by Elisabeth Herschbach

To the casual passerby, it doesn’t look like anything out of the ordinary: just a simple, wooden house on a quiet, tree-lined street in Middletown, Rhode Island. But from 1729 to 1731, the house at 311 Berkeley Avenue — a sturdy, rust-red farmhouse, two stories high — was the residence of one of the most prominent philosophers of the 18th century, the great Irish philosopher and Anglican clergyman George Berkeley.

Whitehall, as Berkeley called his Rhode Island home, was built from an existing structure on a plot of farmland a few miles from Newport. Berkeley himself oversaw the design, incorporating architectural details uncommon in New England at the time, including a hipped roof and double front door in Palladian style. After Berkeley’s departure, Whitehall underwent various transformations, from tavern to teahouse to family farmstead. During the American Revolution, British officers headquartered in the house; by the 1890s, Whitehall was being used as a storage facility for hay, fast falling into disrepair until rescued by three historically minded Newport women. Since 1900, Whitehall has been maintained by the National Society of the Colonial Dames, whose members renovated the house, furnished it in 18th century style, and opened it as a museum dedicated to preserving Berkeley’s legacy.

If a tree falls in Middletown, and nobody is there to hear it…

Born in 1685 in southeast Ireland and educated at Trinity College, Dublin, Berkeley was a wide-ranging thinker who wrote not only on philosophy, but also on mathematics, optics, economics, and even medicine. (During his own day, the most popular of Berkeley’s works was a tract extolling the medicinal virtues of tar-water.) Today, Berkeley is most famous for his view that material objects exist only as perceptions or ideas in people’s minds, a philosophical position known as “immaterialism” or “idealism.”

Counterintuitive as the view may be, it was endorsed by Berkeley as an answer to skeptical doubts about the possibility of knowledge. How do we know that the world actually resembles our ideas and perceptions of it? Worse yet, how do we know that the things we perceive really exist? (We are all familiar with hallucinations; can we be sure that all perception is not like that?) For Berkeley, the solution was to deny that matter exists independently of the mind. We can be sure that things in the world really are as they appear to us, he reasoned, only if material objects just are ideas in our minds. Hence Berkeley’s famous slogan “to be is to be perceived.”

Counterintuitive as the view may be, it was endorsed by Berkeley as an answer to skeptical doubts about the possibility of knowledge. How do we know that the world actually resembles our ideas and perceptions of it? Worse yet, how do we know that the things we perceive really exist? (We are all familiar with hallucinations; can we be sure that all perception is not like that?) For Berkeley, the solution was to deny that matter exists independently of the mind. We can be sure that things in the world really are as they appear to us, he reasoned, only if material objects just are ideas in our minds. Hence Berkeley’s famous slogan “to be is to be perceived.”

So, to put a twist on the old riddle about the tree in the forest, if a tree falls and nobody is around to perceive it, does Berkeley’s view entail that the tree itself doesn’t exist? Fortunately, Berkeley had an explanation for why trees don’t disappear when nobody is looking and tables and chairs don’t pop out of existence every time we blink: God’s always watching.

Off to Bermuda— via Rhode Island

By the time Berkeley set sail across the Atlantic in 1729, his reputation as a philosopher was long-established; his most important works had been written almost two decades earlier when he was in his 20s. What brought Berkeley to Rhode Island was not his philosophical theory of idealism, but idealism in the ordinary sense. Berkeley was on his way to Bermuda, where he hoped to found a college for English colonists and American Indians that would be “a fountain or reservoir of learning and religion” in the New World, as he explained in a proposal published in 1725. His proposal won the approval of King George I, and Berkeley was promised a grant of £20,000 to put his utopian scheme into practice.

Newly married, Berkeley arrived in Newport in January 1729, planning to use Rhode Island as a base while waiting for the promised funds to be disbursed. “I was never more agreeably surprised than at the first sight of the town and its harbour,” he wrote a few months later to a friend in Dublin. The topography is “pleasantly laid out in hills and vales and rising grounds,” he observed enthusiastically, and “hath plenty of excellent springs and fine rivulets, and many delightful landscapes of rocks and promontories and adjacent islands.”

