by Ana Ruiz

The rich history of Málaga goes as far back as the 8th century BCE when the Phoenicians founded the trade settlement here they named Malacca. The name is derived from the Punic, malac meaning ‘salt’, as Málaga was founded as a fish-salting settlement. The Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Visigoths, and Moors all left their mark here and throughout the centuries, Málaga continued to thrive as a chief settlement and established harbor. Today, the port of Málaga stands as the second largest in Spain after Barcelona.

The rich history of Málaga goes as far back as the 8th century BCE when the Phoenicians founded the trade settlement here they named Malacca. The name is derived from the Punic, malac meaning ‘salt’, as Málaga was founded as a fish-salting settlement. The Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Visigoths, and Moors all left their mark here and throughout the centuries, Málaga continued to thrive as a chief settlement and established harbor. Today, the port of Málaga stands as the second largest in Spain after Barcelona.

Of the eight provinces of Andalusia (Spain’s southern region), Málaga is actually the smallest in size, however, it stands proudly as capital of and gateway to the Costa del Sol (Coast of the Sun.) However, Málaga City is often overlooked by tourists who travel directly from the airport to such popular resort towns as Marbella and Torremolinos while missing out on the great historical and cultural wealth this cosmopolitan capital city has to offer. Málaga City is best explored on foot as the major attractions, such as sunny beaches, galleries, museums, parks, boutiques, restaurants, bars, cafes, and historic sites, are all within walking distance.

The first time I landed at the Pablo Picasso International Airport, I was pleasantly surprised by the display of reproductions of the Málaga-born artist that adorned the walls of the corridor of Terminal T2 known as Pablo Ruiz Picasso. Art-lovers can visit the Museo Picasso Málaga located in the city center dedicated to exhibiting over 200 of his works. At the nearby Plaza de la Merced, stands the birthplace or Casa Natal where the famous artist was born in 1881. Just over a century later, it was declared an official heritage site and today, it stands as a foundation promoting his works.

The first time I landed at the Pablo Picasso International Airport, I was pleasantly surprised by the display of reproductions of the Málaga-born artist that adorned the walls of the corridor of Terminal T2 known as Pablo Ruiz Picasso. Art-lovers can visit the Museo Picasso Málaga located in the city center dedicated to exhibiting over 200 of his works. At the nearby Plaza de la Merced, stands the birthplace or Casa Natal where the famous artist was born in 1881. Just over a century later, it was declared an official heritage site and today, it stands as a foundation promoting his works.

Not far from the Pablo Picasso Museum stands the bullring, Plaza de Toros de La Malagueta, and bullfighting museum, Museo Taurino Antonio Ordóńez. The arena accommodates up to 14,000 spectators during bullfights that are held here between April and September each year.

Although, I am not a fan of the sport, I decided to visit at a time when no bullfights were scheduled. I ventured out into the vast bullring and I have to admit that it was quite impressive and strangely peaceful. After a few minutes, I noticed two young boys in the middle of the ring who were practicing or training to become bullfighters or matadors. The boys had cleverly attached what looked like set of horns to a type of cart that was wheeled by one boy as he constantly rammed his way towards the other who was gracefully dodging and darting his way, almost as if dancing, while maneuvering his cape. I smiled and thought to myself that I much rather preferred to have seen this than an actual bullfight!

Although, I am not a fan of the sport, I decided to visit at a time when no bullfights were scheduled. I ventured out into the vast bullring and I have to admit that it was quite impressive and strangely peaceful. After a few minutes, I noticed two young boys in the middle of the ring who were practicing or training to become bullfighters or matadors. The boys had cleverly attached what looked like set of horns to a type of cart that was wheeled by one boy as he constantly rammed his way towards the other who was gracefully dodging and darting his way, almost as if dancing, while maneuvering his cape. I smiled and thought to myself that I much rather preferred to have seen this than an actual bullfight!

