San Ángel, Mexico City

by Ellen Johnston

It’s one of the most famous artistic residences on this continent – Frida Kahlo’s “Blue House,” in the old village of Coyoacán, now part of Mexico City. Visitors who might otherwise avoid the grime and congestion of “el Distrito Federal” (as the capital is called) flock here in droves, not only to catch a glimpse of the artist’s life, but also to enjoy the small pleasures of the neighborhood: cobblestone streets, artisan markets, painted tiles, shady public plazas, and blossoms that hang over almost every wall and doorway. It’s a Mexico that feels lost in time, like Frida herself, despite the sprawl of the metropolis that surrounds it. And yet, Coyoacán is not the only part of Mexico City where such an experience can be had. Neighboring San Ángel, less visited and yet equally charming, supplies its own version of a rustic, historic Mexico—and it’s own Frida Kahlo house to boot.

If the Blue House represents the individualism of Frida; her residence of childhood and late adult life (after her split with Diego Rivera), then the San Ángel house stands for what lay in between: her tumultuous marriage. Officially called the “Museo Casa Estudio Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo,” the house is a testament to the couple’s amazing artistic partnership, but also to the deep fissures that drew them apart. Nothing represents this more inherently than the architecture itself, designed by Juan O’Gorman in the revolutionary functionalist style – two houses built into one, linked only by a narrow bridge that runs from rooftop to rooftop.

In San Ángel, the two artists fed, and bled, off each other. Medical problems plagued Frida, and her third pregnancy ended in yet another abortion. Diego had affairs, including one with Frida’s own sister, Cristina, resulting in a temporary separation. But Frida’s artistic and intellectual power also grew during this time, not only thanks to her husband, but also to the circle they drew around them. There, the surrealist André Breton recognized Frida’s talent and offered to show her work in Paris. Not long after, she gave her first solo exhibition at Julien Levy’s gallery in New York City. The San Ángel house was an incubator for both Frida’s talent and her misery. The two went hand in hand, as she painted portrait after portrait of herself in the form of an invalid and scorned woman, sad and withering away just as her star began to grow. Yet, through all this, Frida was slowly, but surely, becoming recognized for something more than her marriage to Diego Rivera. She was an artist in her own right, standing on her own two, albeit crippled, feet.

In San Ángel, the two artists fed, and bled, off each other. Medical problems plagued Frida, and her third pregnancy ended in yet another abortion. Diego had affairs, including one with Frida’s own sister, Cristina, resulting in a temporary separation. But Frida’s artistic and intellectual power also grew during this time, not only thanks to her husband, but also to the circle they drew around them. There, the surrealist André Breton recognized Frida’s talent and offered to show her work in Paris. Not long after, she gave her first solo exhibition at Julien Levy’s gallery in New York City. The San Ángel house was an incubator for both Frida’s talent and her misery. The two went hand in hand, as she painted portrait after portrait of herself in the form of an invalid and scorned woman, sad and withering away just as her star began to grow. Yet, through all this, Frida was slowly, but surely, becoming recognized for something more than her marriage to Diego Rivera. She was an artist in her own right, standing on her own two, albeit crippled, feet.

Though Frida’s feet were certainly not made for walking, the path between her homes in Coyoacán and San Ángel remains, to this day, one of Mexico City’s most beautiful strolls. Avenida Francisco Sosa, which links the two former villages, is lined with colorful old colonial houses, draping gardens, crumbling stone walls and shaded churchyards. The walk takes about 40 minutes, beginning at Coyoacán’s popular Jardín Centenario, and terminating in Plaza San Jacinto, San Ángel’s central square.

