by Angela Lapham

Berlin is such a vibrant city with so much history that I’ve included it in all my trips to Europe. What’s more, it’s a springboard for several other fascinating not so far away destinations in the former East Germany…

23 minutes on the train and I’m walking across the Glienicke Bridge, the site of many a Cold War spy exchange. Next I’m touring the palace where the famous Potsdam Conference took place between Truman, Stalin and Churchill, discussing the future of Europe following WWII.

DRESDEN

Two hours from Berlin, Dresden is celebrated for its Old Town, beautifully restored after being destroyed in WWII. Its New Town, I discover, is equally intriguing. A hippy area full of street art, live music and conviviality, I start to wonder if I’ve gone to a music festival! Be sure to check out ‘Kunsthofpassage’: five apartment block courtyards that have become huge art installations (Located at Görlitzer Str. 21-25).

Two hours from Berlin, Dresden is celebrated for its Old Town, beautifully restored after being destroyed in WWII. Its New Town, I discover, is equally intriguing. A hippy area full of street art, live music and conviviality, I start to wonder if I’ve gone to a music festival! Be sure to check out ‘Kunsthofpassage’: five apartment block courtyards that have become huge art installations (Located at Görlitzer Str. 21-25).

Likewise, Dresden has some fairly alternative museums. The ‘German Hygiene Museum’ traces the, at times disturbing though more often amusing, history of twentieth century public healthcare education in Germany. ‘The World of the GDR‘ uses mannequins to depict everyday life in Communist East Germany. And the Museum of Military History confronts such themes as war-induced psychological trauma, animals used in battle, military inspired fashion and toys, and the valuable contributions made by individuals who committed themselves to community instead of military service (compulsory in Germany until 2011).

LEIPZIG

Captivating museums can also be found in Leipzig, another city two hours from Berlin (and famed for its classical composers Bach, Mendelssohn and Wagner). Runde Ecke exposes the former headquarters of the Communist government’s secret police (Stasi) and Zeitgeschichtliches Forum explores everyday life in Communist East Germany and the subsequent reunification process. Throughout the city, signs trace the history of the resistance movement against the government, which ultimately led to the fall of the Berlin Wall. I leave Leipzig with a strong sense of what East Germans went through.

CHEMNITZ

An hour’s drive/train from Dresden and Leipzig, industrial Chemnitz has not enjoyed anywhere near the same level of redevelopment and as such offers a glimpse into what life was like in Communist East Germany. Of course the 13 meter, 40 ton Karl Marx bust on its main street, Brückenstraße, does little to dispel the image either! Erected following Chemnitz’s 1953 name change to ‘Karl Marx State,’ Marx had no particular connection to the city – a Communist nation commemorating the seventieth anniversary of his death was reason enough!

Any doubts I’d had over whether to make the trip to Chemnitz evaporated as soon as I saw the size of the intricately detailed spectacle before me. What a breathtaking testament to the power of ideology!

This feeling only intensifies when, walking down Brückenstraße (to the left of Marx), I unexpectedly bump into the most artistically unusual Communist-era monuments I’ve seen traveling Eastern Europe. Cubic-structured friezes depict pre-Communist scenes of class inequality, Lenin with soldiers and industrial workers, and Marx and Engels alongside an overjoyed proletariat.

This feeling only intensifies when, walking down Brückenstraße (to the left of Marx), I unexpectedly bump into the most artistically unusual Communist-era monuments I’ve seen traveling Eastern Europe. Cubic-structured friezes depict pre-Communist scenes of class inequality, Lenin with soldiers and industrial workers, and Marx and Engels alongside an overjoyed proletariat.

Walking away from Marx’s head in the opposite direction, I chance upon the ‘Park of the Victims of Fascism’ (Bundesstraße174) and, in it, another Marx and Engels. Across the park, a large building catches my eye – partly because it’s quite grand, and partly because it’s decorated in nude male statues. Male statues also frame the doorway. Engaged in scholarly pursuits they signify what is the oldest school in Chemnitz (est.1857).

East German history is also on show at Chemnitz’s new, very impressive ‘Museum of Industry’ documenting 220 years of fashion, cars, electrical appliances, ceramics, and mining.

