Cape Town, South Africa

by Lynn Smith

Ask any South African which is the most beautiful city in South Africa and the answer will invariably be “Cape Town “– and with good reason. This is the city where I lived for some years and when I visit it again, I realise just how much I have missed its vibrancy. Lying beneath the shadow of the iconic Table Mountain, the city sweeps down to the Atlantic Ocean. The city has, in its four-hundred year-old history, been known by many names, including “the Fairest Cape in the entire circumference of the earth”; the “Cape of Storms”, the “Cape of Good Hope” and to many embattled and weary sailors, it was known as the “Tavern of the Seas.” To South Africans, however, Cape Town is affectionately referred to as the “Mother City” and it is the city which ex-pats dream about and return to, again and again.

The founding of the city

Cape Town was founded as a supply station in 1652, by the Dutch East India Company, under the command of Jan van Riebeeck. The company erected a fort, planted vegetable gardens, employed the indigenous people and imported Muslim slaves from Java (whose descendants are known as Cape Malays), as well as slaves from Madagascar. In time, more Dutch citizens settled in the area and soon the tiny settlement grew into a town.

In 1688, the French Huguenots, fleeing from religious persecution in France, settled in the hinterland and soon German settlers followed. In 1795 and again in 1806, the Cape came under British rule.

This brief outline of the city’s history serves to show the different nationalities, races and creeds which have populated the Cape and which, over years of integration, have contributed to Cape Town’s present varied and vibrant culture.

What to see in the city centre

Cape Town, as the Mother City, is South Africa’s seat of parliament and the impressive Houses of Parliament are situated in Government Avenue. This oak tree-lined walkway was originally part of the Dutch East India Company’s Market Gardens and several notable buildings now line its tranquil path; these include the South African Planetarium and Museum, the South African Library, the Great Synagogue and Jewish Museum and the South African National Gallery.

Cape Town, as the Mother City, is South Africa’s seat of parliament and the impressive Houses of Parliament are situated in Government Avenue. This oak tree-lined walkway was originally part of the Dutch East India Company’s Market Gardens and several notable buildings now line its tranquil path; these include the South African Planetarium and Museum, the South African Library, the Great Synagogue and Jewish Museum and the South African National Gallery.

The Castle: The Castle was built in 1666 and was both the Dutch East India Company’s governor’s residence and a fortress, and is still a working barracks today. The Castle is pentagonal in shape and the five points were named after the main titles of Wilhelm, Prince of Orange. The Castle’s thick stone walls now house three fine museums.

The Grand Parade: Originally a military parade ground, the Grand Parade is now the city’s oldest market place. Markets are held every Wednesday and Saturday mornings and just about everything and anything is sold here, including fruit, flowers, vegetables, fast food and traditional Cape Malay delicacies.

The Grand Parade: Originally a military parade ground, the Grand Parade is now the city’s oldest market place. Markets are held every Wednesday and Saturday mornings and just about everything and anything is sold here, including fruit, flowers, vegetables, fast food and traditional Cape Malay delicacies.

Green Market Square: This pleasant cobbled square is one of Cape Town’s great tourist attractions. It began in 1710 as a farmers’ market but now the square is a hive of daily activity, with hundreds of stalls selling traditional crafts, curios, clothing, books and jewellery. To rest their weary feet, tourists can refresh themselves at the many cafes and eateries and watch the passing parade go by.

District Six Museum: This small but poignant museum is dedicated to the recording of the daily lives of the people of District Six, who were forcefully removed from their homes in the 1960s and 70s. District Six was an area lying to the east of the Castle, where, for decades, people of all races, colours and nationalities had lived in harmony. In 1966, when the area was declared a “Whites only” area, under the Group Areas Act, some 150,000 people were relocated to the Cape Flats and other desolate areas several miles away from the city centre.

Interesting streets

Church Street: This is a pedestrian mall, lined with old Victorian buildings whose wrought-iron balconies shade the sidewalks packed with antique bric-a-brac. Many a bargain can be picked up, after some clever haggling.

