by Sarah Humphreys

“Fair Verona” is brimming with historical and artistic treasures, such as the magnificent Arena, whose sands where once stained with the blood of gladiators, but now hosts one of the most spectacular opera festivals in the world.

“Fair Verona” is brimming with historical and artistic treasures, such as the magnificent Arena, whose sands where once stained with the blood of gladiators, but now hosts one of the most spectacular opera festivals in the world.

However, it is the home of a fictional character which attracts the largest number of visitors. Each year, thousands of romantics head for “Casa di Giulietta”, (“Juliet’s House”), a 13th century building which has been claimed as the probable home of the young girl who inspired the greatest love story of all time. The Cappello family, whose crest can be seen on the wall of the house, are thought to have been the modal for Shakespeare’s Capulets. In 1905 the city of Verona bought the house from the Cappello family and visitors began to arrive.

The tunnel-like entrance to the courtyard is covered in graffiti and lovers traditionally leave their names, snippets of poetry or messages of love on panels that cover the walls, if they can find space, creating a fascinating collage dedicated to love.

The tunnel-like entrance to the courtyard is covered in graffiti and lovers traditionally leave their names, snippets of poetry or messages of love on panels that cover the walls, if they can find space, creating a fascinating collage dedicated to love.

The pretty little courtyard is usually crammed with tourists, most of whom are waiting to have their photo taken with the bronze statue of Juliet. Legend states that you will have luck in love if you touch Juliet’s right breast, and the bronze is noticeably worn from the caresses of hopefuls.

The most famous balcony in the world was actually created from pieces of a medieval sarcophagus and added to the original building in 1936. A plaque under the window is inscribed with Shakespeare’s immortal lines,

But soft, what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the East and Juliet is the sun…..

……It is my lady; O, it is my love!”

Behind the statue, the railings are covered in padlocks forming a chain created by lovers from all around the world. Couples write their names on padlocks, which can be bought from the handy gift shop, or bring their own, to write their names on and bind their love forever. This gimmick, which the cynical criticize as being solely a source of commercial profit, nevertheless creates a unique piece of living art, which is constantly changing. According to popular belief couples who leave messages on Juliet’s Wall, in any shape or form, will find eternal love.

Behind the statue, the railings are covered in padlocks forming a chain created by lovers from all around the world. Couples write their names on padlocks, which can be bought from the handy gift shop, or bring their own, to write their names on and bind their love forever. This gimmick, which the cynical criticize as being solely a source of commercial profit, nevertheless creates a unique piece of living art, which is constantly changing. According to popular belief couples who leave messages on Juliet’s Wall, in any shape or form, will find eternal love.

The idea of the padlocks was conjured up to discourage romantics from leaving messages and initials on pieces of chewing gum stuck to the walls surrounding the statue. You can still see some of the remnants, plus post-it notes with messages asking for Juliet’s intervention or help in finding a suitable match. However, those who attempt to leave such messages will be awarded a hefty fine if caught.

For a fee, it is possible to visit Juliet’s house and be a would-be Juliet on the famous balcony for a fleeting moment. Inside you can see some Renaissance frescos and the bed used in Zeffirelli’s 1968 film “Romeo and Juliet”.

Every year, Juliet receives over 5,000 letters, many simply addressed to “Juliet’s House, Verona”. Most of these letters are sent by American teenagers. Every missive is read and replied to by volunteers from “Juliet’s Club”, which is financed by the City of Verona.

As for Romeo, number 4, Via Arche Scaligere, just a few streets away, has been designated as his house. The building is private but a plaque on the wall indicates Romeo’s residence. The monastery of San Francesco al Corso is considered to be the location of the final events in the tragedy of the “star-cross’d lovers”. Soon after Shakespeare wrote “Romeo and Juliet”, a real sarcophagus was placed in the courtyard of San Francesco, which was the only monastery outside the walls of Verona, and therefore the only plausible setting for the death of the young couple. At some point in the 13th century, the lid of the sarcophagus and its contents, were taken to a secret location, and have been lost to history. Marie-Louise of Austria, Napoleon’s wife, visited the tomb and had jewellery made from fragments of the empty sarcophagus.

