Moving from History to Legend Through Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo

by Anastasia Klimchynskaya

On the 24th of February, 1815, the lookout of Notre-Dame de la Garde signaled the three-master, the Pharaon, from Smyrna, Trieste, and Naples.”

Thus begins Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo, telling of the arrival of the ship Pharaon (bearing the novel’s protagonist, Edmond Dantes) into Marseille. By a strange coincidence, I arrive in Marseille on the 25th of February, almost exactly two centuries later. I had vowed to visit this sacred place ever since I’d read Alexandre Dumas’ novel at an impressionable young age – – and finally, here I am.

The Count of Monte Cristo is Dumas’ sweeping tale of love, betrayal, and, above all, revenge. But it is also the story of transformation, both of its protagonist, Edmond Dantes, and of the reader – and at the center of that story of transformation figures the Chateau d’If. Mentioned in a deceptive, throwaway line on the first page, as the Pharaon passes by it on its way into port, the island fortress comes to play a significant and symbolic role in the novel: imprisoned there for fourteen years, Edmond Dantes escapes through the means of a faked death, his symbolic resurrection transforming him into the eponymous Count of Monte Cristo and allowing him to pursue his revenge.

His transformation had, in a way, been mine as well. For The Count of Monte Cristo, despite its cliffhangers and breathless moments, also possesses a stunning ability to see into the essence of the human soul, and at my tender age of thirteen, it had become that story which, read in one’s youth, becomes the transformative tale that first gives one some understanding of the nature of the world. It was the novel that had spurred me to pursue a career of studying literature, and now, as a student of French literature studying abroad in France, I came to make a pilgrimage to the birthplace of the fictional character who had played a role in that transformation, and set me on the path I was to follow.

So far, I followed almost exactly in the footsteps of Edmond Dantes, but perhaps it would be just as fitting to say that I was following in the footsteps of Dumas. An avid traveler, Dumas wrote as widely as he journeyed, inspired both by the places he visited as by the stories, legends, and history he collected on his travels. The world was his plaything, an endless well of opportunities to transform history and reality into fiction; everywhere he went, words and stories sprang forth, until the original sources had become obscured by the wild, sweeping stories of intrigue, suspense, and humanity that he penned. Marseille was no exception; Dumas visited the town on numerous occasions, treading where his literary creation had supposedly walked and using it as fodder for his story. Dumas always had a knack for hanging the romance over the reality – a sterner reality that hits me square in the face as I emerged from the Marseille metro.

So far, I followed almost exactly in the footsteps of Edmond Dantes, but perhaps it would be just as fitting to say that I was following in the footsteps of Dumas. An avid traveler, Dumas wrote as widely as he journeyed, inspired both by the places he visited as by the stories, legends, and history he collected on his travels. The world was his plaything, an endless well of opportunities to transform history and reality into fiction; everywhere he went, words and stories sprang forth, until the original sources had become obscured by the wild, sweeping stories of intrigue, suspense, and humanity that he penned. Marseille was no exception; Dumas visited the town on numerous occasions, treading where his literary creation had supposedly walked and using it as fodder for his story. Dumas always had a knack for hanging the romance over the reality – a sterner reality that hits me square in the face as I emerged from the Marseille metro.

Here, as I mount the steps from the metro to the street, a bustle of cars and trams, the blinding light of the sun, and the shouts of the fish-sellers hit me squarely in the face. And yet there’s also a novelistic charm to the quay where I emerge; two centuries may have passed, but the feel of an important port town is almost the same as in Dumas’ day: the smell of salt and sea, the wind whipping my hair, the sellers of fish haggling, the busy fish market with its clusters of boats, their tall masts rising proudly to the sky like a forest of leafless trees.

My first order of business is to find a ferry.

This also happened to be almost exactly what Dumas had done – except that in his day one did not take ferries. Instead, standing on the quay, he demanded the first available boat, only to watch a transaction between two boatmen as one quite obviously purchased Dumas as a passenger from the other.

