Fruits of Labor

by Sarah Humphreys

Traveling through Tuscany in autumn, you are bound to spot olive groves alive with activity as nets are spread out under the trees and olive pickers gather in La Raccolta (Harvest). This yearly event is an ancient tradition and methods have changed little over the centuries.

Preparation for the harvest takes place in spring when the trees are carefully pruned to maximize the number of olives a tree will produce. The pruned branches are then burnt in the fields.

To create the highest quality olive oil, it is vital to time the harvest perfectly. Unlike in other regions, olives in Tuscany are picked before they are ready to fall from the tree. This produces a fruity and lean extra virgin olive oil, even if the yield is lower. The ideal time to harvest is when the unripe green olives begin to mature and turn black, which is when they contain the highest quality oil. However, this is easier said than done since even olives on the same tree may mature at different rates. The flavours of green and black olives vary but both are needed to make good quality oil. The initial oil is generally more bitter but olives that fall when too ripe make poorer quality oil. Plucked directly from the tree, the fruit is extremely bitter and almost inedible.

To create the highest quality olive oil, it is vital to time the harvest perfectly. Unlike in other regions, olives in Tuscany are picked before they are ready to fall from the tree. This produces a fruity and lean extra virgin olive oil, even if the yield is lower. The ideal time to harvest is when the unripe green olives begin to mature and turn black, which is when they contain the highest quality oil. However, this is easier said than done since even olives on the same tree may mature at different rates. The flavours of green and black olives vary but both are needed to make good quality oil. The initial oil is generally more bitter but olives that fall when too ripe make poorer quality oil. Plucked directly from the tree, the fruit is extremely bitter and almost inedible.

The ideal olive picking team consists of as many family members and friends as possible to share the labour. Firstly, huge nets are spread out around the trunk of a tree. Naturally, most olive groves are far from flat so the nets often have to be propped up by sticks or branches pruned from the trees to prevent the precious harvest from rolling away.

The ideal olive picking team consists of as many family members and friends as possible to share the labour. Firstly, huge nets are spread out around the trunk of a tree. Naturally, most olive groves are far from flat so the nets often have to be propped up by sticks or branches pruned from the trees to prevent the precious harvest from rolling away.

When the nets are in place, olives are removed by hand, with metal pincers or with plastic combs. Long rakes are used to reach the fruit on the higher branches. Ladders can be used to reach the tops of the trees but it is best to leave tree climbing to experienced olive-pickers since the trees can be brittle and slippery. When picking olives from lower trees, baskets or buckets are used to collect the fruit directly and nets are not always necessary.

After as many olives as possible have been plucked, they are rolled to the centre of the nets, and then “cleaned” by removing most of the leaves and any twigs or debris by hand before being transferred into sacks or crates. The equipment is then all moved to the next tree and the process is started all over again.

Although very light, the nets are rather cumbersome to move around and harvesters often have to stand in uncomfortable positions on steep slopes. It is essential to gather the harvest before the weather becomes too cold, so work needs to take place, rain or shine. It is also essential not to crush the olives that have fallen onto the nets so you need to be careful where you put your feet.

Although very light, the nets are rather cumbersome to move around and harvesters often have to stand in uncomfortable positions on steep slopes. It is essential to gather the harvest before the weather becomes too cold, so work needs to take place, rain or shine. It is also essential not to crush the olives that have fallen onto the nets so you need to be careful where you put your feet.

A mechanical “tree-shaking” device called an “oliviero” is sometimes used to remove olives from the trees but most of the hard work is still done by hand. It takes around 4 or 5 kilos of olives to make a litre of oil and an average harvester can pick around seven kilos of olives per hour by hand.

La Raccolta is a wonderful way of bringing together people of all ages and uniting them under the olive branch. Hard work is usually sustained with a hearty picnic in the fields washed down with a little vino. The delicate process from tree to bottle is painstaking and labour intensive but well worth the effort for the first taste of delicious freshly pressed “liquid gold.”

Guided Hiking Tour in Tuscany with Lunch Wine and Olive Oil Tasting

If You Go:

The main airports in Tuscany are Pisa Galileo Galilei and Florence Peretola. The main train station in Pisa is Pisa Centrale, which can be reached by bus or taxi from the airport. Florence airport has a regular bus service to Santa Maria Novella, the main train station in Florence. You may well need to hire a car if you wish to participate in olive picking.

Links to olive picking holidays:

Olive harvest experience at a Tuscan grove

Chianti olive picking

Farm Holidays La Baghera

Green Holiday Italy

About the author:

Sarah Humphreys is originally from near Liverpool, UK and has lived in Canada, The USA, The Czech Republic, Greece and Italy. She currently lives in Pistoia, near Florence, where she teaches English, writes freelance and is a part-time poet. She has been writing since she could hold a pencil and her passions include Literature, poetry, music and travel. Follow her on twitter: Sarah Humphreys @frizeytriton.

