Southern Italy and Sicily

by Troy Herrick

Centuries before the Romans conquered southern Italy and Sicily, the Greeks had already colonized the hospitable coastlines here. The Greek population was so large that the Romans referred to these two regions as Magna Grecia (Greater Greece). The process of settling Greater Greece was the original “How the West was Won”.

Paestum on the Italian mainland plus Agrigento and Syracuse on Sicily are the three best Greek settlements for touring. Paestum has three of the most complete Greek temples in Italy. Agrigento boasts the Valley of the Temples; Syracuse showcases an ancient Greek theatre and several temple sites. Each of these UNESCO World Heritage Sites also has a museum displaying a wealth of Greek items. All three sites are easily accessible and make for great day trips into the past.

Paestum

Greeks established Paestum in 600 BCE as “Poseidonia” in honor of their sea god Poseidon. The Lucanians would conquer this city two centuries later but not before its Hellenic residents built three temples, now some of the best preserved in Italy.

All three temples face eastward, presumably to allow the rising sun to shine on any deity statues inside. Furthermore, they are close together on flat terrain which allows for easy comparison. Having these three large structures so close to the road as you arrive is intimidating. You almost feel like their respective deities are still inside demanding your worship and sacrifices.

All three temples face eastward, presumably to allow the rising sun to shine on any deity statues inside. Furthermore, they are close together on flat terrain which allows for easy comparison. Having these three large structures so close to the road as you arrive is intimidating. You almost feel like their respective deities are still inside demanding your worship and sacrifices.

The Temple of Hera at the southern end of the archeological site was built around 550 BCE. All of the fifty greyish sandstone columns forming the peristyle remain upright. Unusual for temples at other Greek cities, remnants of a small sacrificial altar grace the front of the structure rather than the interior.

The neighboring Temple of Poseidon, dating to 450 BCE, is the largest and best preserved structure on site. Thirty-six honey brown travertine columns form the peristyle. This temple reflects the transition between the Archaic and later Doric styles. Again the remains of two altars are located in front of the structure. Only the larger altar is of Greek origin; the smaller is Roman.

The neighboring Temple of Poseidon, dating to 450 BCE, is the largest and best preserved structure on site. Thirty-six honey brown travertine columns form the peristyle. This temple reflects the transition between the Archaic and later Doric styles. Again the remains of two altars are located in front of the structure. Only the larger altar is of Greek origin; the smaller is Roman.

The grey limestone Temple of Ceres, built about 500 BCE, is a short walk to the north. This temple with 34 columns is the first anywhere in the Greek world to display a transition between the Doric and later Ionic styles. Remnants of an altar are found in front of this temple as well. Three medieval Christian tombs were installed under the floor indicating that this temple was once a Christian church.

The Ekklesiasterion is located just inside the park fence, opposite the museum. The circular, limestone oratory was the site of democratic assembly for this city-state. This low-lying structure has 10 levels of seats.

The Ekklesiasterion is located just inside the park fence, opposite the museum. The circular, limestone oratory was the site of democratic assembly for this city-state. This low-lying structure has 10 levels of seats.

Cross the road to the Archeology Museum of Paestum. This museum features local objects collected from the Greek, Lucanian and finally the Roman periods. Prized Greek items include metopes taken from another Temple of Hera several kilometres north of Paestum, 6th century BCE bronze vases decorated with rams and sphinxes, black and brown pottery, bronze helmets and breast plates.

Agrigento

The Valley of the Temples at Agrigento is all that remains of the ancient Greek city of “Akragas”. Founded in 582 BCE, residents would construct eight temples over the next century. Of these, only five are accessible on site.

The Valley of the Temples at Agrigento is all that remains of the ancient Greek city of “Akragas”. Founded in 582 BCE, residents would construct eight temples over the next century. Of these, only five are accessible on site.

Your step back in time begins with a panoramic view of ancient structures peeking out from behind groves of trees to pique your curiosity. The five Doric temples, in various states of disrepair, are set on a ridge and not in a valley. Arriving on site, you find that the park is divided into two separate sections, each with its own entrance.

The Temple of Concordia, constructed around 430 BCE is the best preserved. All 34 honey brown calcarenite columns remain standing. This structure was saved from destruction because it was transformed into a Christian basilica in 597 CE. A Christian necropolis used between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE is located nearby.

The Temple of Hera stands at the highest point of the ridge. Twenty five of its 34 honey brown calcarenite columns remain standing, making it the second best preserved temple in the park. This temple was constructed between 450 and 440 BCE.