This also happened to be almost exactly what Dumas had done – except that in his day one did not take ferries. Instead, standing on the quay, he demanded the first available boat, only to watch a transaction between two boatmen as one quite obviously purchased Dumas as a passenger from the other.

Dumas recounts how he attempted to reimburse his boatman for his own price, only to be informed “No, Monsieur Dumas, you don’t pay.” At his surprise at being recognized, the boatman replied, “If I didn’t know you, I wouldn’t have bought you.” As much as Dumas attempted to pay, the man refused, informing Dumas “You’re our breadwinner, with your Monte Cristo novel. We really should give you a pension for all the fares you provide for us from those who want so go to the Chateau d’If!”

Soon I’m on the ferry, my hair blowing in the salty breeze as I watch the harbor fade away beyond me. Looking back, I wonder if Edmond Dantes also looked back on his native city as he was taken away to the Chateau d’If. Did he watch it shrink and be lost from sight, thinking he might never see it again? It’s only belatedly that I remember that, indeed, Dantes looked back, seeing the light shining in the window of his beloved one last time. Did Dumas, too, on his trip, wonder about the fate that he’d condemned his protagonist to?

Finally, we approach the island harboring over the fortress, and I look over the side eagerly, recalling the foreboding words from the novel:

Finally, we approach the island harboring over the fortress, and I look over the side eagerly, recalling the foreboding words from the novel:

Dantes …saw rise within a hundred yards of him the black and frowning rock on which stands the Chateau d’If. This gloomy fortress, which has for more than three hundred years furnished food for so many wild legends, seemed to Dantes like a scaffold to a malefactor.”

True to his Romantic roots, Dumas’ description was properly gloomy, atmospheric and terrifying. It’s little like the impression I have, as I first glimpse the fortress and then step off the ferry onto the rock landing, breathing in the smell of salt and sea. The sun shines down, the fresh seawater lapping against the rocks. It’s early spring, not yet quite warm, but not cold either; above all, though, it’s the kind of weather that reminds me of warm summer vacations. Much like any reader of Dumas, I’ve allowed the story to overshadow reality, hoping to see a dark fortress on a stormy night.

I mount the craggy steps hopefully and enter eagerly, only to be confronted by a squat building of yellow stone, square in its shape and with short, stubby towers at each corner. The fortress itself is small centerpiece on the craggy island surrounding it, the ground around it pebbly and barren.

When I walk into the edifice itself, the first thing I chance upon is the gift shop, packed full of Dumas novels in a variety of languages, biographies of the author, musketeer figurines, and quills and ink, and again I’m confronted with Dumas’ uncanny ability to bring his creations to life in such a way that the lines between fiction and reality, history and story, legend and truth, are blurred. In his heyday – the heyday of the French Romantic novel, published in the newspapers – his fiction was enormously popular, the equivalent of the bestsellers today. Much like Arthur Conan Doyle, who, decades later, would be unable to escape the onslaught of letters addressed to “Sherlock Holmes,” Dumas too was inundated with enthusiasm for characters he’d invented, with readers traveling to the places where his characters had “lived” and adventured, mindless of the difference between fictional people and real ones.

The first time Dumas visited the Chateau d’If, he was a tourist as much as I, but rather than paying homage to a literary monument, he was visiting a historical one. Originally built in the 16th century by King Francis I to defend France from the sea, it had once been a military stronghold, then a prison. Set on an island off the coast of southern France, it was ideal for holding political prisoners from the various revolutions France experienced in the 19th century. During Dumas’ first visit, in fact, its claim to fame was that it had once housed Mirabeau, a writer, orator, and statesman from the time of the French Revolution.

But when Dumas returned, several decades later, after he’d become a famous novelist, all he saw here was the traces of this novel. This second time, he went incognito, such that the concierge told him the story of his own protagonist. Dumas admits that absolutely nothing was missing from the tale of Dantes’ escape as recounted by the unknowing man. When he left, Dumas presented the concierge with a certificate stating that his summary conformed perfectly to the novel itself.

