Istanbul, Turkey

by Inke Piegsa-quischotte

Ever since I read Agatha Christie’s intriguing crime novel ‘Murder on the Orient Express’, I wanted to travel on that train. To indulge in the gilded luxury of the train itself, let the mysterious landscapes of the Balkans glide past my window and alight at the final destination: Istanbul, the city which straddles two continents. At the beginning of the 20th century, an infatuation with Istanbul and Turkey had taken hold of European society; actors, artists, writers, journalists and plain rich people, flocked to the Bosporus and their favorite means of transport was the Orient Express.

Composed of sleepers, a dining car and a baggage car, the train featured Lalique chandeliers, a piano and the finest crockery and cutlery. The maiden journey started on October 10th 1882 in Paris and reached Istanbul the next day. The menu consisted of no less than seven courses, oysters and turbot in green sauce included, not to mention fine wines and champagne. In 1977 the train ceased to have Istanbul as its final destination and in 2009 the Orient Express disappeared entirely from the time tables. Several other routes continue though and twice a year the historical trip is repeated, at a very stiff price!

Composed of sleepers, a dining car and a baggage car, the train featured Lalique chandeliers, a piano and the finest crockery and cutlery. The maiden journey started on October 10th 1882 in Paris and reached Istanbul the next day. The menu consisted of no less than seven courses, oysters and turbot in green sauce included, not to mention fine wines and champagne. In 1977 the train ceased to have Istanbul as its final destination and in 2009 the Orient Express disappeared entirely from the time tables. Several other routes continue though and twice a year the historical trip is repeated, at a very stiff price!

Since I couldn’t afford that luxury, I was nevertheless able to relive Orient Express romantic and nostalgia in Istanbul’s Sirkeci gare.

Sirkeci Gare

The pink and white structure of the railway station is located in Eminönü on the shores of the Bosporus. Designed by German architect August Jachmund, it’s the best example of European Orientalism, combining elements of Ottoman architecture with modern amenities such as gas and later electric lighting and heating in winter.

The pink and white structure of the railway station is located in Eminönü on the shores of the Bosporus. Designed by German architect August Jachmund, it’s the best example of European Orientalism, combining elements of Ottoman architecture with modern amenities such as gas and later electric lighting and heating in winter.

As I entered through the elaborate doors, I could well imagine fur clad ladies in pearls and cloches, tripping along the platform, followed by an army of porters bogged down by travel trunks.

They might rest in the Orient Express restaurant, where I sat down for a coffee and a few baklavas and admired the beautiful stained glass windows and Tiffany lamps which still evoke the atmosphere of times gone by.

As I got up to head for the restrooms, I discovered to my delight a tiny museum right next door which is easily overlooked if you don’t know it’s there.

Orient Express Museum

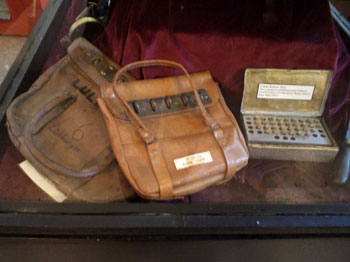

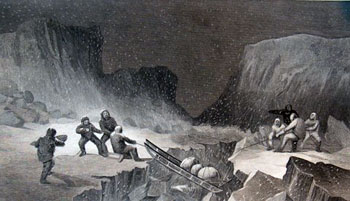

It’s only one room, but the museum documents the history of the Orient Express and the train station in detail. Old log books are displayed as are conductors’ uniforms, the piano, a table laid with the original cutlery and crockery, tickets and many more memorabilia. Photographs adorn the walls and examples of the technology of the time are on display too. I loved the newspaper clipping of when the train got stuck in a snow storm in Bulgaria, very reminiscent of the plot of Agatha’s novel. Admission is free and you are allowed to take as many photographs as you want.

It’s only one room, but the museum documents the history of the Orient Express and the train station in detail. Old log books are displayed as are conductors’ uniforms, the piano, a table laid with the original cutlery and crockery, tickets and many more memorabilia. Photographs adorn the walls and examples of the technology of the time are on display too. I loved the newspaper clipping of when the train got stuck in a snow storm in Bulgaria, very reminiscent of the plot of Agatha’s novel. Admission is free and you are allowed to take as many photographs as you want.