Some products enjoyed huge international success, such as furniture and home-wares created by the Bauhaus School of Art & Design. Attractive as well as functional, these epitomized the Bauhaus objective to preserve artistic design in an era of mass manufacturing.

Nevertheless, as the museum shows, reunification of Germany in 1989 caused a long list of East German companies to go into liquidation because they couldn’t compete with their West German counterparts.

Still, some companies survived, like Germany’s oldest chocolate company, Halloren, a thirty minute train ride from Leipzig in…

HALLE SALE

At Halloren I have the opportunity to sample the entire chocolate truffle range and to buy test products before they’re released to the public.

Meanwhile, the museum contains huge chocolate sculptures of Halle Saale buildings (including the Halloren founder’s office!), emanating the most intoxicating aroma, and a fascinating exhibition detailing the company’s history.

Meanwhile, the museum contains huge chocolate sculptures of Halle Saale buildings (including the Halloren founder’s office!), emanating the most intoxicating aroma, and a fascinating exhibition detailing the company’s history.

Halloren proves particularly interesting as a case study on the failings of Communism. An excellent video explains the factory never reached its quotas and that it was common practice to exaggerate these – ‘Everyone played the game.’ Corruption and lack of profit motive left the factory in a state of continual disrepair, which would have seen it end with Communism – had it not been for a buyer appreciating its potential. Likewise, shortages under Communism meant the company was always substituting more expensive ingredients for cheaper vegetable-based ones. I suddenly realize why a proportion of their range is unintentionally vegan!

Halle Saale also has a Beatles museum, the death mask belonging to Martin Luther (on display at ‘Markt’ Church, where he gave the occasional sermon), and a classical music museum in the childhood home of composer George Frideric Handel.

WEIMAR

An hour by train from Halle Saale or Leipzig, Weimar was the focal point of the enlightenment in Germany. It was also the birthplace of the most influential art movement of the twentieth century, Bauhaus, that this year celebrated its centenary and moved its extensive collection of artworks and artifacts to a new, purpose-built exhibition space.

The Bauhaus School of Art & Design became the Bauhaus University. It, together with the Franz Liszt University of Music, gives Weimar a very ‘university town feel’ – fitting, considering the intellectual climate established there by such writing greats as Johann Wolfgang Goethe and Friedrich Schiller. Both were attracted to Weimar in the 1770s when Duchess Anna Amalia, a big supporter of the arts and education, opened one of Germany’s first public libraries, now known as the ‘Anna Amalia Bibliothek.’ Goethe later became the director of this exquisitely decorated library, and he and other great thinkers are immortalized in busts and portraits to inspire each coming generation.

The Bauhaus School of Art & Design became the Bauhaus University. It, together with the Franz Liszt University of Music, gives Weimar a very ‘university town feel’ – fitting, considering the intellectual climate established there by such writing greats as Johann Wolfgang Goethe and Friedrich Schiller. Both were attracted to Weimar in the 1770s when Duchess Anna Amalia, a big supporter of the arts and education, opened one of Germany’s first public libraries, now known as the ‘Anna Amalia Bibliothek.’ Goethe later became the director of this exquisitely decorated library, and he and other great thinkers are immortalized in busts and portraits to inspire each coming generation.

Both here and in all of Weimar’s cultural institutions an audio device provides self-guided tours in English.

Germany’s oldest literature archive, the Goethe and Schiller Archive, is also in Weimar. Architecturally beautiful, it has a spectacular view of the city, built on a hill to better protect it in the event of fire.

There’s more to see, however, inside the archive of renowned philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche.

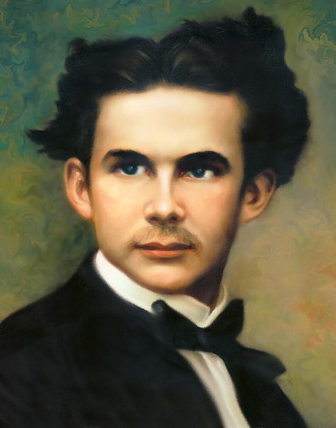

Nietzsche’s sister turned their last home into a shrine to him, erecting a statue and gold letter ‘N’ in the lounge room and holding lectures and literary teas in his memory. On display is the honorary doctorate he was awarded at twenty five and the first two pages of the original manuscript of his first work, ‘The Birth of Tragedy.’

