Ithaka, Greece

by W. Ruth Kozak

We approached the coast of this island and brought our ship into the shelter of the haven without making a sound. Some god must have guided us in…”

– Homer, The Odyssey

The ferry rounds Ithaka’s rocky headland into a secret cove. Pretty houses cluster on the slopes of the low hills that surround a horseshoe-shaped bay. The town of Vathi is hidden. You don’t know it is there until you round the arm of the harbor.

Ithaka is an island that ‘happens’ to you. Its curious atmosphere eludes those who would try to pin it down with facts, archaeological and otherwise. Along the island’s rugged coastline are pebbled beaches of moonlike opalescence with water clear as platinum. The ocean, mirror-still one moment can turn to a raging tempest. Ithaka’s hillsides are scented with wild sage and oregano, dotted with vibrant wild-flowers and silvery olive groves. And surrounding the tranquil orchards and vineyards are the high menacing mountains. Homer described it as “an island of goat pastures rising rocklike from the sea.” Although there are no remains to confirm that the plateau of Marathia was the site of Eumaeus’ pig sties, or that the port town of Vathi corresponds to ancient Phorcys where the Phaecians navigated Odysseus, to most of the island’s inhabitants, Homer’s legend is enough to sustain the imagination.

Life on Ithaka is quiet. There is no nightlife and very few buses run between the villages. Consequently, taxi drivers do a brisk business. Of the population of 2500, most are elderly and retired people. Most young people leave, preferring life in mainland cities for school and work. Those who do remain, mix agriculture with tourism, but the season is only for two months. The Ithakans want more tourism, but they hope to attract mainly a mature public who can appreciate the island’s unique history.

Life on Ithaka is quiet. There is no nightlife and very few buses run between the villages. Consequently, taxi drivers do a brisk business. Of the population of 2500, most are elderly and retired people. Most young people leave, preferring life in mainland cities for school and work. Those who do remain, mix agriculture with tourism, but the season is only for two months. The Ithakans want more tourism, but they hope to attract mainly a mature public who can appreciate the island’s unique history.

Ithakans are known as great navigators and explorers. “The Odyssey” written by the blind poet Homer in the late 7th century BC, depicts the political, cultural and social life of the island during that time. According to tradition, Homer had lived there when he was very young, so he was later able to describe it with such great detail.

Teams of archaeologists have been digging around the island, looking for evidence of Homer’s Ithaka and Odysseus’ Bronze Age city. I visit the Cave of the Nymphs where a team of American archaeologists and students are busy sifting and sorting through rubble brought up from a ten meter pit. This cave is believed to be the one where Odysseus hid the gifts given to him by the Phaecians when he returned home after his long, arduous voyage. There were originally two caves in two levels, but they have been collapsed by an earthquake. The cave has two entrances, so it fits the description in The Odyssey. Homer says it was a cave dedicated to the Nymphs. The cave has been used as a religious site, so in this way it fits with the Odyssey. These excavations may help identify the location of Homer’s Ithaka.

Teams of archaeologists have been digging around the island, looking for evidence of Homer’s Ithaka and Odysseus’ Bronze Age city. I visit the Cave of the Nymphs where a team of American archaeologists and students are busy sifting and sorting through rubble brought up from a ten meter pit. This cave is believed to be the one where Odysseus hid the gifts given to him by the Phaecians when he returned home after his long, arduous voyage. There were originally two caves in two levels, but they have been collapsed by an earthquake. The cave has two entrances, so it fits the description in The Odyssey. Homer says it was a cave dedicated to the Nymphs. The cave has been used as a religious site, so in this way it fits with the Odyssey. These excavations may help identify the location of Homer’s Ithaka.

The site, four kilometers from Vathi, is closed to the public, but I am allowed entry into the dank, cavernous mouth, to look down into the deep pit where the treasures were hidden. I’m not allowed to take photos, and specific questions such as “Have you found anything yet?” go unanswered.