Although Juliet and her Romeo may never have existed, the places associated with Shakespeare’s tragic heroine have become a memorial to romantic love, a testimony to the hopes and dreams of those looking for love and a symbol of belief in eternal fidelity.

Private Romeo and Juliet Walking Tour of Verona

If You Go:

♦ The nearest airports are Verona airport which has flights from The UK, Venice Marco Polo airport and Milan (Linate).

♦ Trains run regularly from Venice (1 hour away), Milan (1 and a half two hours) and Bologna (50 minutes).

♦ Juliet’s House is on Via Cappello, just off Piazza delle Erbe. The courtyard is free to visit. Entrance to the house costs €5. Juliet’s Tomb is located in the monastery of San Francesco. Entrance costs €4.50.

♦ Juliet’s House can get very crowded in high season. Try to visit off-season, or go early in the day or around lunchtime.

♦ Juliet’s Club

About the author:

Sarah Humphreys is originally from near Liverpool, UK and has lived in Canada, The USA, The Czech Republic, Greece and Italy. She currently lives in Pistoia, near Florence, where she teaches English, writes freelance and is a part-time poet. She has been writing since she could hold a pencil and her passions include Literature, poetry, music and travel. Follow her on twitter: Sarah Humphreys @frizeytriton.

Photo credits:

Balcony of “Juliet’s House” in Verona by Guilhem Dulous / CC BY-SA

All other photos by Sarah Humphreys:

Juliet’s Statue

Graffiti in the Entrance

The Padlocks of Love

Then the Rock of Gibraltar, in all its glory, came into view. The Rock rises some 426 meters above the sea. As such, it’s almost a small mountain! Even though it’s a limestone rock, the Rock of Gibraltar is very green. The Rock has lots of vegetation and an abundance of wildlife. On its higher levels there is the Upper Rock Nature Reserve, which includes various migrating birds and the famed Gibraltar Barbary macaques.

Then the Rock of Gibraltar, in all its glory, came into view. The Rock rises some 426 meters above the sea. As such, it’s almost a small mountain! Even though it’s a limestone rock, the Rock of Gibraltar is very green. The Rock has lots of vegetation and an abundance of wildlife. On its higher levels there is the Upper Rock Nature Reserve, which includes various migrating birds and the famed Gibraltar Barbary macaques. When the taxi stopped, I was some 300 meters above sea level. Upon vacating the taxi, a few of the Rock’s Barbary macaques surrounded the entrance to the cave. Gibraltar is the only destination in Europe where you will find any Barbary macaques.

When the taxi stopped, I was some 300 meters above sea level. Upon vacating the taxi, a few of the Rock’s Barbary macaques surrounded the entrance to the cave. Gibraltar is the only destination in Europe where you will find any Barbary macaques. The tour continued towards the northern side of the Rock. It was there that we reached the Great Siege Tunnels which I briefly walked through. Their entrances are located at a point of the rock that overlooks Gibraltar’s airstrip close to the border.

The tour continued towards the northern side of the Rock. It was there that we reached the Great Siege Tunnels which I briefly walked through. Their entrances are located at a point of the rock that overlooks Gibraltar’s airstrip close to the border.

Yannis Ritsos was born in Monamvasia in 1909. An aristocrat by birth, renowned in Greece as an actor and director, he was one of Greece most beloved poets and is considered one of the five great Greek poets of the twentieth century. He won the Lenin Peace Prize in 1956 and was named a Golden Wreath Laureate in 1985.

Yannis Ritsos was born in Monamvasia in 1909. An aristocrat by birth, renowned in Greece as an actor and director, he was one of Greece most beloved poets and is considered one of the five great Greek poets of the twentieth century. He won the Lenin Peace Prize in 1956 and was named a Golden Wreath Laureate in 1985.