Barely a 15 minute walk from the bullring brings you to the Museo de Arte Flamenco de Málaga. Filled with fascinating memorabilia, the museum exhibits flamenco guitars, traditional colorful costumes, vintage recordings dating back to the 19th century, as well as numerous photographs and lithographs of famous local Flamenco performers of the past. Flamenco shows are held here on Friday nights at the Peńa Juan Breva located in lower level of the building.

However, when it comes to Flamenco performances for visitors, the most highly recommended venue is the restaurant Vino Mio located in the city center. Every night, shows are held here between 8 to 9:30 PM in order to accommodate tourists as most Flamenco shows begin much later in the evening. A 4€ supplement is added to the meal if you wish to enjoy the performance.

A 5-minute walk from the restaurant will bring you to a bright orange building where Málaga’s wine museum or Museo del Vino is located. Málaga has been celebrated for its sweet wines since the Phoenicians arrived, and throughout the centuries, the Greeks, Romans, and Moors continued to develop their own particular varieties. Today, over 2 million liters of wine is produced in the province of Málaga each year.

The wine museum is housed in an 18th century building where guided tours teach you about the history and culture of the wines made in the province. The 5€ entrance fee covers the cost of two wine samples of the more than 100 different varieties available. Wine-tasting tours to the wineries on the outskirts of town can also be arranged. Amusingly, a particular chain of bodegas situated in the province of Málaga are named Quitapenas, or “sorrow-removers”.

A 10-minute walk from the wine museum will take you to the magnificent Roman and Moorish vestiges located in the eastern part of the city. The Moorish structures include the 11th century fortress or Alcazába and the 14th century Gibralfaro Castle; both built by the Moors over Roman ruins upon a hill overlooking the city and harbor. The Alcazába is considered as one of the best preserved Moorish fortresses in the country. The fortress once stood as the royal residence of Sultans and today stands as a true landmark of the city adorned with Caliphal arches, majestic courtyards, tiled patios, look-out towers, and jasmine-scented gardens. Ornamental fountains and pools decorate the tranquil grounds leaving one with a sense of peace from the soothing sounds of trickling water that can be heard throughout the grounds as is customary to Muslim tradition.

A 10-minute walk from the wine museum will take you to the magnificent Roman and Moorish vestiges located in the eastern part of the city. The Moorish structures include the 11th century fortress or Alcazába and the 14th century Gibralfaro Castle; both built by the Moors over Roman ruins upon a hill overlooking the city and harbor. The Alcazába is considered as one of the best preserved Moorish fortresses in the country. The fortress once stood as the royal residence of Sultans and today stands as a true landmark of the city adorned with Caliphal arches, majestic courtyards, tiled patios, look-out towers, and jasmine-scented gardens. Ornamental fountains and pools decorate the tranquil grounds leaving one with a sense of peace from the soothing sounds of trickling water that can be heard throughout the grounds as is customary to Muslim tradition.

The Gibralfaro Castle is actually older than the Alcazába as it dates to the 10th century, however, it was during the 14th century when it was rebuilt and enlarged in order to protect the Alcazába that was otherwise vulnerable to attacks approaching from the hills. During the days of Muslim rule, the sea reached all the way to what once were the lower ramparts. Today, spectacular views of the city, bullring, and port can be appreciated from the Gibralfaro Castle.

The Gibralfaro Castle is actually older than the Alcazába as it dates to the 10th century, however, it was during the 14th century when it was rebuilt and enlarged in order to protect the Alcazába that was otherwise vulnerable to attacks approaching from the hills. During the days of Muslim rule, the sea reached all the way to what once were the lower ramparts. Today, spectacular views of the city, bullring, and port can be appreciated from the Gibralfaro Castle.

As if these Moorish vestiges were not enough, ruins of a vast 1st century BCE Roman stadium or amphitheater lie at the foot of the entrance to the Alcazába. To build their fortress, the Moors actually recycled blocks of the Roman arena that once accommodated as many as 20,000 spectators. The grandness of the stadium reflects the significance of Roman Málaga during its day. Yet, throughout the centuries to the present, Málaga continues to thrive as a vibrant city offering a multitude of cultural attractions and charming historical sites.