Is Ithaka the Homeric Ithaka? German archaeologists have claimed that the island of Lefkada is really the island Homer described. Why would Odysseus have his kingdom a small island such as Ithaka?

Is Ithaka the Homeric Ithaka? German archaeologists have claimed that the island of Lefkada is really the island Homer described. Why would Odysseus have his kingdom a small island such as Ithaka?

On my way to the town of Stavros, I am driven past the rock-strewn remains of what is believed to be the Bronze Age city. According to Homer’s description, Odysseus’ palace was located at a spot overlooking three seas, and surrounded by three mountains. This location, on the Pilikata Hill, fits the description.

At the town of Stavros, a market town, I am introduced to the curator of the museum, who gives me a personal lecture about all the artifacts. She shows me various objects with roosters, symbolic of Odysseus, and bits of boar’s tusks fashioned into helmets. From the cave of Loizos which collapsed in the 1953 earthquake, there are bronze tripods of the type Odysseus was supposed to have hidden and a fragment of a mask marked “Blessings to Odysseus.” There is also a statuette depicting Odysseus tied to a ship’s mast so that he can resist the siren’s seductive song.

Back in Vathi, I walk along the port to my pension. Cafes animate the harbour. The summer evening is scented with the blue smoke of grilling kebabs and fresh-caught fish. In the harbour are yachts from all over the Mediterranean. I am reluctant to leave this extraordinary island.

The next day, I travel by taxi to the northern port of Frikes and board a ferry bound for Lefkada. As the ferry sets sail across the straits, a pod of dolphins frolic alongside. The white limestone cliffs of Ithaka’s shoreline are striped by eerie silvery pink and blue lights. A light breeze stirs the water. I think of Odysseus’ wife, Penelope, and how she waited all those years for him to return I will not soon forget this journey. Ithaka is a place that will draw me back again, too.

If You Go:

♦ Ferries run daily from the port of Patras, or neighboring islands Kefalonia and Lefkada.

♦ Buses run daily from Athens Kiffisiou Street depot, connecting with the ferry at Patras.

♦ Accommodations are available in private homes and hotels on Ithaka. No camping is allowed.

About the author:

Ruth is a historical-fiction writer who combines her research trips with travel writing. On this visit to Ithaka she was lucky to be escorted to the Odysseus site by the mayor of Ithaka, and introduced to the archaeologist, Sarantis Symeonoglou who was in charge of the digs at the Cave of the Nymphs for the Odysseus Project which began in 1988 under the auspices of Washington University. See more of her writing at: www.ruthkozak.com

All photographs are by W. Ruth Kozak.

All three temples face eastward, presumably to allow the rising sun to shine on any deity statues inside. Furthermore, they are close together on flat terrain which allows for easy comparison. Having these three large structures so close to the road as you arrive is intimidating. You almost feel like their respective deities are still inside demanding your worship and sacrifices.

All three temples face eastward, presumably to allow the rising sun to shine on any deity statues inside. Furthermore, they are close together on flat terrain which allows for easy comparison. Having these three large structures so close to the road as you arrive is intimidating. You almost feel like their respective deities are still inside demanding your worship and sacrifices. The neighboring Temple of Poseidon, dating to 450 BCE, is the largest and best preserved structure on site. Thirty-six honey brown travertine columns form the peristyle. This temple reflects the transition between the Archaic and later Doric styles. Again the remains of two altars are located in front of the structure. Only the larger altar is of Greek origin; the smaller is Roman.

The neighboring Temple of Poseidon, dating to 450 BCE, is the largest and best preserved structure on site. Thirty-six honey brown travertine columns form the peristyle. This temple reflects the transition between the Archaic and later Doric styles. Again the remains of two altars are located in front of the structure. Only the larger altar is of Greek origin; the smaller is Roman. The Ekklesiasterion is located just inside the park fence, opposite the museum. The circular, limestone oratory was the site of democratic assembly for this city-state. This low-lying structure has 10 levels of seats.