Details of these “delightful landscapes” made their way into Berkeley’s Alciphron, or the Minute Philosopher, a work in philosophical theology written in dialogue form and composed during Berkeley’s residence at Whitehall. The setting for the second dialogue, for example, is a hollow between two rocks overlooking a sandy beach, thought to refer to Hanging Rock, now part of Norman Bird Sanctuary, near Sachuest Beach, Middletown. Indeed, some still call the spot “Berkeley’s Seat,” in keeping with local legend that says that Berkeley penned much of Alciphron at Hanging Rock, a favorite haunt not far from Whitehall.

During Berkeley’s time, Whitehall was situated on a 96-acre farm managed in large part by his wife, Anne, and intended as a source of provisions for the college in Bermuda. Unsurprisingly, Whitehall also became a center for lively philosophical discussions. The Redwood Library and Athenaeum in Newport, America’s oldest lending library, traces its origins to a literary and philosophical society first formed under Berkeley’s guidance.

A failed plan, but a lasting legacy

Berkeley spent almost three years in Middletown waiting for his Bermuda grant. Eventually, it became clear that the funds would not materialize, and Berkeley and his family returned to London in 1731, never having set foot in Bermuda. Unfortunately, the Berkeleys’ infant daughter, Lucia, died a few days before their departure and was buried at Trinity Church in Queen Anne Square, Newport, a church where Berkeley himself had occasionally preached. Shortly after his return, Berkeley was appointed Bishop of Cloyne, Ireland, where he served for almost 20 years, until his death in 1753.

Although Berkeley never realized his dream of establishing a “fountain of learning” in Bermuda, his sojourn in Rhode Island did succeed in advancing the cause of education in the New World. Upon his departure, Berkeley donated his library and Whitehall estate to Yale University— a contribution Yale commemorated by naming both its Divinity School and one of its 12 residential colleges after the esteemed philosopher. King’s College in New York, the precursor to Columbia University, was designed following a model recommended by Berkeley to its first president, Samuel Johnson, a frequent visitor to Whitehall. And Whitehall itself now functions not just as a museum but also as a research library stocked with scholarly literature on Berkeley and many early editions of his work.

Every summer, Berkeley’s former home opens its doors to a number of scholars selected by the International Berkeley Society to be Scholars in Residence. In addition to pursuing their own research, the resident scholars give tours to visitors who wish to explore the museum, stroll through the adjoining18th century herb garden, and celebrate the legacy of a great philosopher who, for a short time, was also a great Rhode Islander.

If You Go:

Whitehall Museum House (311 Berkeley Avenue, Middletown, RI 02842) is open to visitors for guided tours in July and August (Tuesday through Sunday, 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.) and by appointment during the rest of the year. Admission is by donation.

For information, call (401) 846-3116, or email info@whitehallmuseumhouse.org.

George Berkeley in Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

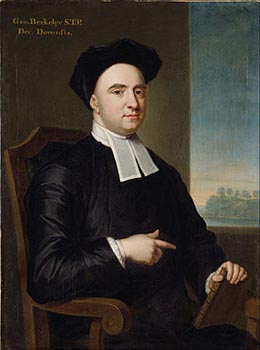

18th-century Irish philosopher George Berkeley lived at Whitehall from 1729 to 1731.

About the author:

Elisabeth Herschbach lives in Maryland with her husband and son. She works as an editor, and in her spare time she likes to travel, write, and translate. Her translation of the novel Eroica by Kosmas Politis was awarded the Constantinides Memorial Translation Prize by the Modern Greek Studies Association in 2009.

Photo credits:

Whitehall by JERRYE & ROY KLOTZ MD / CC BY-SA

George Berkeley portrait by John Smibert / Public domain

I started my day at Alaska’s oldest and smallest National Park, or as the locals call it, Totem Park, In the center of the park is a commemorative plaque to mark the battle of 1804 between Russia’s Alexander Baranov and the Kiksadi Indians. This decisive battle marked the last major Native resistance in Sitka to European domination of Alaska. A storyboard depicts this historic event. Take special note of the Russian blacksmith hammer shown, the Kiksadi first acquired the hammer as a war prize in their attack on the Russian fort at Old Sitka. The hammer is on display in the Visitor’s Center.

