Cesena, Italy

by Susan Zuckerman

In a spectacular fire in Umberto Eco’s novel, The Name of the Rose, the library of a medieval abbey burns to the ground. The library on which this fictional one was based, however, is still completely intact: La Biblioteca Malatestiana, Europe’s first public library and the pride of Cesena, Italy.

Built between 1447 and 1452 in this small city not far from Bologna, it is an early Renaissance gem. Franciscan monks originally proposed building a library within their monastery, and Pope Eugene IV gave permission, but it was Novello Malatesta, the Lord of Cesena, who provided the funds and decided it would be open to the public.

When I first approach, the exterior seems unremarkable, a rather austere, two-storey, peach-coloured building on the edge of a small square that serves mainly as a parking lot. This is the pride of Cesena? I can’t say I’m impressed so far. I enter a long, echoing hallway with a display of photos of brilliantly illuminated pages from Plutarch’s Lives. It feels so modern and barren. I wonder where the actual books are.

When I first approach, the exterior seems unremarkable, a rather austere, two-storey, peach-coloured building on the edge of a small square that serves mainly as a parking lot. This is the pride of Cesena? I can’t say I’m impressed so far. I enter a long, echoing hallway with a display of photos of brilliantly illuminated pages from Plutarch’s Lives. It feels so modern and barren. I wonder where the actual books are.

My private tour guide, a local historian named Alberto, greets me. He has a broad face and short-cropped black hair, and carries two large ornate keys. He leads me upstairs to a set of tall double doors. The dark walnut wood is intricately carved with coats-of-arms and elephants. Above is a triangular tympanum of white marble featuring a sculpted elephant draped in a scroll bearing a Latin inscription that Alberto translates: ‘Elephants aren’t afraid of mosquitoes.’

‘The elephant is the symbol of the Malatesta family,’ Alberto tells me, ‘because elephants are powerful and have good memories. The Malatestas haughtily regarded their enemies as merely annoying ‘mosquitoes’. They also were known for deformities of their heads and their very long noses. In fact, Malatesta means bad head. Portraits of them are always in profile to show their good side.’

‘The elephant is the symbol of the Malatesta family,’ Alberto tells me, ‘because elephants are powerful and have good memories. The Malatestas haughtily regarded their enemies as merely annoying ‘mosquitoes’. They also were known for deformities of their heads and their very long noses. In fact, Malatesta means bad head. Portraits of them are always in profile to show their good side.’

Before he opens the door, Alberto explains the two keys needed to unlock it. A Franciscan monk, the Director of the monastery, always kept one key and the Council of Elders, on behalf of the community of Cesena, kept the other. The monks took care of the books, but the city owned them and guaranteed public access.

When the door opens, I am shocked to see that it looks more like a small church than a library. The nave has a high-vaulted ceiling with a large, clear-paned rosette window at the far end. Brilliant sunlight spills into the room like a holy presence. There is one central aisle and row upon row of what look like pews. In each ‘pew’ the books lie flat on shelves beneath a slanted desktop. Iron chains attach the books to a metal rod running along each shelf. The books can thus be placed on the desk above, but are not usually removed from the library. Only one book lies open at present, and we are not allowed to touch anything.

The more I look around this hushed, ancient space, and the more Alberto tells me, the more awestruck I become. In the 15th century, one large book would have been worth about the same as a country home with all its livestock, and 343 manuscripts are kept here. All are hand-printed by the Franciscan monks on pages made of goat and sheep vellum. The covers are leather-bound wood, with metal studs so the leather doesn’t rub on the shelf. A perfect micro-climate, unheated and with air circulation from the vaulted ceiling, has protected the books. In fact, the Malatesta Library is recognized throughout the world as the only humanist library whose buildings, furnishings, and book collection are fully and perfectly preserved.

The more I look around this hushed, ancient space, and the more Alberto tells me, the more awestruck I become. In the 15th century, one large book would have been worth about the same as a country home with all its livestock, and 343 manuscripts are kept here. All are hand-printed by the Franciscan monks on pages made of goat and sheep vellum. The covers are leather-bound wood, with metal studs so the leather doesn’t rub on the shelf. A perfect micro-climate, unheated and with air circulation from the vaulted ceiling, has protected the books. In fact, the Malatesta Library is recognized throughout the world as the only humanist library whose buildings, furnishings, and book collection are fully and perfectly preserved.