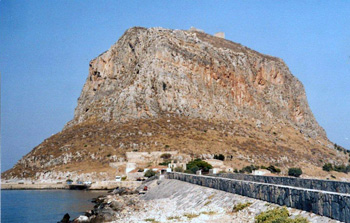

Lying on an important trade route, Monemvasia was occupied by the Venetians after pirate raids caused the inhabitants to ask for their help. There were 90 famous pirates in the Mediterranean at that time. After the Venetians took over, the town became inhabited with knights, merchants and officials. New building and restoration work began. But once Venetian power began to wane it fell to the Turks. When Turkey declared war on Venice, the city was recaptured but it wasn’t until the Greek War of Independence on July 21, 1821 that the town was liberated.

Lying on an important trade route, Monemvasia was occupied by the Venetians after pirate raids caused the inhabitants to ask for their help. There were 90 famous pirates in the Mediterranean at that time. After the Venetians took over, the town became inhabited with knights, merchants and officials. New building and restoration work began. But once Venetian power began to wane it fell to the Turks. When Turkey declared war on Venice, the city was recaptured but it wasn’t until the Greek War of Independence on July 21, 1821 that the town was liberated.

At the corner of Lysikrattis and Vironos Streets in Athens Plaka, stands a choreographic monument awarded to a choir at a Festival for Dionysos in ancient Athens’ Dionysos Theatre. Once, next to this monument, the last of its kind in Athens, was a French Capuchin convent. The poet, George, Lord Byron, stayed here when he was in Athens. At that time, the panels between the columns of the monument had been removed, so Byron used it as his study and wrote part of Childe Harold here in 1810-11. This was once the theatre district of ancient Athens, so it seemed appropriate that the flamboyant poet should choose to spend his time there. In Greek, “Vironos” means “Byron” and this is Byron’s street. I used to live there and spent much of my leisure time at the little milk shop, now a posh coffee shop, at that corner. The convent was destroyed in a fire, but there’s an inscribed monument on the spot where it once stood honouring Byron. His presence always seemed near.

At the corner of Lysikrattis and Vironos Streets in Athens Plaka, stands a choreographic monument awarded to a choir at a Festival for Dionysos in ancient Athens’ Dionysos Theatre. Once, next to this monument, the last of its kind in Athens, was a French Capuchin convent. The poet, George, Lord Byron, stayed here when he was in Athens. At that time, the panels between the columns of the monument had been removed, so Byron used it as his study and wrote part of Childe Harold here in 1810-11. This was once the theatre district of ancient Athens, so it seemed appropriate that the flamboyant poet should choose to spend his time there. In Greek, “Vironos” means “Byron” and this is Byron’s street. I used to live there and spent much of my leisure time at the little milk shop, now a posh coffee shop, at that corner. The convent was destroyed in a fire, but there’s an inscribed monument on the spot where it once stood honouring Byron. His presence always seemed near. The street adjacent, is Shelley Street, named for his poet colleague Percy Bysshe Shelly who tragically drowned in Italy. Both poets are honoured in Greece, especially Byron, who became a national hero when he joined the Greek resistance movement during the War of Independence.

The street adjacent, is Shelley Street, named for his poet colleague Percy Bysshe Shelly who tragically drowned in Italy. Both poets are honoured in Greece, especially Byron, who became a national hero when he joined the Greek resistance movement during the War of Independence. He lived for awhile on the island of Kefalonia (Cephalonia) in the tiny village of Metaxata, near Argostoli, where he enjoyed exploring the ruins of a Venetian castle at Ayios Yeoryios, once the Venetian capital of the island.

He lived for awhile on the island of Kefalonia (Cephalonia) in the tiny village of Metaxata, near Argostoli, where he enjoyed exploring the ruins of a Venetian castle at Ayios Yeoryios, once the Venetian capital of the island.