Two hundred years later, little has changed. The shadow of Dumas’ story – and his marketability – hangs over every inch of the monument the way it did two hundred years ago, obscuring its historical significance. Stepping inside, I find myself in the courtyard of the fortress, and my first care is to find the “cell” of the Edmond Dantes – the same one, probably, that Dumas himself was shown as he was recounted the tale of his famous fictional prisoner. Blithely ignoring the historical reality that states that Dantes didn’t actually exist, everything here is rendered as closely to the novel as possible.

Two hundred years later, little has changed. The shadow of Dumas’ story – and his marketability – hangs over every inch of the monument the way it did two hundred years ago, obscuring its historical significance. Stepping inside, I find myself in the courtyard of the fortress, and my first care is to find the “cell” of the Edmond Dantes – the same one, probably, that Dumas himself was shown as he was recounted the tale of his famous fictional prisoner. Blithely ignoring the historical reality that states that Dantes didn’t actually exist, everything here is rendered as closely to the novel as possible.

The cell itself is large, brightly lit with an electric light that illuminates every nook and cranny, but I have no doubt that with the door locked and the electric light shut off, the dark and windowless room would be a cold, lonely, gloomy prison. I run my fingers along the thick stone walls, wondering what it would be like to spend several decades here, with nothing but these walls and cold floor for company. Insanity seems like a likely outcome, and a quest for revenge even more so. There’s even a passageway dug between this cell and a neighboring one, that of the Abbe Faria – another of Dumas’ characters, the one who helped Dantes escape and taught him everything he’d need to know for his revenge. According to Dumas, it was already there on his visit a century and a half ago. It didn’t matter that there had been no Edmond Dantes or Abbe Faria; his spirit lingered there.

Having explored the cell itself, I wander around the rest of the chateau, climbing its three stories to the rooftop and gazing at far-off Marseille on the coast. Then I wander the rocky, barren island, passing the half-hour until the next ferry arrives to take visitors back. Lost in thought, I venture into the tall, wild grasses to gaze down at the sheer drop into the sea. Despite the warm sun illuminating the scene, there’s a hopelessness to these barren crags. Standing at the very edge, I reminisce about how Edmond Dantes escaped by being thrown into that very water as he played dead and wonder if perhaps I’d picked the exact spot from which they had thrown his body into the depths, unwittingly allowing him to escape.

Having explored the cell itself, I wander around the rest of the chateau, climbing its three stories to the rooftop and gazing at far-off Marseille on the coast. Then I wander the rocky, barren island, passing the half-hour until the next ferry arrives to take visitors back. Lost in thought, I venture into the tall, wild grasses to gaze down at the sheer drop into the sea. Despite the warm sun illuminating the scene, there’s a hopelessness to these barren crags. Standing at the very edge, I reminisce about how Edmond Dantes escaped by being thrown into that very water as he played dead and wonder if perhaps I’d picked the exact spot from which they had thrown his body into the depths, unwittingly allowing him to escape.

As I take the ferry back to Marseille, my mind is equally lost in thought. Around me, tourists are enjoying sun and sea, seemingly unaware that such great literary adventures had happened just off the coast. But for me, this place is all about the book. When Dumas reread his own works on his deathbed, he admitted that he preferred The Three Musketeers to The Count of Monte Cristo – but, respectfully, I disagree. It is the Count who dropped into my life in the shape of a book, telling me a bittersweet story of being human – and, somehow, carefully, subtly, informing me of the way of the world. He’s the one that brought me to France, to study French literature in the same Paris where most of it was birthed. It is the nature of Dumas’ works that they simultaneously overshadow reality and capture its essence – and the fact that his story had taken me on a journey of thousands of miles to follow in the footsteps of a character who had only walked here in myth and fiction is testament to that fact.

