It’s a pleasant half-hour walk from the village to the palace site. This big palace, built on a high promontory overlooking the plan with the sombre mountains close behind it, was a favourite hunting lodge for Philip. It was here that young Alexander often spent time with his father.Just below the lower terrace of the palace is the small theatre where Philip was assassinated as he attended a celebration for the wedding of Alexander’s sister Kleopatra.

As I stand looking out over the ruined tiers, I try to image the scene on that fateful day. The wedding was to be a big show with carts bearing statues of the twelve gods, including one with an effigy of Philip crowned as a god. As Philip entered the theatre and dismounted from his horse, he was stabbed to death by his bodyguard. The assassin dashed out of the theatre but was overtaken and killed. Family and political intrigues were behind the murder. At the time, Alexander was estranged from his father. His mother, Olympias, a ruthless, impassioned woman, was jealous of her rivals. Soon afterwards she had Phlip’s newest wife and infant daughter murdered.

As I stand looking out over the ruined tiers, I try to image the scene on that fateful day. The wedding was to be a big show with carts bearing statues of the twelve gods, including one with an effigy of Philip crowned as a god. As Philip entered the theatre and dismounted from his horse, he was stabbed to death by his bodyguard. The assassin dashed out of the theatre but was overtaken and killed. Family and political intrigues were behind the murder. At the time, Alexander was estranged from his father. His mother, Olympias, a ruthless, impassioned woman, was jealous of her rivals. Soon afterwards she had Phlip’s newest wife and infant daughter murdered.

Philip is interred in the royal tombs located a short walking distance below the palace on the plain. Found in a farmer’s field in 1976 and excavated, the tombs remain under the earth mound where they were discovered and entrance is through an underground passage.

Alexander would have been buried there in the tradition of the Macedonian kings, however his body was hijacked while it was being transported from Babylon and taken to Egypt where it was supposedly interred in a magnificent glass sarcophagus.

The new Tomb Museum incorporates several royal tombs and all the treasures found in them.As I climb down the stone steps to the tombs, tears fill my eyes. To me, this experience is as precious as the wealth of gold taken from the graves. All the years I have read and researched about Alexander, I have never imagined that one day I would stand before the graves of his legendary father and possibly that of his son, Alexander IV.

Philip’s tomb, a small marble temple, was hastily finished after the king’s sudden death. A young woman, identified s one of his barbarian wives, was buried with him. It is said that Alexander gave his father a Homeric funeral, fashioned after that of brave Hector in The Iliad. Items from the cremation pyre are displayed and they include pottery shards, pieces of weaponry, remnants of food offerings and harnesses from horses.

Next to Philip’s tomb is that of a Macedonian prince, believed to be Alexander IV, who was murdered at age 14. His remains are in the silver funeral urn that is displayed along with other grave offerings and a golden oak wreath.

Alexander became king at the age of 20. At the time of his assassination, Philip had been about to start a campaign against the Persians. Wishing to excel over his father and rival his glory, Alexander took up the challenge and marched eastward to conquer the world. Centuries later he is still revered as one of the greatest warriors the world has ever known.

Back in Thessalonki, as I ponder the two wreaths at the base of his monument, a group of Macedonian youths skateboard around it, dodging the rows of shields and sarissas that are the emblems of Alexander’s mighty army. I’m certain Alexander is smiling an approval.

Thessaloniki Private Historic Walking Tour

If You Go:

Getting Around: There is frequent daily bus and train service from Athens and from Thessaloniki to other parts of northern Greece.

Where to Stay: Reasonably priced hotels are available near the Thessaloniki train depot. Check with the local tourist-information office for pensions and hostels. There are good hotels in Veria but limited accommodations in Vergina. Samothraki has pensions and hotels at Kamariotissa near the ferry port.

Other Sites:

♦ Chaironeia, northeast of Athens, is the site of a decisive battle in 338 BC that established Philip II as ruler of the Greek city-states.

♦ Delphi, on the slopes of Mt. Parnassus, was a shrine of Apollo, God of the sun, music, reason and wisdom. Alexander came here to consult the priestess Pythia.