The Ekklesiasterion is located just inside the park fence, opposite the museum. The circular, limestone oratory was the site of democratic assembly for this city-state. This low-lying structure has 10 levels of seats. The Valley of the Temples at Agrigento is all that remains of the ancient Greek city of “Akragas”. Founded in 582 BCE, residents would construct eight temples over the next century. Of these, only five are accessible on site.

The Valley of the Temples at Agrigento is all that remains of the ancient Greek city of “Akragas”. Founded in 582 BCE, residents would construct eight temples over the next century. Of these, only five are accessible on site. The Temple of Hera stands at the highest point of the ridge. Twenty five of its 34 honey brown calcarenite columns remain standing, making it the second best preserved temple in the park. This temple was constructed between 450 and 440 BCE.

The Temple of Hera stands at the highest point of the ridge. Twenty five of its 34 honey brown calcarenite columns remain standing, making it the second best preserved temple in the park. This temple was constructed between 450 and 440 BCE. Exit this side of the park to visit the last two temples. The first is the Temple of Castor and Pollux (Dioscuri). Four of the 34 honey brown columns remain standing amidst fruit-laden olive trees. Here visitors find that Greek-style columns were not one solid cylinder. Rather they were assembled from several cylindrical drums. The end of one of these drums features a square indentation. A wooden peg may have been set in this indentation as a means of aligning and stabilizing the drums as they were stacked one upon the other. Visitors should note that some of the drums on site may have belonged to other structures at one time.

Exit this side of the park to visit the last two temples. The first is the Temple of Castor and Pollux (Dioscuri). Four of the 34 honey brown columns remain standing amidst fruit-laden olive trees. Here visitors find that Greek-style columns were not one solid cylinder. Rather they were assembled from several cylindrical drums. The end of one of these drums features a square indentation. A wooden peg may have been set in this indentation as a means of aligning and stabilizing the drums as they were stacked one upon the other. Visitors should note that some of the drums on site may have belonged to other structures at one time. You can put the Valley of the Temples into perspective with a tour of the Archeology Museum.

You can put the Valley of the Temples into perspective with a tour of the Archeology Museum. Arriving at the Neapolis Archeological Park you find little evidence of any ancient structures within. Your first impression is that of a quarry. Appearances are deceiving as the park actually includes the largest Greek theatre in Sicily. This theatre is hidden from view by trees. You only discover the structure when you arrive on site. Carved out of a limestone hill in the 6th century BCE, this theatre held 15,000 spectators in 67 rows of seats. A tunnel around the periphery may have allowed people to enter and exit the theatre quickly. The upper level of the structure features a number of arches carved out of the solid rock as small “grottos”. One of these holds a small waterfall inside. Compare this Greek theatre to the nearby 3rd century CE Roman amphitheatre. The Greek theatre is semicircular and open while the Roman structure is oval and enclosed.

Arriving at the Neapolis Archeological Park you find little evidence of any ancient structures within. Your first impression is that of a quarry. Appearances are deceiving as the park actually includes the largest Greek theatre in Sicily. This theatre is hidden from view by trees. You only discover the structure when you arrive on site. Carved out of a limestone hill in the 6th century BCE, this theatre held 15,000 spectators in 67 rows of seats. A tunnel around the periphery may have allowed people to enter and exit the theatre quickly. The upper level of the structure features a number of arches carved out of the solid rock as small “grottos”. One of these holds a small waterfall inside. Compare this Greek theatre to the nearby 3rd century CE Roman amphitheatre. The Greek theatre is semicircular and open while the Roman structure is oval and enclosed. Leave the Museum and walk to Ortygia Island, the historic center of Syracuse, for more Greek history. Your first destination is the remains of the 6th century BCE Doric Temple of Apollo. Only two of its 42 grey limestone columns and a section of wall remain standing. This temple is in a serious state of disrepair after last having been used as a church during the Norman period almost one thousand years ago. The temple grounds are fenced off from the public.