Marseille Shore excursion: Private Full-Day tour in Aix en Provence – winery and Cassis

If You Go:

The Chateau d’If is located on a small island off the coast of Marseille in the south of France. Marseille can be easily reached by train or plane; to reach the island itself, you will need to take a ferry from the Old Port (Vieux Port). The ferries run multiple times a day and stop at several islands, including the Chateau d’If. Check the ferry schedules online ahead of time and bring a schedule with you so that you can time your visit to fit in between ferry departures (a suggested time to visit the fortress and island thoroughly is an hour). Tickets for entry to the fortress can only be purchased upon arrival at the island. The fortress is open every day during high season and every day except Monday during low season, but keep an eye on the weather – the ferries might not run due to inclement weather. Ferry schedules, fortress hours, ticket prices, and other details can be checked at the fortress’ website.

About the author:

Anastasia Klimchynskaya is a graduate student in literature and an avid traveler, two passions she combines into literary travel. She believes travel should be as adventurous as the books she brings along on the trip with her, and writes about her literary travel adventures in her blog at itinerantbookworm.wordpress.com.

Photo Credits:

Isle d’If Chateau and Marseille by Jan Drewes (www.jandrewes.de) / CC BY-SA

The Chateau d’If by Anastasia Klimchynskaya

Sign pointing to the cell of the ‘Count of Monte Cristo’ by Anastasia Klimchynskaya

A view of the fortress from the ferry by wpopp / CC BY-SA3

Faraway view of the fortress – Philippe Alès / CC BY-SA

The inside of the Count’s cell – Ask Nine / CC0

View of Marseille from the ferry by Anastasia Klimchynskaya

History, as it’s studied in school, can be a tough concept to wrap your head around. Centuries can be covered in days; weeks can be spent on one event. For many, the time when prehistoric man was living and roaming the caverns and fields and mountains of the Earth gets scrambled with the era of the dinosaurs. I had a hard time figuring out a real timeline when I was in high school history class. In fact, it’s only been in living history, in exploring the places where these things actually took place, pressing my hand against the wall of a building that once witnessed a revolution, a king’s court dance, a meeting of the French Resistance, that I’ve been able to understand, even a little bit, the events, the moments, the people that came before me.

History, as it’s studied in school, can be a tough concept to wrap your head around. Centuries can be covered in days; weeks can be spent on one event. For many, the time when prehistoric man was living and roaming the caverns and fields and mountains of the Earth gets scrambled with the era of the dinosaurs. I had a hard time figuring out a real timeline when I was in high school history class. In fact, it’s only been in living history, in exploring the places where these things actually took place, pressing my hand against the wall of a building that once witnessed a revolution, a king’s court dance, a meeting of the French Resistance, that I’ve been able to understand, even a little bit, the events, the moments, the people that came before me. But somehow, prehistory is harder to get a grasp on. How can you look at a place and imagine nothing, none of the buildings or houses or even roads, none of the modernity that seems to exist wherever you go today? It’s difficult, near impossible, and yet I found it much easier to wrap my head around the prehistory as I journeyed through Southern France.

But somehow, prehistory is harder to get a grasp on. How can you look at a place and imagine nothing, none of the buildings or houses or even roads, none of the modernity that seems to exist wherever you go today? It’s difficult, near impossible, and yet I found it much easier to wrap my head around the prehistory as I journeyed through Southern France. Tautavel Man is a 450,000-year-old fossil, a proposed subspecies of Homo erectus, one of our true ancestors. I find it incredibly hard to fathom the time between when he was born and when I was, and yet that’s the point of the museum in the town of Tautavel, which explores the discoveries uncovered in the cave and offers a unique view of life in this region at Tautavel Man’s time.

Tautavel Man is a 450,000-year-old fossil, a proposed subspecies of Homo erectus, one of our true ancestors. I find it incredibly hard to fathom the time between when he was born and when I was, and yet that’s the point of the museum in the town of Tautavel, which explores the discoveries uncovered in the cave and offers a unique view of life in this region at Tautavel Man’s time.

