Mainz, Germany

by W. Ruth Kozak

New computer technology including the current rage for e-books, has brought about a new printing revolution, and it seems that traditional printing presses will soon be extinct. When I was an aspiring young journalist fresh out of high school working in a newspaper editorial department, one of my tasks was to run errands to the composing room. I was in awe of the type-setters who sat behind their massive machines preparing the print for that day’s newspaper. My most prize possession was an old Underwood manual typewriter. The printed word has always meant a lot to me, so when I visited Mainz, Germany recently, I made a point of visiting the Gutenberg Museum, to have a look at the world’s first printing press. It was in Mainz in the early 1450s that the first European books were printed using moveable type.

A German goldsmith, printer and publisher, Johannes Gutenberg invented the mechanical moveable type printing press and this invention started the Printing Revolution. His first major work was the Gutenberg Bible (known as the 42-line Bible). 180 of them were printed on paper and vellum, though only 21 copies survive, two of them may be seen in the museum. There is also a replica of Gutenberg’s printing press, rebuilt according to woodcuts from the 15th and 16th century.

A German goldsmith, printer and publisher, Johannes Gutenberg invented the mechanical moveable type printing press and this invention started the Printing Revolution. His first major work was the Gutenberg Bible (known as the 42-line Bible). 180 of them were printed on paper and vellum, though only 21 copies survive, two of them may be seen in the museum. There is also a replica of Gutenberg’s printing press, rebuilt according to woodcuts from the 15th and 16th century.

Located in the heart of Mainz historic inner city, right next to an impressive Romanesque cathedral, the Museum was founded in 1900 to honour the inventor and to exhibit the writing and printing techniques of as many different culture as possible. Many of the objects and presses were donated by publishers and manufacturers. Later the museum expanded to include book art, graphics and other types of printing, plus modern artists books.

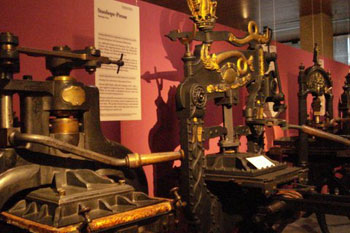

This museum is a must-see for anyone interested in books and printing. The Gutenberg Museum displays two copies of the Bible and Shuelburgh Bible as well as other publications representing the history of the printed word. Here you may see the very earliest typesetting machines and books that were published centuries after the Gutenberg Bible. There is also a small library open to the public that contains a collection of books from the 17th to the 20th centuries.

This museum is a must-see for anyone interested in books and printing. The Gutenberg Museum displays two copies of the Bible and Shuelburgh Bible as well as other publications representing the history of the printed word. Here you may see the very earliest typesetting machines and books that were published centuries after the Gutenberg Bible. There is also a small library open to the public that contains a collection of books from the 17th to the 20th centuries.

After you’ve looked at the fascinating displays, be sure and visit the Museum’s gift shop where you’ll find an interesting array of unique souvenirs to purchase as mementos of your visit.

Wiesbaden and Mainz Day Trip from Frankfurt

If You Go:

The Museum is open from Tuesday through Saturday, 9 to 5 and Sundays 11 to 3. Closed Monday and holidays. Admission: 5 Euro adult, 2 Euro children 8 – 18, 3 Euro students and disabled.

About the author:

Ruth has been interested in the printed word since she started reading as a child, and then when she got her first typewriter at the age of 16. When she worked as a copy-girl in the Vancouver Sun after she graduated from high-school in the ‘50s, she became familiar with printing presses. So this visit to the Gutenburg Museum was a fascinating experience especially since these days it’s the computer age and those old presses are now part of our history.

All photographs are by W. Ruth Kozak.

On March 20th, 1933, Heinrich Himmler and the temporary chief of police in Munich announced that a concentration camp had been built in small town of Dachau in Germany to imprison anyone who “opposed’ the Nazi political party.

On March 20th, 1933, Heinrich Himmler and the temporary chief of police in Munich announced that a concentration camp had been built in small town of Dachau in Germany to imprison anyone who “opposed’ the Nazi political party. The prisoners attended roll call twice a day. During this time they were forced to line up in front of the barracks and stand motionless for an hour as the camp officers would count each prisoner. If anyone had died during the night, the corpse would then be dragged to the roll call area in front of all the other prisoners to be counted. If one of the prisoners had attempted to escape during the night, all of the other inmates were forced to stand at attention for hours on end, regardless of whether the attempt was successful or not. The officers would often torture or punish the prisoner for the others to witness. Sometimes the sick and dying inmates would collapse during roll call, and if any of the fellow inmates dared to help them, they would be punished. Punishment became an hourly occurrence inside Dachau. Prisoners were punished by food withdrawal, mail bans, or at worst, the infamous pole-hanging. Inmates were forced to work throughout the entire day and well into the evening, and were only given a limited amount of time to sleep during the night. They were also forced to put on heavy winter coats while they worked outside during the summer months, or even stand naked while they worked in the cold. If a prisoner was declared “unfit for work,” they would then be transported to the Hartheim Castle, (which was about 17 kilometers away from Linz in Germany); never to be seen or heard from again.