Plaza San Jacinto is a popular gathering place, especially on Saturdays, when a giant arts and crafts market, known as El Bazaar Sábado, takes over. It’s a place to buy handcrafted jewelry and ceramics, wooden trinkets and textiles—giving off a flavor that’s a bit more ‘artisanal’ than the art you might find on the walls of Kahlo’s San Ángel house (now a gallery). Not that that’s a bad thing. Handicrafts (known as “artesania”) are a staple of Mexican culture, and influenced Frida greatly. Like Diego Rivera, she strongly believed in the connection between Mexico’s cultural past and its artistic present, and much of her inspiration (in color, dress and style) was derived from the work of the street artists and indigenous people who surrounded her. Many of the objects sold at San Ángel’s Saturday market are timeless, the very same things Frida must have walked past so many years ago: colorful skulls for Día de los Muertos, embroidered blouses, and molcajetes (mortar and pestles) made from the volcanic rock of nearby, smoking, Popocatépetl.

While Plaza San Jacinto is the neighborhood’s most popular outdoor space, the neighboring church (of the same name) provides a much more beautiful and calm place in which to rest. The Iglesia de San Jacinto was built in the 16th century, and feels almost lost in time. Both the building and its garden predate the Great Fire of London, with an architecture and sensibility that might be more at home in Italy, or France, than Mexico. The cloister feels Tuscan, the sanctuary Spanish. The garden is wonderfully wild, almost English in style, hidden behind large stone walls, yet easily accessible through both the church and a stone archway. It’s one of the most serene places in Mexico City, a beautiful spot to rest and contemplate, and begin to understand how truly ancient this country is, even in its colonial manifestations.

While Plaza San Jacinto is the neighborhood’s most popular outdoor space, the neighboring church (of the same name) provides a much more beautiful and calm place in which to rest. The Iglesia de San Jacinto was built in the 16th century, and feels almost lost in time. Both the building and its garden predate the Great Fire of London, with an architecture and sensibility that might be more at home in Italy, or France, than Mexico. The cloister feels Tuscan, the sanctuary Spanish. The garden is wonderfully wild, almost English in style, hidden behind large stone walls, yet easily accessible through both the church and a stone archway. It’s one of the most serene places in Mexico City, a beautiful spot to rest and contemplate, and begin to understand how truly ancient this country is, even in its colonial manifestations.

Would Frida have stopped and rested there from time to time? It’s hard to say. As an atheist, communist and advocate of indigenous culture, she had every reason not to set foot in the garden of a church, even if it was aesthetically pleasing. But Frida also recognized that like Mexico itself, she was the product of multiple heritages: European and Indigenous, Catholic and not. The faces you see in the church’s garden today tell the same story—they are inextricably linked to both sides of the ocean. The church of San Jacinto is a product of colonialism, but it’s also indigenous to the modern-day culture of the mestizo Mexican nation.

Frida’s painting, The Two Fridas, tackles that very same subject, and dates from the years in which she lived in San Ángel. In the double self-portrait, a European Frida holds the hand of an indigenous Mexican version of herself. Even more importantly, their bloodstreams are connected by an artery flowing from heart to heart, bleeding out one end. In many ways, The Two Fridas is about acceptance – of Kahlo’s ancestry, and of Mexico’s—though it’s also about struggle, both in her understanding of her own personal identity, and of her marriage. It’s no accident that Frida needs to hold her own hand in the picture. The Two Fridas was painted just as her marriage was falling apart, and she divorced Diego for the first time.

Frida’s painting, The Two Fridas, tackles that very same subject, and dates from the years in which she lived in San Ángel. In the double self-portrait, a European Frida holds the hand of an indigenous Mexican version of herself. Even more importantly, their bloodstreams are connected by an artery flowing from heart to heart, bleeding out one end. In many ways, The Two Fridas is about acceptance – of Kahlo’s ancestry, and of Mexico’s—though it’s also about struggle, both in her understanding of her own personal identity, and of her marriage. It’s no accident that Frida needs to hold her own hand in the picture. The Two Fridas was painted just as her marriage was falling apart, and she divorced Diego for the first time.

The couple’s San Ángel house is just a short walk away from plaza San Jacinto, northwest through the neighborhood’s winding cobblestone streets. The roads are narrower than those in Coyoacán, and everything is a little bit more hidden, set back behind old stone walls. The Rivera-Kahlo house is a jolt from the norm, modern and airy, with no large fence to block the view. It operates as a museum, with Diego’s side of the house preserved so that you can see what his studio actually looked like, while Frida’s has been turned into an art gallery. The logic behind that decision, besides providing a nice balance of archival, historical information with curated art, comes from the sad truth of the situation. Frida’s side of the house could not be preserved because she left it empty when she moved back to Coyoacán for good. Her things are no longer there, and so rotating exhibits have taken her place, a fitting treatment for a woman who was replaced over and over again by others in Diego’s life.