The museum is split into two portions: the first is in the village and offers an exploration of the tools and shelters created by Tautavel man and his contemporaries. Visiting this portion of the museum first allows you to experience some of the wonder that the first archaeologists excavating in the cave above did.

The museum is split into two portions: the first is in the village and offers an exploration of the tools and shelters created by Tautavel man and his contemporaries. Visiting this portion of the museum first allows you to experience some of the wonder that the first archaeologists excavating in the cave above did. The museum is ideal for visits with kids, complete with activities in the summer including teaching participants how to throw a spear or make fire out of stones and moss. But even for adults, these activities are essential to gaining a true glimpse of life in the time of Tautavel Man.

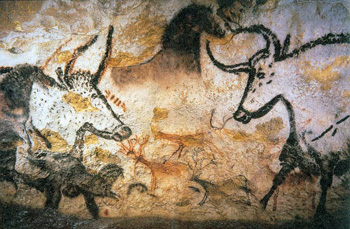

The museum is ideal for visits with kids, complete with activities in the summer including teaching participants how to throw a spear or make fire out of stones and moss. But even for adults, these activities are essential to gaining a true glimpse of life in the time of Tautavel Man. It is in Lascaux that, in 1940, three local teenagers accidentally stumbled upon prehistoric cave paintings, changing the way that we perceive of these “cave” men forever. Soon after their discovery, experts identified the paintings as Paleolithic art, some of the earliest to have ever been discovered. The paintings are far more recent than Tautavel man, at 17,300 years old, and they have long been a draw to this region, not far from Limoges, where art still remains an important element of local life due to the tradition of Limoges porcelain.

It is in Lascaux that, in 1940, three local teenagers accidentally stumbled upon prehistoric cave paintings, changing the way that we perceive of these “cave” men forever. Soon after their discovery, experts identified the paintings as Paleolithic art, some of the earliest to have ever been discovered. The paintings are far more recent than Tautavel man, at 17,300 years old, and they have long been a draw to this region, not far from Limoges, where art still remains an important element of local life due to the tradition of Limoges porcelain.

I went to Lascaux to visit the caves, but like all visitors since the 1960s, I actually visited Lascaux II, a replica of the original cave, which was closed when experts realized that lichen had become prevalent due to the frequency of visits and risked destroying the paintings. But visiting Lascaux II is not discouraging; after buying our tickets in the village of Montignac below and driving up to the caves, we are taken on a journey through time.

I went to Lascaux to visit the caves, but like all visitors since the 1960s, I actually visited Lascaux II, a replica of the original cave, which was closed when experts realized that lichen had become prevalent due to the frequency of visits and risked destroying the paintings. But visiting Lascaux II is not discouraging; after buying our tickets in the village of Montignac below and driving up to the caves, we are taken on a journey through time. The guide goes into details that never would have occurred to me over the next 45 minutes: how the paints were made by the artist, who shows considerable skill in representing the animals that existed around him including horses, cattle and stags. As we wander through the caves, I almost forget that this is a facsimile, until the guide explains the feat of reproducing the caves using a concrete base and the recreation of the same sorts of paints that would have been used for the originals. Lascaux II is accurate up to a couple of millimeters to the original.

The guide goes into details that never would have occurred to me over the next 45 minutes: how the paints were made by the artist, who shows considerable skill in representing the animals that existed around him including horses, cattle and stags. As we wander through the caves, I almost forget that this is a facsimile, until the guide explains the feat of reproducing the caves using a concrete base and the recreation of the same sorts of paints that would have been used for the originals. Lascaux II is accurate up to a couple of millimeters to the original.

by Christine Sarikas

by Christine Sarikas  Years later, on the eve of my next trip to France, a friend I was meeting sent me an e-mail that contained three words: Château de Fontainebleau? Some quick research told me Fontainebleau was a palace used by French royalty, about 45 minutes from Paris. I was skeptical, feeling that visiting would mean long lines and vast car parks, but my friend insisted, so to Fontainebleau we went.

