by Marc Latham

‘perhaps in every respect the most delightful in Europe… a glorious Eden.’

– Lord Byron.‘the most blessed spot on the whole inhabitable globe.’

– Robert Southey.

Looking south standing under a mountain-top cross surrounded by lush vegetation in Sintra’s Romantic-period Pena Palace park I wondered if the human construction in the distance was Lisbon. Then I saw a red bridge glinting in the sun, confirming it was Portugal’s capital city twenty-five miles away on the Tagus estuary. It could have been the Golden Gate bridge signalling San Francisco, but I was a long way from California; and the previous day I’d passed the 25 April bridge and a Rio-style Christ statue on the way to Belem, where Portuguese sailors departed on their most famous voyages of discovery.

Looking south standing under a mountain-top cross surrounded by lush vegetation in Sintra’s Romantic-period Pena Palace park I wondered if the human construction in the distance was Lisbon. Then I saw a red bridge glinting in the sun, confirming it was Portugal’s capital city twenty-five miles away on the Tagus estuary. It could have been the Golden Gate bridge signalling San Francisco, but I was a long way from California; and the previous day I’d passed the 25 April bridge and a Rio-style Christ statue on the way to Belem, where Portuguese sailors departed on their most famous voyages of discovery.

Turning around, I took a last look at the breathtakingly colourful and elaborate palace from its level. It was also visible from Sintra town, and the Sintra-Lisbon train; and is said to be visible from Belem on a clear day. Perched atop a mountain containing trees from around the world, the palace looks like a Disney castle resting in an environmentalist’s dream.

Although Sintra may have had a more natural beauty when Byron and Southey visited, it must look more impressive now; as the palace and its park were only built to their current gothic fairytale brilliance after the poets had departed. It wasn’t until 1838 that King consort (to Queen Maria II) Ferdinand II bought the land, which at the time housed a modest monastery. The royal couple employed Baron Wilhelm Ludwig von Eschwege to build the castle; to be used as a summer residence to escape the heat of Lisbon. It was completed in 1854, and became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1995.

A half-fish, half-man statue; an allegory for the creation of the world; greets visitors to the central courtyard of the Pena Palace. Entering the Manueline Cloister to view the living quarters, the sun was almost directly above a tall green plant rising out of a grey turtle-stoned pot in the centre of the unroofed inner courtyard. Upstairs, we could walk past the open bedrooms, which were surprisingly small; and through the communal rooms, which were as stylish as expected. Other highlights of the palace included the small ancient chapel, the Great Royal Hall and the kitchen; the latter now houses a cafe, with an outside terrace.

A half-fish, half-man statue; an allegory for the creation of the world; greets visitors to the central courtyard of the Pena Palace. Entering the Manueline Cloister to view the living quarters, the sun was almost directly above a tall green plant rising out of a grey turtle-stoned pot in the centre of the unroofed inner courtyard. Upstairs, we could walk past the open bedrooms, which were surprisingly small; and through the communal rooms, which were as stylish as expected. Other highlights of the palace included the small ancient chapel, the Great Royal Hall and the kitchen; the latter now houses a cafe, with an outside terrace.

It was from there that I saw the cross on the mountain’s southern peak, and decided to walk over to it. There were several paved paths through a park filled with over 2000 species of world trees and plants; from North American sequoia to New Zealand ferns. There are also several small lakes, resting places, caves and viewing points.

On the way up to the palace I had visited the Moorish Castle. It is now mostly just a long wall with towers above foundations being archaeologically excavated, but it still inspires the imagination, and provides the best views on the mountain of Sintra and the northern plain. The castle was built in the eighth and ninth centuries during the Moors’ occupation of the region, before Portuguese forces regained control in the eleventh century. You can buy tickets for both the castle and Pena Palace at the castle entrance. The castle provides a good break if walking from Sintra to the palace. There are also regular buses.

On the way up to the palace I had visited the Moorish Castle. It is now mostly just a long wall with towers above foundations being archaeologically excavated, but it still inspires the imagination, and provides the best views on the mountain of Sintra and the northern plain. The castle was built in the eighth and ninth centuries during the Moors’ occupation of the region, before Portuguese forces regained control in the eleventh century. You can buy tickets for both the castle and Pena Palace at the castle entrance. The castle provides a good break if walking from Sintra to the palace. There are also regular buses.