There is just one single guard watching over the treasures and he is happy to answer your questions.

Another Istanbul landmark closely connected to the Orient Express and Srikeci gare is the Pera Palace Hotel.

Pera Palace Hotel

As affluent Europeans started to descend upon romantic Istanbul, using the Orient Express, they needed an equally elegant place to rest their heads. The city was decidedly short of such type of establishment and that’s how the Pera Palace was conceived. The first super luxury hotel of Istanbul, located in fashionable Beyoglu (then called Pera) opened its door with an inaugural ball in 1892.

As affluent Europeans started to descend upon romantic Istanbul, using the Orient Express, they needed an equally elegant place to rest their heads. The city was decidedly short of such type of establishment and that’s how the Pera Palace was conceived. The first super luxury hotel of Istanbul, located in fashionable Beyoglu (then called Pera) opened its door with an inaugural ball in 1892.

Passengers from Sirkeci Gare were carried in sedans all the way up to the Golden Horn and one of these sedans is still displayed in the Pera Palace, next to the elaborate elevator which was the first of its kind in Istanbul. As were other amenities such as hot and cold running water. There are many ‘firsts’ for the Pera Palace, including the first ever fashion show in Istanbul.

Not carried by a sedan but using the tramway running up and down Istaklal Street, I made my way on foot to the Pear Palace. The hotel was closed for nearly four years, undergoing extensive renovations but is now open again. No better place to get a feel for how people traveled in the past than sitting in the Orient Bar, enjoying a cocktail.

Not carried by a sedan but using the tramway running up and down Istaklal Street, I made my way on foot to the Pear Palace. The hotel was closed for nearly four years, undergoing extensive renovations but is now open again. No better place to get a feel for how people traveled in the past than sitting in the Orient Bar, enjoying a cocktail.

Room 411, all decorated in black and red, was Agatha Christie’s favorite room and it was here that she actually wrote her Orient Express mystery. But she isn’t the only famous person having frequented the Pera Palace. Signed photographs of Ernest Hemingway, Greta Garbo, Isadora Duncan and Jackie Kennedy to name but a few look down from the walls. Atatürk was also a frequent visitor, presiding over many a ball.

Even if I wasn’t able to afford a trip on the Orient Express or a stay at the Pera Palace, I could enjoy the atmosphere and easily imagine the past in these three marvelous Istanbul locations, all closely connected to the history of a legendary train.

If You Go:

Istanbul is a city worth a visit any time of the year. However, to avoid tourist crowds and really hot weather, the best seasons are spring and fall. Winters can be quite cold and rainy.

Trains to Greece, the Balkans and beyond still run from Sirkeci Gare. They may not be the Orient Express but you can travel very comfortably in the first class sleepers.

The Pera Palace has an excellent pool, spa and Turkish bath, using products especially made for the hotel in France. A day pass is available for approx. $100, which is a lot less than the average room rate.

About the author:

Inke Piegsa-quischotte is an ex-attorney turned travel writer and novelist. She writes for online travel magazines and has two novels and a travel guide to Galicia/Spain published. She lives between Turkey and Miami. She has just published a book, ‘Istanbul, City of the Green-Eyed Beauty’. Learn more about it here: www.glamourgrannytravels.com

All photographs are by Inke Piegsa-quischotte.

One week didn’t seem like a lot of time, my host at the residency pointed out, after circumstances required I cut my stay by a week. But it turned out to be one of the most productive for my writing in a long time. The residency, located just outside Aureille, provided plenty of uninterrupted time for reading, thinking, and writing, all of which I did copiously.

One week didn’t seem like a lot of time, my host at the residency pointed out, after circumstances required I cut my stay by a week. But it turned out to be one of the most productive for my writing in a long time. The residency, located just outside Aureille, provided plenty of uninterrupted time for reading, thinking, and writing, all of which I did copiously. I spent my second day working on a short story, the concept for which I had been nursing for a while. The entire day, off and on, was spent working on this, and by the evening I was pleased to have finished the first draft. As I lay in bed that night, I contemplated how best to revise and improve my story. Falling asleep, however, did not follow naturally. My hosts keep no locks on their doors, since apparently in Aureille crime is practically unheard of. Unlocked doors always appear like an invitation to trouble for me and I braced the handle of my bedroom door with a chair and kept one of the lights burning to allow me a little peace of mind and some sleep.

