Orihuela, Spain

by Darlene Foster

We enter the historic part of Orihuela City by the town hall and are immediately transported back in time. The town is decked out medieval style. A feast for all senses, we are greeted by colourful tents, the smells of exotic spices, teas, paellas, fresh baked bread, pastries, and goat milk soap. The vendors and entertainers dressed in medieval garb add to the ambiance.

We wander aimlessly around the numerous stalls of artisans, bakers, butchers, fishmongers, drummers, acrobats, camels, ponies and much more scattered throughout the town. Every corner we round, we see new and exciting sites. A troupe of drummers march down a street and stop at the cathedral to put on a show. Knights Templar serve special cakes. Bread is baked on site in ancient wood-fired ovens. Belly dancers greet us on a side street. A camel tender gives rides to children while an ancient merry-go-round and a puppet show, including a dragon, delight the little ones. It is truly a family event with all ages taking in the festivities.

We wander aimlessly around the numerous stalls of artisans, bakers, butchers, fishmongers, drummers, acrobats, camels, ponies and much more scattered throughout the town. Every corner we round, we see new and exciting sites. A troupe of drummers march down a street and stop at the cathedral to put on a show. Knights Templar serve special cakes. Bread is baked on site in ancient wood-fired ovens. Belly dancers greet us on a side street. A camel tender gives rides to children while an ancient merry-go-round and a puppet show, including a dragon, delight the little ones. It is truly a family event with all ages taking in the festivities.

The historic town of Orihuela dates back to the sixth century where the foundations were laid by the Romans. It features Arabian and European cultures that have lived here together over the many centuries. The Arabian coffee tents are so authentic, I feel like I am in the Middle East.

We stroll aimlessly around the various tents and stalls, tempted by the food for offer until we stop for a relaxing tea and delicious tapas. For dessert we share a bag of warm, freshly made churros sprinkled with sugar. Nibbling on our tasty treats, we wander some more, stopping to watch a sculpture at work and a blacksmith create a sword. Along one avenue is a display of birds of prey with an authentic falconer present. He allows a young boy to put on a glove and hold a falcon on his wrist. The smile never leaves this young man´s face. I particularly like the owls as each one seems to have a personality of its own.

We stroll aimlessly around the various tents and stalls, tempted by the food for offer until we stop for a relaxing tea and delicious tapas. For dessert we share a bag of warm, freshly made churros sprinkled with sugar. Nibbling on our tasty treats, we wander some more, stopping to watch a sculpture at work and a blacksmith create a sword. Along one avenue is a display of birds of prey with an authentic falconer present. He allows a young boy to put on a glove and hold a falcon on his wrist. The smile never leaves this young man´s face. I particularly like the owls as each one seems to have a personality of its own.

Orihuela City sits at the base of the Sierra de Orihuela Mountains in the province of Alicante, Spain. As much as I enjoy the market, I am also taken by the historic buildings such as the sixteenth century Santo Domingo Diocese College with its wonderful renaissance doorways and serene courtyard. Another interesting building is the Salvador and Santa Maria Cathedral, built on the remains of the old Moorish mosque at the end of the thirteenth century. This building also has an amazing doorway and bell tower. Wandering down a side street we find more interesting doorways and an old mosque. There is no end to the treasures we find.

This three day event is held every year at the beginning of February. You really must spend an entire day to take in all the flavours, textures, scents, sights and sounds.

If You Go:

Orihuela City is an interesting pace to visit at any time of the year. It is situated 52 kilometres southwest of Alicante airport on the N340. It is only 20 kilometres from the many beaches of Orihuela Costa. There are buses available for the medieval market from a number of locations.

Low Cost Private Transfer From Alicante Airport to Orihuela City – One Way

About the author:

Darlene Foster is a dedicated writer and traveler. She is the author of a series of books featuring Amanda, a spunky young girl who loves to travel to interesting places such as the United Arab Emirates, Spain, England and Alberta, where she always has an adventure. Darlene divides her time between the west coast of Canada and the Costa Blanca of Spain. www.darlenefoster.ca

All photos are by Darlene Foster.

