by George Fery

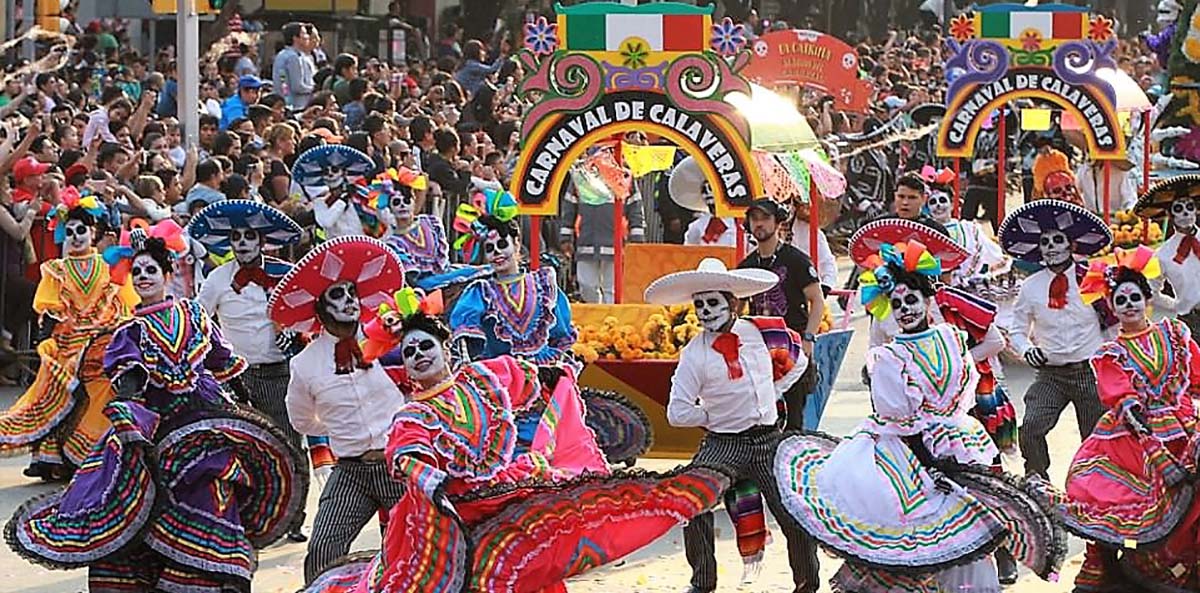

The celebrated Mexican national holyday, Dia de Muertos (its original name in Spanish), or Day of the Dead, means one thing for city dwellers and quite another for country folks. It is a day to have “fun” and the joyful remembrance of departed family members. The joy is for those the ancestors left behind, the life enjoyed by the descendants.

This family affair take place over two days, traditionally the 1st and 2nd day of November. The 1st day celebrates the dead children and young adults souls; it is called the Day of the Little Angel, or Day of the Innocents, when the family bring small toys and tears to the grave. The 2nd day is the Dia de Muertos also referred to as Dia de los Difuntos, dedicated to adults. In the Americas ancestor worship is a tradition that spans thousands of years.

In Mexico, on the first day in the afternoon, altars with ofrendas, or offerings, are set up in homes, businesses and public places. The offerings honor adults that passed away, a testimony of their contribution to family life. The heart of the symbolic meaning of ofrendas is for the people, while the altar is dedicated to saints of the creed. They are typically made up of seven levels, representing the layers through which souls are believed to travel to reach the underworld, before ascending to paradise.

In Mexico, on the first day in the afternoon, altars with ofrendas, or offerings, are set up in homes, businesses and public places. The offerings honor adults that passed away, a testimony of their contribution to family life. The heart of the symbolic meaning of ofrendas is for the people, while the altar is dedicated to saints of the creed. They are typically made up of seven levels, representing the layers through which souls are believed to travel to reach the underworld, before ascending to paradise.