Lisbon’s train station for Sintra is the Rossio, which is conveniently also the city’s most central. Sintra was the only time I used the train service in Lisbon, as I travelled between Lisbon and the south coast by bus; the Eva service was comfortable and punctual, but there were no toilets or rest-stops on the three-hour journey.

Lisbon’s train station for Sintra is the Rossio, which is conveniently also the city’s most central. Sintra was the only time I used the train service in Lisbon, as I travelled between Lisbon and the south coast by bus; the Eva service was comfortable and punctual, but there were no toilets or rest-stops on the three-hour journey.

Arriving in Lisbon, its urban sprawl rising up steep hills was both impressive and daunting as the bus carried us over the Tagus on the ten-mile long Vasco da Gama; Lisbon’s other main bridge and Europe’s longest. Lisbon’s 500,000-population rises to three-million when including its outer districts. The bus dropped us off at a station on the northern edge of the city, with a large metro station underneath. I took a train to Chiado, where I’d booked two nights in a cheap hostel, after mastering the ticket machine. The machine has an English language option, and you need a day-card as well as a destination ticket.

After exiting the metro I asked a passing woman if she knew where Praca Luis de Camoes was, as that was the square on which the Royal Lisbon hostel was located. She looked at me with puzzlement in her eyes, before smiling and repeating Camoes with a ‘Camush’ pronunciation, and then said it was over the other side of the metro. So, not only did I receive directions, but I also learnt how the ‘ush’ sound I’d noticed all trip was used. It still took a little while to find the hostel, as it was in too good a position: overlooking the square rather than down a side street. Friendly staff, plush furnishings, music in the bathroom and a bumper buffet breakfast just added to the hostel’s charms.

The Chiado is a popular area of Lisbon, between the city centre; Baixa; and the Bairro Alto district. The latter’s narrow cobbled streets and balconied houses ooze age and character. Everything is in easy walking distance, with the Baixa’s plazas interconnected by picturesque streets, squares and statues. The area was rebuilt after a big earthquake in 1755. Restaurants with smartly dressed waiters and waitresses frame the plazas, continue up the eastern hill towards St. George’s Castle, and down to the Tagus a few blocks to the south.

The Chiado is a popular area of Lisbon, between the city centre; Baixa; and the Bairro Alto district. The latter’s narrow cobbled streets and balconied houses ooze age and character. Everything is in easy walking distance, with the Baixa’s plazas interconnected by picturesque streets, squares and statues. The area was rebuilt after a big earthquake in 1755. Restaurants with smartly dressed waiters and waitresses frame the plazas, continue up the eastern hill towards St. George’s Castle, and down to the Tagus a few blocks to the south.

On the day in-between arriving and going to Sintra I took a tram from near the Baixa riverside out to the western parish of Santa Maria de Belem (a translation of Saint Mary of Bethlehem). It is an area famous for its monuments and museums, and the place where Portuguese sailors departed on their greatest voyages of discovery. The Christ the King statue dominates the southern riverside’s hills, above the 25 April bridge’s high red towers. White-sailed boats passed effortlessly under the suspension bridge on an uncharacteristically cool and cloudy summer day; while parks and cycle tracks were busy with Sunday morning sportspeople.

Maybe the sailors sometimes imagine they are Henry the Navigator or Vasco da Gama as they sail out to sea. Henry was a 15th century royal who is credited with being instrumental in developing Portugal’s most rewarding era of exploration and trade. His statue looks out over the Tagus at the head of the impressive Monument to the Discoveries. Behind him are thirty-two notable figures from that era, with sixteen on each side of the caravel-shaped structure; the caravel boat revolutionised Portuguese sailing after being designed with sponsorship from Henry.

Maybe the sailors sometimes imagine they are Henry the Navigator or Vasco da Gama as they sail out to sea. Henry was a 15th century royal who is credited with being instrumental in developing Portugal’s most rewarding era of exploration and trade. His statue looks out over the Tagus at the head of the impressive Monument to the Discoveries. Behind him are thirty-two notable figures from that era, with sixteen on each side of the caravel-shaped structure; the caravel boat revolutionised Portuguese sailing after being designed with sponsorship from Henry.