Years later, on the eve of my next trip to France, a friend I was meeting sent me an e-mail that contained three words: Château de Fontainebleau? Some quick research told me Fontainebleau was a palace used by French royalty, about 45 minutes from Paris. I was skeptical, feeling that visiting would mean long lines and vast car parks, but my friend insisted, so to Fontainebleau we went.

A château first stood on the site during the 12th century and served as a hunting lodge for the kings of France. In 1169, Thomas Becket, the exiled Archbishop of Canterbury, consecrated the site’s chapel to the Virgin Mary and Saint Saturnin. Numerous French kings visited and expanded the château, and in December of 1539, Fontainebleau, by then far larger and more luxurious than a simple hunting lodge, played host to Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. His son, Henry II of France, was a frequent visitor, and Henry’s wife Catherine de Medici gave birth to six of their children within the château. Hunting parties continued to be held at Fontainebleau, marriages were arranged and conducted, a peace treaty between France and England was signed on 16 September 1629, and over a century later Louis XVI signed a trade agreement with England, effectively signaling the end of the American Revolutionary War. Monarchs, royals, and heads of state all visited the château, but Fontainebleau’s most famous resident did not arrive until 1803.

A château first stood on the site during the 12th century and served as a hunting lodge for the kings of France. In 1169, Thomas Becket, the exiled Archbishop of Canterbury, consecrated the site’s chapel to the Virgin Mary and Saint Saturnin. Numerous French kings visited and expanded the château, and in December of 1539, Fontainebleau, by then far larger and more luxurious than a simple hunting lodge, played host to Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. His son, Henry II of France, was a frequent visitor, and Henry’s wife Catherine de Medici gave birth to six of their children within the château. Hunting parties continued to be held at Fontainebleau, marriages were arranged and conducted, a peace treaty between France and England was signed on 16 September 1629, and over a century later Louis XVI signed a trade agreement with England, effectively signaling the end of the American Revolutionary War. Monarchs, royals, and heads of state all visited the château, but Fontainebleau’s most famous resident did not arrive until 1803. Napoleon first visited the Château de Fontainebleau to inspect the newly finished military academy, École Spéciale Militaire. By the beginning of the 19th century, the château had fallen into disrepair; the vast majority of its furnishings had been sold during the French Revolution, and Fontainebleau was left empty and neglected. Napoleon chose to leave Versailles–with its Bourbon links–vacant and instead turned his attention to transforming Fontainebleau once again into a home and symbol of power.

Napoleon first visited the Château de Fontainebleau to inspect the newly finished military academy, École Spéciale Militaire. By the beginning of the 19th century, the château had fallen into disrepair; the vast majority of its furnishings had been sold during the French Revolution, and Fontainebleau was left empty and neglected. Napoleon chose to leave Versailles–with its Bourbon links–vacant and instead turned his attention to transforming Fontainebleau once again into a home and symbol of power.

Less widely known and visited than Versailles, Fontainebleau still offers the same degree of beauty and splendor. Its long history and renovations by generations of rulers has meant that Fontainebleau’s sprawling palace showcases examples of French architecture from the 12th to 19th centuries. Its most defining feature is its grand horseshoe staircase, commissioned by Louis XIII (who was born in the palace) and built by Jean Androuet du Cerceau. The majority of the château’s current buildings were constructed in the 14th century under Francis I, whose architect Gilles de Breton created much of the Cour Ovale, the château’s oldest and most central courtyard.