Long Street: This 300 year-old street showcases buildings which are a hotch-potch of architectural styles – Victorian, Art Nouveau, Georgian and Cape Malay styles, all rub shoulders with each other. These delightful old edifices accommodate pubs and book shops, as well as the famous Long Street Baths, comprising a swimming pool, steam rooms and Turkish baths.

Wale Street: Here one finds St George’s Mall, a pedestrian area lined with shops and bistros, where buskers, musicians, traditional dancers and vendors all ply their various talents. The Stuffaford’s Town Square is a shopper’s paradise, with modern retail stores comparable to any of those found in Europe’s fashionable capitals. At the top of the Mall, is St George’s Anglican Cathedral, a Gothic masterpiece, designed by Sir Herbert Baker in 1897.

Adderley Street: Adderley Street is Cape Town’s main street and CBD. The street has a fine statue of Vasco da Gama who sailed past the Cape peninsula on his way to India in 1488.

Table Mountain

A visit to Cape Town would not be complete without a visit to Table Mountain. This landmark is 1082 metres high and from the central plateau (the table top) fantastic views extend for miles in all directions. The mountain top can be reached by walking, climbing or by cable car – the cable car, however, does not operate in inclement weather.

A visit to Cape Town would not be complete without a visit to Table Mountain. This landmark is 1082 metres high and from the central plateau (the table top) fantastic views extend for miles in all directions. The mountain top can be reached by walking, climbing or by cable car – the cable car, however, does not operate in inclement weather.

The Victoria and Albert Waterfront

The Victoria and Albert Waterfront is a series of converted warehouses which comprise cinemas, restaurants, upmarket shopping stores and all-night bars and party venues. There is also an amphitheatre which hosts a variety of popular entertainers.

The Pier Head area contains the Victoria museum ship – a replica of an old-time sailing vessel; for children, the Market Square has a traditional carousel and from the Waterfront, one can also take a pleasure cruise around Table Bay.

Robben Island

A 45 minute sea-trip takes one to Robben Island, where political prisoners were held, the most famous of whom was Nelson Mandela, who spent 28 years on the island. Tours are available round the island where Mandela’s prison cell, the lime quarries, the lighthouse, the WWII bunkers and the Garrison church can be visited. The island is a national heritage site and much is being done to protect its natural flora and fauna.

Other sights

Other sights

Rhodes Memorial: Cecil John Rhodes was a key figure in South Africa in the late 19th century – his elaborate, colonnaded memorial is set on the slopes of Table Mountain.

Kirstenbosch: The National Botanical Gardens at Kirstenbosch are known throughout the world for their incredible variety of plants. Several trails through the gardens lead up the slopes of Table Mountain and during summer months, open-air recitals are held amidst the colourful plants and well-tended lawns.

Beaches

Cape Town has a plethora of beaches which stretch right round the peninsula. The most popular ones nearest to the city are the trendy beaches on the Atlantic seaboard side. These are:

Sea Point, with its promenade and several tidal pools, including a mens-only nudist pool.

Clifton Beach and Bantry Bay Beaches – two glamourous beaches overlooked by Cape Town’s two most desirable residential areas, built on the steep mountain side. This piece of coastline, with its exceptional and expensive real estate, is known as millionaire’s mile.

Nightlife

Pubs, bars and nightclubs, catering for all tastes, are plentiful and scattered throughout the city and its surrounds. There are British and Irish pubs as well as the local shebeens.

Theatres and Music

Cape Town has four theatres which regularly put on a variety of productions. All types of music tastes are catered for – classical, jazz, traditional and rock. Concerts are well-attended and one is well-advised to book.

Food

Cape Town is famous for its seafood and the best seafood restaurants are located along the beachfront and at the Waterfront, where traditional Cape Malay and African dishes can also be experienced.

Several upmarket restaurants in the city centre pride themselves on their fine dining menus. There are also numerous popular fast food, chain and franchise outlets, as well as Chinese, Italian and other national-type eateries to choose from.

Annual events

Some of the most popular yearly events are:

The J & B Metropolitan Handicap: The prestigious horse race held at Kenilworth race course.

The Two Oceans Marathon: The marathon race round the peninsula which attracts athletes from all over the world.

The Cape Argus Cycle Tour: A gruelling cycle race round the peninsula.