Despite the tragedy that surrounded their relationship, Frida’s San Ángel house is not an inherently sad place to visit. It’s architecturally interesting, and provides a hands-on, visceral glimpse into the two artists’ lives—a chance to see the furniture, books and giant papier maché dolls that filled Diego’s studio, and the ghosts that are left behind in Frida’s. Outside, tall cactuses grow like relics of a great pre-Columbian past, and purple Jacaranda trees frame Frida’s part of the building, which like her house in Coyoacán is painted a deep, vibrant blue. For all the pain and hardship she endured there, her resilience shines through.

Despite the tragedy that surrounded their relationship, Frida’s San Ángel house is not an inherently sad place to visit. It’s architecturally interesting, and provides a hands-on, visceral glimpse into the two artists’ lives—a chance to see the furniture, books and giant papier maché dolls that filled Diego’s studio, and the ghosts that are left behind in Frida’s. Outside, tall cactuses grow like relics of a great pre-Columbian past, and purple Jacaranda trees frame Frida’s part of the building, which like her house in Coyoacán is painted a deep, vibrant blue. For all the pain and hardship she endured there, her resilience shines through.

San Ángel is a beautiful part of Mexico City that should not be missed by any devotee of Frida Kahlo’s. The house was the centre of her life there, but her inspiration was, and still is, all around. Little shrines can be found on many street corners, built into the walls of gardens. Flower sellers and street vendors perambulate around Plaza San Jacinto, providing colors and flavors to those who are weary of walking. Many nearby artistic institutions can be perused for free. The Soumaya Museum in Plaza Loreto is a highlight, the older (but much smaller) brother of Carlos Slim’s Polanco monolith of the same name. The Museo del Carmen, an old convent just a few blocks east, is also very worthwhile, as are the numerous commercial galleries that line the central square. It’s not the same San Ángel that Frida once knew. It’s too enmeshed with the urban fabric, and there are probably many more tourists these days than there were in her time. But the spirit of the place remains very much there: ancient, indigenous, colonial and new; a mix of them all, like Frida herself.

Frida Kahlo House, Xochimilco, and University City Tour

If You Go:

♦ San Ángel can be easily reached by public transportation. The Metrobus, Mexico City’s Rapid Bus system, makes stops along Avenida Insurgentes, just a few blocks away. The closest stop is called “La Bombilla.” If you’re heading to Coyoacán first, it’s faster to take the Metro, and get off at the Coyoacán stop.

♦ It’s also possible to stay at a hotel in Coyoacán or San Ángel, though most are located more centrally, along Avenida Reforma or in neighbourhoods such as La Condesa and La Roma, about 30 minutes north.

♦ For an extended cultural visit, it’s worth checking out the nearby campus of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, the country’s finest institution of higher learning. A UNESCO heritage site, many of its murals and mosaics were done by famous Mexican artists (including Rivera) and its Ciudad Universitaria (located next to a Metrobus stop of the same name) has many theatres, concert halls and an excellent contemporary art museum.

♦ Good food abounds in both Coyoacán and San Ángel, with fancier tourist-oriented restaurants (and some of the few vegetarian spots in the whole city) located right next to cheap, local fare. Street vendors sell delicious blue-corn Tlacoyos right outside the Coyoacán metro stop, and in the Mercado of San Angel, you can try many local specialties at a very low price.

About the author:

Ellen Johnston is a cultural nomad – a traveller, writer and musician who bounces all over the world. Originally from Vancouver, Canada, she has West Coast roots, a Mediterranean soul and a Chilanga heart, thanks to a recent stint in the Mexican capital. She just returned from her first foray to South America, and will be moving to NYC in the fall to begin an MFA at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. You can find links to her other writing and photography at www.ambiguoustraveller.wordpress.com

All photos by Ellen Johnston.