♦ Dion, one of the most important Macedonian shrines, is located on the north side of Mt. Olympus on a wide plain

♦ Dodoni, in the Pinos mountains of Epiros, was the home of Olympias, and Alexander spent much of his youth here.

♦ Mieza, near Naoussa, is where Aristotle taught the boys during Alexander’s early youth.

About the author:

Ruth spent a number of years researching and writing a novel dealing with the fall of Alexander’s dynasty. “Shadow of the Lion” is currently making the round of publishers. During the time she researched the novel, she lived in Greece and spends nearly every year visiting there. She also used her research trips to write travel articles about Greece and the country’s history. www.ruthkozak.com

Photo credits:

Alexander the Great statue by Classical Languages / CC BY

Alexander mosaic by Berthold Werner / Public domain

All other photos by Ruth Kozak

Green fields are patched with crops of yellow mustard, and splashes of brilliant red poppies carpet upland meadows where flocks of sheep graze idly in the sun. Across the Plain, sunlight glitters off the snow-covered peaks of Mounts Pelion and Parnassus. An eagle soars above a distant crag. Suddenly, out of the plain, gigantic spires of rock emerge, some higher than 400 meters, their strange shapes jutting up out of the fertile soil. Nothing I have seen in pictures has prepared me for this sight. Few places I have seen in Greece are so intensely dramatic.

Green fields are patched with crops of yellow mustard, and splashes of brilliant red poppies carpet upland meadows where flocks of sheep graze idly in the sun. Across the Plain, sunlight glitters off the snow-covered peaks of Mounts Pelion and Parnassus. An eagle soars above a distant crag. Suddenly, out of the plain, gigantic spires of rock emerge, some higher than 400 meters, their strange shapes jutting up out of the fertile soil. Nothing I have seen in pictures has prepared me for this sight. Few places I have seen in Greece are so intensely dramatic. Early next morning, I ride up to the Meteora in the small bus provided for tourists. The road passes the village of Kastraki and winds past the rock pinnacles where you can see the remains of ascetics’ caves, many walled off with rocks and rotting timbers.

Early next morning, I ride up to the Meteora in the small bus provided for tourists. The road passes the village of Kastraki and winds past the rock pinnacles where you can see the remains of ascetics’ caves, many walled off with rocks and rotting timbers. The first monastery you see as you approach is St Nicholas Anapafsas, built in 1527. It clings to the top ledge of an enormous rock. Uninhabited for years, its superb wall paintings by artist-monk Theophanes have now been restored.

The first monastery you see as you approach is St Nicholas Anapafsas, built in 1527. It clings to the top ledge of an enormous rock. Uninhabited for years, its superb wall paintings by artist-monk Theophanes have now been restored. Agia Tria, the Holy Trinity, built by the monk Dometius in the late 1400s, is on a pinnacle reached by a circular flight of 140 steps. The view is staggering. I feel suspended in a breathless void.

Agia Tria, the Holy Trinity, built by the monk Dometius in the late 1400s, is on a pinnacle reached by a circular flight of 140 steps. The view is staggering. I feel suspended in a breathless void.

As I watched the glorious sunset from the Venetian-style lighthouse, Fenari, I contemplated the many tragedies that have befallen this beautiful island.

As I watched the glorious sunset from the Venetian-style lighthouse, Fenari, I contemplated the many tragedies that have befallen this beautiful island. The harbor of Vathi is surrounded by houses with red-tiled roofs. Cafes animate the waterfront. The summer evening is scented with the smoke of grilling kebabs and fresh-caught fish grilling over charcoal coals. There is a curious atmosphere here. Ithaka’s hillsides are scented with wild sage and oregano, dotted with vibrant wild-flowers and silvery olive groves. Surrounding the tranquil orchards and vineyards are the high menacing mountains.