The Rothman’s Week Yacht Race: A week-long yacht race round Table Bay, with yachts from all over the world competing.

The Cape Town International Jazz Festival: This is the largest jazz festival in Africa and last year it attracted a crowd of some 34,000 concert-goers. The jazz festival is renowned throughout the world and many of the most famous jazz artists have showcased their talents here.

Cape Town has so much to offer – beautiful scenery, pristine beaches, fine food and wines, interesting events – but most of all, it is its colourful and varied population which gives the city its vibrant and interesting culture.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that Cape Town was voted the best tourist destination in 2014, both by Britain’s “The Guardian” newspaper and America’s “The New York Times.”

Private Tour: Cape Town City and Table Mountain from Cape Town

If You Go:

♦ There are local and international flights daily to and from Cape Town. The city is also an important port of call for many of the cruise ships plying the Indian Ocean route. Car hire is available from the airport and harbour terminal.

♦ Getting around the city: The city is best explored on foot. There are guided walking tours but a good map is all that one really needs. There is a good central bus service and numerous taxis and car hire firms. An excellent train service runs to all the suburban stations.

♦ Be prepared to walk –take suntan lotion with you, as the sun can be quite fierce. Don’t forget to take your camera – Cape Town is one of the most photogenic places in the world!

♦ The best time to visit is from November to April, which are Cape Town’s summer months and the height of the tourist season. Winter months (May – October) are often very wet and cold.

♦ Accommodation is available to suit all pockets. The city centre can be expensive, but the nearby suburbs offer reasonable rates.

Full-Day Wildlife Safari, Craft Beer and Wine Tasting Tour from Cape Town

About the author:

Lynn is a retired librarian who lives in Durban, South Africa. She lived in London for some time many years ago and has returned to visit several times in the past few years. Her last visits overseas were to Eastern Europe where she fell in love with Prague and Budapest. When not travelling, Lynn enjoys writing articles for the internet and does freelance editing and proof-reading. She is a keen gardener and shares her home with her six beloved cats.

Photo credits:

Camps Bay Cape Town by Jaman Asad on Unsplash

Houses of Parliament by I, PhilippN / CC BY-SA

Grand Parade by yeowatzup from Göttingen, Germany / CC BY

Table Mountain by Ulrike Mai from Pixabay

The project was overseen by the South Africa Development Agency. “The community is very happy with the result,” says Thanduxolo Ntoyi, an assistant development manager at the agency. The community was “very involved” with the street and its transformation from the beginning.

The project was overseen by the South Africa Development Agency. “The community is very happy with the result,” says Thanduxolo Ntoyi, an assistant development manager at the agency. The community was “very involved” with the street and its transformation from the beginning. Outside the house stands a large metal outline of two bull heads, entitled The Nobel Laureates. The title refers to the fact that on the corner of Vilakazi and Ngakane Streets, a short distance away, is the Soweto home of the Anglican Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, who, like Mandela, was the recipient of a Nobel Peace Prize. The bulls look down the road, decisive and eye-catching, leaving no doubt as to the strength of the two personalities they represent. Around the corner in Moema Street is another metal depiction, this time of schoolchildren facing a policeman with a growling dog. It’s a reference to the confrontation on 16 June 1976 when hundreds of black school children were protesting the imposition of European Afrikaans in schools, when they were met by the brutality of the colonial police.

Outside the house stands a large metal outline of two bull heads, entitled The Nobel Laureates. The title refers to the fact that on the corner of Vilakazi and Ngakane Streets, a short distance away, is the Soweto home of the Anglican Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, who, like Mandela, was the recipient of a Nobel Peace Prize. The bulls look down the road, decisive and eye-catching, leaving no doubt as to the strength of the two personalities they represent. Around the corner in Moema Street is another metal depiction, this time of schoolchildren facing a policeman with a growling dog. It’s a reference to the confrontation on 16 June 1976 when hundreds of black school children were protesting the imposition of European Afrikaans in schools, when they were met by the brutality of the colonial police.