The walls and the iron grey Gothic cathedral are the ‘stones’ and Santa Teresa is the ‘saint’. My incentive to finally make the journey was the fact that this March saw her 500th anniversary. What better reason to travel than to follow in the footsteps of one of the foremost and most proliferate writers of Christian mysticism and the founder of the Discalced Carmelite nuns. An added bonus is the fact that Teresa would also have seen and been able to walk along the walls which encircle the old town of Avila with a perimeter of 2,516 kilometers.

The walls and the iron grey Gothic cathedral are the ‘stones’ and Santa Teresa is the ‘saint’. My incentive to finally make the journey was the fact that this March saw her 500th anniversary. What better reason to travel than to follow in the footsteps of one of the foremost and most proliferate writers of Christian mysticism and the founder of the Discalced Carmelite nuns. An added bonus is the fact that Teresa would also have seen and been able to walk along the walls which encircle the old town of Avila with a perimeter of 2,516 kilometers. I had chosen a small hotel which was adjacent to one of the gates, so I just dropped my bags and went out to explore. Directly in front of me was Plaza de Santa Teresa with a church bearing her name and a small museum.

I had chosen a small hotel which was adjacent to one of the gates, so I just dropped my bags and went out to explore. Directly in front of me was Plaza de Santa Teresa with a church bearing her name and a small museum.

Poverty, serenity, mental prayer and meditation practices are the keystones of Teresa’s writings. She finally entered a Carmelite convent and was appalled to find that the nuns of her times adhered to none of them. Life in a convent in the 16th century was very worldly and she decided to change that and bring the order back to what it was intended to be.

Poverty, serenity, mental prayer and meditation practices are the keystones of Teresa’s writings. She finally entered a Carmelite convent and was appalled to find that the nuns of her times adhered to none of them. Life in a convent in the 16th century was very worldly and she decided to change that and bring the order back to what it was intended to be. The month of October is dedicated to a festival of Santa Teresa, with processions , concerts and other festivities. As I found out when walking further into town, sweets form a part of the cult of Santa Teresa. To this day, the nuns produce Yemas de Santa Teresa, a sort of biscuit made from egg yolk and sugar and little chocolate nuns making the yemas are displayed in every patisserie. They make a nice souvenir and gift.

The month of October is dedicated to a festival of Santa Teresa, with processions , concerts and other festivities. As I found out when walking further into town, sweets form a part of the cult of Santa Teresa. To this day, the nuns produce Yemas de Santa Teresa, a sort of biscuit made from egg yolk and sugar and little chocolate nuns making the yemas are displayed in every patisserie. They make a nice souvenir and gift.

by Ellen Johnston

by Ellen Johnston  Of course, to say that Granada is the home of Flamenco is a very controversial thing. Seville also claims this title, and competition between the two cities is fierce. But whatever your opinion on the matter, it is undeniable that Flamenco inhabits every nook and cranny of this place, from the street corners where buskers play for spare change, to the smoke-filled caves of Sacromonte (the traditional Gypsy quarter), to the grand stages that draw large tourist crowds.

Of course, to say that Granada is the home of Flamenco is a very controversial thing. Seville also claims this title, and competition between the two cities is fierce. But whatever your opinion on the matter, it is undeniable that Flamenco inhabits every nook and cranny of this place, from the street corners where buskers play for spare change, to the smoke-filled caves of Sacromonte (the traditional Gypsy quarter), to the grand stages that draw large tourist crowds. When García Lorca wrote about his Granada, he was keenly aware of living in a forgotten, lost world, not only inhabited by Gypsies, but also by those who came before. When the Moors ruled Spain, a policy of tolerance called La Convivencia (the Coexistence) led to the creation and preservation of a very multicultural society. While Spanish tradition sees this era as a dark period before the glorious Catholic Reconquest, Lorca felt quite the opposite. For him it was a Golden Age of reason and beauty, lost. However, traces of this world still remain in Granada to this day – in the terraced gardens of the Jewish quarter, in the winding narrow streets of the Albayzín (the Muslim quarter), and in the many churches that were once mosques (and mosques that were once churches) sprinkled throughout the city.