All photos by Sarah Humphreys except #4 which is by Isacco Marini:

Multi-coloured olives

Setting up the nets

Cleaning the olives

Il Frantoio – The finished product

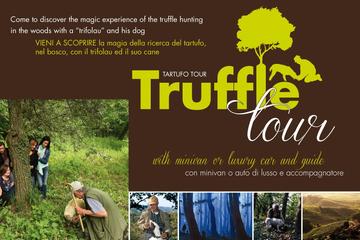

What faithfully happens, as summer turns to autumn in Tuscany, is that people come down with a pernicious fever – let’s call it ‘acute funghiosis’ – which causes a delirious devotion to truffles. Truffles are discussed with the same intensity and fervor usually reserved for Plato. They are hunted, worshipped, prized, prepared and savoured — after which, the experience of hunting, worshipping, prizing, preparing and savoring is again examined with near-religious ecstasy. This epidemic grips the palate of anyone who eats, and can be cured foremost with a generous serving of taglierini alla tartufo.

What faithfully happens, as summer turns to autumn in Tuscany, is that people come down with a pernicious fever – let’s call it ‘acute funghiosis’ – which causes a delirious devotion to truffles. Truffles are discussed with the same intensity and fervor usually reserved for Plato. They are hunted, worshipped, prized, prepared and savoured — after which, the experience of hunting, worshipping, prizing, preparing and savoring is again examined with near-religious ecstasy. This epidemic grips the palate of anyone who eats, and can be cured foremost with a generous serving of taglierini alla tartufo. Now, this is also Olive Oil season, with capital ‘O’ s , and everywhere you go is the promise of 42 extra-virgins in heaven. Hand picked, hand pressed, home bottled, first run, double extra, organic, small batch, cottage industry silken oil flows more vigorously and greener than the Arno. Beautiful handblown bottles with delicately drawn artisanal labels beckon you from shop windows and market stalls with their liquid treasure of early fresh earthen green oil. Sadly, by the time it hits our shores, its colour and flavour have mellowed and that newborn nutty taste is but a memory of the motherland.

Now, this is also Olive Oil season, with capital ‘O’ s , and everywhere you go is the promise of 42 extra-virgins in heaven. Hand picked, hand pressed, home bottled, first run, double extra, organic, small batch, cottage industry silken oil flows more vigorously and greener than the Arno. Beautiful handblown bottles with delicately drawn artisanal labels beckon you from shop windows and market stalls with their liquid treasure of early fresh earthen green oil. Sadly, by the time it hits our shores, its colour and flavour have mellowed and that newborn nutty taste is but a memory of the motherland. The next day, with late October sun on the city’s shoulders, I headed by local bus to the nearby borough of Fiesole, perched high in the emerald hills overlooking Florence. There is a spectacular hotel here, The Villa San Michele, of the Orient-Express group, that delivers luxurious vistas of the Florentine valley while dining al fresco. Skipping an overnight stay, I opted for the ‘express’ route of lunching like a local.

The next day, with late October sun on the city’s shoulders, I headed by local bus to the nearby borough of Fiesole, perched high in the emerald hills overlooking Florence. There is a spectacular hotel here, The Villa San Michele, of the Orient-Express group, that delivers luxurious vistas of the Florentine valley while dining al fresco. Skipping an overnight stay, I opted for the ‘express’ route of lunching like a local.

Cistercian monks built the round chapel of Montesiepi around the “cross” in the stone. The domed roof is built of concentric circles of alternating white stone and terracotta and frescos by Sienese painter Ambrogio Lorenzetti decorate the walls. It has been claimed that the chapel itself is a “book in stone” hiding the location of The Holy Grail.

Cistercian monks built the round chapel of Montesiepi around the “cross” in the stone. The domed roof is built of concentric circles of alternating white stone and terracotta and frescos by Sienese painter Ambrogio Lorenzetti decorate the walls. It has been claimed that the chapel itself is a “book in stone” hiding the location of The Holy Grail.

Italian scholars claim that Galgano’s Sword in The Stone precedes Arthurian legends and the original story may well be Italian. The first stories of King Arthur appear decades after Galgano’s canonization, in a poem by Burgundian poet Robert de Bron. It has been suggested tales of The Round Table may have been inspired by the round chapel and the name Galgano was altered to become Gawain. Claims that the Italian sword was a fake, made to echo Celtic legends of King Arthur, have been recently disproved. The skeletal arms in the chapel have been carbon-dated to the 12th Century, and metal dating research in 2001, by the University of Siena, indicates the Italian sword has medieval origins. Could it be that the stories of King Arthur are really based on Italian history?

Italian scholars claim that Galgano’s Sword in The Stone precedes Arthurian legends and the original story may well be Italian. The first stories of King Arthur appear decades after Galgano’s canonization, in a poem by Burgundian poet Robert de Bron. It has been suggested tales of The Round Table may have been inspired by the round chapel and the name Galgano was altered to become Gawain. Claims that the Italian sword was a fake, made to echo Celtic legends of King Arthur, have been recently disproved. The skeletal arms in the chapel have been carbon-dated to the 12th Century, and metal dating research in 2001, by the University of Siena, indicates the Italian sword has medieval origins. Could it be that the stories of King Arthur are really based on Italian history? Every summer the company Opera Festival Firenze holds classical music concerts and operas in this splendid setting. Performed annually, a spine-tingling rendition of “Carmina Burana “ under the Tuscan stars, is unforgettable. Other favourites include Vivaldi’s ”Four Seasons, “Swan Lake” and “La Traviata.”