Our journey to the isle, first recorded as Savary’s Island by Capt. George Vancouver in 1792, began at the ferry dock in Comox, Vancouver Island. An hour twenty later we were rolling off the Queen of Burnaby into Powell River back dropped by the serrated teeth of the majestic coastal mountain range. A half hour north landed us in Lund, a village dating from the 1880s when the two Thulin brothers from Sweden set up shop and named the community after one back home. Free parking is at a premium here but paid parking is available for daily fee of $7.00 at Dave’s parking lot. Savary emerged, a rich green line across the horizon, as we strolled the village boardwalk. Then we were off to our evening abode; a bed and breakfast south of Powell River.

Our journey to the isle, first recorded as Savary’s Island by Capt. George Vancouver in 1792, began at the ferry dock in Comox, Vancouver Island. An hour twenty later we were rolling off the Queen of Burnaby into Powell River back dropped by the serrated teeth of the majestic coastal mountain range. A half hour north landed us in Lund, a village dating from the 1880s when the two Thulin brothers from Sweden set up shop and named the community after one back home. Free parking is at a premium here but paid parking is available for daily fee of $7.00 at Dave’s parking lot. Savary emerged, a rich green line across the horizon, as we strolled the village boardwalk. Then we were off to our evening abode; a bed and breakfast south of Powell River. Stretched along the south shore, where we came ashore, were a line of substantial homes bordering the dirt road which we learned ran the length of the island, about 7.5 kilometres (.8 to 1.5 kilometres wide). Vehicles crowded a haphazard parking lot though few were to be found trundling along the low maintenance dirt roadways with the waning of summer. Admiring homes we walked as far south as the road allowed, drinking in views of beach and mountain. Perhaps appearing a tad bemused as we poured over a brochure we were rescued by a local resident who filled us in on the what’s and wherefore’s of Savary. She and her husband were just closing up their home for the season as were many of the locals; however there are a solid few who call Savary home full time and garner the fruits of civilized solitude in this stunning setting.

Stretched along the south shore, where we came ashore, were a line of substantial homes bordering the dirt road which we learned ran the length of the island, about 7.5 kilometres (.8 to 1.5 kilometres wide). Vehicles crowded a haphazard parking lot though few were to be found trundling along the low maintenance dirt roadways with the waning of summer. Admiring homes we walked as far south as the road allowed, drinking in views of beach and mountain. Perhaps appearing a tad bemused as we poured over a brochure we were rescued by a local resident who filled us in on the what’s and wherefore’s of Savary. She and her husband were just closing up their home for the season as were many of the locals; however there are a solid few who call Savary home full time and garner the fruits of civilized solitude in this stunning setting.

She told us of the Savary Island B & B; a single floor sprawling log building we had just passed and admired. There had been a couple hotels on the island – The Savary, built in 1914 survived until it burned down in 1932 and the Royal Savary Hotel at Indian Point which was demolished in 1982. Now B & Bs, cabin rentals and a lodge offer accommodation options. The listed permanent population of 100 balloons to a couple thousand in the summer.

She told us of the Savary Island B & B; a single floor sprawling log building we had just passed and admired. There had been a couple hotels on the island – The Savary, built in 1914 survived until it burned down in 1932 and the Royal Savary Hotel at Indian Point which was demolished in 1982. Now B & Bs, cabin rentals and a lodge offer accommodation options. The listed permanent population of 100 balloons to a couple thousand in the summer. A black dot on the water proved a large curious seal. Masked Killdeer complained as they wheeled about behind us and, usually solitary, Loons swam about in a group. We wore no watches. Time took on its own rhythm. Afterwards we sat on a log gazing towards the sea and enjoyed a snack. Never ceases to amaze me how food tastes better in such settings.

