Hazelton, British Columbia

by Glen Cowley

The hills are alive with music in North Central British Columbia. Wending through forests, echoing off mountains and flowing with river and stream; music and song find perfect harmony in a setting inspiring even in its silence.

The Kispiox Valley Music Festival was celebrating its 18th annual birthday but for us it was experience number one. As frequenters of larger weekend music festivals in British Columbia’s more southerly climes we were awakened to the pleasures of a truly laid back experience free from the press of crowds but no less alive in the hum of music and the thrum of audience participation.

Every summer British Columbia comes alive with music festivals. Quite literally you could spend every weekend so entertained. My wife and I regularly favour well known and popular ones such as the Roots and Blues Festival in Salmon Arm and Music Fest at Courtenay on Vancouver Island. Multiple venues, big names, the press of thousands of happy people vying for seating and lineups for food and drink, great music and sense of being part of a vibrant throng will keep us returning year after year.

But there are the smaller festivals which offer something very unique. Kispiox opened our eyes to a new appreciation of the festival experience.

Turning off the Yellowhead Highway (Highway 16) at Hazelton, under the majestic gaze of the Roche de Boule Mountain Range, we journeyed 29 kilometres over breathtaking single lane bridges spanning jaw-dropping gorges and chattering rivers, wending tree-lined ways (largely paved) to emerge at the Kispiox Festival grounds hard by the Kispiox River. On the way we disturbed a solitary black bear strolling leisurely along the road.

Turning off the Yellowhead Highway (Highway 16) at Hazelton, under the majestic gaze of the Roche de Boule Mountain Range, we journeyed 29 kilometres over breathtaking single lane bridges spanning jaw-dropping gorges and chattering rivers, wending tree-lined ways (largely paved) to emerge at the Kispiox Festival grounds hard by the Kispiox River. On the way we disturbed a solitary black bear strolling leisurely along the road.

Colour exploded amid nature’s green and the pulse of music echoed through the trees. Relaxed and friendly volunteers took our admission, which at $60 for the three days (free if you are over 65 or under 12) is a good deal, and directed us to where it was all happening. Varying modes of accommodation filled the camping grounds, divided between “Quiet”, “Very Quiet”, “Musical” and “Performers and Co-ordinators”. Separate venues offered food services and the unique shopping opportunities only festivals afford. The family focus was amply revealed at the children’s area complete with toys, activities and its own entertainment stage.

We arrived at the main River Stage in time to experience the large, colourfully attired, and local Twisted String Band, pumping out lively pieces which had audience members up and dancing while others watched from benches, personal seating or the natural amphitheatre overlooking the stage. The crowd, itself awash in colour, was composed of folk of all ages, hair lengths and attire. Nearby the Hall Stage, housed appropriately in a building with a hall, afforded entertainment free from the warming hand of the Sun.

We arrived at the main River Stage in time to experience the large, colourfully attired, and local Twisted String Band, pumping out lively pieces which had audience members up and dancing while others watched from benches, personal seating or the natural amphitheatre overlooking the stage. The crowd, itself awash in colour, was composed of folk of all ages, hair lengths and attire. Nearby the Hall Stage, housed appropriately in a building with a hall, afforded entertainment free from the warming hand of the Sun.

Set off on its own was the workshop tent where aficionados could meet and learn from performers on a wide range of skills.

Unlike many festivals there was no beer garden though the atmosphere lacked nothing by its absence; indeed the presence of imbibing was apparent but respectfully restricted to non stage areas and revealed no evidence of abuse.

The range of performers covered the bases from children’s’ music, drumming, belly dancing, vaudeville style acts and an eclectic assortment of music provided by both “local” talent and headliners. Such local talent engaged performers from as far away as Prince Rupert and Smithers and was no less impressive in its offerings than the fare provided by headliners.

The 2018 headliners included The Tequila Mockingbird Orchestra, Jacki Treehorn, Fish and Bird from Victoria, multi-faceted CR Avery, the “post-modern Vaudeville duo the Cromoli Brothers, Hannah Epperson, Joanna Chapman-Smith, Jenny Ritter, the Harpoonist and the Axe Murderer, childrens’ performer Angela Brown of the Ta Daa Lady Show, Liron Man playing the hang drum and Bocephus King.