Leave the Museum and walk to Ortygia Island, the historic center of Syracuse, for more Greek history. Your first destination is the remains of the 6th century BCE Doric Temple of Apollo. Only two of its 42 grey limestone columns and a section of wall remain standing. This temple is in a serious state of disrepair after last having been used as a church during the Norman period almost one thousand years ago. The temple grounds are fenced off from the public.

Looking south standing under a mountain-top cross surrounded by lush vegetation in Sintra’s Romantic-period Pena Palace park I wondered if the human construction in the distance was Lisbon. Then I saw a red bridge glinting in the sun, confirming it was Portugal’s capital city twenty-five miles away on the Tagus estuary. It could have been the Golden Gate bridge signalling San Francisco, but I was a long way from California; and the previous day I’d passed the 25 April bridge and a Rio-style Christ statue on the way to Belem, where Portuguese sailors departed on their most famous voyages of discovery.

Looking south standing under a mountain-top cross surrounded by lush vegetation in Sintra’s Romantic-period Pena Palace park I wondered if the human construction in the distance was Lisbon. Then I saw a red bridge glinting in the sun, confirming it was Portugal’s capital city twenty-five miles away on the Tagus estuary. It could have been the Golden Gate bridge signalling San Francisco, but I was a long way from California; and the previous day I’d passed the 25 April bridge and a Rio-style Christ statue on the way to Belem, where Portuguese sailors departed on their most famous voyages of discovery. A half-fish, half-man statue; an allegory for the creation of the world; greets visitors to the central courtyard of the Pena Palace. Entering the Manueline Cloister to view the living quarters, the sun was almost directly above a tall green plant rising out of a grey turtle-stoned pot in the centre of the unroofed inner courtyard. Upstairs, we could walk past the open bedrooms, which were surprisingly small; and through the communal rooms, which were as stylish as expected. Other highlights of the palace included the small ancient chapel, the Great Royal Hall and the kitchen; the latter now houses a cafe, with an outside terrace.

A half-fish, half-man statue; an allegory for the creation of the world; greets visitors to the central courtyard of the Pena Palace. Entering the Manueline Cloister to view the living quarters, the sun was almost directly above a tall green plant rising out of a grey turtle-stoned pot in the centre of the unroofed inner courtyard. Upstairs, we could walk past the open bedrooms, which were surprisingly small; and through the communal rooms, which were as stylish as expected. Other highlights of the palace included the small ancient chapel, the Great Royal Hall and the kitchen; the latter now houses a cafe, with an outside terrace. On the way up to the palace I had visited the Moorish Castle. It is now mostly just a long wall with towers above foundations being archaeologically excavated, but it still inspires the imagination, and provides the best views on the mountain of Sintra and the northern plain. The castle was built in the eighth and ninth centuries during the Moors’ occupation of the region, before Portuguese forces regained control in the eleventh century. You can buy tickets for both the castle and Pena Palace at the castle entrance. The castle provides a good break if walking from Sintra to the palace. There are also regular buses.

On the way up to the palace I had visited the Moorish Castle. It is now mostly just a long wall with towers above foundations being archaeologically excavated, but it still inspires the imagination, and provides the best views on the mountain of Sintra and the northern plain. The castle was built in the eighth and ninth centuries during the Moors’ occupation of the region, before Portuguese forces regained control in the eleventh century. You can buy tickets for both the castle and Pena Palace at the castle entrance. The castle provides a good break if walking from Sintra to the palace. There are also regular buses. Lisbon’s train station for Sintra is the Rossio, which is conveniently also the city’s most central. Sintra was the only time I used the train service in Lisbon, as I travelled between Lisbon and the south coast by bus; the Eva service was comfortable and punctual, but there were no toilets or rest-stops on the three-hour journey.