A black dot on the water proved a large curious seal. Masked Killdeer complained as they wheeled about behind us and, usually solitary, Loons swam about in a group. We wore no watches. Time took on its own rhythm. Afterwards we sat on a log gazing towards the sea and enjoyed a snack. Never ceases to amaze me how food tastes better in such settings. Striking out for the north beach and Mermaid Rock we returned to the dirt road, gloriously titled Vancouver Boulevard, running the spine of the island, and climbed to the height of land which was to take us through a protected and treed sand dunes section, devoid of development due to its fragility. Few cars and people frequented the roadway which felt much like a shady park walk.The takity takity tack of a noisy Piliated woodpecker echoed through the still forest; proving so intent on attacking his tree he took no notice of us. The protected zone is home to 10,000 year old sand dunes. The island is eroding steadily at both the north and south ends.

Striking out for the north beach and Mermaid Rock we returned to the dirt road, gloriously titled Vancouver Boulevard, running the spine of the island, and climbed to the height of land which was to take us through a protected and treed sand dunes section, devoid of development due to its fragility. Few cars and people frequented the roadway which felt much like a shady park walk.The takity takity tack of a noisy Piliated woodpecker echoed through the still forest; proving so intent on attacking his tree he took no notice of us. The protected zone is home to 10,000 year old sand dunes. The island is eroding steadily at both the north and south ends.

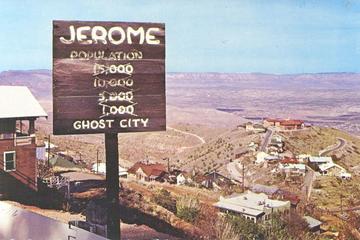

Jerome’s fascinating history began in the 1880s with the arrival of people from many parts of the globe to work the lucrative copper mines that brought its investors billions in profit. In its copper mining heyday, the population of Jerome swelled to over 15,000 and by the 1920s it hailed as the fourth largest territory in the state. Diversions for the miners’ long work hours were many and in the boisterous spirit of the West, lawlessness reigned. A New York newspaper dubbed Jerome “the wickedest city in the West.” The town boasted numerous saloons, Chinese restaurants and laundries and during Jerome’s more decadent times, brothels and bordellos.

Jerome’s fascinating history began in the 1880s with the arrival of people from many parts of the globe to work the lucrative copper mines that brought its investors billions in profit. In its copper mining heyday, the population of Jerome swelled to over 15,000 and by the 1920s it hailed as the fourth largest territory in the state. Diversions for the miners’ long work hours were many and in the boisterous spirit of the West, lawlessness reigned. A New York newspaper dubbed Jerome “the wickedest city in the West.” The town boasted numerous saloons, Chinese restaurants and laundries and during Jerome’s more decadent times, brothels and bordellos. Just as Jerome precariously clings to Cleopatra Hill, the town desperately clung to life. It has survived, despite a long history of tragedy. Fire destroyed large sections of the town on three separate occasions, but Jerome always rebuilt. Devastating landslides and land shifts caused by hundreds of miles of unstable, honeycombed mine shafts under the city itself wrought more damage. An underground blast in 1938 rocked the town’s center, toppling the business district down the mountainside, including the city jail, which slipped 225 feet. Ghostly remains of these structures can still be seen today, some, a hundred yards or more from their original foundations. Untold human tragedies in the form of mining accidents, gunfights, opium overdoses and the flu epidemic killed hundreds. Yet Jerome stubbornly continues to survive.

Just as Jerome precariously clings to Cleopatra Hill, the town desperately clung to life. It has survived, despite a long history of tragedy. Fire destroyed large sections of the town on three separate occasions, but Jerome always rebuilt. Devastating landslides and land shifts caused by hundreds of miles of unstable, honeycombed mine shafts under the city itself wrought more damage. An underground blast in 1938 rocked the town’s center, toppling the business district down the mountainside, including the city jail, which slipped 225 feet. Ghostly remains of these structures can still be seen today, some, a hundred yards or more from their original foundations. Untold human tragedies in the form of mining accidents, gunfights, opium overdoses and the flu epidemic killed hundreds. Yet Jerome stubbornly continues to survive. Over time, the population dwindled to a mere fifty residents and became a virtual ghost town. It was the Jerome Historical Society in the 1960s who saved the town from extinction through its preservation efforts and its proclamation that Jerome was America’s newest and largest ghost city.