I spent my second day working on a short story, the concept for which I had been nursing for a while. The entire day, off and on, was spent working on this, and by the evening I was pleased to have finished the first draft. As I lay in bed that night, I contemplated how best to revise and improve my story. Falling asleep, however, did not follow naturally. My hosts keep no locks on their doors, since apparently in Aureille crime is practically unheard of. Unlocked doors always appear like an invitation to trouble for me and I braced the handle of my bedroom door with a chair and kept one of the lights burning to allow me a little peace of mind and some sleep. That evening the hosts held a dinner for the artists around the pool. They wanted to hear my story that I had unfortunately been unable to present at the conference in Wales, having fallen ill. The warm approval on everyone’s faces and their requests to hear the story I was currently working on at the residency even though it was unpolished told me that perhaps I do have something to offer as a writer.

That evening the hosts held a dinner for the artists around the pool. They wanted to hear my story that I had unfortunately been unable to present at the conference in Wales, having fallen ill. The warm approval on everyone’s faces and their requests to hear the story I was currently working on at the residency even though it was unpolished told me that perhaps I do have something to offer as a writer.

The following morning it was time to leave the residency. As I disposed of the garbage from my apartment, Angela, a Northern Irish artist who was also staying at the residency, was standing outside drinking her morning coffee. She asked me for my last name and thanked me for having shared my short story with the other artists on Saturday evening. “I will look out for your name,” she told me.

The following morning it was time to leave the residency. As I disposed of the garbage from my apartment, Angela, a Northern Irish artist who was also staying at the residency, was standing outside drinking her morning coffee. She asked me for my last name and thanked me for having shared my short story with the other artists on Saturday evening. “I will look out for your name,” she told me.

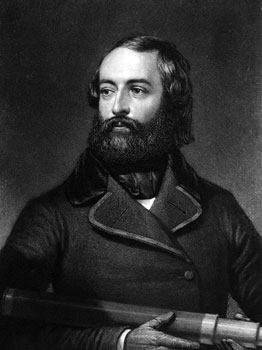

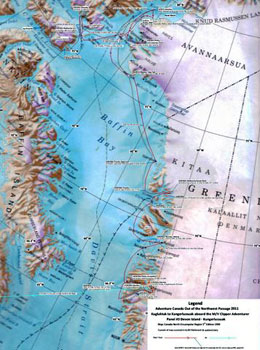

But on September 10, one day after it did so, we sailed into Rensselaer Bay, where in the mid-1850s, explorer Elisha Kent Kane spent two terrible winters trapped in the ice. And three days after that, as on Day Thirteen of our voyage we approached the island town of Upernavik, I went to the bridge. As the staff historian, I needed to announce the surprising news.

But on September 10, one day after it did so, we sailed into Rensselaer Bay, where in the mid-1850s, explorer Elisha Kent Kane spent two terrible winters trapped in the ice. And three days after that, as on Day Thirteen of our voyage we approached the island town of Upernavik, I went to the bridge. As the staff historian, I needed to announce the surprising news. What drove me to the bridge was that our voyage had just become the first to trace Kane’s escape route from Rensselaer Bay to Upernavik, where Danish settlers welcomed the explorer, and now their posterity welcomed us.

What drove me to the bridge was that our voyage had just become the first to trace Kane’s escape route from Rensselaer Bay to Upernavik, where Danish settlers welcomed the explorer, and now their posterity welcomed us. The change gave us extra time. We hoped now to sail north through Smith Sound into Kane Basin. Perhaps we could reach Etah on the west coast of Greenland, situated at a northern latitude of 78 degrees 18 minute 50 seconds. Etah was as far north as Adventure Canada had yet ventured along “the American route to the Pole.”

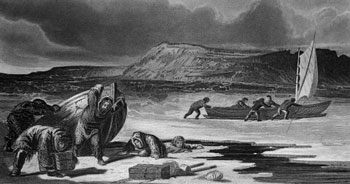

The change gave us extra time. We hoped now to sail north through Smith Sound into Kane Basin. Perhaps we could reach Etah on the west coast of Greenland, situated at a northern latitude of 78 degrees 18 minute 50 seconds. Etah was as far north as Adventure Canada had yet ventured along “the American route to the Pole.” While most voyagers went ashore in zodiacs to explore beaches and ridges, five of us — an archaeologist, a geologist, an artist-photographer, an outdoorsman, and an author-historian (yours truly) — spent three hours searching small rocky islands for relics of Kane’s expedition. We found what I believe to be the remains of his magnetic observatory. And from the zodiac, prevented from scrambling onto slippery rocks by a receding tide, we spotted what I believe to be the site on “Butler Island” where Kane buried the bodies of two of his men.