A profusion of flowers to attract the souls of the dead, is the hallmark of the Dia de los Muertos, among which is the yellow Marigold called cempuazutchil in nahualt, the Aztec language that means “twenty flowers”; in ancient times the celebration took place in August. The red Cockscomb and the white Baby’s Breath are for the clouds, among others. The yellow color is for the earth, white for heaven. The color purple, together with the smoke of copal incense is to attract visiting spirits.

In cities, for the first two days of remembrance, family members attend church service and pray for the souls of those family members that passed away. They then visit the cemetery to clean and freshen up the grave, made of a slab and a small structure with a cross, or that of another creed. At such time it is customary to eat and drink with the ancestor, in a bitter-sweet memory.

In cities, for the first two days of remembrance, family members attend church service and pray for the souls of those family members that passed away. They then visit the cemetery to clean and freshen up the grave, made of a slab and a small structure with a cross, or that of another creed. At such time it is customary to eat and drink with the ancestor, in a bitter-sweet memory.

In small towns such as Pomuch, Estado Campeche, the Day of the Dead in the Maya-Yucatec language is called Hanal Pixan, that means “Food for the Souls”. The local custom call for the bones of the ancestors to be housed in small colorful concrete mausoleums. In the structure are small wood crates, about 2’x3’x2’, into which are saved the bones of selected ancestors. As a rule, the box is lined with a fine hand embroidered cloth, with the name of the departed or a short allegorical sentence.

This tradition is very much alike that of ancient second burial practices found in many cultures throughout the world, well documented in the Americas. The primary burial address the decomposition of soft tissues of the body. After several months, once decomposition is complete, the bones are removed, cleaned and saved in a separate but permanent setting. Of note is that not all past progenitors qualify as ancestor, only those lineage members that left a significant impact on resource acquisition or lineage alliance are worthy of being venerated.

This tradition is very much alike that of ancient second burial practices found in many cultures throughout the world, well documented in the Americas. The primary burial address the decomposition of soft tissues of the body. After several months, once decomposition is complete, the bones are removed, cleaned and saved in a separate but permanent setting. Of note is that not all past progenitors qualify as ancestor, only those lineage members that left a significant impact on resource acquisition or lineage alliance are worthy of being venerated.

During the visit, the bones are removed one at a time from the wood box by the descendants while praying or “speaking” to the deceased. The bones are then gently cleaned with a light brush, then returned to the box lined up with a freshly hand embroidered cloth, until next year’s Hanal Pixan ceremony, and for the departed anniversary passing day.

During the visit, the bones are removed one at a time from the wood box by the descendants while praying or “speaking” to the deceased. The bones are then gently cleaned with a light brush, then returned to the box lined up with a freshly hand embroidered cloth, until next year’s Hanal Pixan ceremony, and for the departed anniversary passing day.

In more traditional villages, such as at San Juan Chamula, Estado Chiapas, the family gathers around the grave, a primary internment made of a dirt mound with a cross at the head.

The purpose of this type of grave not covered by a tombstone, is that family members will eat and drink while leaving morsels of foodstuff on the mound, sprinkling it with alcoholic or other beverages to percolate into the grave. What is shared during such rituals, is referred as the “spirit” of food and drink, shared with the deceased, while thanking the departed for the lives of the living.

Need be understood here that “spirit” does not refer to the products. Those are only bearers of the intense emotional commitment of the participants to the ceremony. The flowered cross in the background is used to “talk” with the departed.

Need be understood here that “spirit” does not refer to the products. Those are only bearers of the intense emotional commitment of the participants to the ceremony. The flowered cross in the background is used to “talk” with the departed.

At that time are introduced new born children to the family, the descendants and tangible continuity in the family chain of life. Small toys may then be left on the mound for departed small children, or hand tools adults used during their lifetime, bearers of sadness.

Each province in Mexico, and other parts of the Americas, have their own traditions and rituals to commemorate the Day of the Dead, that vary between regions and locations. The common denominator however, is the respect and affection owed the ancestors, since the belief is deeply grounded in the simple motto: No ancestors>No descendant>No Life.

