by Janice Porter Hayes

When my husband and I first flew into Karaganda, Kazakhstan, the first thing I noticed was the smell. The warm breezes blowing in from the vast Kazakh steppe and over the tarmac smelled almost like the air of my family’s farm, located half way around the world in the high mountain deserts of Utah.

But there the similarities ended. During our long trip, from Utah to New York, New York to Moscow, Moscow to Karaganda, the world had slowly and quietly changed. The airports became smaller and more stark, the people more foreign, the language less understood. By the time we reached Karaganda, the plane was just serviceable and when our adoption facilitator met us at the airport, we watched the steppe too disappear as we whirled toward the city itself, passing along the way, a Russian Orthodox church, a mosque, and in the distance, the dilapidated orphanage, from which we would soon adopt our new daughter.

Before our adoption journey began, I knew next to nothing about Kazakhstan, in part, because until 1991, the country had been swallowed up in that vast entity known as the Soviet Union. So swallowed, it had lost its name, its freedom, much of its language and very nearly, everything about it which made it distinctly Kazakh. Even today, driving the streets of Karaganda, one notices the crouching, well-worn blocks of Soviet style apartment buildings with their Soviet graphics and wonders at the statue of Lenin still posing in the center of town. Still, there are no statues of Stalin, and that is a comfort. After all, it was Stalin who used Karaganda; along with hundreds of other locations in the vast Asian and Siberia steppes, as a full-service slave labor camp, a part of his infamous Gulag system. For years, people were deported to Kazakhstan from places as far away as Germany, Poland, Korea and Japan, put to work in the coal mines still prevalent in the area today and kept behind fences studded with barbed wire, guard towers and patrolled by guard dogs. Alexander Solzhenitsyn; the famous Russian author and Gulag inmate, was set to work not far from Karaganda in Ekibastuz, Kazakhstan. His famous novel, “ One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”, was based on his experiences as a prisoner there.

Before our adoption journey began, I knew next to nothing about Kazakhstan, in part, because until 1991, the country had been swallowed up in that vast entity known as the Soviet Union. So swallowed, it had lost its name, its freedom, much of its language and very nearly, everything about it which made it distinctly Kazakh. Even today, driving the streets of Karaganda, one notices the crouching, well-worn blocks of Soviet style apartment buildings with their Soviet graphics and wonders at the statue of Lenin still posing in the center of town. Still, there are no statues of Stalin, and that is a comfort. After all, it was Stalin who used Karaganda; along with hundreds of other locations in the vast Asian and Siberia steppes, as a full-service slave labor camp, a part of his infamous Gulag system. For years, people were deported to Kazakhstan from places as far away as Germany, Poland, Korea and Japan, put to work in the coal mines still prevalent in the area today and kept behind fences studded with barbed wire, guard towers and patrolled by guard dogs. Alexander Solzhenitsyn; the famous Russian author and Gulag inmate, was set to work not far from Karaganda in Ekibastuz, Kazakhstan. His famous novel, “ One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”, was based on his experiences as a prisoner there.

Today, Karaganda has the feel of a city still trying to find itself. The streets are wide and often potholed, but they are kept relatively clean by an army of babushkas hunched over homemade whisk brooms. Strips of green, dotted with trees and flowers line many boulevards while the street vendors, selling everything from bananas to gladiolas, line the sidewalks. A few vendors will tell you about their allotments in the countryside where they grow the produce they sell, and a few will give you a toothless grin and hand you a bunch of apples for free. After all, Kazakh legend holds that apples were first grown in Kazakhstan.

Though economic times are tough, there is a new openness to Karaganda. We met people, from translators to drivers, to those working in the orphanages we visited, who were willing to discuss the painful past of their city, its history of Soviet oppression and to ask us in turn, about our experiences in the west. No attempt was made to hide the shoddiness of much of their surroundings nor were they too proud to ask for help, especially as it pertained to my husband and I buying much needed supplies for our daughter’s orphanage. We found the younger adults and children particularly interested in our lives, our language and why were had come so far to their city. Indeed, it was the older generation of residents who kept their distance and watched us warily when we walked past or played outside with our new daughter. Perhaps a life spent under the thumb of a communist regime had taught them to be more cautious.