Every summer the company Opera Festival Firenze holds classical music concerts and operas in this splendid setting. Performed annually, a spine-tingling rendition of “Carmina Burana “ under the Tuscan stars, is unforgettable. Other favourites include Vivaldi’s ”Four Seasons, “Swan Lake” and “La Traviata.”

The first written records of this Estrucan village are from 929 AD. Named for the former Bishop of Modena in the 10th century San Gimignano is a Unesco World Heritage site and is also known as the city of beautiful towers. During The Middle Ages while at the peak of it’s influence this town boasted fifty-six towers, some standing more then fifty meters tall and visible from anywhere in the Elsa Valley. These towers were not only status symbols to local families as well they served as a medieval early warning system should would be invaders approach. Because of war, the Black Plague in the 14th century, urban renewal and other catastrophes only fourteen of the towers remain and only one, The Grossa tower was open for our viewing.

The first written records of this Estrucan village are from 929 AD. Named for the former Bishop of Modena in the 10th century San Gimignano is a Unesco World Heritage site and is also known as the city of beautiful towers. During The Middle Ages while at the peak of it’s influence this town boasted fifty-six towers, some standing more then fifty meters tall and visible from anywhere in the Elsa Valley. These towers were not only status symbols to local families as well they served as a medieval early warning system should would be invaders approach. Because of war, the Black Plague in the 14th century, urban renewal and other catastrophes only fourteen of the towers remain and only one, The Grossa tower was open for our viewing.

Being surrounded by so much history can be a little over whelming so we took a time out to clear our heads and check out the terra cotta and glazed pottery. Crafts and pottery that have been produced by local artisans are abundant in the open-air market and shops along Via Giovanni. I couldn’t resist bringing a handcrafted ornament home for my grand daughter.

Being surrounded by so much history can be a little over whelming so we took a time out to clear our heads and check out the terra cotta and glazed pottery. Crafts and pottery that have been produced by local artisans are abundant in the open-air market and shops along Via Giovanni. I couldn’t resist bringing a handcrafted ornament home for my grand daughter. Fattorio Lischeto boasts a restored rustic farmhouse where we enjoyed the best of Tuscan cuisine and the company of fellow travelers from around the globe. The panoramic views of the surrounding farmland, Cypress groves, rolling hills and valleys could only surpassed the crispy crostini and pancheta, organic pecorino cheese, panchino tomatoes freshly picked from the garden and a drizzle of virgin olive oil. I still smile when I think of the organic Chianti.

Fattorio Lischeto boasts a restored rustic farmhouse where we enjoyed the best of Tuscan cuisine and the company of fellow travelers from around the globe. The panoramic views of the surrounding farmland, Cypress groves, rolling hills and valleys could only surpassed the crispy crostini and pancheta, organic pecorino cheese, panchino tomatoes freshly picked from the garden and a drizzle of virgin olive oil. I still smile when I think of the organic Chianti. While San Gimignano is a busy tourist destination Volterra is what I had envisioned when I thought about an ancient Estrucan town. The City of Alabaster as it is known became important in the 18th century in part because of the quality and transparency of the alabaster in the region. To this day craftsman work in the dust filled workshops where you can watch them work and spend whatever amount you desire large or small for your memories. In celebration of their history of carving Volterra’s Museum of Alabaster boasts over three hundred original pieces, displayed in a 17th century convent.

While San Gimignano is a busy tourist destination Volterra is what I had envisioned when I thought about an ancient Estrucan town. The City of Alabaster as it is known became important in the 18th century in part because of the quality and transparency of the alabaster in the region. To this day craftsman work in the dust filled workshops where you can watch them work and spend whatever amount you desire large or small for your memories. In celebration of their history of carving Volterra’s Museum of Alabaster boasts over three hundred original pieces, displayed in a 17th century convent. Early Roman influence is apparent in Volterra with the recent (in Tuscan time) discovery of the ruins of the Theatre of Vallebona from the 1st century and spa buildings from the Augustun age (5th century). Many of the archaeological finds from digs in and around Volterra and the Elsa Valley are displayed in the Guarnacci Museum, one of the first public museums in Europe that was founded in 1761 while the Romanesque style church of St. Agostino is the home to remnants of famous frescoes.

Early Roman influence is apparent in Volterra with the recent (in Tuscan time) discovery of the ruins of the Theatre of Vallebona from the 1st century and spa buildings from the Augustun age (5th century). Many of the archaeological finds from digs in and around Volterra and the Elsa Valley are displayed in the Guarnacci Museum, one of the first public museums in Europe that was founded in 1761 while the Romanesque style church of St. Agostino is the home to remnants of famous frescoes.