The Temple of Hera stands at the highest point of the ridge. Twenty five of its 34 honey brown calcarenite columns remain standing, making it the second best preserved temple in the park. This temple was constructed between 450 and 440 BCE.

Long ago earthquakes toppled the remaining three temples. Much of their debris was recycled for other structures in the area. The temple of Heracles is the oldest of these three temples, having been constructed about 500 BCE. Eight of its original 38 honey brown columns were partially restored in 1923 by the Englishman Alexander Herdenstel.

Exit this side of the park to visit the last two temples. The first is the Temple of Castor and Pollux (Dioscuri). Four of the 34 honey brown columns remain standing amidst fruit-laden olive trees. Here visitors find that Greek-style columns were not one solid cylinder. Rather they were assembled from several cylindrical drums. The end of one of these drums features a square indentation. A wooden peg may have been set in this indentation as a means of aligning and stabilizing the drums as they were stacked one upon the other. Visitors should note that some of the drums on site may have belonged to other structures at one time.

Exit this side of the park to visit the last two temples. The first is the Temple of Castor and Pollux (Dioscuri). Four of the 34 honey brown columns remain standing amidst fruit-laden olive trees. Here visitors find that Greek-style columns were not one solid cylinder. Rather they were assembled from several cylindrical drums. The end of one of these drums features a square indentation. A wooden peg may have been set in this indentation as a means of aligning and stabilizing the drums as they were stacked one upon the other. Visitors should note that some of the drums on site may have belonged to other structures at one time.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus is now in total ruins but in its time it was the largest Doric temple ever constructed. History records that construction was never fully completed. Unlike many other Greek temples of the period, the spaces between its columns were walled in. This was in part facilitated by incorporating 25-foot high human figures known as telamons to support the building. The telamon on site is only a copy; one of the originals is exhibited in the Archaeology Museum.

You can put the Valley of the Temples into perspective with a tour of the Archeology Museum.

You can put the Valley of the Temples into perspective with a tour of the Archeology Museum.

This museum displays Agrigento-area objects from the pre-historic to Roman periods. Greek items include black and orange figured pottery, sarcophagi, coins, a bronze warrior helmet, wall paintings and 5th century BCE statues of various deities. You can also study a scale model of the Temple of Olympian Zeus. Note that each telamon only fills the upper half of each space between the columns. When you finish with the museum, tour the ruins on the grounds.

Syracuse

Syracuse was founded by the Greeks in 734 BCE. By 413 BCE, it had become the most powerful Greek city in the ancient world after defeating Athens in a great sea battle. Reminders of its Hellenic heritage are found throughout the city.

Arriving at the Neapolis Archeological Park you find little evidence of any ancient structures within. Your first impression is that of a quarry. Appearances are deceiving as the park actually includes the largest Greek theatre in Sicily. This theatre is hidden from view by trees. You only discover the structure when you arrive on site. Carved out of a limestone hill in the 6th century BCE, this theatre held 15,000 spectators in 67 rows of seats. A tunnel around the periphery may have allowed people to enter and exit the theatre quickly. The upper level of the structure features a number of arches carved out of the solid rock as small “grottos”. One of these holds a small waterfall inside. Compare this Greek theatre to the nearby 3rd century CE Roman amphitheatre. The Greek theatre is semicircular and open while the Roman structure is oval and enclosed.

Arriving at the Neapolis Archeological Park you find little evidence of any ancient structures within. Your first impression is that of a quarry. Appearances are deceiving as the park actually includes the largest Greek theatre in Sicily. This theatre is hidden from view by trees. You only discover the structure when you arrive on site. Carved out of a limestone hill in the 6th century BCE, this theatre held 15,000 spectators in 67 rows of seats. A tunnel around the periphery may have allowed people to enter and exit the theatre quickly. The upper level of the structure features a number of arches carved out of the solid rock as small “grottos”. One of these holds a small waterfall inside. Compare this Greek theatre to the nearby 3rd century CE Roman amphitheatre. The Greek theatre is semicircular and open while the Roman structure is oval and enclosed.

A short walk outside the park brings you to the Paolo Orsi Regional Archeology Museum. Recovered items date from the mid Bronze Age to the 5th century BCE and include Greek statuettes, orange and black glazed pottery, spear points, ax heads and a sickle. Scale models of the Temples of Athena and Apollo put the remnants of these local structures into perspective.