Ancestor veneration is not a substitute to established religion, regardless of creed. The fundamental difference between the role of religion and that of ancestor veneration however, is that the first is collective, while the second is strictly personal. In other words, ancestor worship is tangible because it rests on the living that acknowledge their family ascendants, and no one else. While a creed answers the spiritual needs of a culturally homogenous community.

Ancestor veneration does not exclude religious worship as a collective participation. The perceived antagonism by the conquerors of the New World led to brutal repression and ensuing fragmentation of ancestral belief structures. The venerated ancestors, in the past buried under the floor of the household or in its immediate vicinity, were relegated to the outskirts of the village. The concept of cemetery was then unknown by pre-European contact cultures.

Ancestor veneration does not exclude religious worship as a collective participation. The perceived antagonism by the conquerors of the New World led to brutal repression and ensuing fragmentation of ancestral belief structures. The venerated ancestors, in the past buried under the floor of the household or in its immediate vicinity, were relegated to the outskirts of the village. The concept of cemetery was then unknown by pre-European contact cultures.

Organized creeds, span space and time, and are found in all parts of the world.

It is the keystone to building stable communities, since it answers people’s affective state of awareness, a condition that challenges willful consciousness.

It excludes ancestor worship however, since it was seen, in a not so distant past, as an individual’s escape from religion and its potential, socio-cultural fragmentation.

Together with a secular or civil structure, religion has been essential to human communal growth and development. Within a community and its religious structure, ancestor worship can still have a place, there is no antagonism, since rituals are not mutually exclusive. After all, is not the theme of the persistence of life, central to both?

The Day of the Dead is about the joyful celebration of Life, and may then be called: The Day of the Ancestors.

If You Go:

The 8 Best Places to Celebrate the Day of the Dead in Mexico

About the author:

Freelance writer, researcher, and photographer, Georges Fery (georgefery.com) addresses topics, from history, culture, and beliefs to daily living of ancient and today’s indigenous communities of the Americas. His articles are published online in the U.S. at travelthruhistory.com, popular-archaeology.com, and ancient-origins.net, as well as in the quarterly magazine Ancient American (ancientamerican.com). In the U.K. his articles are found in mexicolore.co.uk.

The author is a fellow of the Institute of Maya Studies instituteofmayastudies.org Miami, FL, and The Royal Geographical Society, London, U.K. rgs.org. As well as a member in good standing of the Maya Exploration Center, Austin, TX mayaexploration.org, the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston, MA archaeological.org, NFAA-Non Fiction Authors Association nonfictionauthrosassociation.com, and the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. americanindian.si.edu.

Arriving in Quiahuiztlan (pronounced “key-ah-wheez-tlahn”) you may feel that you are in Machu Picchu as this site is situated on a terraced slope adjoining a jagged mountain named Peñon de Bernal. With the aid of defensive walls, the residents must have felt relatively safe from any threats from below. These walls had proven to be ineffective as this city had also been subjugated by the Aztecs; now the Spanish were climbing the steep hill to make first contact.

Arriving in Quiahuiztlan (pronounced “key-ah-wheez-tlahn”) you may feel that you are in Machu Picchu as this site is situated on a terraced slope adjoining a jagged mountain named Peñon de Bernal. With the aid of defensive walls, the residents must have felt relatively safe from any threats from below. These walls had proven to be ineffective as this city had also been subjugated by the Aztecs; now the Spanish were climbing the steep hill to make first contact.

Walk towards the river and you find the massively large and gnarled tree known as the Ceiba de la Noche Feliz. One root running along the ground is over 65 feet long and at least 3 feet in diameter. Cortés and his men were said to tie their boats to this tree. When you see how far this tree is from the river, they either used very long ropes or the river has since changed its course and moved further away.

Walk towards the river and you find the massively large and gnarled tree known as the Ceiba de la Noche Feliz. One root running along the ground is over 65 feet long and at least 3 feet in diameter. Cortés and his men were said to tie their boats to this tree. When you see how far this tree is from the river, they either used very long ropes or the river has since changed its course and moved further away.