At the start of Vilakazi Street, where it intersects with Khumalo Street, is another magnificent artwork. Eight huge, grey hands spell “Vilakazi” in sign language. The hands are big and bold, but accessible to residents – they have become play objects, with children taking time out to climb on them. Other art includes two murals – one depicts the scene of June 1976, with police and their vans, and placard-carrying schoolchildren. And then there are the mosaics, livening up several concrete benches on the corner of Moema Street; down Vilakazi Street are mosaic strips of paving. On the corner of Vilakazi and Ngakane streets is a row of bollards with decorative wooden heads. Vilakazi Street is indeed a different place.

At the start of Vilakazi Street, where it intersects with Khumalo Street, is another magnificent artwork. Eight huge, grey hands spell “Vilakazi” in sign language. The hands are big and bold, but accessible to residents – they have become play objects, with children taking time out to climb on them. Other art includes two murals – one depicts the scene of June 1976, with police and their vans, and placard-carrying schoolchildren. And then there are the mosaics, livening up several concrete benches on the corner of Moema Street; down Vilakazi Street are mosaic strips of paving. On the corner of Vilakazi and Ngakane streets is a row of bollards with decorative wooden heads. Vilakazi Street is indeed a different place. This is another landmark that enriches Vilakazi Street. This memorial has been completed, and it remembers the 15-year-old boy who was the first to be shot on 16 June 1976 riots against the white apartheid government. On the corner of Klipspruit Valley and Khumalo roads is a bridge where Hastings Ndlovu was shot by the police. He was rushed to Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital – one of the world’s biggest hospitals- where he died of the head wound.

This is another landmark that enriches Vilakazi Street. This memorial has been completed, and it remembers the 15-year-old boy who was the first to be shot on 16 June 1976 riots against the white apartheid government. On the corner of Klipspruit Valley and Khumalo roads is a bridge where Hastings Ndlovu was shot by the police. He was rushed to Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital – one of the world’s biggest hospitals- where he died of the head wound.

During the two years since Darren’s first trip to Uganda, he has pulled together this disparate team to partner with local youth and run three-day camps for young children. We are a typical Vancouver mix: five Chinese, three Phillipino and three Caucasian. The youngest are fifteen and I am the oldest at 71.

During the two years since Darren’s first trip to Uganda, he has pulled together this disparate team to partner with local youth and run three-day camps for young children. We are a typical Vancouver mix: five Chinese, three Phillipino and three Caucasian. The youngest are fifteen and I am the oldest at 71. “Here we are,” Darren shouts, as the Ipsum swerves hard right and climbs the short distance to the Albertine Graben Tourist Resort Hotel, where Tyler and Michelle have booked rooms for us. It’s colonial style with white pillared colonnades along both floors. The roof is peaked with ochre dormers.

“Here we are,” Darren shouts, as the Ipsum swerves hard right and climbs the short distance to the Albertine Graben Tourist Resort Hotel, where Tyler and Michelle have booked rooms for us. It’s colonial style with white pillared colonnades along both floors. The roof is peaked with ochre dormers. Fields of cabbage, plantain and potatoes blanket the valley. We leave the road at Bubaale, a small village with just a few tin-roofed mud-brick houses and turn onto a narrow, dirt road that winds upward through the terraced hillside. During daylight, people live outdoors. Women in patterned dresses and head wraps walk to the creek or the village spigot for water. Even small children carry a yellow jerry can.

Fields of cabbage, plantain and potatoes blanket the valley. We leave the road at Bubaale, a small village with just a few tin-roofed mud-brick houses and turn onto a narrow, dirt road that winds upward through the terraced hillside. During daylight, people live outdoors. Women in patterned dresses and head wraps walk to the creek or the village spigot for water. Even small children carry a yellow jerry can. The boys entertain us with African dance, songs and feats of strength: chins, pushups and backflips. They tell me that their tribe, the Bukiga, are strong men and if you hire them, they work hard.

The boys entertain us with African dance, songs and feats of strength: chins, pushups and backflips. They tell me that their tribe, the Bukiga, are strong men and if you hire them, they work hard. Tyler parks in front of the restaurant beside a hitching post. The server takes us through a room containing four tables and a bar. Behind that, we step down to a sunken floor and crowd around a table with bench seats. A steamy, pasty smell emanates from the courtyard behind the restaurant where a woman stirs a large pot of something sticky and grey-white. The shed behind her is cluttered with cooking implements and sacks of corn meal and potatoes. Another woman washes clothes in a deep metal basin.

