by Connie Pearson

John Cummings, New Orleans attorney, is determined for us to know the real truth about slavery in the South. When blacks and whites are fighting in the streets over the latest injustice, and the whites make the mistake of saying about the blacks, “They just need to get over it,” John Cummings wants us to know what the “it” is. He is dedicating himself and millions of his own money to educating visitors who come to Whitney Plantation, the only plantation in Louisiana with a singular focus on the plight of the slaves.

Thanks in large part to the Federal Writers’ Project which was a part of the WPA (Works Progress Administration created to provide jobs for unemployed Americans after the Great Depression), 2300 individual interviews were recorded with people who were in slavery at the time of the Emancipation Proclamation. Most were children when they were given their freedom but were quite elderly when they told their stories. Interviews were primarily conducted between 1936-1938, but many from Louisiana carried over until 1940. The details and descriptions they shared were chilling. It is unimaginable to believe such inhumanity to man was tolerated, allowed, even culturally accepted.

Thanks in large part to the Federal Writers’ Project which was a part of the WPA (Works Progress Administration created to provide jobs for unemployed Americans after the Great Depression), 2300 individual interviews were recorded with people who were in slavery at the time of the Emancipation Proclamation. Most were children when they were given their freedom but were quite elderly when they told their stories. Interviews were primarily conducted between 1936-1938, but many from Louisiana carried over until 1940. The details and descriptions they shared were chilling. It is unimaginable to believe such inhumanity to man was tolerated, allowed, even culturally accepted.

The exhibits, artwork, tour information and historic buildings on the grounds incorporate slave narratives that represent all victims of slavery in the United States, not just the ones who worked on the grounds of Whitney Plantation. This is a place to remember, to pay respect and to raise awareness. According to an article in The New Yorker by Kalim Armstrong: “The Whitney Plantation is not a place designed to make people feel guilt, or to make people feel shame. It is a site of memory, a place that exists to further the necessary dialogue about race in America.”

The exhibits, artwork, tour information and historic buildings on the grounds incorporate slave narratives that represent all victims of slavery in the United States, not just the ones who worked on the grounds of Whitney Plantation. This is a place to remember, to pay respect and to raise awareness. According to an article in The New Yorker by Kalim Armstrong: “The Whitney Plantation is not a place designed to make people feel guilt, or to make people feel shame. It is a site of memory, a place that exists to further the necessary dialogue about race in America.”

On the plantation grounds, you will find several slave cabins brought in from nearby Myrtle Grove. Twenty-two cabins that existed at Whitney were torn down in 1970, so the present ones are authentic but are not in their original location. The Antioch Baptist Church (formerly known as the Anti-Yoke Baptist Church) has a significant history that you will hear when you tour. Inside are many sculptures created by Woodrow Nash intended to represent slaves of Whitney Plantation as they looked in 1864 when the war ended – as children.

You will see the Field of Angels, which is a memorial dedicated to 2200 slave children who died before their third birthday, and you’ll also pass the Wall of Honor listing the 350 slaves who were actually a part of the Whitney Plantation. Sugar kettles, forged by blacksmiths and representative of the sugar cane production, are scattered throughout the grounds, and occasionally you will hear the sound of a bell. Slaves had no voice, so the bell is rung to symbolically “give them a voice.” Excerpts from the Federal Writers’ Project interviews are inscribed in various locations. Most mention types of punishment used and the rampant sexual exploitation. Here is an example from Julia Woodrich which is less graphic:

You will see the Field of Angels, which is a memorial dedicated to 2200 slave children who died before their third birthday, and you’ll also pass the Wall of Honor listing the 350 slaves who were actually a part of the Whitney Plantation. Sugar kettles, forged by blacksmiths and representative of the sugar cane production, are scattered throughout the grounds, and occasionally you will hear the sound of a bell. Slaves had no voice, so the bell is rung to symbolically “give them a voice.” Excerpts from the Federal Writers’ Project interviews are inscribed in various locations. Most mention types of punishment used and the rampant sexual exploitation. Here is an example from Julia Woodrich which is less graphic:

My ma had fifteen children and none of us had de same pa. Every time she was sold she would get another man. Dey didn’t sell da man dat she would be with. Dey didn’t marry before de war. De missus taken an alphabet or some book and read somethin’ out of it and den put a broom down and dey jump over it, den dey was married. Sometimes dey would give dem a chicken supper.

Swamp land surrounds the plantation, so it is easy to imagine the alligators, snakes and other dangers a slave would have encountered if he tried to run away.

By all means, visit other plantations on River Road, the historic stretch of highway between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. See the gorgeous mansions and learn about life before, during and after the Civil War. But please don’t leave without spending time at Whitney Plantation. It is a vital part of a story that America needs to acknowledge and memorialize.