‘One of the most precious manuscripts is a 13th century illuminated Bible,’ Alberto tells me, ‘ and the oldest manuscript is from the 7th century, the Etymologiae of St. Isidore, which is a summary of universal knowledge. There are many classics written in ancient Greek, Latin, and Hebrew, and many medical books.’

He points upward and continues, ‘The green ceiling is the colour of surgeons. It is a soothing, healing colour and signifies the great contribution of medical books, some from Novello’s personal physician, who later became physician to the Pope.’ Alberto also explains that this green ceiling, red brick floor, and white columns and capitals are the colours of the Italian flag.

Because this library was so well lit, it was one of the first where books could be read in the same room in which they were shelved. The circular rosette window faces east and the sunlight pouring though is the main light source. Along the south and north walls are also numerous arched Venetian-style windows. The panes consist of many circular bottle bottoms tinged pink and green, which act as lens to magnify and radiate the light onto each row of desks. I squint my eyes and can imagine robed Franciscan monks toiling to copy manuscripts in fine, painstaking calligraphy, illuminating the margins with brilliant colours. As the sun and shadows shift, the monks pick up their pages and pens and follow the daylight around the room.

Because this library was so well lit, it was one of the first where books could be read in the same room in which they were shelved. The circular rosette window faces east and the sunlight pouring though is the main light source. Along the south and north walls are also numerous arched Venetian-style windows. The panes consist of many circular bottle bottoms tinged pink and green, which act as lens to magnify and radiate the light onto each row of desks. I squint my eyes and can imagine robed Franciscan monks toiling to copy manuscripts in fine, painstaking calligraphy, illuminating the margins with brilliant colours. As the sun and shadows shift, the monks pick up their pages and pens and follow the daylight around the room.

Alberto continues to regale me with fascinating historical connections. The Franciscans were a religious order who took a vow of poverty, tracing their origins to St. Francis of Assisi. Wealthy families often aligned themselves with religious orders. In nearby Florence, Cosimo the Elder, founder of the very powerful Medici dynasty and head of the most powerful bank in Europe at that time, was a benefactor of the Benedictine monks. At a suggestion of the Pope, as penance for all the money he was accumulating, Cosimo Medici built San Marco monastery and library in Florence. As a follower of the Stoic philosophy, he decided to use a humble architectural style with little ornamentation. Novello Malatesta built his library to resemble Cosimo’s, and in fact the two of them traded books for the monks to copy. Centuries later, the books in the Florence library were confiscated by Napoleon as property of the church and subsequently sold. The books in the Malatesta library were saved, however, because they were public property.

Novello’s wife, Violante, also contributed greatly to the library. She was a half-sister of the Duke of Urbino and was highly educated in the humanities in both Urbino and Rome. When she died she provided money for oil to light the library for many years, but no sign of these oil lamps exists, and they perhaps were never used for fear of fire.

Another fascinating historical tidbit stems from graffiti scratched on the wall inside the library: the name ‘Lucretia’. Alberto presumes it was written by the infamous Lucretia Borgia, illegitimate daughter of Pope Alexander VI. She was reputedly a guest at the monastery, stopping there on her way to be married in the nearby city of Ravenna. Alberto grins and his eyes twinkle. ‘Because it was rare for a woman to enter a monastery,’ he says, ‘she would have ‘left her mark’.

Alberto now ushers me across the hall into a room that was formerly the Franciscan monks’ dormitory but later became another repository of precious books: la Biblioteca Piana. This looks a little more like a modern library, lined with glass-doored bookcases that reveal gilded leather spines. The books in this room, about 5000 printed volumes and 100 manuscripts, are the collections of two Popes from Cesena during the 18th and 19th Centuries, Pius VI and Pius VII.