Over time, the population dwindled to a mere fifty residents and became a virtual ghost town. It was the Jerome Historical Society in the 1960s who saved the town from extinction through its preservation efforts and its proclamation that Jerome was America’s newest and largest ghost city. In the 1970s small groups of free- spirited artists arrived, restoring abandoned buildings and transforming parts of this ghost town into an arts community. Today, the thriving town with a population of almost 500 is home to quaint bed and breakfasts, restaurants, saloons, art galleries and unique, whimsical boutiques with colorful names evocative of the town’s history, such as Nellie Bly, Ghost City Inn and The Asylum Restaurant. Most of these businesses are located in buildings that date back to the 1800’s, forging an unforgettable link to the town’s storied past. No trip to Jerome is complete without a visit to the Douglas Mansion, home of the Jerome Historic State Park. The interesting exhibits in this stately home bring to life Jerome’s mining heritage and offer a unique glimpse of its glory years.

In the 1970s small groups of free- spirited artists arrived, restoring abandoned buildings and transforming parts of this ghost town into an arts community. Today, the thriving town with a population of almost 500 is home to quaint bed and breakfasts, restaurants, saloons, art galleries and unique, whimsical boutiques with colorful names evocative of the town’s history, such as Nellie Bly, Ghost City Inn and The Asylum Restaurant. Most of these businesses are located in buildings that date back to the 1800’s, forging an unforgettable link to the town’s storied past. No trip to Jerome is complete without a visit to the Douglas Mansion, home of the Jerome Historic State Park. The interesting exhibits in this stately home bring to life Jerome’s mining heritage and offer a unique glimpse of its glory years. At almost a 5,400 feet elevation, Jerome Winery provides astounding views of the Verde Valley that go on forever. Visitors of today wonder if the town’s residents of the past were as awed by its striking vistas. But it is ultimately the sloped buildings perched precariously on the hillsides, dramatic switchback cobblestone streets, and abandoned ruins that the story of Jerome is told. It doesn’t take much to imagine miners walking the streets, hear the tinkling of a piano or the loud, raucous laughter emerging from the saloon and the occasional sounds of gunshots.

At almost a 5,400 feet elevation, Jerome Winery provides astounding views of the Verde Valley that go on forever. Visitors of today wonder if the town’s residents of the past were as awed by its striking vistas. But it is ultimately the sloped buildings perched precariously on the hillsides, dramatic switchback cobblestone streets, and abandoned ruins that the story of Jerome is told. It doesn’t take much to imagine miners walking the streets, hear the tinkling of a piano or the loud, raucous laughter emerging from the saloon and the occasional sounds of gunshots.

In the Cuban Club we climb tiled stairs, woven with ornate wrought-iron railing to the second floor lobby. An expansive area with inviting overstuffed chairs nestle in one corner; plaques honouring past leaders dot the walls. Sunlight splashes through aged curtains lighting the white with gold trim bar. Cane chairs are stacked on the bar’s carved wooden ledge; mirrors behind, fogged and cracked with age.

In the Cuban Club we climb tiled stairs, woven with ornate wrought-iron railing to the second floor lobby. An expansive area with inviting overstuffed chairs nestle in one corner; plaques honouring past leaders dot the walls. Sunlight splashes through aged curtains lighting the white with gold trim bar. Cane chairs are stacked on the bar’s carved wooden ledge; mirrors behind, fogged and cracked with age. Our eager guide escorts us to the two-level 450-seat theater, ballroom, cantina and salon. Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey’s big bands once played in the grand ballroom here. Now it’s primarily a wedding reception venue; not what it once was, but still alive and thriving.

Our eager guide escorts us to the two-level 450-seat theater, ballroom, cantina and salon. Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey’s big bands once played in the grand ballroom here. Now it’s primarily a wedding reception venue; not what it once was, but still alive and thriving. Besides a Cuban social club, Ybor has several others: Italian, Spanish and German. These mutual aid societies provided educational, social and medical services for their ethnic group. Two of them had hospitals; some had boxing and dancing lessons. Tabaqueros (tobacco workers) paid weekly dues for each family member for these services. Social clubs enriched Latinas’ lives during those years.