Leave the Museum and walk to Ortygia Island, the historic center of Syracuse, for more Greek history. Your first destination is the remains of the 6th century BCE Doric Temple of Apollo. Only two of its 42 grey limestone columns and a section of wall remain standing. This temple is in a serious state of disrepair after last having been used as a church during the Norman period almost one thousand years ago. The temple grounds are fenced off from the public.

Leave the Museum and walk to Ortygia Island, the historic center of Syracuse, for more Greek history. Your first destination is the remains of the 6th century BCE Doric Temple of Apollo. Only two of its 42 grey limestone columns and a section of wall remain standing. This temple is in a serious state of disrepair after last having been used as a church during the Norman period almost one thousand years ago. The temple grounds are fenced off from the public.

A short walk away, you find a 7th century CE Duomo decorated with a Baroque façade. Inside, ten greyish brown columns have been incorporated into the side walls of the nave. These columns are all that remains of the 5th century BCE Doric Temple of Athena.

In Summary

Paestum, Agrigento and Syracuse are three different perspectives of ancient Greek society. Their respective colonists were intent on permanent settlement and except for Paestum they were largely successful. None of these sites were cultural backwaters. Residents built all the amenities for self-sufficiency and eventually achieved a level of sophistication that was comparable to the cities that they left behind in their homeland.

Paestum Greek Ruins Private Tour

If You Go:

Paestum

♦ Paestum is 85 kilometers south east of Naples (39 kilometers south of Salerno) and is accessible by train. The train station is a 15-minute walk from the archeological site. Purchase the combination pass to the archeological site and the Archeology Museum of Paestum. The cost was 6.50 Euros at the time of my visit.

♦ Visitors cannot enter any of the temples at Paestum.

Agrigento

♦ Agrigento is 2 hours from Palermo by train.

♦ Take buses 1, 2 or 3 from the Agrigento train station to the Valley of the Temples. The bus fare was 1 Euro at the time of my visit.

♦ Purchase the combination pass for the Valley of the Temples and the museum. The cost was 10 Euros at the time of my visit.

♦ Visitors cannot enter any of the temples at Agrigento.

♦ The Archeology Museum is approximately 500 meters from the Valley of the Temples on Via dei Templi as you walk back toward Agrigento.

2-hour Private Valley of the Temples Tour in Agrigento

Syracuse

♦ Syracuse in at the end of the train line that also includes Messina, Taormina and Catania. Purchase the combination pass for the Neapolis Archeological Park (Parco Archeologico della Neapolis) and the Paolo Orsi Regional Archeology Museum (Museo Archeologico Regionale “Paolo Orsi”). The cost was 9 Euros at the time of my visit.

♦ The Neapolis Archeological Park is located at Via Del Teatro (off the intersection of Corso Gelone and Viale Teocrito).

♦ The Paolo Orsi Regional Archeology Museum is located at Viale Teocrito 66 approximately, 500 meters from the Parco Archeologico della Neapolis.

♦ The Temple of Apollo is located in the Piazza Pancali at Largo XXV Luglio and Corso Umberto in Ortygia.

♦ The Duomo is located in the Piazza Duomo.

Private tour to Syracuse – Archaeological Park and Ortigia with option of Food and Wine tasting

About the author:

Troy Herrick, a freelance travel writer, has traveled extensively in North America, the Caribbean, Europe and parts of South America. His articles have appeared in Live Life Travel, International Living, Offbeat Travel and Travel Thru History Magazines. He also penned the travel planning e-book entitled ”Turn Your Dream Vacation into Reality: A Game Plan for Seeing the World the Way You Want to See It” – www.thebudgettravelstore.com/page/76972202 based on his own travel experiences over the years. Plan your vacation at his www.thebudgettravelstore.com and www.plan-a-dream-trip.com

Photo credits:

All photos are by Diane Gagnon. She is a freelance photographer who has traveled extensively in North America, the Caribbean, Europe and parts of South America. Her photographs have accompanied Troy Herrick’s articles in Live Life Travel, Offbeat Travel and Travels Thru History Magazines.

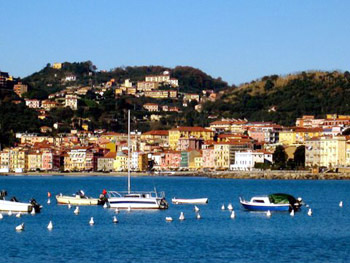

Percy and Mary Shelley arrived in the tiny seaside village of San Terenzo in 1819 and rented a villa known as “Casa Magni”, whose whitewashed walls and arched colonnade can be found on the promenade. “A lonely house close by the soft and sublime scenes of the Bay of Lerici”, is how Shelley described the villa in his letters. These lines are inscribed on the walls of the now uninhabited villa, along with “I still inhabit this Divine Bay, reading dramas and sailing and listening to the most enchanting music.”