Walking Tour of Malaga with entrance to Picasso and or Thyssen Museums

If You Go:

♦ The center of town is easily accessible from the airport by a short bus or train ride. The bus and train station are within walking distance to all major sites within the city.

♦ Visit the official site of the Málaga Tourism board: www.visitcostadelsol.com

Private Full Day Tour of Malaga from Seville

About the author:

Ana Ruiz was born in Spain and is the author of two books on the subject of Spanish history and culture. Visit: ana-ruiz.weebly.com

Spanish Wine and Tapas Tasting Walking Tour in Malaga

All photos are by Ana Ruiz:

Gibralfaro Castle

Málaga Port

Plaza de Toros

Alcazába

View

Entrance to the Alcazába

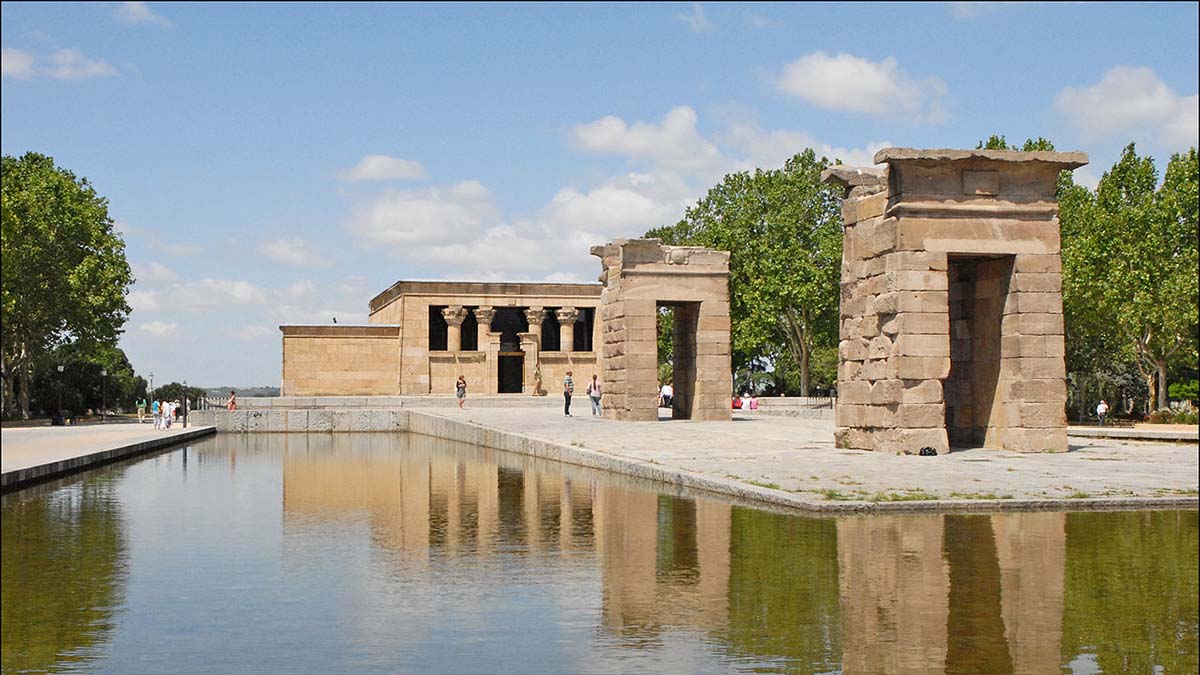

Originally, the Temple of Debod stood on the right bank of the River Nile, just above the First Cataract near Aswan, dedicated to the god Amun and the goddess Isis. In 1898, the British, who then controlled Egypt, decided to dam the Nile at Aswan, the work being completed in 1902. With typical short-sightedness, they completely disregarded the fact that some important monuments would be lost beneath the surface of the resulting lake … including the beautiful Temple of Isis on Philae Island, and the not-so-well regarded Temple of Debod nearby.