ROCKEN

Nietzsche was buried where he was born, in a miniscule village 23 minutes’ drive from Leipzig, in front of the church where his father served as local pastor. Behind the church a sculpture depicts both a famous photo of Nietzsche with his mother and a vision he once had where he attended his own funeral twice. I freely wander the grounds and inside the church, during which time I see not a single tourist or even the church’s caretaker.

*Nietzsche’s childhood home can also be visited, in the nearby town of Naumberg (For me it was a very quick visit on account of all the displays being in German!). There is a very touching Nietzsche statue in Naumberg too, on Holzmarkt Square.

One could say a trip through Eastern Germany is an education in everything: from philosophy to literature, to music, art and architecture, to the consequences that political and economic upheaval brings. The bonus is that total travel time for the above trip is less than 9 hours by train. Throw in nearby Prague as well!

If You Go:

Berlin Multi-Day Tour: Discover Berlin in 4 Days With Private Airport Transfer

About the author:

Angela is a Melbourne-based librarian and history graduate fascinated with Eastern Europe and different cultures and histories in general. Every few years it’s time to take off to Europe for another lengthy adventure.

Photos by Angela Lapham

I had come to Bavaria for the Oberammergau Passion Play. On the day of my unanticipated detour I woke up planning to explore the picturesque village where I was staying. But dark grey clouds hid the peaks of the nearby mountains threatening rain, and it was obviously a day to head indoors.

I had come to Bavaria for the Oberammergau Passion Play. On the day of my unanticipated detour I woke up planning to explore the picturesque village where I was staying. But dark grey clouds hid the peaks of the nearby mountains threatening rain, and it was obviously a day to head indoors.

As it turned out, the tour was absolutely captivating. I had accidentally discovered Schloss Linderhof, built by Bavaria’s “mad” King Ludwig II between 1869 and 1886. I had never heard of King Ludwig but discovered that he was one of history’s great eccentrics. He was a fascinating study in contrasts. He was a shy and sensitive soul trained from birth for a very public royal role. He was a petty vassal owing allegiance to Prussia who, because he was born on the day Louis IX was canonized, felt an almost mystical connection to the great French House of Bourbon. He was also a modern constitutional monarch with very limited powers who wished he could have been one of history’s absolute rulers.

As it turned out, the tour was absolutely captivating. I had accidentally discovered Schloss Linderhof, built by Bavaria’s “mad” King Ludwig II between 1869 and 1886. I had never heard of King Ludwig but discovered that he was one of history’s great eccentrics. He was a fascinating study in contrasts. He was a shy and sensitive soul trained from birth for a very public royal role. He was a petty vassal owing allegiance to Prussia who, because he was born on the day Louis IX was canonized, felt an almost mystical connection to the great French House of Bourbon. He was also a modern constitutional monarch with very limited powers who wished he could have been one of history’s absolute rulers. The tour started in the vestibule, an elegant space decorated with rose marble pillars which pays tribute to the Sun King. Our guide then led us through a series of rooms, each more opulent than the last, to Ludwig’s massive bedroom where he slept in an enormous four poster bed covered in royal blue, gold-trimmed velvet.

The tour started in the vestibule, an elegant space decorated with rose marble pillars which pays tribute to the Sun King. Our guide then led us through a series of rooms, each more opulent than the last, to Ludwig’s massive bedroom where he slept in an enormous four poster bed covered in royal blue, gold-trimmed velvet.

For King Ludwig, the Venus Grotto was much more than a simple escape from the rain. It was a total escape from reality. The King, it seems, was quite a patron of the arts. He commissioned private theatrical and musical performances in his very own theatre. He was also a great admirer and major sponsor of the great composer Richard Wagner, and the Venus Grotto was a man-made cave, a private retreat where Ludwig could enjoy Wagner’s music in blissful solitude.