I started my day at Alaska’s oldest and smallest National Park, or as the locals call it, Totem Park, In the center of the park is a commemorative plaque to mark the battle of 1804 between Russia’s Alexander Baranov and the Kiksadi Indians. This decisive battle marked the last major Native resistance in Sitka to European domination of Alaska. A storyboard depicts this historic event. Take special note of the Russian blacksmith hammer shown, the Kiksadi first acquired the hammer as a war prize in their attack on the Russian fort at Old Sitka. The hammer is on display in the Visitor’s Center.

Continue west on Lincoln Street and in a few yards you’ll come to a large sign that marks Castle Hill, also known as Baranof Castle. Tlingits, Russians and Americans have all claimed and occupied this site. First as a lookout point to defend the Tlingit Indian’s home, then Baranof’s Castle was the focal point of the Russian American company and housed the Russian Government and lastly the site where the transfer of Alaska to the United States took place in 1867. This by far is my favorite Russian American site not only because of the historic significance but also of the commanding 360-degree view over the town and water.

Continue west on Lincoln Street and in a few yards you’ll come to a large sign that marks Castle Hill, also known as Baranof Castle. Tlingits, Russians and Americans have all claimed and occupied this site. First as a lookout point to defend the Tlingit Indian’s home, then Baranof’s Castle was the focal point of the Russian American company and housed the Russian Government and lastly the site where the transfer of Alaska to the United States took place in 1867. This by far is my favorite Russian American site not only because of the historic significance but also of the commanding 360-degree view over the town and water.

Usually in such a place, you may only view rooms from a doorway and snap a photo, so imagine my delight to find that for the same price as the Best Western a few blocks away, you can spend the night in this piece of living history.

Usually in such a place, you may only view rooms from a doorway and snap a photo, so imagine my delight to find that for the same price as the Best Western a few blocks away, you can spend the night in this piece of living history. Mr. Bandini was known for both his huge parties, and his political involvement. Guests travelled long distances to attend his famous 3 day fandangos involving food, drinks, music and a favorite of Mr. Bandini’s, dancing. Though known as a gracious host, it was not all fun and games for Juan Bandini. Many important political meetings that shaped the history of California were held right here in the salon. Here, along with other prominent Californios, Bandini planned revolts against more than one Mexican ruler of the day. During the Mexican-American war Juan Bandini was an American supporter and this home was the headquarters for Commodore Stockton. It was here that scout Kit Carson was sent by General Kearny to request aid in the battle of San Pasqual.

Mr. Bandini was known for both his huge parties, and his political involvement. Guests travelled long distances to attend his famous 3 day fandangos involving food, drinks, music and a favorite of Mr. Bandini’s, dancing. Though known as a gracious host, it was not all fun and games for Juan Bandini. Many important political meetings that shaped the history of California were held right here in the salon. Here, along with other prominent Californios, Bandini planned revolts against more than one Mexican ruler of the day. During the Mexican-American war Juan Bandini was an American supporter and this home was the headquarters for Commodore Stockton. It was here that scout Kit Carson was sent by General Kearny to request aid in the battle of San Pasqual.

Heading upstairs and walking along the expansive 2nd story veranda overlooking San Diego’s old town, it’s easy to daydream about what life might have been like in the hotels’ heyday. Close your eyes as the dry dust rises in small clouds from the dirt streets below. Listen for the clatter of the horses pulling the stagecoach up in front of the hotel to unload passengers, weary from the 35 hour passage from Los Angeles. Imagine the laughter of the saloon crowd, the bustle of the town, and the rustle of crinolines as women pass on their way to the haberdashery.