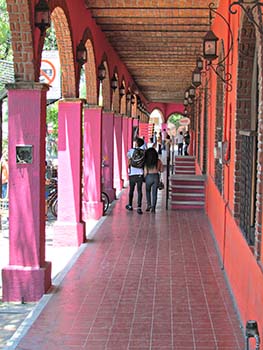

While in Ajijic I visited Tlaquepacque. I thought it would be “touristy” but I was wrong. The scores of local people experiencing the magic Tlaquepacque offers, put that myth to rest.

While in Ajijic I visited Tlaquepacque. I thought it would be “touristy” but I was wrong. The scores of local people experiencing the magic Tlaquepacque offers, put that myth to rest.

The Jardin Hidalgo filled with laughter, music, chirping birds, and happy people is the heart of Tlaquepacque. Its melodious fountains, numerous flower beds and shady trees, provides a visually stunning space for those seeking to get away from the crowded avenues. The colorful bandstand draws those who are seeking shade on a sizzling sunny day. Surrounded by Tlaquepacque’s two churches, you are sure to hear the ringing of church bells. Take time to walk around the square, you will not be disappointed.

The Jardin Hidalgo filled with laughter, music, chirping birds, and happy people is the heart of Tlaquepacque. Its melodious fountains, numerous flower beds and shady trees, provides a visually stunning space for those seeking to get away from the crowded avenues. The colorful bandstand draws those who are seeking shade on a sizzling sunny day. Surrounded by Tlaquepacque’s two churches, you are sure to hear the ringing of church bells. Take time to walk around the square, you will not be disappointed. While there are many shops to tempt you with handmade items, interesting items for sale can be found if you just look down. While walking in front of the Santuario de Nuestra Senora de la Soledad Church (behind the Jardin Hildalgo), I spotted this artisan creating crucifixes out of palm fronds. Her hands were magical. I was captivated by the speed with which she fashioned a frond into a crucifix. There are many artisans like this scattered around town, just keep your eyes open and you are bound to find a special souvenir.

While there are many shops to tempt you with handmade items, interesting items for sale can be found if you just look down. While walking in front of the Santuario de Nuestra Senora de la Soledad Church (behind the Jardin Hildalgo), I spotted this artisan creating crucifixes out of palm fronds. Her hands were magical. I was captivated by the speed with which she fashioned a frond into a crucifix. There are many artisans like this scattered around town, just keep your eyes open and you are bound to find a special souvenir. Amazing sculptures are scattered throughout Tlaquepacque. They run the gamut from life like to surreal. What they have in common is detail, exquisite detail. My favorite is by Sergio Bustamante. Born in Mexico, he is an artist who has worked in all mediums but is best known for his sculptures. As I stood in front of this sculpture, a gentleman shared that Bustamante was fascinated by the thought of children flying and often had dreams of flying as a child. This sculpture, according to him, was based on that theme.

Amazing sculptures are scattered throughout Tlaquepacque. They run the gamut from life like to surreal. What they have in common is detail, exquisite detail. My favorite is by Sergio Bustamante. Born in Mexico, he is an artist who has worked in all mediums but is best known for his sculptures. As I stood in front of this sculpture, a gentleman shared that Bustamante was fascinated by the thought of children flying and often had dreams of flying as a child. This sculpture, according to him, was based on that theme. Bustamante has a gallery on Calle Independencia. I walked inside hoping to find out more about the flying theme. It was a weekend and they were busy. The next visit will be mid week…I am planning on having my questions answered.

Bustamante has a gallery on Calle Independencia. I walked inside hoping to find out more about the flying theme. It was a weekend and they were busy. The next visit will be mid week…I am planning on having my questions answered.

I was excited to investigate X’quequen (eggy-kay-gun) the Cenote at Zipnup, approximately 4 Km south west of Vallalodid.

I was excited to investigate X’quequen (eggy-kay-gun) the Cenote at Zipnup, approximately 4 Km south west of Vallalodid.