Tyler parks in front of the restaurant beside a hitching post. The server takes us through a room containing four tables and a bar. Behind that, we step down to a sunken floor and crowd around a table with bench seats. A steamy, pasty smell emanates from the courtyard behind the restaurant where a woman stirs a large pot of something sticky and grey-white. The shed behind her is cluttered with cooking implements and sacks of corn meal and potatoes. Another woman washes clothes in a deep metal basin.

The full-service, island resort accommodates tourists in view bungalows or hotel suites. The open air restaurant and bar provide quality meals and drinks, including local specialties such as Louisiana red swamp crayfish, cooked with organic herbs and spices. They are not imported, but fresh from the lake which was stocked in the Seventies.

The full-service, island resort accommodates tourists in view bungalows or hotel suites. The open air restaurant and bar provide quality meals and drinks, including local specialties such as Louisiana red swamp crayfish, cooked with organic herbs and spices. They are not imported, but fresh from the lake which was stocked in the Seventies. We had invited the village of Bubaale to come to Akanyijuka Primary School for a carnival on the last Saturday. A large, white gazebo is raised and a loud speaker system prepared for speeches. Hundreds line up for poshoe and beans, but just as the last few are served, a torrential storm drives everyone into the buildings or away to their homes, ending the carnival. We crowd into one of the old wood-plank, school classrooms and bid a tearful goodbye to our strong, Buchiga trainees.

We had invited the village of Bubaale to come to Akanyijuka Primary School for a carnival on the last Saturday. A large, white gazebo is raised and a loud speaker system prepared for speeches. Hundreds line up for poshoe and beans, but just as the last few are served, a torrential storm drives everyone into the buildings or away to their homes, ending the carnival. We crowd into one of the old wood-plank, school classrooms and bid a tearful goodbye to our strong, Buchiga trainees.

The grip of Roman imperialism was nowhere so dominant in Tunisia as in the city of Carthage – Tunisia’s most famous site of ancient Roman ruins. Although the Romans initially ravaged and destroyed much of the city upon invasion, they subsequently rebuilt it in the style of Rome. Its favourable position and two harbours made it a grand hubbub of expensive, imported goods.

The grip of Roman imperialism was nowhere so dominant in Tunisia as in the city of Carthage – Tunisia’s most famous site of ancient Roman ruins. Although the Romans initially ravaged and destroyed much of the city upon invasion, they subsequently rebuilt it in the style of Rome. Its favourable position and two harbours made it a grand hubbub of expensive, imported goods. In the North West of Tunisia, the small town of Dougga stands as an impressively intact testimony to the Roman rulers that once dominated here (though the remaining monuments are by no means solely Roman in origin). The town is thought to have been founded during the reign of Julius Caesar, and became a small, prosperous town complete with theatres, baths and roman villas in the style for which they have becomes so famous. For those visiting the country today, this is a must-see area.

In the North West of Tunisia, the small town of Dougga stands as an impressively intact testimony to the Roman rulers that once dominated here (though the remaining monuments are by no means solely Roman in origin). The town is thought to have been founded during the reign of Julius Caesar, and became a small, prosperous town complete with theatres, baths and roman villas in the style for which they have becomes so famous. For those visiting the country today, this is a must-see area. Though not a hotbed of archaeological sites in itself, the coastal town of Sousse hosts an incredible array of Roman mosaics, rescued from the various excavated sites around the country. Displayed in its Archaeological museum, the collection isn’t overwhelmingly large, but is one of the bigger collections of authentic mosaics in Tunisia.

Though not a hotbed of archaeological sites in itself, the coastal town of Sousse hosts an incredible array of Roman mosaics, rescued from the various excavated sites around the country. Displayed in its Archaeological museum, the collection isn’t overwhelmingly large, but is one of the bigger collections of authentic mosaics in Tunisia.

Emperor Hadrian granted Roman citizenship to the inhabitants of this town, perhaps because of the wealth of grandeur there. The archaeology unearthed is testament to the many wealthy homes and residential areas.