Heading upstairs and walking along the expansive 2nd story veranda overlooking San Diego’s old town, it’s easy to daydream about what life might have been like in the hotels’ heyday. Close your eyes as the dry dust rises in small clouds from the dirt streets below. Listen for the clatter of the horses pulling the stagecoach up in front of the hotel to unload passengers, weary from the 35 hour passage from Los Angeles. Imagine the laughter of the saloon crowd, the bustle of the town, and the rustle of crinolines as women pass on their way to the haberdashery. Opening the faux finished door from the veranda reveals a room filled with period furnishings. A globe shaped lamp, fashioned after the old kerosene style, sits on the table beside the dark, ornately carved bed. Wallpaper, in vintage patterns of leaves and vines form a backdrop for the thick red velvet curtains trimmed with large gold tassels. Double hung, wood framed windows on either side of the door look out onto the veranda and the town below. Each room has its own characters and features, like fireplaces or sitting rooms, though you will not find a TV in the room to distract from the authenticity of the place. The comfy cotton quilt seems like a perfect place to curl up with a book.

Opening the faux finished door from the veranda reveals a room filled with period furnishings. A globe shaped lamp, fashioned after the old kerosene style, sits on the table beside the dark, ornately carved bed. Wallpaper, in vintage patterns of leaves and vines form a backdrop for the thick red velvet curtains trimmed with large gold tassels. Double hung, wood framed windows on either side of the door look out onto the veranda and the town below. Each room has its own characters and features, like fireplaces or sitting rooms, though you will not find a TV in the room to distract from the authenticity of the place. The comfy cotton quilt seems like a perfect place to curl up with a book. When Seeley built his grand stagecoach hotel with 20 guestrooms in 1869, it may surprise you to learn that it did not include indoor plumbing. Chamber pots and outhouses were the facilities of the day. Indoor plumbing was not added until 1930. Don’t worry though, although the 2010 restoration, overseen by teams of experts and historians, included the use of as much of the original materials as possible, the bathrooms are not original. The 20 rooms were converted into 10 unique guestrooms, accommodating guest bathrooms that include pull chain toilets, pedestal sinks, modern rain head showers and in some cases antique copper or wooden soaker tubs. It still has that 1880s feeling but with all the modern conveniences.

When Seeley built his grand stagecoach hotel with 20 guestrooms in 1869, it may surprise you to learn that it did not include indoor plumbing. Chamber pots and outhouses were the facilities of the day. Indoor plumbing was not added until 1930. Don’t worry though, although the 2010 restoration, overseen by teams of experts and historians, included the use of as much of the original materials as possible, the bathrooms are not original. The 20 rooms were converted into 10 unique guestrooms, accommodating guest bathrooms that include pull chain toilets, pedestal sinks, modern rain head showers and in some cases antique copper or wooden soaker tubs. It still has that 1880s feeling but with all the modern conveniences. Leaving the hotel to explore, you are just steps from museums, interpretative displays artisans, shops, restaurants, and a theater. When night falls and the park closes, you are left with unique access to Old Town, to quietly contemplate what it was like for those early settlers of the Wild West.

Leaving the hotel to explore, you are just steps from museums, interpretative displays artisans, shops, restaurants, and a theater. When night falls and the park closes, you are left with unique access to Old Town, to quietly contemplate what it was like for those early settlers of the Wild West.

I wound my way through the ruins on a trail which took me backward in time. Pueblo Grande began as a small settlement around AD 450 and grew to over fifteen hundred people. The mound village was one of the largest Hohokam settlements in the area. At one time there were over fifty mound villages in the Salt River Valley. They got their names from the platform mounds at their centre. The mounds were urban centres with large open plazas where ceremonies were likely performed and were built with trash or soil and then capped with caliche, a lime-rich soil found in the desert which makes a good plaster when mixed with water. Pueblo Grande also included residential “suburbs”, astronomical observation facilities, waste disposal facilities, and ball courts.