Lisbon’s train station for Sintra is the Rossio, which is conveniently also the city’s most central. Sintra was the only time I used the train service in Lisbon, as I travelled between Lisbon and the south coast by bus; the Eva service was comfortable and punctual, but there were no toilets or rest-stops on the three-hour journey.

The Chiado is a popular area of Lisbon, between the city centre; Baixa; and the Bairro Alto district. The latter’s narrow cobbled streets and balconied houses ooze age and character. Everything is in easy walking distance, with the Baixa’s plazas interconnected by picturesque streets, squares and statues. The area was rebuilt after a big earthquake in 1755. Restaurants with smartly dressed waiters and waitresses frame the plazas, continue up the eastern hill towards St. George’s Castle, and down to the Tagus a few blocks to the south.

The Chiado is a popular area of Lisbon, between the city centre; Baixa; and the Bairro Alto district. The latter’s narrow cobbled streets and balconied houses ooze age and character. Everything is in easy walking distance, with the Baixa’s plazas interconnected by picturesque streets, squares and statues. The area was rebuilt after a big earthquake in 1755. Restaurants with smartly dressed waiters and waitresses frame the plazas, continue up the eastern hill towards St. George’s Castle, and down to the Tagus a few blocks to the south. Maybe the sailors sometimes imagine they are Henry the Navigator or Vasco da Gama as they sail out to sea. Henry was a 15th century royal who is credited with being instrumental in developing Portugal’s most rewarding era of exploration and trade. His statue looks out over the Tagus at the head of the impressive Monument to the Discoveries. Behind him are thirty-two notable figures from that era, with sixteen on each side of the caravel-shaped structure; the caravel boat revolutionised Portuguese sailing after being designed with sponsorship from Henry.

Maybe the sailors sometimes imagine they are Henry the Navigator or Vasco da Gama as they sail out to sea. Henry was a 15th century royal who is credited with being instrumental in developing Portugal’s most rewarding era of exploration and trade. His statue looks out over the Tagus at the head of the impressive Monument to the Discoveries. Behind him are thirty-two notable figures from that era, with sixteen on each side of the caravel-shaped structure; the caravel boat revolutionised Portuguese sailing after being designed with sponsorship from Henry. by W. Ruth Kozak

by W. Ruth Kozak

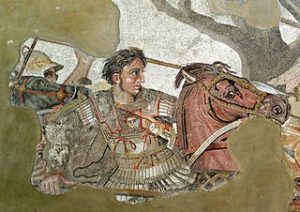

I place my hands on the magnetic lodestone of Samothraki, which represents the Great Mother. The russet-coloured stone burns beneath my touch. Supplicants used to hang iron votives here. Every member of the Macedonian royalty was initiated into the cult of the Great Mother. At one time, Alexander must have stood in this very place. Nearby I find the ruins of a small building erected in 318 BC, dedicated to Alexander and his father Philip by their sons, the join-kings, Philip Arridaios and Alexander IV.

I place my hands on the magnetic lodestone of Samothraki, which represents the Great Mother. The russet-coloured stone burns beneath my touch. Supplicants used to hang iron votives here. Every member of the Macedonian royalty was initiated into the cult of the Great Mother. At one time, Alexander must have stood in this very place. Nearby I find the ruins of a small building erected in 318 BC, dedicated to Alexander and his father Philip by their sons, the join-kings, Philip Arridaios and Alexander IV. Greek poets, tragedians, historians, philosophers, doctors, actors, painters and craftsmen were invited to the Macedonian court. One of these philosophers was Aristotle whom Philip invited to tutor his son at school he had build known as the Nymphaeion” at Mieza, near modern Naoussa. The school, called “The Peripatos” (“walk”) was a two storey L-shaped building linked by staircases, built along the face of the rock. The school’s facilities were set up to harmonize and blend in with the environment, incorporating several caves. Here, in this tranquil setting of lush vegetation, fresh water springs and caves, Aristotle taught Alexander his companions.