Emperor Hadrian granted Roman citizenship to the inhabitants of this town, perhaps because of the wealth of grandeur there. The archaeology unearthed is testament to the many wealthy homes and residential areas. In El Jem sat the centrepiece of the reputable area once known as Thysdrus, the second most important Roman municipality in Africa after Carthage. The magnificent amphitheatre, though now slightly dilapidated, once seated an enormous 43,000 spectators (the 02 arena in London holds under half of that, with 20,000 seats). This makes it the third largest amphitheatre to have existed during Roman rule.

In El Jem sat the centrepiece of the reputable area once known as Thysdrus, the second most important Roman municipality in Africa after Carthage. The magnificent amphitheatre, though now slightly dilapidated, once seated an enormous 43,000 spectators (the 02 arena in London holds under half of that, with 20,000 seats). This makes it the third largest amphitheatre to have existed during Roman rule.

I was delighted to wake up the next morning to a clear view of the Rock of Gibraltar from my window and knowing that I would be spending the day in Morocco. Arriving at the Port of Algeciras just 100 feet across the hotel, I was instructed to wait for my guide as soon as I off-boarded the ferry in Ceuta. Ceuta is one of the two Spanish autonomous communities in North Africa along with Melilla located about 390 further east. Ferries also depart to Melilla on the northern coast of Africa from the ports of Malaga or Almeria that can take over 9 hours across the Alborán Sea.

I was delighted to wake up the next morning to a clear view of the Rock of Gibraltar from my window and knowing that I would be spending the day in Morocco. Arriving at the Port of Algeciras just 100 feet across the hotel, I was instructed to wait for my guide as soon as I off-boarded the ferry in Ceuta. Ceuta is one of the two Spanish autonomous communities in North Africa along with Melilla located about 390 further east. Ferries also depart to Melilla on the northern coast of Africa from the ports of Malaga or Almeria that can take over 9 hours across the Alborán Sea.

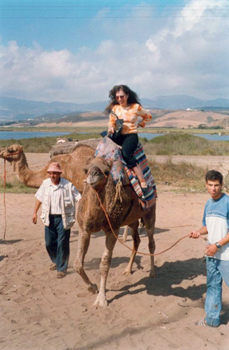

I looked at one of the passengers with a puzzled look that was immediately reciprocated. Moments later the mini bus suddenly pulled off to the side of the road where locals were offering camel rides for one Euro. At first I hesitated, but it took just six words from one of the couples to get me on top of that camel, “You’ll regret it if you don’t!”

I looked at one of the passengers with a puzzled look that was immediately reciprocated. Moments later the mini bus suddenly pulled off to the side of the road where locals were offering camel rides for one Euro. At first I hesitated, but it took just six words from one of the couples to get me on top of that camel, “You’ll regret it if you don’t!” After passing through the chaos of the open air food market, we arrived at the fabric and textile market. On display were hundreds of thick fabrics of the most vivid colors for sale hand woven by local Berber women. Lost in my world I was when suddenly one such woman stopped me and grabbed me by my shoulders.

After passing through the chaos of the open air food market, we arrived at the fabric and textile market. On display were hundreds of thick fabrics of the most vivid colors for sale hand woven by local Berber women. Lost in my world I was when suddenly one such woman stopped me and grabbed me by my shoulders. The next stop was the carpet demonstration. Here, we were led into a showroom where traditional mint tea was offered while we waited for the ‘show’ to begin. One by one, they rolled out these works of art, each more exquisite and intricate than the last. By the time the demonstration was over, the prices were greatly reduced. No-one in our group had any intention of purchasing a rug yet the vendor instructed us to individually say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to every single carpet that they had rolled out. After these very uncomfortable minutes were over, we quickly departed leaving the disgruntled vendors mumbling to themselves while they hastily rolled back the carpets.