Originally, the Temple of Debod stood on the right bank of the River Nile, just above the First Cataract near Aswan, dedicated to the god Amun and the goddess Isis. In 1898, the British, who then controlled Egypt, decided to dam the Nile at Aswan, the work being completed in 1902. With typical short-sightedness, they completely disregarded the fact that some important monuments would be lost beneath the surface of the resulting lake … including the beautiful Temple of Isis on Philae Island, and the not-so-well regarded Temple of Debod nearby.

Immediately on boarding the boat above the Aswan Dam, the popular concept of modern Egypt was left behind. There’s only the boat, the lake and the temples … and tranquil, unhurried peace. On the way to Abu Simbel, the boat calls at the Kalabsha Temple site, Wadi el Seboua and the Amada Temples, all of which were rebuilt above the waters of the lake.

Immediately on boarding the boat above the Aswan Dam, the popular concept of modern Egypt was left behind. There’s only the boat, the lake and the temples … and tranquil, unhurried peace. On the way to Abu Simbel, the boat calls at the Kalabsha Temple site, Wadi el Seboua and the Amada Temples, all of which were rebuilt above the waters of the lake.

The hanging houses are the draw to this remote city but the old part of town itself is worth exploring. We take a short walk downhill from a lookout point to the Plaza Mayor where the Cuenca Cathedral is located. Dating from 1177, the building is impressive with its three arches. The Gothic Anglo-Norman façade is the only one of its kind in Spain with construction on the cathedral continuing for 300 years and never quite completed. I enjoy wandering the medieval cobblestone streets that wind past old stone houses, adorned with colorful plants spilling over the balconies and climbing up stairways.

The hanging houses are the draw to this remote city but the old part of town itself is worth exploring. We take a short walk downhill from a lookout point to the Plaza Mayor where the Cuenca Cathedral is located. Dating from 1177, the building is impressive with its three arches. The Gothic Anglo-Norman façade is the only one of its kind in Spain with construction on the cathedral continuing for 300 years and never quite completed. I enjoy wandering the medieval cobblestone streets that wind past old stone houses, adorned with colorful plants spilling over the balconies and climbing up stairways.

We spend the night at Hotel Cueva del Fraile or The Cave of Friars, an enchanting place seven kilometers up the road. This 16th century building hidden in the rugged mountains was once a monastery (for the devout), later a workhouse (for the poor) and now a luxury place of refuge (for the weary traveler). I get lost finding my room as I wander the myriad of stairs and hallways, which only adds to the charm. The structure has stayed true to its original construction and surrounds a peaceful courtyard. The rooms, with high ceilings, thick stone walls and wooden beams, have no doubt been made more comfortable since the days of the friars. Antiques depicting former times are found throughout the building. The hotel restaurant features delicious, authentic Castilian cuisine for dinner and breakfast. It’s impossible for me to resist the thick, creamy hot chocolate and chocolate filled croissants on offer. Staying at Cueva del Fraile is a memorable experience for someone with an overactive imagination. Rumour has it that there is even a hotel spook!

We spend the night at Hotel Cueva del Fraile or The Cave of Friars, an enchanting place seven kilometers up the road. This 16th century building hidden in the rugged mountains was once a monastery (for the devout), later a workhouse (for the poor) and now a luxury place of refuge (for the weary traveler). I get lost finding my room as I wander the myriad of stairs and hallways, which only adds to the charm. The structure has stayed true to its original construction and surrounds a peaceful courtyard. The rooms, with high ceilings, thick stone walls and wooden beams, have no doubt been made more comfortable since the days of the friars. Antiques depicting former times are found throughout the building. The hotel restaurant features delicious, authentic Castilian cuisine for dinner and breakfast. It’s impossible for me to resist the thick, creamy hot chocolate and chocolate filled croissants on offer. Staying at Cueva del Fraile is a memorable experience for someone with an overactive imagination. Rumour has it that there is even a hotel spook!