While most voyagers went ashore in zodiacs to explore beaches and ridges, five of us — an archaeologist, a geologist, an artist-photographer, an outdoorsman, and an author-historian (yours truly) — spent three hours searching small rocky islands for relics of Kane’s expedition. We found what I believe to be the remains of his magnetic observatory. And from the zodiac, prevented from scrambling onto slippery rocks by a receding tide, we spotted what I believe to be the site on “Butler Island” where Kane buried the bodies of two of his men. Ice conditions here have always been difficult and unpredictable. And in recent decades, recorded visits have been few. A 1984 article in Arctic magazine describes a study undertaken by scientists who helicoptered in from the American airbase at Thule to investigate the long-term decline in the caribou population. And an exhaustive archaeological study of northwest Greenland by John Darwent and others, detailed in Arctic Anthropology in 2007, turned up 1,376 features, including winter houses, tent rinks and burials — but sought and discovered no bodies in Rensselaer Bay.

Ice conditions here have always been difficult and unpredictable. And in recent decades, recorded visits have been few. A 1984 article in Arctic magazine describes a study undertaken by scientists who helicoptered in from the American airbase at Thule to investigate the long-term decline in the caribou population. And an exhaustive archaeological study of northwest Greenland by John Darwent and others, detailed in Arctic Anthropology in 2007, turned up 1,376 features, including winter houses, tent rinks and burials — but sought and discovered no bodies in Rensselaer Bay. In Kane’s time, Etah was a permanent Inuit settlement, home to several extended families. Today, it serves as a temporary hunting camp. We stayed six hours and hiked to Brother John Glacier, a natural wonder that Kane, oblivious to Inuit nomenclature, named after his dead sibling.

In Kane’s time, Etah was a permanent Inuit settlement, home to several extended families. Today, it serves as a temporary hunting camp. We stayed six hours and hiked to Brother John Glacier, a natural wonder that Kane, oblivious to Inuit nomenclature, named after his dead sibling. On the Clipper Adventurer, dining variously on Greenland halibut, veal marsala, and braised leg of New Zealand lamb, we retraced Kane’s perilous voyage in two days. We called in at Cape York, where the explorer overcame a last great barrier of protruding shore ice, and from there gazed out over open water.

On the Clipper Adventurer, dining variously on Greenland halibut, veal marsala, and braised leg of New Zealand lamb, we retraced Kane’s perilous voyage in two days. We called in at Cape York, where the explorer overcame a last great barrier of protruding shore ice, and from there gazed out over open water.

After a few days of checking out the architecture in the bustling capital Bucharest, we board a train for Transylvania – one of the largest and most picturesque regions in the centre of Romania known for its historical mix of flavours of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, Saxons and brief Ottoman rule.

After a few days of checking out the architecture in the bustling capital Bucharest, we board a train for Transylvania – one of the largest and most picturesque regions in the centre of Romania known for its historical mix of flavours of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, Saxons and brief Ottoman rule. The Black Church (Biserica Neagra) towers in its dusky beauty in Council Square. Called St. Mary’s from the time the first stone was laid in 1385, until it was renamed in 1689 after its walls were blackened by the “Great Fire” that levelled most of the town. Five richly decorated portals grace the outside. On the inside over 100 Persian rugs are hung from the walls (given to the church by Saxon merchants returning from shopping-sprees to Ottoman lands). In 1839 a 4000-pipe organ was installed. It is a thrill to hear it being played; its thunderous chords setting off tremors in the air waves.