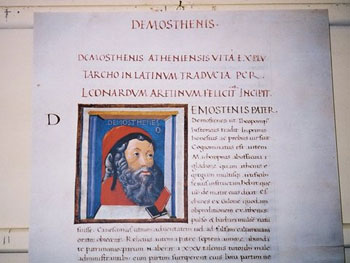

Numerous books are open and on display in glass cases. One, from 1444, is a book of legal trials and sentences from Florence. Another, from 1496, is a book of liturgies, a different one for each Sunday’s mass for a year. I’m especially drawn to seven huge choral books, made large enough for a whole choir to view. The capital letters and borders are amazingly intricate, illuminated with real gold leaf and brilliant green, pink, blue, red, and purple. Many also have postcard-sized illustrations, of strange beasts, birds, flowers. I even notice that pictured inside some of the capital letters are toiling monks.

Numerous books are open and on display in glass cases. One, from 1444, is a book of legal trials and sentences from Florence. Another, from 1496, is a book of liturgies, a different one for each Sunday’s mass for a year. I’m especially drawn to seven huge choral books, made large enough for a whole choir to view. The capital letters and borders are amazingly intricate, illuminated with real gold leaf and brilliant green, pink, blue, red, and purple. Many also have postcard-sized illustrations, of strange beasts, birds, flowers. I even notice that pictured inside some of the capital letters are toiling monks.

Alberto tells me about these choral books, commissioned by Cardinal Bessarione from Constantinople in the 15th Century. Bessarione had attempted to join the Greek Orthodox and Catholic Churches to better withstand sieges from the Muslim Turks, but in 1451 Constantinople fell to the Turks and the churches there were turned into mosques. Not able to take the choral books back home, Bessarione donated them to Violente Malatesta. They are huge books, each page being one sheepskin. Alberto explains that book copying and binding was a huge industry for the town of Cesena.

Who would have thought that this very plain-looking building would hold such beautiful ancient treasures, such a glimpse into the world of knowledge before the printing press? Now I can see why La Biblioteca Malatestiana is the pride of Cesena. You can’t tell a library by its cover.

Private Tour: Brothels and Bordellos of Bologna

If You Go:

Guided Tours

Available daily from Istituzione Biblioteca Malatestian, piazza Bufalini, 1 – 47023 Cesena, Italy

Telephone: 0547 610892

Official website: www.malatestiana.it (also available in Google translation)

Discover Ferrari & Pavarotti Land from Bologna

Bologna Food Tour from a local perspective

Other Places to Visit Nearby:

♦ Rocca Malatestiana: Just off the central square of Cesena, the Piazza del Popolo, in the castle fortress built by the Malatesta family between 1377 and 1480. Tours are available in English. Displays include agricultural implements, jousting equipment, and suits of armour. Narrow passageways and a labyrinth of stairs lead down to a torture chamber. You can also walk all around the top of the wall for magnificent views back into the hills and out to the Adriatic Sea.

♦ Cesenatico: A delightful seaside resort town and historical port, this may be the place to stay, about 30 minutes from Cesena. (I would recommend the Hotel Lido: www.pollinihotels.it/lido/en)

♦ Ravenna: A UNESCO World Heritage site about 40 minutes from Cesena, this city is renowned for its 4th and 5th century Byzantine monuments featuring absolutely stunning mosaics: www.sacred-destinations.com/italy/ravenna

♦ Republic of San Marino: About 50 minutes from Cesena is the most ancient European Republic, a historic, shopping, and culinary paradise. www.sanmarinosite.com/eng/index.php

Other Links:

♦ Umberto Eco’s novel, The Name of the Rose was made into a movie starring Sean Connery in 1986. The trailer can be viewed here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=CsjKsl1bY0Y

♦ For many years, only scholars and researchers were allowed to view the manuscripts in the Malatesta Library, but in 2002, the 550th anniversary of its foundation, the staff began to develop an on-line Open Catalogue. A list of all manuscripts is available as well as imaged reproductions of many of the manuscripts . To see images of pages in the link below go to Manuscripts and scroll down to Search by Images: www.malatestiana.it/manoscritti/indexg.htm

About the author:

Susan Zuckerman lives near Vancouver, B. C. She is a recently retired elementary school teacher and writes historical fiction. She spent three summers in Italy, mostly in Cesena and Cesenatico.