The 2018 headliners included The Tequila Mockingbird Orchestra, Jacki Treehorn, Fish and Bird from Victoria, multi-faceted CR Avery, the “post-modern Vaudeville duo the Cromoli Brothers, Hannah Epperson, Joanna Chapman-Smith, Jenny Ritter, the Harpoonist and the Axe Murderer, childrens’ performer Angela Brown of the Ta Daa Lady Show, Liron Man playing the hang drum and Bocephus King.

A pervasive sense of community permeated the atmosphere – young, old, children, families, First Nations were all well represented and the banter and interaction suggested many knew each other. It felt rather like being in the midst of a large family gathering.

Originally beginning in 1995 with 50 performers and 200 volunteers the festival has grown and now draws over 2000 participants to its fold.

Opening on Friday with a formal welcome by the resident Gitxsan First Nations peoples it ran all day Saturday and terminated with the closing ceremony at 7 pm Sunday. Great music, great atmosphere and great setting equaled a great time.

The Kispiox River chatters by on its forever journey to the sea adding its voice to the heartbeat of the festival, a constant reminder of the pristine beauty and balance of this world. The place and the event are worth time, energy and cost to see and experience. Beauty in nature and humanity does not abide being taken for granted. Hard to believe there are those entertaining pressing a high risk oil pipeline through this land of pristine beauty, purity, vibrant economy and diverse community.

If You Go:

Getting there

By car you are 1:30 hours west from Smithers or 2 hours east from Terrace which are both well served by rail, bus, road and air. Smithers has four flights daily from Vancouver Airport

Services:

There is no readily accessible indoor plumbing on site and it is recommended you bring water, though there is water available on site. There is special washroom access for persons with handicaps to the two existing indoor washrooms. Food services and an outdoor market are available.

Accomodation:

Camping is available on site as well at many off site locations. There are B & B’s throughout the Kispiox Valley as well as in Hazelton.

About the author:

Since 1994 Glen Cowley has parlayed his interest in sports, travel and history into both books and articles. The author of two books on hockey and over fifty published article ( including sports, biographies and travel) he continues to explore perspectives in time and place wherever his travels take him. From the varied landscapes of British Columbia to Eastern Canada and the USA, the British Isles, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Greece and France he has found ample fodder for features. See Glen Cowley’s website at: www.windandice.shawwebspace.ca

All photos by Glen Cowley:

The main stage – River Stage

Spectacular Roche de Boule

Festival Market

Belly Dancer

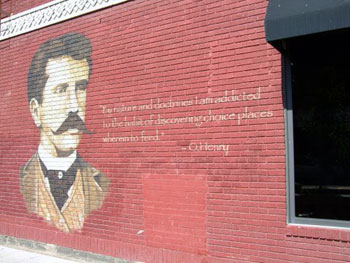

Before moving to Houston to work full-time as a writer for the Houston Post, Porter collected some unique information and experiences in the Texas capital, which later appeared in his works Bexar Scrip No. 2692, Georgia’s Ruling and Gifts of the Magi. Inspired by his work in the Texas General Land Office, Bexar Scrip No. 2692 takes its name from a land grant file that Porter accessed during his daily duties, which had somehow gone astray. In O. Henry’s fictional story, the file goes missing because a rich railroad owner steals it in order to illegally obtain a poor homesteader’s land. Porter’s real-life boss, however, was adamant that such a crime could never have actually occurred, based on the office’s own rules and regulations. Whether you are interested in the historical angle of the document or the writer’s literary take on ordinary events, the original land grant can be viewed online at the Portal to Texas History at

Before moving to Houston to work full-time as a writer for the Houston Post, Porter collected some unique information and experiences in the Texas capital, which later appeared in his works Bexar Scrip No. 2692, Georgia’s Ruling and Gifts of the Magi. Inspired by his work in the Texas General Land Office, Bexar Scrip No. 2692 takes its name from a land grant file that Porter accessed during his daily duties, which had somehow gone astray. In O. Henry’s fictional story, the file goes missing because a rich railroad owner steals it in order to illegally obtain a poor homesteader’s land. Porter’s real-life boss, however, was adamant that such a crime could never have actually occurred, based on the office’s own rules and regulations. Whether you are interested in the historical angle of the document or the writer’s literary take on ordinary events, the original land grant can be viewed online at the Portal to Texas History at  Returning to the O. Henry Museum, visitors can glimpse two more objects that provided inspiration for Porter’s writing. The home showcases two wicker chairs, which were allegedly the inspiration for O. Henry’s best known story, Gifts of the Magi. The author’s wife, Athol, apparently bought him the chairs as a present to decorate their rented home, using money he had saved to purchase her tickets to attend the World’s Fair. Inspired by his wife’s generous act, he wrote the ironic Christmas story in which two lovers buy each other gifts that neither can use, having sold off their most prized worldly possessions in order to pay for the other’s gift. Though the moral is that it’s better to give than to receive, O. Henry’s infamous twist ending provides a bit of dark humor amidst more typical seasonal tales of sharing and caring.