The Black Church (Biserica Neagra) towers in its dusky beauty in Council Square. Called St. Mary’s from the time the first stone was laid in 1385, until it was renamed in 1689 after its walls were blackened by the “Great Fire” that levelled most of the town. Five richly decorated portals grace the outside. On the inside over 100 Persian rugs are hung from the walls (given to the church by Saxon merchants returning from shopping-sprees to Ottoman lands). In 1839 a 4000-pipe organ was installed. It is a thrill to hear it being played; its thunderous chords setting off tremors in the air waves. Vlad III was the ruling prince of the Romanian state of Walachia from 1456-62, and from 1476-77, who offered a strong resistance to the westward expansion by the Ottoman Turks. His moniker Dracula was inherited; it means “son of the dragon” after his father Vlad II Dracul, who was a knight in the Order of the Dragon established to protect Christianity in the land. The symbol of this medieval order was a dragon, or “dracul” which at the time had a positive import, but after the 5th century became a symbol for the Devil. Vlad III’s infamy and his acquired moniker “Tepes” or Impaler, arose from his inhumane method of dealing with his enemies; foreign invaders and also rebellious countrymen, including noblemen (along with their families) who he felt were traitors and conspirators in the death of his father and brother. It is said dozens at one time were skewered on a wooden stakes in such a manner that instead of instant death, the victims suffered excruciating pain for up to 48 hours before their earthly farewell. It is believed that Vlad Tepes never set foot in Bran Castle….but there is a historic mention of his troops passing through Bran in 1459, and if going along on military manoeuvres was the Count’s modus operandi…who knows?

Vlad III was the ruling prince of the Romanian state of Walachia from 1456-62, and from 1476-77, who offered a strong resistance to the westward expansion by the Ottoman Turks. His moniker Dracula was inherited; it means “son of the dragon” after his father Vlad II Dracul, who was a knight in the Order of the Dragon established to protect Christianity in the land. The symbol of this medieval order was a dragon, or “dracul” which at the time had a positive import, but after the 5th century became a symbol for the Devil. Vlad III’s infamy and his acquired moniker “Tepes” or Impaler, arose from his inhumane method of dealing with his enemies; foreign invaders and also rebellious countrymen, including noblemen (along with their families) who he felt were traitors and conspirators in the death of his father and brother. It is said dozens at one time were skewered on a wooden stakes in such a manner that instead of instant death, the victims suffered excruciating pain for up to 48 hours before their earthly farewell. It is believed that Vlad Tepes never set foot in Bran Castle….but there is a historic mention of his troops passing through Bran in 1459, and if going along on military manoeuvres was the Count’s modus operandi…who knows? Built in 1377 it was mainly a fortress over the centuries to protect Romanian borders. In the early 20th century the town of Brasov gave the castle to Queen Marie of Romania. She absolutely loved each of its 57 rooms and she made it a summer retreat for her family of six children and King Ferdinand, when he wasn’t called away with kingly duties. She hired Czech architect, Karel Liman who imparted the castle with its romantic appeal and added to the comfort with heating stoves of Saxon tile, running water, electricity, three telephones and an elevator.

Built in 1377 it was mainly a fortress over the centuries to protect Romanian borders. In the early 20th century the town of Brasov gave the castle to Queen Marie of Romania. She absolutely loved each of its 57 rooms and she made it a summer retreat for her family of six children and King Ferdinand, when he wasn’t called away with kingly duties. She hired Czech architect, Karel Liman who imparted the castle with its romantic appeal and added to the comfort with heating stoves of Saxon tile, running water, electricity, three telephones and an elevator. We make our way up creaky wooden staircases, through narrow passage carved into the rock, and in and out of the high-ceilinged rooms, several of which overlook the courtyard dotted with potted red geraniums to enliven the castle’s sombre tones. Queen Marie’s bedroom and study are restored with ornate hand-carved furnishings, but not in the least opulent. The combined music room and library converted from an old attic is the largest room, and is as cozy as this stone edifice can be with a fireplace, a bear-hide rug and padded furniture.

We make our way up creaky wooden staircases, through narrow passage carved into the rock, and in and out of the high-ceilinged rooms, several of which overlook the courtyard dotted with potted red geraniums to enliven the castle’s sombre tones. Queen Marie’s bedroom and study are restored with ornate hand-carved furnishings, but not in the least opulent. The combined music room and library converted from an old attic is the largest room, and is as cozy as this stone edifice can be with a fireplace, a bear-hide rug and padded furniture.