Photo credits:

1 – Library exterior (Luigi Ghirri)

2 – Demosthenis (Susan Zuckerman)

3 – Library door (Susan Zuckerman)

4 – Library desks (Ivano Giovannini)

5 – Library center aisle, with rosette window (Ivano Giovannini)

6 – Illuminated choral page (Susan Zuckerman)

It is an awakening visiting the country of my family’s heritage. There is much to see and learn, understanding about the village and adjusting to the differences in customs, the diversity of rural life and the outlook on life in general. This is an opportunity to observe and live village life on a daily basis.

It is an awakening visiting the country of my family’s heritage. There is much to see and learn, understanding about the village and adjusting to the differences in customs, the diversity of rural life and the outlook on life in general. This is an opportunity to observe and live village life on a daily basis. I faintly hear the sounds of a rooster crowing somewhere in the valley and also ringing faintly in the distance is the sound of church bells from the Church of the Assumption in Zagradec. The sunlight begins to invade the room and my slumber is shattered by the heavy gong of the bells of Saint Primoz. Added to this myriad of sounds a tractor heads out to the fields just beyond the village edge.

I faintly hear the sounds of a rooster crowing somewhere in the valley and also ringing faintly in the distance is the sound of church bells from the Church of the Assumption in Zagradec. The sunlight begins to invade the room and my slumber is shattered by the heavy gong of the bells of Saint Primoz. Added to this myriad of sounds a tractor heads out to the fields just beyond the village edge.

Good fresh bread does not last long in Slovenia due to the lack of preservatives so frequent trips to the market are required. To obtain groceries and bread we drive to Ivancna Gorica, a city complete with a small train station. The rail line connects Ljubljana and Novo Mesto and is used by passengers. Ivancna Gorica has a population of about 14,000 people and grocery stores of Mercator, Tus, and Hofer. Hofer is the Slovenian version of Aldi. The Mercator soon is our favorite. It is somewhat larger than the others and has a better selection of groceries. We obtain certain staples that should last us for the duration and learn quickly the differences between grocery stores in Slovenia and the United States. The cuts of meat are not the same so we must make due and improvise. It has been a long time since we ate brown eggs (jajce). We were able to purchase some in the Mercator and they were good. But the best and tastiest were provided by some of the neighbors in the village. They have thick shells and rich yellow yolks. We enjoy them for breakfast in the morning and they are delicious with ham (sunka). One day we have a taste for hotdogs or wieners and they have a variety with pork, beef, and some with horsemeat. However they are just not the same, but their homemade sausage is tastier.

Good fresh bread does not last long in Slovenia due to the lack of preservatives so frequent trips to the market are required. To obtain groceries and bread we drive to Ivancna Gorica, a city complete with a small train station. The rail line connects Ljubljana and Novo Mesto and is used by passengers. Ivancna Gorica has a population of about 14,000 people and grocery stores of Mercator, Tus, and Hofer. Hofer is the Slovenian version of Aldi. The Mercator soon is our favorite. It is somewhat larger than the others and has a better selection of groceries. We obtain certain staples that should last us for the duration and learn quickly the differences between grocery stores in Slovenia and the United States. The cuts of meat are not the same so we must make due and improvise. It has been a long time since we ate brown eggs (jajce). We were able to purchase some in the Mercator and they were good. But the best and tastiest were provided by some of the neighbors in the village. They have thick shells and rich yellow yolks. We enjoy them for breakfast in the morning and they are delicious with ham (sunka). One day we have a taste for hotdogs or wieners and they have a variety with pork, beef, and some with horsemeat. However they are just not the same, but their homemade sausage is tastier.

Cannes needs little introduction having achieved such film fame both Mickey Mouse and the Pink Panther themselves have left their hand prints in cement along its coastal promenade. Beach restaurants crowd the sands, taking possession of waterfront for their patrons and leaving but small tailings for the public. From the heights of its old castle can be seen the Cheshire Cat-smiling beach grinning out to sea. A sea filled with yachts to make a mariner drool and a beehive of business. Amid the watercraft run ferries to the nearby Lerin Islands, each isle staking its own claim to fame.