If You Go:

Whitney Plantation, 5099 Highway 18, Wallace, LA, is open every day except Tuesday from 9:30 to 4:30. Admission is $22.00.

Whitney Plantation, Museum of Slavery and St. Joseph Plantation Tour

Some of the other plantations in the area:

Lodging: Holiday Inn Express, La Place, LA

Dining

- B & C Seafood – Vacherie, LA

- Spuddy’s – Vacherie, LA

- Connie’s Grill – Reserve, LA

- New Orleans Hamburger and Seafood Company – La Place, LA

About the author:

Connie Pearson is a native Alabamian, wife of 46 years, mother of 3 and grandmother of 12. She is a retired elementary music teacher who is now a travel writer and blogger. She is the author of Telling It On the Mountain: 52 Days in the Life of an Improbable Missionary. Visit www.theregoesconnie.com

Photos by Steve Pearson:

Slave cabin

Whitney Plantation sign

Woodrow Nash sculptures inside Antioch Church

Field of Angels

I started my day at Alaska’s oldest and smallest National Park, or as the locals call it, Totem Park, In the center of the park is a commemorative plaque to mark the battle of 1804 between Russia’s Alexander Baranov and the Kiksadi Indians. This decisive battle marked the last major Native resistance in Sitka to European domination of Alaska. A storyboard depicts this historic event. Take special note of the Russian blacksmith hammer shown, the Kiksadi first acquired the hammer as a war prize in their attack on the Russian fort at Old Sitka. The hammer is on display in the Visitor’s Center.

I started my day at Alaska’s oldest and smallest National Park, or as the locals call it, Totem Park, In the center of the park is a commemorative plaque to mark the battle of 1804 between Russia’s Alexander Baranov and the Kiksadi Indians. This decisive battle marked the last major Native resistance in Sitka to European domination of Alaska. A storyboard depicts this historic event. Take special note of the Russian blacksmith hammer shown, the Kiksadi first acquired the hammer as a war prize in their attack on the Russian fort at Old Sitka. The hammer is on display in the Visitor’s Center.

Continue west on Lincoln Street and in a few yards you’ll come to a large sign that marks Castle Hill, also known as Baranof Castle. Tlingits, Russians and Americans have all claimed and occupied this site. First as a lookout point to defend the Tlingit Indian’s home, then Baranof’s Castle was the focal point of the Russian American company and housed the Russian Government and lastly the site where the transfer of Alaska to the United States took place in 1867. This by far is my favorite Russian American site not only because of the historic significance but also of the commanding 360-degree view over the town and water.

Continue west on Lincoln Street and in a few yards you’ll come to a large sign that marks Castle Hill, also known as Baranof Castle. Tlingits, Russians and Americans have all claimed and occupied this site. First as a lookout point to defend the Tlingit Indian’s home, then Baranof’s Castle was the focal point of the Russian American company and housed the Russian Government and lastly the site where the transfer of Alaska to the United States took place in 1867. This by far is my favorite Russian American site not only because of the historic significance but also of the commanding 360-degree view over the town and water.

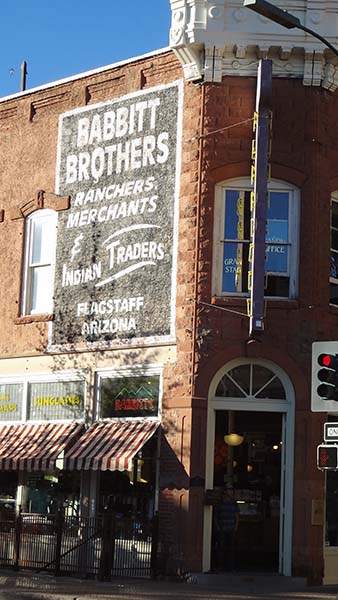

In fifteen minutes I reach the historic center, a memorable assortment of 19th century architecture that is perfect for exploring on foot. There are few specific tourist attractions here, but wandering the hodgepodge of 1890s-era redbrick buildings, many of which flaunt stone and stucco friezes, conjures up visions of the Old West. When the downtown area became rundown in the 1960s, city officials considered demolishing many of the worn structures to build carparks for the increasing numbers of tourists. Thankfully, they realized that if they tore down all the old buildings there would be little reason for tourists to visit.

In fifteen minutes I reach the historic center, a memorable assortment of 19th century architecture that is perfect for exploring on foot. There are few specific tourist attractions here, but wandering the hodgepodge of 1890s-era redbrick buildings, many of which flaunt stone and stucco friezes, conjures up visions of the Old West. When the downtown area became rundown in the 1960s, city officials considered demolishing many of the worn structures to build carparks for the increasing numbers of tourists. Thankfully, they realized that if they tore down all the old buildings there would be little reason for tourists to visit.