It had been five long years since I had participated in the program at the hotel-resort Abadía de los Templarios Hotel, a 15- to 20-minute walk from the town center of La Alberca, which is located in the western Spanish province of Salamanca amid the Sierra de Francia mountain range.

It had been five long years since I had participated in the program at the hotel-resort Abadía de los Templarios Hotel, a 15- to 20-minute walk from the town center of La Alberca, which is located in the western Spanish province of Salamanca amid the Sierra de Francia mountain range. The program officially started on Friday morning in Madrid, where some 36 participants (including myself) headed to La Alberca via a three hour-plus bus ride (or personal automobile for some Spaniards) through rolling pastures and farmlands after leaving the urban sprawl of Spain’s capital city. On the bus, Anglos and Spaniards were paired up, so the latter could begin their intensive language exposure.

The program officially started on Friday morning in Madrid, where some 36 participants (including myself) headed to La Alberca via a three hour-plus bus ride (or personal automobile for some Spaniards) through rolling pastures and farmlands after leaving the urban sprawl of Spain’s capital city. On the bus, Anglos and Spaniards were paired up, so the latter could begin their intensive language exposure. Who are these Spaniards who are there at the behest of their company or their own volition? Typically, a group is made up of professionals from various fields such as IT, production, and other fields. They are generally in their 20s or 30s, but some are older. One such Spaniard, Angel, an IT professional, was actually on his fifth program. Before taking part in Pueblo Ingles, he commented, “I didn’t understand anything,” but the intensive exposure time had increased his confidence and understanding of the language’s nuances. Another Spaniard, Rocio, who works for an energy renewal company, had studied English since high school, but remarked on her primary reason for coming, “My biggest problem is my listening. My listening is very bad.”

Who are these Spaniards who are there at the behest of their company or their own volition? Typically, a group is made up of professionals from various fields such as IT, production, and other fields. They are generally in their 20s or 30s, but some are older. One such Spaniard, Angel, an IT professional, was actually on his fifth program. Before taking part in Pueblo Ingles, he commented, “I didn’t understand anything,” but the intensive exposure time had increased his confidence and understanding of the language’s nuances. Another Spaniard, Rocio, who works for an energy renewal company, had studied English since high school, but remarked on her primary reason for coming, “My biggest problem is my listening. My listening is very bad.” Rick, a 74-year old former teacher and coach who’s taught English in China, heard about the program via word of mouth when he was in Germany (the method which has brought many Anglos to the venues). He emanated a common sentiment among the Anglos, “I want to learn more about the Spanish culture, the food. I want to help them speak English.”

Rick, a 74-year old former teacher and coach who’s taught English in China, heard about the program via word of mouth when he was in Germany (the method which has brought many Anglos to the venues). He emanated a common sentiment among the Anglos, “I want to learn more about the Spanish culture, the food. I want to help them speak English.” During one of our two-hour siestas and one of the one-to-one sessions, we took walks to the center of town, full of half-timbered houses and shops where one could obtain many things, from a can of Coca-Cola to a scarf, hat, and gloves, the latter three which my new Spanish friend found himself in need of. Our brisk walking on winding roads amid the captivating autumn foliage kept us warmer as chilled afternoons gave way to darkness. He gave me more insights on the activity since his ability to run 26 miles-plus puts my ability to run only around six miles daily to shame. As we walked back on the road leading back to the hotel through woodlands, pasture, and small farms, we could hear the soundtrack of baaing sheep and oinking pigs.

During one of our two-hour siestas and one of the one-to-one sessions, we took walks to the center of town, full of half-timbered houses and shops where one could obtain many things, from a can of Coca-Cola to a scarf, hat, and gloves, the latter three which my new Spanish friend found himself in need of. Our brisk walking on winding roads amid the captivating autumn foliage kept us warmer as chilled afternoons gave way to darkness. He gave me more insights on the activity since his ability to run 26 miles-plus puts my ability to run only around six miles daily to shame. As we walked back on the road leading back to the hotel through woodlands, pasture, and small farms, we could hear the soundtrack of baaing sheep and oinking pigs. Ignacio and I were lucky enough to catch a common spectacle of a pig that’s allowed to run freely around town to garner handouts from the 1,000-plus locals (plus tourists) as it fattens up so it can be raffled off. We saw some girls being chased by the pig after they stopped giving it handouts. Salamanca is an area where ham products, especially from the limbs of the pig, are considered delicacies.