For King Ludwig, the Venus Grotto was much more than a simple escape from the rain. It was a total escape from reality. The King, it seems, was quite a patron of the arts. He commissioned private theatrical and musical performances in his very own theatre. He was also a great admirer and major sponsor of the great composer Richard Wagner, and the Venus Grotto was a man-made cave, a private retreat where Ludwig could enjoy Wagner’s music in blissful solitude. Marie-Antoinette was guillotined for the excesses of Bourbon royalty. Ludwig’s end, although more prosaic, was also a consequence of his profligate lifestyle. It also holds a tantalizing element of mystery.

Marie-Antoinette was guillotined for the excesses of Bourbon royalty. Ludwig’s end, although more prosaic, was also a consequence of his profligate lifestyle. It also holds a tantalizing element of mystery.

It was the second week of December and I sat on the train from Munich to Salzburg with the intention to visit the Austrian Christmas market and to do some shopping. The sky was blue, snowflakes were falling softly, dusting the dense pine forest on both sides of the line.

It was the second week of December and I sat on the train from Munich to Salzburg with the intention to visit the Austrian Christmas market and to do some shopping. The sky was blue, snowflakes were falling softly, dusting the dense pine forest on both sides of the line. Actually, no sign was needed. I only had to follow the wafting scents of Gluehwein and Bratwurst and the sounds of Bavarian horns and German Christmas carols to find the market.

Actually, no sign was needed. I only had to follow the wafting scents of Gluehwein and Bratwurst and the sounds of Bavarian horns and German Christmas carols to find the market. I got lucky insofar as I was the only visitor, the majority of people were enjoying the market and its delights, something which I reserved for later. The lady who sold me the ticket and acted as curator was so pleased to have something other to do other than sit at her desk, that she personally lead me around and told me story after story about the customs and traditions of this part of Bavaria.

I got lucky insofar as I was the only visitor, the majority of people were enjoying the market and its delights, something which I reserved for later. The lady who sold me the ticket and acted as curator was so pleased to have something other to do other than sit at her desk, that she personally lead me around and told me story after story about the customs and traditions of this part of Bavaria. The 16th century wardrobes, carved with the finest details, are called Chavari and were used to store a bride’s trousseau. One such chavari is kept in the museum and filled with traditional clothing as well as examples of another art: gold embroidery. Bridal headgear and lace is made from real gold thread, an art which my friendly guide herself is skilled in, as proven by a growing strip of gold lace which she was working on whilst waiting for visitors.

The 16th century wardrobes, carved with the finest details, are called Chavari and were used to store a bride’s trousseau. One such chavari is kept in the museum and filled with traditional clothing as well as examples of another art: gold embroidery. Bridal headgear and lace is made from real gold thread, an art which my friendly guide herself is skilled in, as proven by a growing strip of gold lace which she was working on whilst waiting for visitors. Plenty of visitors were around, but it felt rather like a huge family. Everybody seemed to know everybody else and as soon as they noticed that I wasn’t ‘einheimisch’, they explained the specialties to me and directed me to the stalls with the Rauschgoldengel and other beautiful Christmas decorations.

Plenty of visitors were around, but it felt rather like a huge family. Everybody seemed to know everybody else and as soon as they noticed that I wasn’t ‘einheimisch’, they explained the specialties to me and directed me to the stalls with the Rauschgoldengel and other beautiful Christmas decorations. Next was Dampfnudel, which literally translated means steam nudel but has nothing to do with pasta or steam. It’s a huge lump of sweet dough, covered with vanilla custard, whipped cream and chocolate sauce. I could never have managed one on my own, but my new best friends from Prien, standing next to me and putting the sweet away in incredible amounts, gave me a spoon and let me have a few mouthfuls.

Next was Dampfnudel, which literally translated means steam nudel but has nothing to do with pasta or steam. It’s a huge lump of sweet dough, covered with vanilla custard, whipped cream and chocolate sauce. I could never have managed one on my own, but my new best friends from Prien, standing next to me and putting the sweet away in incredible amounts, gave me a spoon and let me have a few mouthfuls.