Greek poets, tragedians, historians, philosophers, doctors, actors, painters and craftsmen were invited to the Macedonian court. One of these philosophers was Aristotle whom Philip invited to tutor his son at school he had build known as the Nymphaeion” at Mieza, near modern Naoussa. The school, called “The Peripatos” (“walk”) was a two storey L-shaped building linked by staircases, built along the face of the rock. The school’s facilities were set up to harmonize and blend in with the environment, incorporating several caves. Here, in this tranquil setting of lush vegetation, fresh water springs and caves, Aristotle taught Alexander his companions. As I stand looking out over the ruined tiers, I try to image the scene on that fateful day. The wedding was to be a big show with carts bearing statues of the twelve gods, including one with an effigy of Philip crowned as a god. As Philip entered the theatre and dismounted from his horse, he was stabbed to death by his bodyguard. The assassin dashed out of the theatre but was overtaken and killed. Family and political intrigues were behind the murder. At the time, Alexander was estranged from his father. His mother, Olympias, a ruthless, impassioned woman, was jealous of her rivals. Soon afterwards she had Phlip’s newest wife and infant daughter murdered.

As I stand looking out over the ruined tiers, I try to image the scene on that fateful day. The wedding was to be a big show with carts bearing statues of the twelve gods, including one with an effigy of Philip crowned as a god. As Philip entered the theatre and dismounted from his horse, he was stabbed to death by his bodyguard. The assassin dashed out of the theatre but was overtaken and killed. Family and political intrigues were behind the murder. At the time, Alexander was estranged from his father. His mother, Olympias, a ruthless, impassioned woman, was jealous of her rivals. Soon afterwards she had Phlip’s newest wife and infant daughter murdered.

The city was founded by the Phoenicians, but named by the Ancient Greeks as “Panormus”, which then became “Palermo”, with the basic meaning of a place “always fit for landing in.” This aspect becomes pretty clear once to see all the people coming from Tunis and Northern Africa, for whom Palermo represents a way to make some of their dreams come true and the Tyrrhenian Sea is their only escape to a better world.

The city was founded by the Phoenicians, but named by the Ancient Greeks as “Panormus”, which then became “Palermo”, with the basic meaning of a place “always fit for landing in.” This aspect becomes pretty clear once to see all the people coming from Tunis and Northern Africa, for whom Palermo represents a way to make some of their dreams come true and the Tyrrhenian Sea is their only escape to a better world.

In Palermo, you can enjoy a refined trip, full of culture while walking on the magnificent streets in the city centre and visiting the most important treasures left by the ancestors. At the same time you can have an exotic trip, full of shocking discoveries. It all depends on which side or quarter of Palermo you choose to visit.

In Palermo, you can enjoy a refined trip, full of culture while walking on the magnificent streets in the city centre and visiting the most important treasures left by the ancestors. At the same time you can have an exotic trip, full of shocking discoveries. It all depends on which side or quarter of Palermo you choose to visit. Another place of great interest for all tourists is the Capuchin Catacombs, with many mummified corpses in varying degrees of preservation. The main attraction is a little girl, who looks as if she was really still alive.

Another place of great interest for all tourists is the Capuchin Catacombs, with many mummified corpses in varying degrees of preservation. The main attraction is a little girl, who looks as if she was really still alive. You might have heard of Palermo as being a dangerous place to go to, with stories of all the Mafia present around the streets. I’ve walked all alone or with just one other companion in Ballaro, one of the most dangerous quarters in Palermo and never encountered anything scary or frightening.

You might have heard of Palermo as being a dangerous place to go to, with stories of all the Mafia present around the streets. I’ve walked all alone or with just one other companion in Ballaro, one of the most dangerous quarters in Palermo and never encountered anything scary or frightening.