The harbor of Vathi is surrounded by houses with red-tiled roofs. Cafes animate the waterfront. The summer evening is scented with the smoke of grilling kebabs and fresh-caught fish grilling over charcoal coals. There is a curious atmosphere here. Ithaka’s hillsides are scented with wild sage and oregano, dotted with vibrant wild-flowers and silvery olive groves. Surrounding the tranquil orchards and vineyards are the high menacing mountains. It’s an Odyssey in itself just getting off Ithaka. The taxi picked me up as scheduled in order to make the sailing to Lefkada. I enjoyed the scenic drive and arrive in plenty of time, but fifteen minutes before the ferry was due to arrive, I discovered that the ferry that had broken down, and we must leave from a different port. After a hair-raising wild race by taxi on a twisting road with hairpin curves and precipices, I arrived at the port just minutes before the ferry sailed.

It’s an Odyssey in itself just getting off Ithaka. The taxi picked me up as scheduled in order to make the sailing to Lefkada. I enjoyed the scenic drive and arrive in plenty of time, but fifteen minutes before the ferry was due to arrive, I discovered that the ferry that had broken down, and we must leave from a different port. After a hair-raising wild race by taxi on a twisting road with hairpin curves and precipices, I arrived at the port just minutes before the ferry sailed. Sailing past Cape Doukas, the towering white cliffs rise from a sea that is as blue as a robin’s egg. The Cape looks like a gigantic wedge of cake with a lighthouse on top for a candle.

Sailing past Cape Doukas, the towering white cliffs rise from a sea that is as blue as a robin’s egg. The Cape looks like a gigantic wedge of cake with a lighthouse on top for a candle. The boat circled the island of Skorpios, a small island, densely wooded with cypress and pine trees. The red-tiled roofs of the Onassis’ villas are half-hidden behind the trees. In each little cover there are piers, each with a palm tree planted at the end. Around the dock areas, the grounds are landscaped and showers of magenta bougainvillea spill over the stone fences. One of these villas was a gift to opera singer Maria Callas in the days before Onassis abandoned her in favor of Jacqueline Kennedy.

The boat circled the island of Skorpios, a small island, densely wooded with cypress and pine trees. The red-tiled roofs of the Onassis’ villas are half-hidden behind the trees. In each little cover there are piers, each with a palm tree planted at the end. Around the dock areas, the grounds are landscaped and showers of magenta bougainvillea spill over the stone fences. One of these villas was a gift to opera singer Maria Callas in the days before Onassis abandoned her in favor of Jacqueline Kennedy.

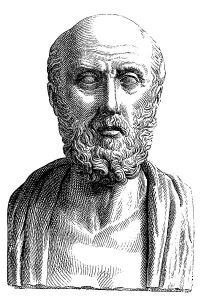

Hippocrates Tree is located in Kos Town. It is said Hippocrates stood under this plane-tree and lectured his medical students. Although it is unlikely that it is the actual tree under which Hippocrates stood, a far more plausible explanation is that the current tree is a descendant of the one under which Hippocrates lectured. Many health establishments around the world have taken cuttings from this tree and planted them in their own grounds. Hippocrates tree is easy to distinguish as it is supported by a large metal framework. I could not help but feel impressed that a man to whom medicine owes so much might have once stood in this same spot.

Hippocrates Tree is located in Kos Town. It is said Hippocrates stood under this plane-tree and lectured his medical students. Although it is unlikely that it is the actual tree under which Hippocrates stood, a far more plausible explanation is that the current tree is a descendant of the one under which Hippocrates lectured. Many health establishments around the world have taken cuttings from this tree and planted them in their own grounds. Hippocrates tree is easy to distinguish as it is supported by a large metal framework. I could not help but feel impressed that a man to whom medicine owes so much might have once stood in this same spot.

The sick would visit the Asklepion which was staffed by several therapists, priests and later doctors. The patient stayed for a few days and might take part in massage, gymnastics, bathing and follow a special diet.

The sick would visit the Asklepion which was staffed by several therapists, priests and later doctors. The patient stayed for a few days and might take part in massage, gymnastics, bathing and follow a special diet. As you approach the Asklepion it opens out in front of you and you can clearly see the three levels that make it up. Naturally, the main temple to Asklepios is at the top. I made my way slowly to the top, partly due to the heat but also so as not to miss anything on the way. My guidebook informed me that the lower levels were once accommodation and that the second terrace contained smaller temples, including one to Apollo. The authentic columns, arches and stone steps still look impressive and make you wonder about the people who used the Asklepios as a centre of healing all those years ago.