Ignacio and I were lucky enough to catch a common spectacle of a pig that’s allowed to run freely around town to garner handouts from the 1,000-plus locals (plus tourists) as it fattens up so it can be raffled off. We saw some girls being chased by the pig after they stopped giving it handouts. Salamanca is an area where ham products, especially from the limbs of the pig, are considered delicacies. Some of the most connective moments between the participants take place during the meal times, where the table wine (lunch/dinner), tasty cuisine and conversation generously flow. Breakfasts can be a bit more laid back, given the Spanish penchant for kicking up one’s heels well into the wee hours of the morning with willing Anglos. After all, to a Spaniard, 8 p.m. is still considered “afternoon.”

Some of the most connective moments between the participants take place during the meal times, where the table wine (lunch/dinner), tasty cuisine and conversation generously flow. Breakfasts can be a bit more laid back, given the Spanish penchant for kicking up one’s heels well into the wee hours of the morning with willing Anglos. After all, to a Spaniard, 8 p.m. is still considered “afternoon.” As a seasoned veteran of this program, I couldn’t get over just how perfectly put together this group was, which is credited to the Anglos Dept. in Madrid, who do their best to match the participants up based on the application they must fill out online to be considered for a holiday that sees their room and board covered over the course of the program for their volunteer service.

As a seasoned veteran of this program, I couldn’t get over just how perfectly put together this group was, which is credited to the Anglos Dept. in Madrid, who do their best to match the participants up based on the application they must fill out online to be considered for a holiday that sees their room and board covered over the course of the program for their volunteer service.

But, how to get water supplies up there? The water from the Rio Clamores was insufficient for their needs, anyway. So, in the middle of the 1st Century AD, during the reign of the Emperor Domitian, an ambitious project was begun. A canal was dug, to bring water from the Rio Frio, 18 kilometres (12 miles) away. The valley of the Rio Clamores would be spanned by a massive aqueduct 800 metres (about 2500 feet) long and, at its highest point, reaching nearly 30 metres (100 feet) high.

But, how to get water supplies up there? The water from the Rio Clamores was insufficient for their needs, anyway. So, in the middle of the 1st Century AD, during the reign of the Emperor Domitian, an ambitious project was begun. A canal was dug, to bring water from the Rio Frio, 18 kilometres (12 miles) away. The valley of the Rio Clamores would be spanned by a massive aqueduct 800 metres (about 2500 feet) long and, at its highest point, reaching nearly 30 metres (100 feet) high.

The aqueduct was built from 25,000 stone blocks and, notwithstanding its size, no mortar at all was used in its construction. It took over fifty years to built, was completed in the early 2nd Century, by which time the Emperor Trajan had ‘taken the purple’. However, a much later folk-tale told that it had been built overnight, by the Devil himself … hence its alternative name of Puente de Diablo, or ‘Devil’s Bridge’. It’s said that the Evil One was after the soul of a local woman, to achieve which, he had to complete the bridge in a single night … in which task, he failed, because he was unable to find the last block before the sun rose.

The aqueduct was built from 25,000 stone blocks and, notwithstanding its size, no mortar at all was used in its construction. It took over fifty years to built, was completed in the early 2nd Century, by which time the Emperor Trajan had ‘taken the purple’. However, a much later folk-tale told that it had been built overnight, by the Devil himself … hence its alternative name of Puente de Diablo, or ‘Devil’s Bridge’. It’s said that the Evil One was after the soul of a local woman, to achieve which, he had to complete the bridge in a single night … in which task, he failed, because he was unable to find the last block before the sun rose.