Less widely known and visited than Versailles, Fontainebleau still offers the same degree of beauty and splendor. Its long history and renovations by generations of rulers has meant that Fontainebleau’s sprawling palace showcases examples of French architecture from the 12th to 19th centuries. Its most defining feature is its grand horseshoe staircase, commissioned by Louis XIII (who was born in the palace) and built by Jean Androuet du Cerceau. The majority of the château’s current buildings were constructed in the 14th century under Francis I, whose architect Gilles de Breton created much of the Cour Ovale, the château’s oldest and most central courtyard. Fontainebleau, with its combination of Italian and French artistic styles, is considered by many to be the birthplace of the Renaissance within France. Much of the palace reflects the Italian Mannerist style, popular during the later years of the Renaissance and now widely known as the “Fontainebleau style.” The palace’s Gallery of Francis I, which is dominated by Florentine artist Rosso Fiorentino’s series of frescoes, was the first large decorated gallery to be created in France. Other Renaissance painters who contributed to the art at Fontainebleau include Francesco Primaticcio and Benvenuto Cellini; the latter’s Nymph of Fontainebleau is now housed at the Louvre.

Fontainebleau, with its combination of Italian and French artistic styles, is considered by many to be the birthplace of the Renaissance within France. Much of the palace reflects the Italian Mannerist style, popular during the later years of the Renaissance and now widely known as the “Fontainebleau style.” The palace’s Gallery of Francis I, which is dominated by Florentine artist Rosso Fiorentino’s series of frescoes, was the first large decorated gallery to be created in France. Other Renaissance painters who contributed to the art at Fontainebleau include Francesco Primaticcio and Benvenuto Cellini; the latter’s Nymph of Fontainebleau is now housed at the Louvre.

The landscape here is flat, and has been farmed – and fought over – for centuries. Tilled land spreads in all directions, dotted by the occasional stone farmhouse, a church spire, a copse of trees. Shrapnel from the war still surfaces each season as the fields are farmed. The heavy soil stuck to my shoes, and all too easily turns to mud. A confusion of back roads loop and intersect through small villages, where horse-drawn carts are still in use.

The landscape here is flat, and has been farmed – and fought over – for centuries. Tilled land spreads in all directions, dotted by the occasional stone farmhouse, a church spire, a copse of trees. Shrapnel from the war still surfaces each season as the fields are farmed. The heavy soil stuck to my shoes, and all too easily turns to mud. A confusion of back roads loop and intersect through small villages, where horse-drawn carts are still in use. Beneath the Hôtel de Ville is an entrance to the Boves, or medieval tunnels. The origin of the name is uncertain; however, from the 10th century limestone was quarried here, until the practice was moved outside the city amidst fears the town would collapse. The tunnels run along five different levels, at times up to twenty meters deep. Most of the buildings on Le Place des Héros have their own entrance, now used mainly as cellars or for storage (and an exquisite restaurant, La Faisanderie, perfect after a day touring the battlefields).

Beneath the Hôtel de Ville is an entrance to the Boves, or medieval tunnels. The origin of the name is uncertain; however, from the 10th century limestone was quarried here, until the practice was moved outside the city amidst fears the town would collapse. The tunnels run along five different levels, at times up to twenty meters deep. Most of the buildings on Le Place des Héros have their own entrance, now used mainly as cellars or for storage (and an exquisite restaurant, La Faisanderie, perfect after a day touring the battlefields).

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial encompasses a 250 acre battlefield park, which includes the area of the Battle of Vimy Ridge (9th April, 1917). Both Allied and German trenches have been preserved, and it is still possible to walk along them. The trenches never ran in a straight line, and had alcoves at regular intervals for shelter from bombs and snipers. Some barbed-wire stakes remain; earlier ones with only one hole, and a later design which could hold three stands of barbed wire. These also had the advantage of having a screw on the base, allowing them to be silently screwed into the heavy soil, and not hammered.

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial encompasses a 250 acre battlefield park, which includes the area of the Battle of Vimy Ridge (9th April, 1917). Both Allied and German trenches have been preserved, and it is still possible to walk along them. The trenches never ran in a straight line, and had alcoves at regular intervals for shelter from bombs and snipers. Some barbed-wire stakes remain; earlier ones with only one hole, and a later design which could hold three stands of barbed wire. These also had the advantage of having a screw on the base, allowing them to be silently screwed into the heavy soil, and not hammered.