The prisoners attended roll call twice a day. During this time they were forced to line up in front of the barracks and stand motionless for an hour as the camp officers would count each prisoner. If anyone had died during the night, the corpse would then be dragged to the roll call area in front of all the other prisoners to be counted. If one of the prisoners had attempted to escape during the night, all of the other inmates were forced to stand at attention for hours on end, regardless of whether the attempt was successful or not. The officers would often torture or punish the prisoner for the others to witness. Sometimes the sick and dying inmates would collapse during roll call, and if any of the fellow inmates dared to help them, they would be punished. Punishment became an hourly occurrence inside Dachau. Prisoners were punished by food withdrawal, mail bans, or at worst, the infamous pole-hanging. Inmates were forced to work throughout the entire day and well into the evening, and were only given a limited amount of time to sleep during the night. They were also forced to put on heavy winter coats while they worked outside during the summer months, or even stand naked while they worked in the cold. If a prisoner was declared “unfit for work,” they would then be transported to the Hartheim Castle, (which was about 17 kilometers away from Linz in Germany); never to be seen or heard from again. The barracks were used as day rooms and dormitories for the prisoners, and although each barrack was designed to hold 200 prisoners, by the end of World War II in 1945, up to 2,000 prisoners were packed into these small living quarters. (The Jewish prisoners slept in barrack #15 which was separated from the rest of the camp with barbed wire).

The barracks were used as day rooms and dormitories for the prisoners, and although each barrack was designed to hold 200 prisoners, by the end of World War II in 1945, up to 2,000 prisoners were packed into these small living quarters. (The Jewish prisoners slept in barrack #15 which was separated from the rest of the camp with barbed wire). Dachau’s crematorium was built in 1940 in order to deal with the increasing number of deaths at the camp, followed by a larger crematorium as well as a gas chamber at the end of 1942. It was inside this gas chamber where the mass murders at Dachau occurred. Fake shower sprouts were installed in the ceiling in order to fool the prisoners into thinking they were going to take a shower. Within a period of 15 to 20 minutes, approximately 150 victims would have been poisoned to death inside the gas chamber. A separate room in the crematorium area known as the “death chamber” used to store the corpses that were brought in from the camp. These corpses were then cremated in one of the stoves, and it is said that each of the stoves could cremate two to three bodies at the same time.

Dachau’s crematorium was built in 1940 in order to deal with the increasing number of deaths at the camp, followed by a larger crematorium as well as a gas chamber at the end of 1942. It was inside this gas chamber where the mass murders at Dachau occurred. Fake shower sprouts were installed in the ceiling in order to fool the prisoners into thinking they were going to take a shower. Within a period of 15 to 20 minutes, approximately 150 victims would have been poisoned to death inside the gas chamber. A separate room in the crematorium area known as the “death chamber” used to store the corpses that were brought in from the camp. These corpses were then cremated in one of the stoves, and it is said that each of the stoves could cremate two to three bodies at the same time. Unfortunately by the time American soldiers discovered Dachau on April 29th, 1945, it was already too late for many of the victims.

Unfortunately by the time American soldiers discovered Dachau on April 29th, 1945, it was already too late for many of the victims.

Percy and Mary Shelley arrived in the tiny seaside village of San Terenzo in 1819 and rented a villa known as “Casa Magni”, whose whitewashed walls and arched colonnade can be found on the promenade. “A lonely house close by the soft and sublime scenes of the Bay of Lerici”, is how Shelley described the villa in his letters. These lines are inscribed on the walls of the now uninhabited villa, along with “I still inhabit this Divine Bay, reading dramas and sailing and listening to the most enchanting music.”

Percy and Mary Shelley arrived in the tiny seaside village of San Terenzo in 1819 and rented a villa known as “Casa Magni”, whose whitewashed walls and arched colonnade can be found on the promenade. “A lonely house close by the soft and sublime scenes of the Bay of Lerici”, is how Shelley described the villa in his letters. These lines are inscribed on the walls of the now uninhabited villa, along with “I still inhabit this Divine Bay, reading dramas and sailing and listening to the most enchanting music.” A sprinkling of brightly coloured houses line medieval streets that wind up to Lerici’s castle, which overlooks the entrance to the Gulf of Poets. The castle is thought to be the inspiration for Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” Nowadays the castle contains a museum of palaeontology.