As you approach the Asklepion it opens out in front of you and you can clearly see the three levels that make it up. Naturally, the main temple to Asklepios is at the top. I made my way slowly to the top, partly due to the heat but also so as not to miss anything on the way. My guidebook informed me that the lower levels were once accommodation and that the second terrace contained smaller temples, including one to Apollo. The authentic columns, arches and stone steps still look impressive and make you wonder about the people who used the Asklepios as a centre of healing all those years ago.

Hidden on the slopes of a great rock known as the Gibraltar of Greece, Monemvasia is one of those rare treasures that tourists usually by-pass. It’s a magical experience visiting this little medieval site. The entire town is walled and invisible from the shore. The steep rock, crowned with its Venetian fortress, is connected to the mainland by a narrow causeway. Motor vehicles are prohibited, but a mini bus takes you free of charge to the old city gates.

Hidden on the slopes of a great rock known as the Gibraltar of Greece, Monemvasia is one of those rare treasures that tourists usually by-pass. It’s a magical experience visiting this little medieval site. The entire town is walled and invisible from the shore. The steep rock, crowned with its Venetian fortress, is connected to the mainland by a narrow causeway. Motor vehicles are prohibited, but a mini bus takes you free of charge to the old city gates.

From Monemvasia I took the early morning bus heading for Koroni, another Venetian town. After a circuitous route through Sparta, I arrived at Koroni that evening. The castle of Koroni was lit by a mystic green light. Above its turrets, Mars blinked its red beacon; a crescent moon illuminated the sky over the twinkling lights of the village; little kaikis bobbed on the moonlit sea.

From Monemvasia I took the early morning bus heading for Koroni, another Venetian town. After a circuitous route through Sparta, I arrived at Koroni that evening. The castle of Koroni was lit by a mystic green light. Above its turrets, Mars blinked its red beacon; a crescent moon illuminated the sky over the twinkling lights of the village; little kaikis bobbed on the moonlit sea. The old town of Koroni has long since fallen into ruin, but the Venetian architecture has been preserved, with wrought iron balcony railings, arched windows and doors. The largest, two-storied mansions and public buildings are on the waterfront, while higher up are the smaller Laika (folk) houses with small inner courtyards. One distinctive feature of the Koroni houses are the curved tile roofs and unusual terracotta eave decorations: instead of the usual palmettes, these are like small winged angels.

The old town of Koroni has long since fallen into ruin, but the Venetian architecture has been preserved, with wrought iron balcony railings, arched windows and doors. The largest, two-storied mansions and public buildings are on the waterfront, while higher up are the smaller Laika (folk) houses with small inner courtyards. One distinctive feature of the Koroni houses are the curved tile roofs and unusual terracotta eave decorations: instead of the usual palmettes, these are like small winged angels. Which set of the many instructions, bus schedules, and info that I was given by Greek locals would prove to be the right one? After various suggestions I decided to go with the English speaking baker who even drew me a map to explain which village to get off to catch the bus to Pylos/Methoni which, he said, went past every hour. According to his directions, I disembarked at the cross-roads at a village called Rozymalos and waited at a kafeneion for just over an hour until the bus finally arrived.

Which set of the many instructions, bus schedules, and info that I was given by Greek locals would prove to be the right one? After various suggestions I decided to go with the English speaking baker who even drew me a map to explain which village to get off to catch the bus to Pylos/Methoni which, he said, went past every hour. According to his directions, I disembarked at the cross-roads at a village called Rozymalos and waited at a kafeneion for just over an hour until the bus finally arrived. Methoni’s 15th century Venetian fortress expands over the whole area of the south west cape. Built over ancient walls, it was the prize of many invaders over the ages. The walls loom imposingly over a setting filled with memories of the past. The castle has a protective moat on the land side and is surrounded on three sides by the sea making it impenetrable.

Methoni’s 15th century Venetian fortress expands over the whole area of the south west cape. Built over ancient walls, it was the prize of many invaders over the ages. The walls loom imposingly over a setting filled with memories of the past. The castle has a protective moat on the land side and is surrounded on three sides by the sea making it impenetrable.