Vasco da Gama is probably the most famous of the sailors on the statue. While Christopher Columbus was looking for a western passage to the East Indies for the Spanish king and instead discovering the Americas, Vasco da Gama led the first European naval expedition to reach India in 1498. The route around the south of Africa had been pioneered by another Portuguese sailor featured on the monument; Bartholomew Diaz sailed around the cape in 1488, and wanted to continue to India, but his crew refused.

The other highlight of Belem is the Belem Tower, which was built in the early sixteenth century to guard the Tagus entrance. The small fort juts out into the river, and looks straight out of a pirate film. However, it doesn’t come close to matching the Pena Palace, so if you’ve got time; and especially on a clear day; it’s worth making the short journey out to Sintra.

If You Go:

♦ Lisbon information: www.golisbon.com

♦ Pena palace and park information

♦ Royal Lisbon hostel: www.royallisbon.com/home.html

♦ Eva buses: www.eva-bus.com/novo

♦ Ryanair flights from the UK: www.ryanair.com

About the author:

Marc Latham traveled to all the populated continents during his twenties, and studied during his thirties, including a BA in History. He now lives in Leeds, and is trying to become a full-time writer from the www.greenygrey.co.uk website.

All photos are by Marc Latham.

See more at: picasaweb.google.com

by W. Ruth Kozak

by W. Ruth Kozak

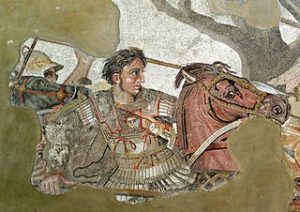

I place my hands on the magnetic lodestone of Samothraki, which represents the Great Mother. The russet-coloured stone burns beneath my touch. Supplicants used to hang iron votives here. Every member of the Macedonian royalty was initiated into the cult of the Great Mother. At one time, Alexander must have stood in this very place. Nearby I find the ruins of a small building erected in 318 BC, dedicated to Alexander and his father Philip by their sons, the join-kings, Philip Arridaios and Alexander IV.

I place my hands on the magnetic lodestone of Samothraki, which represents the Great Mother. The russet-coloured stone burns beneath my touch. Supplicants used to hang iron votives here. Every member of the Macedonian royalty was initiated into the cult of the Great Mother. At one time, Alexander must have stood in this very place. Nearby I find the ruins of a small building erected in 318 BC, dedicated to Alexander and his father Philip by their sons, the join-kings, Philip Arridaios and Alexander IV. Greek poets, tragedians, historians, philosophers, doctors, actors, painters and craftsmen were invited to the Macedonian court. One of these philosophers was Aristotle whom Philip invited to tutor his son at school he had build known as the Nymphaeion” at Mieza, near modern Naoussa. The school, called “The Peripatos” (“walk”) was a two storey L-shaped building linked by staircases, built along the face of the rock. The school’s facilities were set up to harmonize and blend in with the environment, incorporating several caves. Here, in this tranquil setting of lush vegetation, fresh water springs and caves, Aristotle taught Alexander his companions.

Greek poets, tragedians, historians, philosophers, doctors, actors, painters and craftsmen were invited to the Macedonian court. One of these philosophers was Aristotle whom Philip invited to tutor his son at school he had build known as the Nymphaeion” at Mieza, near modern Naoussa. The school, called “The Peripatos” (“walk”) was a two storey L-shaped building linked by staircases, built along the face of the rock. The school’s facilities were set up to harmonize and blend in with the environment, incorporating several caves. Here, in this tranquil setting of lush vegetation, fresh water springs and caves, Aristotle taught Alexander his companions. As I stand looking out over the ruined tiers, I try to image the scene on that fateful day. The wedding was to be a big show with carts bearing statues of the twelve gods, including one with an effigy of Philip crowned as a god. As Philip entered the theatre and dismounted from his horse, he was stabbed to death by his bodyguard. The assassin dashed out of the theatre but was overtaken and killed. Family and political intrigues were behind the murder. At the time, Alexander was estranged from his father. His mother, Olympias, a ruthless, impassioned woman, was jealous of her rivals. Soon afterwards she had Phlip’s newest wife and infant daughter murdered.

As I stand looking out over the ruined tiers, I try to image the scene on that fateful day. The wedding was to be a big show with carts bearing statues of the twelve gods, including one with an effigy of Philip crowned as a god. As Philip entered the theatre and dismounted from his horse, he was stabbed to death by his bodyguard. The assassin dashed out of the theatre but was overtaken and killed. Family and political intrigues were behind the murder. At the time, Alexander was estranged from his father. His mother, Olympias, a ruthless, impassioned woman, was jealous of her rivals. Soon afterwards she had Phlip’s newest wife and infant daughter murdered.