When García Lorca wrote about his Granada, he was keenly aware of living in a forgotten, lost world, not only inhabited by Gypsies, but also by those who came before. When the Moors ruled Spain, a policy of tolerance called La Convivencia (the Coexistence) led to the creation and preservation of a very multicultural society. While Spanish tradition sees this era as a dark period before the glorious Catholic Reconquest, Lorca felt quite the opposite. For him it was a Golden Age of reason and beauty, lost. However, traces of this world still remain in Granada to this day – in the terraced gardens of the Jewish quarter, in the winding narrow streets of the Albayzín (the Muslim quarter), and in the many churches that were once mosques (and mosques that were once churches) sprinkled throughout the city. It’s not worth dwelling too much on the Alhambra, as every guide book on Granada mentions it, and it’s an absolute must-see whether you’re following in the footsteps of García Lorca or not. However, it is important to understand that it is one of the greatest examples of medieval Islamic architecture in the world, and that the soul of the city is inherent within its walls: in all that was lost, in all that was built over, and in the mysterious, magical energy that remains, nonetheless. In fact, García Lorca was so moved by the energy of this place that he chose it to be the staging ground for the Concurso de Cante Jondo, a contest of the Deep Song that he helped to organize in 1922. If you visit Granada in June, you can catch a glimpse of this contest’s modern descendant: the International Festival of Music and Dance, which features music concerts, dances and traditional Flamenco events, all on the grounds of the ancient red fortress.

It’s not worth dwelling too much on the Alhambra, as every guide book on Granada mentions it, and it’s an absolute must-see whether you’re following in the footsteps of García Lorca or not. However, it is important to understand that it is one of the greatest examples of medieval Islamic architecture in the world, and that the soul of the city is inherent within its walls: in all that was lost, in all that was built over, and in the mysterious, magical energy that remains, nonetheless. In fact, García Lorca was so moved by the energy of this place that he chose it to be the staging ground for the Concurso de Cante Jondo, a contest of the Deep Song that he helped to organize in 1922. If you visit Granada in June, you can catch a glimpse of this contest’s modern descendant: the International Festival of Music and Dance, which features music concerts, dances and traditional Flamenco events, all on the grounds of the ancient red fortress.

While the Alhambra is the most significant and audacious example of the ancient cultural mix that García Lorca so revered, there are many much smaller, simpler pleasures that tell the same story. Among the lovelier of the city’s customs is the tradition of convent sweets, baked good that are made and sold by cloistered nuns. The recipes are as old as the city itself, influenced by ingredients brought by foreign invaders: almonds, spices and citrus peels, among others. Because the nuns are cloistered, an unusual retail system prevails in order to actually buy these sweets. Upon arrival at a convent (of which there are many sprinkled throughout the city), you are greeted by a buzzer, a price list and a lazy Susan. When you’ve made your order, the lazy Susan spins, revealing tasty treats. An honor system prevails, and you pay the same way, via another spin.

While the Alhambra is the most significant and audacious example of the ancient cultural mix that García Lorca so revered, there are many much smaller, simpler pleasures that tell the same story. Among the lovelier of the city’s customs is the tradition of convent sweets, baked good that are made and sold by cloistered nuns. The recipes are as old as the city itself, influenced by ingredients brought by foreign invaders: almonds, spices and citrus peels, among others. Because the nuns are cloistered, an unusual retail system prevails in order to actually buy these sweets. Upon arrival at a convent (of which there are many sprinkled throughout the city), you are greeted by a buzzer, a price list and a lazy Susan. When you’ve made your order, the lazy Susan spins, revealing tasty treats. An honor system prevails, and you pay the same way, via another spin.

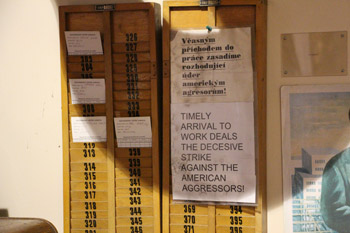

In order to understand Prague’s revolution, one must understand what led to it, and there’s nothing better than the Communism museum for this. The museum is full of exhibits of life under the regime, though one gets the feeling that it’s rather tongue in cheek, given the postcards devoted to life under Communism – “You couldn’t get laundry detergent, but you could get your brainwashed”; “It was a time of happy, shiny people. The shiniest were in the uranium mines.” That was my first clue that music had something to do with all of this dark history.