Though economic times are tough, there is a new openness to Karaganda. We met people, from translators to drivers, to those working in the orphanages we visited, who were willing to discuss the painful past of their city, its history of Soviet oppression and to ask us in turn, about our experiences in the west. No attempt was made to hide the shoddiness of much of their surroundings nor were they too proud to ask for help, especially as it pertained to my husband and I buying much needed supplies for our daughter’s orphanage. We found the younger adults and children particularly interested in our lives, our language and why were had come so far to their city. Indeed, it was the older generation of residents who kept their distance and watched us warily when we walked past or played outside with our new daughter. Perhaps a life spent under the thumb of a communist regime had taught them to be more cautious.

All in all, we found Karaganda especially attractive when we were out walking, shopping and visiting among the people. The open air markets were particularly interesting, flooded with everything from exotic foods to clothing, souvenirs to other trinkets, not to mention the opportunity to watch the creative tactics used by the many beggars and street children wandering about. Foreign and familiar smells mixed, creating a potpourri loaded with the scent of flowers, apples, oregano and onion, mixed with lesser known Asian spices along with the scent of blood, animal droppings and the hunks of meat hanging in stall after stall. Most often, Russian was spoken, but Kazakh could still be heard to the discerning ear. Our adoption facilitator treated us to dinner at a Korean restaurant one night, a Georgian restaurant the next. We also managed to eat our daily lunch at a pizzeria owned by Turks. The food was plentiful, inexpensive and good.

Some of our best experiences however, focused on the spiritual rather than the temporal when we were invited to attend Sunday services in the beautiful Russian Orthodox cathedral. The religion, having been suppressed for so long under communism, seemed vibrant, the worshipers devout, the choir and ritual a balm to heart and soul. The nearby mosque was also impressive and stood as further testimony not only to Kazakhstan’s rich cultural and racial diversity, but to its new found religious freedoms as well. Trips to the surrounding countryside and out into the vast steppes were also a welcome change. Out under the endless Kazakh sky, one begins to understand this once nomadic race of people who still claim the land, air and sky as their own.

For those wishing to visit Karaganda, hotels, restaurants and apartments are available, in various price and quality ranges. While in Karaganda, my husband and I stayed in an apartment whose previous owners had emigrated to Israel, leaving the apartment, along with their clothes, family pictures and clothing, behind. Many permanent residents will move in with relatives and rent their apartments to foreigners willing to pay well and keep their apartments clean. The price for such an apartment is still reasonable and is a great way to get to know the people, places and culture of the city. Karaganda boasts a nice lake and central park in its downtown area which is a welcome change from the traffic of the streets and during the summer, a large circus plays in town which is an event the entire city looks forward to. Karaganda also supports a university and various academic institutions. There are gardens, a water park, a theater and a museum which contains many interesting displays on traditional Kazakh nomadic life which we found very well done. We also enjoyed the many monuments dotting the city, especially the massive memorial dedicated to the Kazakh effort during World War II.

For those wishing to visit Karaganda, hotels, restaurants and apartments are available, in various price and quality ranges. While in Karaganda, my husband and I stayed in an apartment whose previous owners had emigrated to Israel, leaving the apartment, along with their clothes, family pictures and clothing, behind. Many permanent residents will move in with relatives and rent their apartments to foreigners willing to pay well and keep their apartments clean. The price for such an apartment is still reasonable and is a great way to get to know the people, places and culture of the city. Karaganda boasts a nice lake and central park in its downtown area which is a welcome change from the traffic of the streets and during the summer, a large circus plays in town which is an event the entire city looks forward to. Karaganda also supports a university and various academic institutions. There are gardens, a water park, a theater and a museum which contains many interesting displays on traditional Kazakh nomadic life which we found very well done. We also enjoyed the many monuments dotting the city, especially the massive memorial dedicated to the Kazakh effort during World War II.

Perhaps an adoption will never take you to Kazakhstan, but for those travelers looking for something off the beaten path, who enjoy a rich mixture of culture, language and people, and who are willing to see into a painful past while recognizing a place struggling for a better future, Karaganda may be well worth your traveling time.