The city was founded by the Phoenicians, but named by the Ancient Greeks as “Panormus”, which then became “Palermo”, with the basic meaning of a place “always fit for landing in.” This aspect becomes pretty clear once to see all the people coming from Tunis and Northern Africa, for whom Palermo represents a way to make some of their dreams come true and the Tyrrhenian Sea is their only escape to a better world.

The city was founded by the Phoenicians, but named by the Ancient Greeks as “Panormus”, which then became “Palermo”, with the basic meaning of a place “always fit for landing in.” This aspect becomes pretty clear once to see all the people coming from Tunis and Northern Africa, for whom Palermo represents a way to make some of their dreams come true and the Tyrrhenian Sea is their only escape to a better world.

In Palermo, you can enjoy a refined trip, full of culture while walking on the magnificent streets in the city centre and visiting the most important treasures left by the ancestors. At the same time you can have an exotic trip, full of shocking discoveries. It all depends on which side or quarter of Palermo you choose to visit.

In Palermo, you can enjoy a refined trip, full of culture while walking on the magnificent streets in the city centre and visiting the most important treasures left by the ancestors. At the same time you can have an exotic trip, full of shocking discoveries. It all depends on which side or quarter of Palermo you choose to visit. Another place of great interest for all tourists is the Capuchin Catacombs, with many mummified corpses in varying degrees of preservation. The main attraction is a little girl, who looks as if she was really still alive.

Another place of great interest for all tourists is the Capuchin Catacombs, with many mummified corpses in varying degrees of preservation. The main attraction is a little girl, who looks as if she was really still alive. You might have heard of Palermo as being a dangerous place to go to, with stories of all the Mafia present around the streets. I’ve walked all alone or with just one other companion in Ballaro, one of the most dangerous quarters in Palermo and never encountered anything scary or frightening.

You might have heard of Palermo as being a dangerous place to go to, with stories of all the Mafia present around the streets. I’ve walked all alone or with just one other companion in Ballaro, one of the most dangerous quarters in Palermo and never encountered anything scary or frightening.

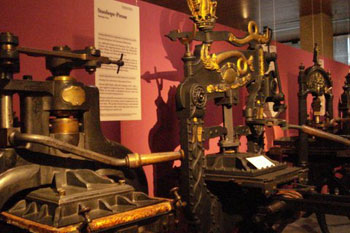

A German goldsmith, printer and publisher, Johannes Gutenberg invented the mechanical moveable type printing press and this invention started the Printing Revolution. His first major work was the Gutenberg Bible (known as the 42-line Bible). 180 of them were printed on paper and vellum, though only 21 copies survive, two of them may be seen in the museum. There is also a replica of Gutenberg’s printing press, rebuilt according to woodcuts from the 15th and 16th century.

A German goldsmith, printer and publisher, Johannes Gutenberg invented the mechanical moveable type printing press and this invention started the Printing Revolution. His first major work was the Gutenberg Bible (known as the 42-line Bible). 180 of them were printed on paper and vellum, though only 21 copies survive, two of them may be seen in the museum. There is also a replica of Gutenberg’s printing press, rebuilt according to woodcuts from the 15th and 16th century.

This museum is a must-see for anyone interested in books and printing. The Gutenberg Museum displays two copies of the Bible and Shuelburgh Bible as well as other publications representing the history of the printed word. Here you may see the very earliest typesetting machines and books that were published centuries after the Gutenberg Bible. There is also a small library open to the public that contains a collection of books from the 17th to the 20th centuries.

This museum is a must-see for anyone interested in books and printing. The Gutenberg Museum displays two copies of the Bible and Shuelburgh Bible as well as other publications representing the history of the printed word. Here you may see the very earliest typesetting machines and books that were published centuries after the Gutenberg Bible. There is also a small library open to the public that contains a collection of books from the 17th to the 20th centuries.

On March 20th, 1933, Heinrich Himmler and the temporary chief of police in Munich announced that a concentration camp had been built in small town of Dachau in Germany to imprison anyone who “opposed’ the Nazi political party.