I wound my way through the ruins on a trail which took me backward in time. Pueblo Grande began as a small settlement around AD 450 and grew to over fifteen hundred people. The mound village was one of the largest Hohokam settlements in the area. At one time there were over fifty mound villages in the Salt River Valley. They got their names from the platform mounds at their centre. The mounds were urban centres with large open plazas where ceremonies were likely performed and were built with trash or soil and then capped with caliche, a lime-rich soil found in the desert which makes a good plaster when mixed with water. Pueblo Grande also included residential “suburbs”, astronomical observation facilities, waste disposal facilities, and ball courts. I walked past the remains of the platform mound, the ball court, special purpose rooms, and the Solstice Room. At summer solstice sunrise and winter solstice sunset, the sun’s rays passed through the corner door and onto another door in the middle of the south wall of the Solstice Room. Some researchers think the room may have been used as a calendar.

I walked past the remains of the platform mound, the ball court, special purpose rooms, and the Solstice Room. At summer solstice sunrise and winter solstice sunset, the sun’s rays passed through the corner door and onto another door in the middle of the south wall of the Solstice Room. Some researchers think the room may have been used as a calendar.

Pueblo Grande was built at the headwaters of a major canal system. The Hohokam cultivated many plant species, including maize, cotton, squash, amaranth, little barley, and beans. Unlike today, The Salt River ran year round during Hohokam days. But the arid desert environment did not produce enough rainfall to grow crops. The Hohokam built over one thousand miles of canals and engineered the largest and most sophisticated irrigation system in the Americas, no small feat considering the primitive tools they had.

Pueblo Grande was built at the headwaters of a major canal system. The Hohokam cultivated many plant species, including maize, cotton, squash, amaranth, little barley, and beans. Unlike today, The Salt River ran year round during Hohokam days. But the arid desert environment did not produce enough rainfall to grow crops. The Hohokam built over one thousand miles of canals and engineered the largest and most sophisticated irrigation system in the Americas, no small feat considering the primitive tools they had. Mesa Grande Cultural Park contains the ruins of a temple mound built by the Hohokam between AD 1100 and AD 1400. At first glance, I was not impressed with the site. Just a mound of dirt and a ditch. The site became more interesting as I walked through it and viewed it in context of the historical information provided on sign posts. The Park of the Canals contains no mound village but displays the remains of over four thousand feet of Hohokam canals in three different sections. Also located with the Park is the Brinton Desert Botanical Garden, a small garden containing plants found within the desert environment.

Mesa Grande Cultural Park contains the ruins of a temple mound built by the Hohokam between AD 1100 and AD 1400. At first glance, I was not impressed with the site. Just a mound of dirt and a ditch. The site became more interesting as I walked through it and viewed it in context of the historical information provided on sign posts. The Park of the Canals contains no mound village but displays the remains of over four thousand feet of Hohokam canals in three different sections. Also located with the Park is the Brinton Desert Botanical Garden, a small garden containing plants found within the desert environment.

Canals remain important to irrigation within the greater Phoenix area today with nine major canals and over nine hundred miles of “laterals”, ditches taking water from the canals to delivery points. Paths alongside the waterways are used for walking, running and biking. Scottsdale, one of the other cities in the greater Phoenix area, has turned a canal area into a modern meeting place and tourist draw. The banks of Scottsdale Waterfront, in a revitalized area of downtown Scottsdale, are lined with palm trees, public art, courtyards, fountains, and walking paths. The area contains restaurants, outdoor cafés, specialty shops, and high-rise residential buildings, and hosts music and art festivals. It feels worlds away from its ancient Hohokam roots.

Canals remain important to irrigation within the greater Phoenix area today with nine major canals and over nine hundred miles of “laterals”, ditches taking water from the canals to delivery points. Paths alongside the waterways are used for walking, running and biking. Scottsdale, one of the other cities in the greater Phoenix area, has turned a canal area into a modern meeting place and tourist draw. The banks of Scottsdale Waterfront, in a revitalized area of downtown Scottsdale, are lined with palm trees, public art, courtyards, fountains, and walking paths. The area contains restaurants, outdoor cafés, specialty shops, and high-rise residential buildings, and hosts music and art festivals. It feels worlds away from its ancient Hohokam roots.