Cannes needs little introduction having achieved such film fame both Mickey Mouse and the Pink Panther themselves have left their hand prints in cement along its coastal promenade. Beach restaurants crowd the sands, taking possession of waterfront for their patrons and leaving but small tailings for the public. From the heights of its old castle can be seen the Cheshire Cat-smiling beach grinning out to sea. A sea filled with yachts to make a mariner drool and a beehive of business. Amid the watercraft run ferries to the nearby Lerin Islands, each isle staking its own claim to fame. The largest, Ile Ste. Marguerite, holds the fortress, Fort Royal, and prison where the famed Man in the Iron Mask was held. Trails, museums and restaurants abound for the pleasure of tourists. We chose the smaller but no less interesting Ile St. Honorat where Cistercian monks have returned to a monastic life dating back to the 15th century. The church tower, rising high above waving palm trees, is readily visible from the coastal trail and overlooks the older remains of a fortified monastery jutting daringly into the very seas from which marauders came for plunder. The trail is dotted with chapels and legacies of war, though the contemporary peacefulness of the place makes turmoil seem so alien.

The largest, Ile Ste. Marguerite, holds the fortress, Fort Royal, and prison where the famed Man in the Iron Mask was held. Trails, museums and restaurants abound for the pleasure of tourists. We chose the smaller but no less interesting Ile St. Honorat where Cistercian monks have returned to a monastic life dating back to the 15th century. The church tower, rising high above waving palm trees, is readily visible from the coastal trail and overlooks the older remains of a fortified monastery jutting daringly into the very seas from which marauders came for plunder. The trail is dotted with chapels and legacies of war, though the contemporary peacefulness of the place makes turmoil seem so alien. Mougins is, at first, unassuming until you learn the real medieval town is perched above the main road. It is a relatively short but steep climb to the jewel that draws tourists in their numbers. A less frequent bus travels the route if time and your patience permit. Most famed for its highly rated restaurants and the annual week-long Gourmet Festival it is equally appealing for its twisting narrow streets, plazas, galleries and studios. It appears as if the town has grown out of the hill itself as buildings rise and fall like protruding tree roots. The church bell chimed above us and echoed through the streets. Narrow lanes framed camera-ready shots. Life hums here.

Mougins is, at first, unassuming until you learn the real medieval town is perched above the main road. It is a relatively short but steep climb to the jewel that draws tourists in their numbers. A less frequent bus travels the route if time and your patience permit. Most famed for its highly rated restaurants and the annual week-long Gourmet Festival it is equally appealing for its twisting narrow streets, plazas, galleries and studios. It appears as if the town has grown out of the hill itself as buildings rise and fall like protruding tree roots. The church bell chimed above us and echoed through the streets. Narrow lanes framed camera-ready shots. Life hums here.

Tagging along with my wife and daughter I had little chance of avoiding perfumeries but more significantly the International Museum of Perfume. Even the limited range of my sniffer was awakened in this three level marvel which seemed to fit into the town like a piece from a jig saw. Everything you wanted to known about perfume is there. History, interactive aroma displays, a world of perfume containers from elegant to humorous and movies had us leaving more than two hours within its walls. When we emerged it was in another part of the town near a bronze statue of a parfumeur and a plaza with a spectacular view over the Mediterranean, incorporating Mougins and Cannes.

Tagging along with my wife and daughter I had little chance of avoiding perfumeries but more significantly the International Museum of Perfume. Even the limited range of my sniffer was awakened in this three level marvel which seemed to fit into the town like a piece from a jig saw. Everything you wanted to known about perfume is there. History, interactive aroma displays, a world of perfume containers from elegant to humorous and movies had us leaving more than two hours within its walls. When we emerged it was in another part of the town near a bronze statue of a parfumeur and a plaza with a spectacular view over the Mediterranean, incorporating Mougins and Cannes.

Sintra, Portugal

Sintra, Portugal Once I pay for my ticket at the ticket office housed in a trailer, I follow the signs and go through the turnstile. I walk past some workers manning a zip line that allows them to bring up wood planks and other constructions materials from down below for restoration work at the castle. I follow the signs along the path.