Besides a Cuban social club, Ybor has several others: Italian, Spanish and German. These mutual aid societies provided educational, social and medical services for their ethnic group. Two of them had hospitals; some had boxing and dancing lessons. Tabaqueros (tobacco workers) paid weekly dues for each family member for these services. Social clubs enriched Latinas’ lives during those years. Continuing along La Septima we amble past storefronts noting a variety of cigars offered: doble robustos, torpedos, Churchills and even orange, coffee and strawberry flavoured. We stop to watch some cigar makers rolling by hand using a cutting board, Chavata (knife) and shaping tools. About one hundred years ago, factories were filled with more than a thousand cigar workers (tabaqueros). The final steps were completed by the highly skilled and well paid torcedores. Lectors read to them to lighten the tedium of the task. Most made decent wages as they were paid by piecework. And, yes, a few women were among these workers.

Continuing along La Septima we amble past storefronts noting a variety of cigars offered: doble robustos, torpedos, Churchills and even orange, coffee and strawberry flavoured. We stop to watch some cigar makers rolling by hand using a cutting board, Chavata (knife) and shaping tools. About one hundred years ago, factories were filled with more than a thousand cigar workers (tabaqueros). The final steps were completed by the highly skilled and well paid torcedores. Lectors read to them to lighten the tedium of the task. Most made decent wages as they were paid by piecework. And, yes, a few women were among these workers.

All this walking wakens our appetite. Lunch is at the oldest restaurant in Florida, the Columbia Restaurant, founded in 1905, the cigar industry’s zenith. This one-of-a-kind eatery consumes a whole city block, contains fifteen dining rooms and a lavish bar worth the visit to see. Patrons line up, some coming on bus tours to enjoy this gem of culinary history. The menu offers a variety of Spanish, Cuban, Italian, and fusion selections: Spanish bean soup, Cuban black bean soup and the award-winning ‘1905 salad’ Columbia’s original, along with a mixto (Cuban sandwich) a multi-cultural mix of ham, roast pork, Swiss cheese and mustard on Cuban bread. A pitcher of Sangria or Mojitos goes well with most menu items. Flamenco dancers perform nightly.

All this walking wakens our appetite. Lunch is at the oldest restaurant in Florida, the Columbia Restaurant, founded in 1905, the cigar industry’s zenith. This one-of-a-kind eatery consumes a whole city block, contains fifteen dining rooms and a lavish bar worth the visit to see. Patrons line up, some coming on bus tours to enjoy this gem of culinary history. The menu offers a variety of Spanish, Cuban, Italian, and fusion selections: Spanish bean soup, Cuban black bean soup and the award-winning ‘1905 salad’ Columbia’s original, along with a mixto (Cuban sandwich) a multi-cultural mix of ham, roast pork, Swiss cheese and mustard on Cuban bread. A pitcher of Sangria or Mojitos goes well with most menu items. Flamenco dancers perform nightly. Another historic building where one can feast is Carne, located in the former El Centro Espanol (Spanish Social Club). A red-bricked edifice with white stones accenting arched windows, hosts this restaurant. Cast iron balconies and a simple, but formidable Moorish-style archway, add to its unique French Renaissance Revival architecture. Now it’s home to shops, businesses and Carne, the restaurant where previously we enjoyed the early bird prime rib dinner and Finlandia Martinis. Both meal and beverage were bargains, generously portioned and palette pleasing.

Another historic building where one can feast is Carne, located in the former El Centro Espanol (Spanish Social Club). A red-bricked edifice with white stones accenting arched windows, hosts this restaurant. Cast iron balconies and a simple, but formidable Moorish-style archway, add to its unique French Renaissance Revival architecture. Now it’s home to shops, businesses and Carne, the restaurant where previously we enjoyed the early bird prime rib dinner and Finlandia Martinis. Both meal and beverage were bargains, generously portioned and palette pleasing.