It is then on to Rasov, well at least to the bottom of the hill where it is perched, as the fortress was closed to renovations. Leaving the town of Rasov, Maxim points and says, “Gypsies”. We pass a rickety canvas-covered wagon pulled by two hefty steeds. A swarthy young man in a wide-brimmed hat jiggles the reins from the driver’s seat. His dark good looks are matched in the gypsy woman we later encounter. Alas, the romanticised lore of the Roma being free-spirited nomads is far from true – strong-spirited would be more fitting.

It is then on to Rasov, well at least to the bottom of the hill where it is perched, as the fortress was closed to renovations. Leaving the town of Rasov, Maxim points and says, “Gypsies”. We pass a rickety canvas-covered wagon pulled by two hefty steeds. A swarthy young man in a wide-brimmed hat jiggles the reins from the driver’s seat. His dark good looks are matched in the gypsy woman we later encounter. Alas, the romanticised lore of the Roma being free-spirited nomads is far from true – strong-spirited would be more fitting.

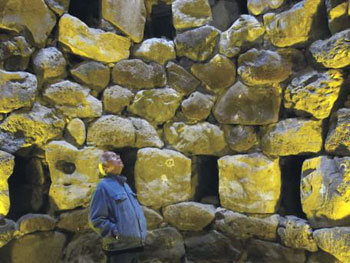

Today, there are more than 8,000 nuraghes still standing from what is estimated to have numbered more than 30,000. They were most prevalent in the northwest and south-central areas of the island and are usually located in a panoramic spot – strategically located on hilltops to control important passages.

Today, there are more than 8,000 nuraghes still standing from what is estimated to have numbered more than 30,000. They were most prevalent in the northwest and south-central areas of the island and are usually located in a panoramic spot – strategically located on hilltops to control important passages.

They all are incredibly accessible and available to explore. When you enter a nuraghe, stand in the middle of the cone and stare up at the opening above you, the presence of it’s former inhabitants is almost palpable. The stone stairs to the various interior levels wind-up the sides of the structure leading to antechambers and strange rooms. There is a strong sense of design and intention.

They all are incredibly accessible and available to explore. When you enter a nuraghe, stand in the middle of the cone and stare up at the opening above you, the presence of it’s former inhabitants is almost palpable. The stone stairs to the various interior levels wind-up the sides of the structure leading to antechambers and strange rooms. There is a strong sense of design and intention. Having stated that, it remains a complete mystery as to who were the Nuragic people. Some clues can be found at The National Archeological Museum in Cagliari. It holds most of the materials discovered in the Nuraghes. They did produce art in the form of beautiful small bronze statues; typically representing Gods, the chief of the village, soldiers, animals and women. There are also stone carvings or statues representing female divinities.

Having stated that, it remains a complete mystery as to who were the Nuragic people. Some clues can be found at The National Archeological Museum in Cagliari. It holds most of the materials discovered in the Nuraghes. They did produce art in the form of beautiful small bronze statues; typically representing Gods, the chief of the village, soldiers, animals and women. There are also stone carvings or statues representing female divinities. The sacred well of Santa Cristina has a hole in the vault. Every 18 and a half years, when the moon reaches is lowest point in orbit, the moonlight strikes the hole and is reflected on the surface of the water. Sunlight is also reflected during the autumn and spring equinoxes. Through these processes we know they possessed a great knowledge of celestial cycles.

The sacred well of Santa Cristina has a hole in the vault. Every 18 and a half years, when the moon reaches is lowest point in orbit, the moonlight strikes the hole and is reflected on the surface of the water. Sunlight is also reflected during the autumn and spring equinoxes. Through these processes we know they possessed a great knowledge of celestial cycles. But that is where the certainties end. Scholars are not even sure of the correct name for the civilization, or even the real meaning of nuraghe. The name itself derives from the meaning of mound and cavity, and the nuraghes are built by laying big stones of similar size on top of each other, leaving a cavity in the middle which is then covered by a stone domed roof. For lack of a more informed identification, scientists accordingly have called them the Nuragic peoples.

But that is where the certainties end. Scholars are not even sure of the correct name for the civilization, or even the real meaning of nuraghe. The name itself derives from the meaning of mound and cavity, and the nuraghes are built by laying big stones of similar size on top of each other, leaving a cavity in the middle which is then covered by a stone domed roof. For lack of a more informed identification, scientists accordingly have called them the Nuragic peoples.