Percy and Mary Shelley arrived in the tiny seaside village of San Terenzo in 1819 and rented a villa known as “Casa Magni”, whose whitewashed walls and arched colonnade can be found on the promenade. “A lonely house close by the soft and sublime scenes of the Bay of Lerici”, is how Shelley described the villa in his letters. These lines are inscribed on the walls of the now uninhabited villa, along with “I still inhabit this Divine Bay, reading dramas and sailing and listening to the most enchanting music.” A sprinkling of brightly coloured houses line medieval streets that wind up to Lerici’s castle, which overlooks the entrance to the Gulf of Poets. The castle is thought to be the inspiration for Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” Nowadays the castle contains a museum of palaeontology.

A sprinkling of brightly coloured houses line medieval streets that wind up to Lerici’s castle, which overlooks the entrance to the Gulf of Poets. The castle is thought to be the inspiration for Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” Nowadays the castle contains a museum of palaeontology. Shelley’s’ ashes were stored in the wine cellar of The British Consul in Rome before being buried in The Protestant Cemetery in Rome, where John Keats was laid to rest just a year before. After Mary Shelley’s death, her husband’s heart was found wrapped in a page of “Adonais”, Shelley’s famous elegy to Keats. Shelley’s heart was eventually buried in St Peter’s Churchyard in Bournemouth, Dorset.

Shelley’s’ ashes were stored in the wine cellar of The British Consul in Rome before being buried in The Protestant Cemetery in Rome, where John Keats was laid to rest just a year before. After Mary Shelley’s death, her husband’s heart was found wrapped in a page of “Adonais”, Shelley’s famous elegy to Keats. Shelley’s heart was eventually buried in St Peter’s Churchyard in Bournemouth, Dorset.

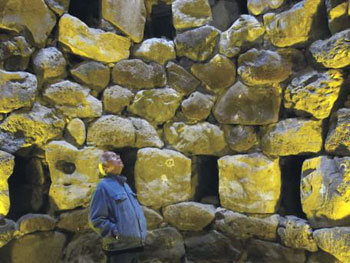

Today, there are more than 8,000 nuraghes still standing from what is estimated to have numbered more than 30,000. They were most prevalent in the northwest and south-central areas of the island and are usually located in a panoramic spot – strategically located on hilltops to control important passages.

Today, there are more than 8,000 nuraghes still standing from what is estimated to have numbered more than 30,000. They were most prevalent in the northwest and south-central areas of the island and are usually located in a panoramic spot – strategically located on hilltops to control important passages.

They all are incredibly accessible and available to explore. When you enter a nuraghe, stand in the middle of the cone and stare up at the opening above you, the presence of it’s former inhabitants is almost palpable. The stone stairs to the various interior levels wind-up the sides of the structure leading to antechambers and strange rooms. There is a strong sense of design and intention.

They all are incredibly accessible and available to explore. When you enter a nuraghe, stand in the middle of the cone and stare up at the opening above you, the presence of it’s former inhabitants is almost palpable. The stone stairs to the various interior levels wind-up the sides of the structure leading to antechambers and strange rooms. There is a strong sense of design and intention. Having stated that, it remains a complete mystery as to who were the Nuragic people. Some clues can be found at The National Archeological Museum in Cagliari. It holds most of the materials discovered in the Nuraghes. They did produce art in the form of beautiful small bronze statues; typically representing Gods, the chief of the village, soldiers, animals and women. There are also stone carvings or statues representing female divinities.

Having stated that, it remains a complete mystery as to who were the Nuragic people. Some clues can be found at The National Archeological Museum in Cagliari. It holds most of the materials discovered in the Nuraghes. They did produce art in the form of beautiful small bronze statues; typically representing Gods, the chief of the village, soldiers, animals and women. There are also stone carvings or statues representing female divinities. The sacred well of Santa Cristina has a hole in the vault. Every 18 and a half years, when the moon reaches is lowest point in orbit, the moonlight strikes the hole and is reflected on the surface of the water. Sunlight is also reflected during the autumn and spring equinoxes. Through these processes we know they possessed a great knowledge of celestial cycles.