Once I pay for my ticket at the ticket office housed in a trailer, I follow the signs and go through the turnstile. I walk past some workers manning a zip line that allows them to bring up wood planks and other constructions materials from down below for restoration work at the castle. I follow the signs along the path. nce I reach the battlements, I can see undulating land disappearing in the distance beyond the stone walls. The Portuguese flag and the Moorish banner flutter in the cool winter breeze. It felt damp and cold in the shade but warm –too warm to wear a jacket- out in the sun. The turrets and keep glowed in the afternoon light, in sharp contrast with the darkness created by the dense vegetation below.

nce I reach the battlements, I can see undulating land disappearing in the distance beyond the stone walls. The Portuguese flag and the Moorish banner flutter in the cool winter breeze. It felt damp and cold in the shade but warm –too warm to wear a jacket- out in the sun. The turrets and keep glowed in the afternoon light, in sharp contrast with the darkness created by the dense vegetation below. The Moorish invaders began to build what is now known as the Moorish Castle (Castelo dos Mouros) in the 8th century. Its vantage point at the top of the hill is a perfect defensive position. It’s easy to imagine the sentries marching along the walls, keeping an eye out for the Christian armies. And it is equally easy to picture the hosts of King Afonso VI swarming up the hills in 1093 in a successful attempt to take Sintra from the Moors. The fortress changed hands between Moors and Christians a few times more until Lisbon was conquered by Dom Afonso Henriques (the first king of Portugal) in 1147, when the Moors surrendered the castle to him.

The Moorish invaders began to build what is now known as the Moorish Castle (Castelo dos Mouros) in the 8th century. Its vantage point at the top of the hill is a perfect defensive position. It’s easy to imagine the sentries marching along the walls, keeping an eye out for the Christian armies. And it is equally easy to picture the hosts of King Afonso VI swarming up the hills in 1093 in a successful attempt to take Sintra from the Moors. The fortress changed hands between Moors and Christians a few times more until Lisbon was conquered by Dom Afonso Henriques (the first king of Portugal) in 1147, when the Moors surrendered the castle to him.

Life on Ithaka is quiet. There is no nightlife and very few buses run between the villages. Consequently, taxi drivers do a brisk business. Of the population of 2500, most are elderly and retired people. Most young people leave, preferring life in mainland cities for school and work. Those who do remain, mix agriculture with tourism, but the season is only for two months. The Ithakans want more tourism, but they hope to attract mainly a mature public who can appreciate the island’s unique history.

Life on Ithaka is quiet. There is no nightlife and very few buses run between the villages. Consequently, taxi drivers do a brisk business. Of the population of 2500, most are elderly and retired people. Most young people leave, preferring life in mainland cities for school and work. Those who do remain, mix agriculture with tourism, but the season is only for two months. The Ithakans want more tourism, but they hope to attract mainly a mature public who can appreciate the island’s unique history. Teams of archaeologists have been digging around the island, looking for evidence of Homer’s Ithaka and Odysseus’ Bronze Age city. I visit the Cave of the Nymphs where a team of American archaeologists and students are busy sifting and sorting through rubble brought up from a ten meter pit. This cave is believed to be the one where Odysseus hid the gifts given to him by the Phaecians when he returned home after his long, arduous voyage. There were originally two caves in two levels, but they have been collapsed by an earthquake. The cave has two entrances, so it fits the description in The Odyssey. Homer says it was a cave dedicated to the Nymphs. The cave has been used as a religious site, so in this way it fits with the Odyssey. These excavations may help identify the location of Homer’s Ithaka.

Teams of archaeologists have been digging around the island, looking for evidence of Homer’s Ithaka and Odysseus’ Bronze Age city. I visit the Cave of the Nymphs where a team of American archaeologists and students are busy sifting and sorting through rubble brought up from a ten meter pit. This cave is believed to be the one where Odysseus hid the gifts given to him by the Phaecians when he returned home after his long, arduous voyage. There were originally two caves in two levels, but they have been collapsed by an earthquake. The cave has two entrances, so it fits the description in The Odyssey. Homer says it was a cave dedicated to the Nymphs. The cave has been used as a religious site, so in this way it fits with the Odyssey. These excavations may help identify the location of Homer’s Ithaka. Is Ithaka the Homeric Ithaka? German archaeologists have claimed that the island of Lefkada is really the island Homer described. Why would Odysseus have his kingdom a small island such as Ithaka?

Is Ithaka the Homeric Ithaka? German archaeologists have claimed that the island of Lefkada is really the island Homer described. Why would Odysseus have his kingdom a small island such as Ithaka?