Returning to the O. Henry Museum, visitors can glimpse two more objects that provided inspiration for Porter’s writing. The home showcases two wicker chairs, which were allegedly the inspiration for O. Henry’s best known story, Gifts of the Magi. The author’s wife, Athol, apparently bought him the chairs as a present to decorate their rented home, using money he had saved to purchase her tickets to attend the World’s Fair. Inspired by his wife’s generous act, he wrote the ironic Christmas story in which two lovers buy each other gifts that neither can use, having sold off their most prized worldly possessions in order to pay for the other’s gift. Though the moral is that it’s better to give than to receive, O. Henry’s infamous twist ending provides a bit of dark humor amidst more typical seasonal tales of sharing and caring.

As the vintage blue and white train climbs upstream following the banks of the Arkansas, the canyon walls grow ever closer and higher. Soon a fragile looking suspension bridge comes into view high overhead. It spans the width of the canyon from north to south. From the unobstructed view of an open railroad car, passengers can actually see light between the wooden boards that form the deck of the bridge.

As the vintage blue and white train climbs upstream following the banks of the Arkansas, the canyon walls grow ever closer and higher. Soon a fragile looking suspension bridge comes into view high overhead. It spans the width of the canyon from north to south. From the unobstructed view of an open railroad car, passengers can actually see light between the wooden boards that form the deck of the bridge. Beneath the suspension bridge, the canyon is so narrow and the walls so steep that a place for railroad tracks seemed impossible. The river simply must occupy the entire canyon bottom. But in 1879 a “hanging bridge” was devised and built to allow the tracks to pass through the narrow space suspended above the rushing water. This bridge still serves today.

Beneath the suspension bridge, the canyon is so narrow and the walls so steep that a place for railroad tracks seemed impossible. The river simply must occupy the entire canyon bottom. But in 1879 a “hanging bridge” was devised and built to allow the tracks to pass through the narrow space suspended above the rushing water. This bridge still serves today. It wasn’t a Civil War skirmish; the only one of those fought around here was at Glorietta Pass just south of the New Mexico border. This was a war for territory between two railroads: Colorado’s “baby road,” the narrow gauge, Denver & Rio Grande, and the big, standard gauge, Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe. But, many of the men involved had been soldiers in that bloody war: quite notably the D&RG’s president, General William Jackson Palmer.

It wasn’t a Civil War skirmish; the only one of those fought around here was at Glorietta Pass just south of the New Mexico border. This was a war for territory between two railroads: Colorado’s “baby road,” the narrow gauge, Denver & Rio Grande, and the big, standard gauge, Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe. But, many of the men involved had been soldiers in that bloody war: quite notably the D&RG’s president, General William Jackson Palmer.

Santa Fe seized the entrance to the canyon west of Cañon City cutting off the D&RG for the second time. The outraged D&RG built forts upstream in the canyon to block the rival’s progress. Both sides recruited men well accustomed to the use of firearms – the Santa Fe brought in Bat Masterson with a crew of men from Dodge City. The resulting standoff was widely known as “The Royal Gorge War”.

Santa Fe seized the entrance to the canyon west of Cañon City cutting off the D&RG for the second time. The outraged D&RG built forts upstream in the canyon to block the rival’s progress. Both sides recruited men well accustomed to the use of firearms – the Santa Fe brought in Bat Masterson with a crew of men from Dodge City. The resulting standoff was widely known as “The Royal Gorge War”.