The sacred well of Santa Cristina has a hole in the vault. Every 18 and a half years, when the moon reaches is lowest point in orbit, the moonlight strikes the hole and is reflected on the surface of the water. Sunlight is also reflected during the autumn and spring equinoxes. Through these processes we know they possessed a great knowledge of celestial cycles. But that is where the certainties end. Scholars are not even sure of the correct name for the civilization, or even the real meaning of nuraghe. The name itself derives from the meaning of mound and cavity, and the nuraghes are built by laying big stones of similar size on top of each other, leaving a cavity in the middle which is then covered by a stone domed roof. For lack of a more informed identification, scientists accordingly have called them the Nuragic peoples.

But that is where the certainties end. Scholars are not even sure of the correct name for the civilization, or even the real meaning of nuraghe. The name itself derives from the meaning of mound and cavity, and the nuraghes are built by laying big stones of similar size on top of each other, leaving a cavity in the middle which is then covered by a stone domed roof. For lack of a more informed identification, scientists accordingly have called them the Nuragic peoples.

I wonder what it would be like to live here in Abruzzo all the time, far from the pressures of city life, far from tourist traps, close to nature, and to inner peace. Like Celestine. Back in the thirteenth century, he lived higher up these rugged slopes, in a cave, until he was called to the Papacy. But he hated all the glitz and glamour, and missed his life as a hermit, so he swiftly issued a decree allowing popes to abdicate, and returned to his cave.

I wonder what it would be like to live here in Abruzzo all the time, far from the pressures of city life, far from tourist traps, close to nature, and to inner peace. Like Celestine. Back in the thirteenth century, he lived higher up these rugged slopes, in a cave, until he was called to the Papacy. But he hated all the glitz and glamour, and missed his life as a hermit, so he swiftly issued a decree allowing popes to abdicate, and returned to his cave. Yes, I think, turning back down the mountain, there’s a spiritual energy here. But I would want a little more material comfort than Celestine had: perhaps I could buy that stone ruin over there on the slope, and convert it. Like Ezio and Mariangela did. A few years ago, they decided to flee the pressures of city life, and bought an eighteenth century property here. They restored it using original materials, and made it into a four-bedroom B&B. They named it Casa Giumentina, after this valley. That’s where I’m staying…and I’m getting hungry. The sun is now warm on the back of my legs. As I approach the house, I see that breakfast has been laid out on the table under the oak tree. I can already smell the cappuccino…and Mariangela’s freshly baked apple cake.

Yes, I think, turning back down the mountain, there’s a spiritual energy here. But I would want a little more material comfort than Celestine had: perhaps I could buy that stone ruin over there on the slope, and convert it. Like Ezio and Mariangela did. A few years ago, they decided to flee the pressures of city life, and bought an eighteenth century property here. They restored it using original materials, and made it into a four-bedroom B&B. They named it Casa Giumentina, after this valley. That’s where I’m staying…and I’m getting hungry. The sun is now warm on the back of my legs. As I approach the house, I see that breakfast has been laid out on the table under the oak tree. I can already smell the cappuccino…and Mariangela’s freshly baked apple cake. As I enter the village, I notice that the roads have been recently paved. There’s a feeling of progress, of development. After the war, this was one of the most depressed areas in Italy. People left in their hundreds, looking for work, often in mines in northern Europe. The population dropped from 2000 to 450. But things are changing: people are trickling back.

As I enter the village, I notice that the roads have been recently paved. There’s a feeling of progress, of development. After the war, this was one of the most depressed areas in Italy. People left in their hundreds, looking for work, often in mines in northern Europe. The population dropped from 2000 to 450. But things are changing: people are trickling back.

‘My husband died in the war,’ she says. ‘I never married again. I couldn’t have my sons calling another man “papà”.’

‘My husband died in the war,’ she says. ‘I never married again. I couldn’t have my sons calling another man “papà”.’ I stroll down to Il Carro, a restaurant which serves local delicacies. I start with an antipasto of salame and pecorino cheese, then have wild boar, with spelt, which is the staple cereal in this area. I accompany it with a glass of Montepulciano wine, and finish up with a fresh strawberry sorbet and an espresso.

I stroll down to Il Carro, a restaurant which serves local delicacies. I start with an antipasto of salame and pecorino cheese, then have wild boar, with spelt, which is the staple cereal in this area. I accompany it with a glass of Montepulciano wine, and finish up with a fresh strawberry sorbet and an espresso. But no, here is where I want to be. The view is too beautiful. I feel warm and relaxed. I’ll sit in a deckchair and read, or write, or perhaps just gaze into space until sunset.