A sprinkling of brightly coloured houses line medieval streets that wind up to Lerici’s castle, which overlooks the entrance to the Gulf of Poets. The castle is thought to be the inspiration for Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” Nowadays the castle contains a museum of palaeontology. Shelley’s’ ashes were stored in the wine cellar of The British Consul in Rome before being buried in The Protestant Cemetery in Rome, where John Keats was laid to rest just a year before. After Mary Shelley’s death, her husband’s heart was found wrapped in a page of “Adonais”, Shelley’s famous elegy to Keats. Shelley’s heart was eventually buried in St Peter’s Churchyard in Bournemouth, Dorset.

Shelley’s’ ashes were stored in the wine cellar of The British Consul in Rome before being buried in The Protestant Cemetery in Rome, where John Keats was laid to rest just a year before. After Mary Shelley’s death, her husband’s heart was found wrapped in a page of “Adonais”, Shelley’s famous elegy to Keats. Shelley’s heart was eventually buried in St Peter’s Churchyard in Bournemouth, Dorset.

The Vidroule River flows leisurely along its defined banks flanked by nurtured trees and a tended walkway. A pastoral setting so peaceful we were entertained by a solitary otter swimming slowly by, oblivious to the nearness of people and cars. Cafes colonize the walkway with tented outdoor seating offering customers a tree shaded view of the Vidroule and its famous bridge. In its time the bridge was the only crossing of the Vidroule between the Mediterranean and the Cevenne Mountains; hence Sommieres’ ancient importance.

The Vidroule River flows leisurely along its defined banks flanked by nurtured trees and a tended walkway. A pastoral setting so peaceful we were entertained by a solitary otter swimming slowly by, oblivious to the nearness of people and cars. Cafes colonize the walkway with tented outdoor seating offering customers a tree shaded view of the Vidroule and its famous bridge. In its time the bridge was the only crossing of the Vidroule between the Mediterranean and the Cevenne Mountains; hence Sommieres’ ancient importance.

Today the chateau, partially restored and turned to museum remembrances, recalls eras of siege and troubles. Initially constructed between the 10th and 11th centuries at its height it had two towers frowning over river and town of which but one remains. Its first mention in records was in 1041. As its prominence passed it was employed as a prison and eventually lapsed into partial private and public ownership. From its heights town and country spread out in a broad vista.

Today the chateau, partially restored and turned to museum remembrances, recalls eras of siege and troubles. Initially constructed between the 10th and 11th centuries at its height it had two towers frowning over river and town of which but one remains. Its first mention in records was in 1041. As its prominence passed it was employed as a prison and eventually lapsed into partial private and public ownership. From its heights town and country spread out in a broad vista. Sommieres, at 4,500 population, is not the prominent town it was those many years ago which makes it all the more inviting as it’s medieval heart continues to dominate and afford much for the wandering feet of visitors. Narrow streets and lanes sprout off in all directions yet maintain the Roman dominance of grid patterns. In some cases arches over streets have evolved into windowed buildings creating little tunnels to explore and, dotted throughout, are small arches spanning between buildings as some form of support. The narrowed confines open to readily framed vistas for telling photos.

Sommieres, at 4,500 population, is not the prominent town it was those many years ago which makes it all the more inviting as it’s medieval heart continues to dominate and afford much for the wandering feet of visitors. Narrow streets and lanes sprout off in all directions yet maintain the Roman dominance of grid patterns. In some cases arches over streets have evolved into windowed buildings creating little tunnels to explore and, dotted throughout, are small arches spanning between buildings as some form of support. The narrowed confines open to readily framed vistas for telling photos.

The bridge has also felt the steps of moved masses coming from Mozart’s premier of “Don Giovanni.” Perhaps the happy tempo of these steps felt similar to those that walked the bridge in 1918 when Czech people crossed it — citizens of a sovereign country for the first time in their long history.

The bridge has also felt the steps of moved masses coming from Mozart’s premier of “Don Giovanni.” Perhaps the happy tempo of these steps felt similar to those that walked the bridge in 1918 when Czech people crossed it — citizens of a sovereign country for the first time in their long history.

Then came The Devil. No one knows exactly when he first came, but everyone agrees it was over 10 years ago. On the edge of the bridge he set up shop where he thought he belonged, next to the other artists selling their creations to eager tourists in front of the Mala Strana tower.

Then came The Devil. No one knows exactly when he first came, but everyone agrees it was over 10 years ago. On the edge of the bridge he set up shop where he thought he belonged, next to the other artists selling their creations to eager tourists in front of the Mala Strana tower. Did he believe he was the devil? Why the Charles Bridge? Was it all a ploy for the money or was their some higher reason for what he did? I don’t know. And I won’t know. When I set out to find him and ask, he was not to be found. The other vendors informed me with long faces that he recently passed away.

Did he believe he was the devil? Why the Charles Bridge? Was it all a ploy for the money or was their some higher reason for what he did? I don’t know. And I won’t know. When I set out to find him and ask, he was not to be found. The other vendors informed me with long faces that he recently passed away.