The next stop was the carpet demonstration. Here, we were led into a showroom where traditional mint tea was offered while we waited for the ‘show’ to begin. One by one, they rolled out these works of art, each more exquisite and intricate than the last. By the time the demonstration was over, the prices were greatly reduced. No-one in our group had any intention of purchasing a rug yet the vendor instructed us to individually say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to every single carpet that they had rolled out. After these very uncomfortable minutes were over, we quickly departed leaving the disgruntled vendors mumbling to themselves while they hastily rolled back the carpets. We were now on our way to the spice and pharmacy market; a welcomed relief as the ‘pharmacist’ dressed in a white lab coat was quite the comedian. The small room resembled a medieval apothecary with all sorts of jars and containers of all colors, shapes, and sizes filled with oils, fragrances, creams, herbal remedies, spices, and teas that cured everything from anxiety to hangovers. The pharmacist/comedian demonstrated the wonders of the selected products that we smelled, rubbed on our skin, or whatever we were instructed to do. Each of us bought a few cosmetic and medicinal items as we did not want to offend this vendor as well.

We were now on our way to the spice and pharmacy market; a welcomed relief as the ‘pharmacist’ dressed in a white lab coat was quite the comedian. The small room resembled a medieval apothecary with all sorts of jars and containers of all colors, shapes, and sizes filled with oils, fragrances, creams, herbal remedies, spices, and teas that cured everything from anxiety to hangovers. The pharmacist/comedian demonstrated the wonders of the selected products that we smelled, rubbed on our skin, or whatever we were instructed to do. Each of us bought a few cosmetic and medicinal items as we did not want to offend this vendor as well. Next on our busy itinerary was a one hour bus ride to Tangier, the “Gateway to Africa” founded in the 5th century BCE. I was especially excited as it was here where my grandparents worked, met and married nearly a century ago. Upon arrival, Mohammed took us through another quick walk through the zigzag alleys and corners of the medina to the Mamounia Palace Restaurant. The restaurant, filled to capacity with other tour groups, was lavishly decorated with crimson and golden tapestries, deep red tablecloths, and plush sofas. I immediately took a photo of the lovely view from the balcony window.

Next on our busy itinerary was a one hour bus ride to Tangier, the “Gateway to Africa” founded in the 5th century BCE. I was especially excited as it was here where my grandparents worked, met and married nearly a century ago. Upon arrival, Mohammed took us through another quick walk through the zigzag alleys and corners of the medina to the Mamounia Palace Restaurant. The restaurant, filled to capacity with other tour groups, was lavishly decorated with crimson and golden tapestries, deep red tablecloths, and plush sofas. I immediately took a photo of the lovely view from the balcony window. We each took turns posing with the musicians for a small fee and the quartet began to play traditional Moroccan music with such instruments as the hand drum (darbuka), lute (oud), tambourine (riq), and violin (rababa). Moments later, our lunch was served consisting of lentil soup, a briouat or meat-filled pastry, hummus and bread, chicken with couscous and vegetables, followed by a slice of melon with mint tea for dessert. Halfway through the meal, a blonde belly dancer in a purple and gold costume whirled her way into the center of the room and entertained us to the lively music of the band.

We each took turns posing with the musicians for a small fee and the quartet began to play traditional Moroccan music with such instruments as the hand drum (darbuka), lute (oud), tambourine (riq), and violin (rababa). Moments later, our lunch was served consisting of lentil soup, a briouat or meat-filled pastry, hummus and bread, chicken with couscous and vegetables, followed by a slice of melon with mint tea for dessert. Halfway through the meal, a blonde belly dancer in a purple and gold costume whirled her way into the center of the room and entertained us to the lively music of the band. Shortly after our lunch, were once again whisked to the bus and into a department-sized store in the center of Tangier selling the finest Moroccan handicrafts, gifts, furnishings, rugs, leather goods, pottery, clothing, jewelry, and quality souvenirs available. We were told that we had a half hour to shop and encouraged to purchase as much as we could. This would be the last stop on our itinerary and right on schedule, after 30 minutes, we made our way back to the bus.

Shortly after our lunch, were once again whisked to the bus and into a department-sized store in the center of Tangier selling the finest Moroccan handicrafts, gifts, furnishings, rugs, leather goods, pottery, clothing, jewelry, and quality souvenirs available. We were told that we had a half hour to shop and encouraged to purchase as much as we could. This would be the last stop on our itinerary and right on schedule, after 30 minutes, we made our way back to the bus.