In order to understand Prague’s revolution, one must understand what led to it, and there’s nothing better than the Communism museum for this. The museum is full of exhibits of life under the regime, though one gets the feeling that it’s rather tongue in cheek, given the postcards devoted to life under Communism – “You couldn’t get laundry detergent, but you could get your brainwashed”; “It was a time of happy, shiny people. The shiniest were in the uranium mines.” That was my first clue that music had something to do with all of this dark history. The Prague Spring came about in 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubcek was elected as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Reforms by Dubcek were intended to grant more rights to citizens, including loosening strict restrictions on media – for the first time, young Czechs could listen to the Beatles on the radio. That was one thing that surprised me as I wandered the Communist museum – how willing locals were to seek out their favorite rock groups from America, buying records on vinyl from Western Europe and listening to them in secret.

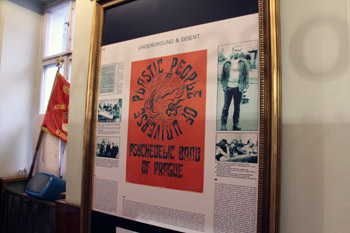

The Prague Spring came about in 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubcek was elected as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Reforms by Dubcek were intended to grant more rights to citizens, including loosening strict restrictions on media – for the first time, young Czechs could listen to the Beatles on the radio. That was one thing that surprised me as I wandered the Communist museum – how willing locals were to seek out their favorite rock groups from America, buying records on vinyl from Western Europe and listening to them in secret. Inspired by the Velvet Underground, a group of Prague natives formed a band called the Plastic People of the Universe, just a month after the Prague Spring was suppressed by Warsaw Pact troops and just after Jan Palach, a philosophy student, set himself on fire on Wenceslas Square, issuing a warning before his death not to follow in his footsteps, a warning displayed on the walls of the Communism museum. The Plastic People played psychedelic garage rock typical of American FM stations of the time – led by front man Milan Hlavsa, a butcher by training, the group sang controversial songs of freedom, first in English, then in Czech. Their first studio album was called “Egon Bondy’s Happy Hearts Club Banned,” an ironic spin on poems by outlawed Czech poet Egon Bondy and the everpresent Liverpudlian Fab Four.

Inspired by the Velvet Underground, a group of Prague natives formed a band called the Plastic People of the Universe, just a month after the Prague Spring was suppressed by Warsaw Pact troops and just after Jan Palach, a philosophy student, set himself on fire on Wenceslas Square, issuing a warning before his death not to follow in his footsteps, a warning displayed on the walls of the Communism museum. The Plastic People played psychedelic garage rock typical of American FM stations of the time – led by front man Milan Hlavsa, a butcher by training, the group sang controversial songs of freedom, first in English, then in Czech. Their first studio album was called “Egon Bondy’s Happy Hearts Club Banned,” an ironic spin on poems by outlawed Czech poet Egon Bondy and the everpresent Liverpudlian Fab Four. In 1970, the Communist government revoked the license for the Plastics to perform in public, forcing them to take the second part of the band title that had so inspired them literally – the Plastics were going underground. For years, they remained relatively off the radar, until 1976, when they played a music festival in the town of Bojanvovice, leading to arrests of all of the band members on charges of “subversive activities against the state.”

In 1970, the Communist government revoked the license for the Plastics to perform in public, forcing them to take the second part of the band title that had so inspired them literally – the Plastics were going underground. For years, they remained relatively off the radar, until 1976, when they played a music festival in the town of Bojanvovice, leading to arrests of all of the band members on charges of “subversive activities against the state.” Marta Kubisova is just one of the many Czechs who was inspired by the “Hey Jude” single. The actress and singer first graced the public eye when “Prayer for Marta” became a symbol of national resistance in 1968, during the Prague Spring. And in the same year, when “Hey Jude” was released, Marta adapted it, releasing her own translated version in 1969 – the cover made her a local star.

Marta Kubisova is just one of the many Czechs who was inspired by the “Hey Jude” single. The actress and singer first graced the public eye when “Prayer for Marta” became a symbol of national resistance in 1968, during the Prague Spring. And in the same year, when “Hey Jude” was released, Marta adapted it, releasing her own translated version in 1969 – the cover made her a local star.