But no, here is where I want to be. The view is too beautiful. I feel warm and relaxed. I’ll sit in a deckchair and read, or write, or perhaps just gaze into space until sunset. We chop and stir together in the large kitchen. Before settling down to dinner on the terrace I slip on a cardigan. Up here, fifteen hundred feet above the sultry plains below, the evening air is cool.

We chop and stir together in the large kitchen. Before settling down to dinner on the terrace I slip on a cardigan. Up here, fifteen hundred feet above the sultry plains below, the evening air is cool.

Entering ancient Porta Marina’s pedestrians-only passage, our guide introduces Pompeii. “Just like now, thousands of visitors traveled here,” Massimillio informs us. “And many different languages were spoken.”

Entering ancient Porta Marina’s pedestrians-only passage, our guide introduces Pompeii. “Just like now, thousands of visitors traveled here,” Massimillio informs us. “And many different languages were spoken.”

Wealthy nobles lived along via de la Fortuna where elegant homes covered with bright-white ground-marble stucco stood next door to smaller houses. At House of the Faun, an undamaged mosaic displaying the original sign HAVE meaning ‘hail-to-you,’ welcomes us into the entrance hall and open courtyards. Then covering an entire block, its forty stylish rooms included magnificent dining rooms, one for each season. Carved columns had lined two immense gardens filled with marble and bronze statuary and beautiful fountains.

Wealthy nobles lived along via de la Fortuna where elegant homes covered with bright-white ground-marble stucco stood next door to smaller houses. At House of the Faun, an undamaged mosaic displaying the original sign HAVE meaning ‘hail-to-you,’ welcomes us into the entrance hall and open courtyards. Then covering an entire block, its forty stylish rooms included magnificent dining rooms, one for each season. Carved columns had lined two immense gardens filled with marble and bronze statuary and beautiful fountains. Nearby, the House of the Vetti belonged to bachelor brothers, prosperous wine-merchants. This patrician villa retains original mosaics in green jade, white Carrera marble and indigo-blue onyx; vibrantly colored frescoes decorate well-preserved entertainment rooms. At a smaller house next door, we linger over frescoes in rich earthen tones depicting delicate flowers and winged cherubs, among my favorites for their simple whimsy.

Nearby, the House of the Vetti belonged to bachelor brothers, prosperous wine-merchants. This patrician villa retains original mosaics in green jade, white Carrera marble and indigo-blue onyx; vibrantly colored frescoes decorate well-preserved entertainment rooms. At a smaller house next door, we linger over frescoes in rich earthen tones depicting delicate flowers and winged cherubs, among my favorites for their simple whimsy. Raised sidewalks wind along the street to one of the 34 bakeries needed to feed Pompeii’s population of over 20,000. “Those squat towers made of volcanic stones milled flour on-site,” reports our guide. Amazed that the well-built ovens so closely resemble today’s brick pizza ovens, we imagine tantalizing aromas floating on the air. During excavations, centuries-old loaves of blackened breads were found inside many ovens.

Raised sidewalks wind along the street to one of the 34 bakeries needed to feed Pompeii’s population of over 20,000. “Those squat towers made of volcanic stones milled flour on-site,” reports our guide. Amazed that the well-built ovens so closely resemble today’s brick pizza ovens, we imagine tantalizing aromas floating on the air. During excavations, centuries-old loaves of blackened breads were found inside many ovens. Inside, surprisingly small cells held stone beds once covered by mattresses. Using a separate entrance, wealthier clients had used the more private second-story rooms bedecked with rich frescoes leaving little to the imagination.

Inside, surprisingly small cells held stone beds once covered by mattresses. Using a separate entrance, wealthier clients had used the more private second-story rooms bedecked with rich frescoes leaving little to the imagination. Onward past a former Temple of popular Egyptian goddess Isis, we pause among columns remaining in a second public Forum. This is where theatergoers had mingled in bars and cafes before open-air performances at their Grande Theater. First built in the 2nd-century BC, this theater seated over 5000 citizens in three price ranges. Its smaller semi-circular neighbor, the Odeon staged more intimate mime, plays and musical events.

Onward past a former Temple of popular Egyptian goddess Isis, we pause among columns remaining in a second public Forum. This is where theatergoers had mingled in bars and cafes before open-air performances at their Grande Theater. First built in the 2nd-century BC, this theater seated over 5000 citizens in three price ranges. Its smaller semi-circular neighbor, the Odeon staged more intimate mime, plays and musical events.