On March 20th, 1933, Heinrich Himmler and the temporary chief of police in Munich announced that a concentration camp had been built in small town of Dachau in Germany to imprison anyone who “opposed’ the Nazi political party. The prisoners attended roll call twice a day. During this time they were forced to line up in front of the barracks and stand motionless for an hour as the camp officers would count each prisoner. If anyone had died during the night, the corpse would then be dragged to the roll call area in front of all the other prisoners to be counted. If one of the prisoners had attempted to escape during the night, all of the other inmates were forced to stand at attention for hours on end, regardless of whether the attempt was successful or not. The officers would often torture or punish the prisoner for the others to witness. Sometimes the sick and dying inmates would collapse during roll call, and if any of the fellow inmates dared to help them, they would be punished. Punishment became an hourly occurrence inside Dachau. Prisoners were punished by food withdrawal, mail bans, or at worst, the infamous pole-hanging. Inmates were forced to work throughout the entire day and well into the evening, and were only given a limited amount of time to sleep during the night. They were also forced to put on heavy winter coats while they worked outside during the summer months, or even stand naked while they worked in the cold. If a prisoner was declared “unfit for work,” they would then be transported to the Hartheim Castle, (which was about 17 kilometers away from Linz in Germany); never to be seen or heard from again.

The prisoners attended roll call twice a day. During this time they were forced to line up in front of the barracks and stand motionless for an hour as the camp officers would count each prisoner. If anyone had died during the night, the corpse would then be dragged to the roll call area in front of all the other prisoners to be counted. If one of the prisoners had attempted to escape during the night, all of the other inmates were forced to stand at attention for hours on end, regardless of whether the attempt was successful or not. The officers would often torture or punish the prisoner for the others to witness. Sometimes the sick and dying inmates would collapse during roll call, and if any of the fellow inmates dared to help them, they would be punished. Punishment became an hourly occurrence inside Dachau. Prisoners were punished by food withdrawal, mail bans, or at worst, the infamous pole-hanging. Inmates were forced to work throughout the entire day and well into the evening, and were only given a limited amount of time to sleep during the night. They were also forced to put on heavy winter coats while they worked outside during the summer months, or even stand naked while they worked in the cold. If a prisoner was declared “unfit for work,” they would then be transported to the Hartheim Castle, (which was about 17 kilometers away from Linz in Germany); never to be seen or heard from again. The barracks were used as day rooms and dormitories for the prisoners, and although each barrack was designed to hold 200 prisoners, by the end of World War II in 1945, up to 2,000 prisoners were packed into these small living quarters. (The Jewish prisoners slept in barrack #15 which was separated from the rest of the camp with barbed wire).

The barracks were used as day rooms and dormitories for the prisoners, and although each barrack was designed to hold 200 prisoners, by the end of World War II in 1945, up to 2,000 prisoners were packed into these small living quarters. (The Jewish prisoners slept in barrack #15 which was separated from the rest of the camp with barbed wire). Dachau’s crematorium was built in 1940 in order to deal with the increasing number of deaths at the camp, followed by a larger crematorium as well as a gas chamber at the end of 1942. It was inside this gas chamber where the mass murders at Dachau occurred. Fake shower sprouts were installed in the ceiling in order to fool the prisoners into thinking they were going to take a shower. Within a period of 15 to 20 minutes, approximately 150 victims would have been poisoned to death inside the gas chamber. A separate room in the crematorium area known as the “death chamber” used to store the corpses that were brought in from the camp. These corpses were then cremated in one of the stoves, and it is said that each of the stoves could cremate two to three bodies at the same time.

Dachau’s crematorium was built in 1940 in order to deal with the increasing number of deaths at the camp, followed by a larger crematorium as well as a gas chamber at the end of 1942. It was inside this gas chamber where the mass murders at Dachau occurred. Fake shower sprouts were installed in the ceiling in order to fool the prisoners into thinking they were going to take a shower. Within a period of 15 to 20 minutes, approximately 150 victims would have been poisoned to death inside the gas chamber. A separate room in the crematorium area known as the “death chamber” used to store the corpses that were brought in from the camp. These corpses were then cremated in one of the stoves, and it is said that each of the stoves could cremate two to three bodies at the same time. Unfortunately by the time American soldiers discovered Dachau on April 29th, 1945, it was already too late for many of the victims.

Unfortunately by the time American soldiers discovered Dachau on April 29th, 1945, it was already too late for many of the victims.