Rainbow colored piles of bound organic natural and dyed grasses are stacked against the wall. That’s the earthy aroma that meets you at the front door. The rhythmic whir of the foot-pedaled 1900 broom winder clicks and hums as Sam’s deft hands stitch together the layers of broom corn—a kind of sorghum—using a huge double-ended needle that he pushes through the broom. Medieval looking sewing cuffs made of well worn leather with metal disc inserts protect the palms of his hands from a wicked needle jab.

Rainbow colored piles of bound organic natural and dyed grasses are stacked against the wall. That’s the earthy aroma that meets you at the front door. The rhythmic whir of the foot-pedaled 1900 broom winder clicks and hums as Sam’s deft hands stitch together the layers of broom corn—a kind of sorghum—using a huge double-ended needle that he pushes through the broom. Medieval looking sewing cuffs made of well worn leather with metal disc inserts protect the palms of his hands from a wicked needle jab. You don’t usually think of a broom as a thing of beauty, but these brooms are more than that. They’re artful. Functional and long-lasting, their craftsmanship belies the notion that “they sure don’t make things the way they used to” because Sam and Karen’s brooms are made the old-fashioned way, with artistry, attention to detail, and by hand.

You don’t usually think of a broom as a thing of beauty, but these brooms are more than that. They’re artful. Functional and long-lasting, their craftsmanship belies the notion that “they sure don’t make things the way they used to” because Sam and Karen’s brooms are made the old-fashioned way, with artistry, attention to detail, and by hand.

“There’s a romance to this that you don’t find in your computers because computers aren’t fun to watch,” Sam opines. Romance, indeed. And you see what he means when you watch the gears and cogs and wheels and treadles of the cast iron antiquities move with rhythmic simplicity and complexity to create things that people use and need.

“There’s a romance to this that you don’t find in your computers because computers aren’t fun to watch,” Sam opines. Romance, indeed. And you see what he means when you watch the gears and cogs and wheels and treadles of the cast iron antiquities move with rhythmic simplicity and complexity to create things that people use and need. George Rodgers rebuilt the blonde brick building that exists now and bears the name “Rodgers BLK” at the top of it. George died in his upstairs abode in 1901 on the day that President William McKinley was assassinated. The Morrisons say George is a bit of a practical joker. Things seem to move from where they were put. There’s a clinking noise like that of a barrel bolt on the bathroom door every night around 9:00 that causes the cat to startle and hiss. And then, there’s the cigar smoke they get a whiff of every now and then. The Morrisons do not smoke cigars. But there is no fear where George is concerned. Sam and Karen think he’s happy they have the building. He’s become a family friend.

George Rodgers rebuilt the blonde brick building that exists now and bears the name “Rodgers BLK” at the top of it. George died in his upstairs abode in 1901 on the day that President William McKinley was assassinated. The Morrisons say George is a bit of a practical joker. Things seem to move from where they were put. There’s a clinking noise like that of a barrel bolt on the bathroom door every night around 9:00 that causes the cat to startle and hiss. And then, there’s the cigar smoke they get a whiff of every now and then. The Morrisons do not smoke cigars. But there is no fear where George is concerned. Sam and Karen think he’s happy they have the building. He’s become a family friend.

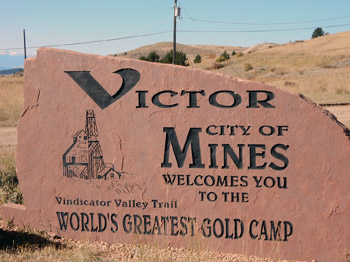

Customers are drawn to the Victor Trading Company by word of mouth and come again and again. The Morrisons do business on a first-name basis and consider their customers close friends. “If we don’t make it, they don’t want it,” Karen says, referring to the fact that people who frequent the store are not interested in any of the factory-made stuff they may have on a shelf or two.

Customers are drawn to the Victor Trading Company by word of mouth and come again and again. The Morrisons do business on a first-name basis and consider their customers close friends. “If we don’t make it, they don’t want it,” Karen says, referring to the fact that people who frequent the store are not interested in any of the factory-made stuff they may have on a shelf or two.