Seymore went on to report Brother Gudmundsen’s birth in Stevanger, Norway on December 11, 1851; that he came to San Francisco in an English ship at the age of seventeen, and followed the sea – as mate of sailing vessels plying between San Francisco and Honolulu. He came to Bremerton in the year 1901 – a skilled workman in the Shipyard – petitioning for and taking the degrees of Freemasonry in the Bremerton Lodge. “We know that he enjoyed the privileges of Lodge membership and that Masonry had meaning for him. Honest his life, faithful his work, peaceful his death,” eulogized Seymore. “And now, my friends, as he lies here so still and silent, these cold lips are teaching us a lesson, if we could but realize it; and that is: to put our house in order, for no man knows when the reaper cometh. With our house in order, we can meet death, not as a grim tyrant, but as a kind friend who has come to give us rest.”

Seymore went on to report Brother Gudmundsen’s birth in Stevanger, Norway on December 11, 1851; that he came to San Francisco in an English ship at the age of seventeen, and followed the sea – as mate of sailing vessels plying between San Francisco and Honolulu. He came to Bremerton in the year 1901 – a skilled workman in the Shipyard – petitioning for and taking the degrees of Freemasonry in the Bremerton Lodge. “We know that he enjoyed the privileges of Lodge membership and that Masonry had meaning for him. Honest his life, faithful his work, peaceful his death,” eulogized Seymore. “And now, my friends, as he lies here so still and silent, these cold lips are teaching us a lesson, if we could but realize it; and that is: to put our house in order, for no man knows when the reaper cometh. With our house in order, we can meet death, not as a grim tyrant, but as a kind friend who has come to give us rest.” Bremerton Cemetery? I remember puzzling over just what had happened to that old pioneer’s cemetery – not enough to do any serious research to find where it had been – but still, more than just idle curiosity – and mystery. Then, this last summer – while aggravating over a traffic revision that forced a detour off of Eleventh Avenue to Naval Avenue – Eureka. There it was: Ivy Green Cemetery, over fifteen picturesque acres of peace, tranquility, history and memories.

Bremerton Cemetery? I remember puzzling over just what had happened to that old pioneer’s cemetery – not enough to do any serious research to find where it had been – but still, more than just idle curiosity – and mystery. Then, this last summer – while aggravating over a traffic revision that forced a detour off of Eleventh Avenue to Naval Avenue – Eureka. There it was: Ivy Green Cemetery, over fifteen picturesque acres of peace, tranquility, history and memories. I strolled among stone lambs, angels and books, crosses, broken columns and scrolls. I found the imposing stone obelisk of Thomas Wren Gorman, born April 12, 1841 at Tulicrimin Kerry County Ireland, died August 31, 1929; and the simple stone of Dr. Carrie E. Logan, PH.D. NYU, “born Mt. Shaster, Calif., 1873-1914 – Daughter of a Union Soldier and a Descendent of a soldier, War of 1812 and the Am. Revolution.” I found Bremerton’s own Tomb of the Unknown Soldier; and the plot dedicated to the Grand Army of the Republic and the final resting place of John H. Nibb, Civil War hero and one the first recipients of the Congressional Medal of Honor. A plot dedicated to U.S. War Veterans of the Spanish American War commemorates veterans of “Cuban, Porto Rico and the Philippine Island campaigns.”

I strolled among stone lambs, angels and books, crosses, broken columns and scrolls. I found the imposing stone obelisk of Thomas Wren Gorman, born April 12, 1841 at Tulicrimin Kerry County Ireland, died August 31, 1929; and the simple stone of Dr. Carrie E. Logan, PH.D. NYU, “born Mt. Shaster, Calif., 1873-1914 – Daughter of a Union Soldier and a Descendent of a soldier, War of 1812 and the Am. Revolution.” I found Bremerton’s own Tomb of the Unknown Soldier; and the plot dedicated to the Grand Army of the Republic and the final resting place of John H. Nibb, Civil War hero and one the first recipients of the Congressional Medal of Honor. A plot dedicated to U.S. War Veterans of the Spanish American War commemorates veterans of “Cuban, Porto Rico and the Philippine Island campaigns.” The fifteen acres were surprisingly easy to cover – and I pretty much visited every grave site, without success. Well – without that particular success. I found the last resting places of many Masons who have gone before. I found sites commemorating Matildas, Cornelias and Getrudes – names once as common as Heather, Kimberly and Keisha may be today. I found Woodmen of the World, and I found Leda Nelson, born September 20, 1838, died September 20, 1902, “A little time on earth she spent, Til God for her his angels sent,” and little Baby Hope, October 5, 1904—March 30, 1905, “Jesus’ Little Lamb.”