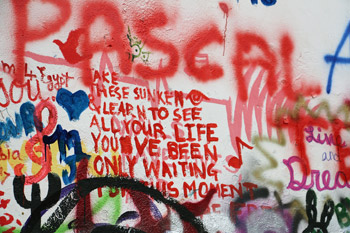

Today, the John Lennon wall still attracts hundreds of tourists, who come to look at the ever-changing paintings. The Knights of Malta have long since ceased trying to stop the graffiti. But while John Lennon is a meaningful symbol for many, it’s hard to understand just how much his music meant to young Czechs in the 80s.

Today, the John Lennon wall still attracts hundreds of tourists, who come to look at the ever-changing paintings. The Knights of Malta have long since ceased trying to stop the graffiti. But while John Lennon is a meaningful symbol for many, it’s hard to understand just how much his music meant to young Czechs in the 80s. The wall first popped up in 1980, just after Lennon’s death, just a few years before Prague students took to the streets. The wall was created in memory of the man who, for them, embodied the freedom and liberation they so craved. “Lennonism,” then, a celebration of freedom and independence, became the counterpoint to Communism, and the evidence remains in Prague today, years after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

The wall first popped up in 1980, just after Lennon’s death, just a few years before Prague students took to the streets. The wall was created in memory of the man who, for them, embodied the freedom and liberation they so craved. “Lennonism,” then, a celebration of freedom and independence, became the counterpoint to Communism, and the evidence remains in Prague today, years after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

When, just over a week ago, I arrived in Valencia, Spain’s third largest city located on the Mediterranean and full of history, I did so, literally, with a bang. It’s the time of year when a spectacular festival, known as Las Falles, is celebrated, culminating on the 19th of March with a parade of gigantic ninots, papier-mâché effigies which are, at the end, burnt in a massive bonfire to chase winter out and welcome spring. Fireworks, crackers, you name it, anything which makes noise and has color will assault the senses.

When, just over a week ago, I arrived in Valencia, Spain’s third largest city located on the Mediterranean and full of history, I did so, literally, with a bang. It’s the time of year when a spectacular festival, known as Las Falles, is celebrated, culminating on the 19th of March with a parade of gigantic ninots, papier-mâché effigies which are, at the end, burnt in a massive bonfire to chase winter out and welcome spring. Fireworks, crackers, you name it, anything which makes noise and has color will assault the senses. The story of the Holy Grail or chalice, which is the cup Jesus supposedly used during the Last Supper, has fired the imagination over centuries. Did it survive, where was it, is the story really true?

The story of the Holy Grail or chalice, which is the cup Jesus supposedly used during the Last Supper, has fired the imagination over centuries. Did it survive, where was it, is the story really true? Given the many legends, it is not surprising that there are more than one chalice which lay claim to being the ‘real thing’. It will appear though that the chalice kept in the cathedral of Valencia has the most valid claim to authenticity. At least, it has been the official papal chalice for centuries, last used as such by Pope Benedict XVI in June 2006. It was given to the cathedral of Valencia by King Alfonso V of Aragon in 1436.

Given the many legends, it is not surprising that there are more than one chalice which lay claim to being the ‘real thing’. It will appear though that the chalice kept in the cathedral of Valencia has the most valid claim to authenticity. At least, it has been the official papal chalice for centuries, last used as such by Pope Benedict XVI in June 2006. It was given to the cathedral of Valencia by King Alfonso V of Aragon in 1436. It’s very easy to get around Valencia’s historic center on foot, leading past several other landmarks like the Central Market and La Lonja de la Seda, the silk exchange. The cathedral was consecrated in 1238 and is basically a Gothic structure. Built over a former Visgothic cathedral which was turned into a mosque during the occupation by the Arabs, the cathedral also shows Romanesque, Renaissance, Baroque and Neo Classical elements. What first catches the eye is Miguelete, the octagonal bell tower which looms up near the main portal and can be climbed, offering a fabulous view over the city, port and river.

It’s very easy to get around Valencia’s historic center on foot, leading past several other landmarks like the Central Market and La Lonja de la Seda, the silk exchange. The cathedral was consecrated in 1238 and is basically a Gothic structure. Built over a former Visgothic cathedral which was turned into a mosque during the occupation by the Arabs, the cathedral also shows Romanesque, Renaissance, Baroque and Neo Classical elements. What first catches the eye is Miguelete, the octagonal bell tower which looms up near the main portal and can be climbed, offering a fabulous view over the city, port and river.