The fifteen acres were surprisingly easy to cover – and I pretty much visited every grave site, without success. Well – without that particular success. I found the last resting places of many Masons who have gone before. I found sites commemorating Matildas, Cornelias and Getrudes – names once as common as Heather, Kimberly and Keisha may be today. I found Woodmen of the World, and I found Leda Nelson, born September 20, 1838, died September 20, 1902, “A little time on earth she spent, Til God for her his angels sent,” and little Baby Hope, October 5, 1904—March 30, 1905, “Jesus’ Little Lamb.” But still no Brother Gudmundsen—until I ran into City of Bremerton Parks Department Specialist Chris Smith. After a brief consultation with the Register, Chris led me to RI 962, Lot 08, North Side and there, just below the Pederson Column and an inch from the stone border of another family plot, was a modest stone marker, maybe 18 inches by six inches – much eroded and defaced by time: 1851___Gudmund ____en ____19___. Brother Gudmundsen died just days after his 56th birthday, and was respectfully interred through the disinterested friendship of his brother Masons over one hundred years ago. The acacia tree was long gone, but the grave marker remains, weathered—but readable.

But still no Brother Gudmundsen—until I ran into City of Bremerton Parks Department Specialist Chris Smith. After a brief consultation with the Register, Chris led me to RI 962, Lot 08, North Side and there, just below the Pederson Column and an inch from the stone border of another family plot, was a modest stone marker, maybe 18 inches by six inches – much eroded and defaced by time: 1851___Gudmund ____en ____19___. Brother Gudmundsen died just days after his 56th birthday, and was respectfully interred through the disinterested friendship of his brother Masons over one hundred years ago. The acacia tree was long gone, but the grave marker remains, weathered—but readable.

In Ogunquit the attraction of the Maine coastline with its powerful, relentless sea is no better advertised. The long marshy estuary of the Ogunquit River is a tended conservation area playing home to the restoration of endangered wildlife while at the same time a secluded and quiet finger of tranquility hidden behind the long sand bar facing the pounding Atlantic.

In Ogunquit the attraction of the Maine coastline with its powerful, relentless sea is no better advertised. The long marshy estuary of the Ogunquit River is a tended conservation area playing home to the restoration of endangered wildlife while at the same time a secluded and quiet finger of tranquility hidden behind the long sand bar facing the pounding Atlantic. Perkins Cove housed all the trappings of a tourism centre, its protected harbor filled with a broad assortment of sea craft from sailing vessels to fishing boats. At the end of the sheltering peninsula a village of restaurants and gift shops wound along a narrow street. A salt water taffy shop tempted us, and more than a few others, with bin after bin of differing flavours .

Perkins Cove housed all the trappings of a tourism centre, its protected harbor filled with a broad assortment of sea craft from sailing vessels to fishing boats. At the end of the sheltering peninsula a village of restaurants and gift shops wound along a narrow street. A salt water taffy shop tempted us, and more than a few others, with bin after bin of differing flavours . The commercial centre of Ogunquit, stretched in large part along Shore Road and Main Street, suggests a community taking pride in itself and its environment. Gardens, well kept homes, sea views and a lighted downtown evening atmosphere complimented the well cared for beach, estuary and Marginal Way. Ogunquit is much more than a summer holiday land or Kodak moment.

The commercial centre of Ogunquit, stretched in large part along Shore Road and Main Street, suggests a community taking pride in itself and its environment. Gardens, well kept homes, sea views and a lighted downtown evening atmosphere complimented the well cared for beach, estuary and Marginal Way. Ogunquit is much more than a summer holiday land or Kodak moment. No trip to Maine would be complete without a visit to Kennebunkport and a drive by of the Bush’s summer home where we joined others snapping pictures of the home of two US presidents. Even without a peak at the primary attraction there were lots of other spots to visit along the winding seacoast or in the small town of Kennbunkport where the tides leave exposed naked pier pylons supporting an array of buildings like some fishing village of old.

No trip to Maine would be complete without a visit to Kennebunkport and a drive by of the Bush’s summer home where we joined others snapping pictures of the home of two US presidents. Even without a peak at the primary attraction there were lots of other spots to visit along the winding seacoast or in the small town of Kennbunkport where the tides leave exposed naked pier pylons supporting an array of buildings like some fishing village of old.