Half-Day Cossack Village Tour from Kiev

If You Go:

Web sites to access further information on Karaganda:

www.aboutkazakhstan.com

www.tripadvisor.com

www.virtualtourist.com

About the author:

Janice Porter Hayes has been a freelance writer for over 25 years, with published stories, articles and poems in many different magazines and anthologies. She has a degree in European history and work part time as a reading tutor. In her spare time she loves to read, garden, travel, take long walks with her dog, Kodiak, and spend time with family and friends. She is also involved in the community as a hospice volunteer and has served on her community library board where we started our town’s first library.

Photo Credits:

Top Karaganda photo by Ilya Varlamov under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

All other photographs by Janice Porter Hayes.

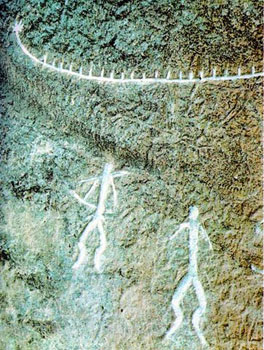

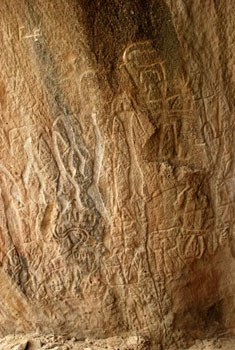

Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Gobustan contains unique rock art engravings and images depicting the lifestyle, culture, economy, world outlook, magic and totemic conception, customs and traditions of the ancient inhabitants of the area. Long time ago the sea waves licked these mountains and then abandoned them leaving characteristic relief traces on the polished rocks.

Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Gobustan contains unique rock art engravings and images depicting the lifestyle, culture, economy, world outlook, magic and totemic conception, customs and traditions of the ancient inhabitants of the area. Long time ago the sea waves licked these mountains and then abandoned them leaving characteristic relief traces on the polished rocks.

Gobustan rock carvings are marked with thematic diversity, plot originality, and certain artistic skill. Most of the petroglyphs depict people, domestic and wild animals, such as oxen, goats, gazelles, deer, horses, birds, fish, as well as battle scenes, ritual dances, bullfights, boats with men, hunting, fishing, solar symbols, etc.

Gobustan rock carvings are marked with thematic diversity, plot originality, and certain artistic skill. Most of the petroglyphs depict people, domestic and wild animals, such as oxen, goats, gazelles, deer, horses, birds, fish, as well as battle scenes, ritual dances, bullfights, boats with men, hunting, fishing, solar symbols, etc.

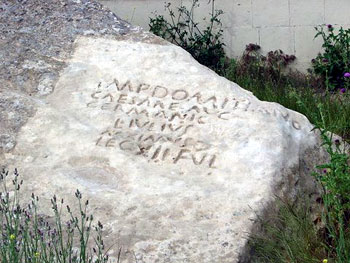

Personally, I am not sure about the presence of the Vikings in these areas. But the Romans were for sure. A rock found in Gobustan contains a Roman inscription which proves the presence of a centurion of the XII (12th) Roman legion, known as the Fulminat (Lightning) here on the shore of the Caspian Sea during the reign of Emperor Titus Flavius Domitianus in the second half the 1st century AD. Some assume, this may be the easternmost point any Roman patrol even ventured to. I can read the inscription though I am not good in Latin: “IMP DOMITIANO CAESARE AVG GERMANIC LIVIVS MAXIMVS LEG XII FVL” (“Emperor Domitian, the Blessed Caesar Germanicus. Livius Maximus, Legio XII Fulminata”).

Personally, I am not sure about the presence of the Vikings in these areas. But the Romans were for sure. A rock found in Gobustan contains a Roman inscription which proves the presence of a centurion of the XII (12th) Roman legion, known as the Fulminat (Lightning) here on the shore of the Caspian Sea during the reign of Emperor Titus Flavius Domitianus in the second half the 1st century AD. Some assume, this may be the easternmost point any Roman patrol even ventured to. I can read the inscription though I am not good in Latin: “IMP DOMITIANO CAESARE AVG GERMANIC LIVIVS MAXIMVS LEG XII FVL” (“Emperor Domitian, the Blessed Caesar Germanicus. Livius Maximus, Legio XII Fulminata”). Near the end of our trip I ask my brother whether he would like to see the “Gobustan kitchen”. He first think I am joking. But I am not. I take him to the place I have read about many times and show him the bowl-shaped depressions carved out in the rock. They were probably used for collecting rainwater, the blood of sacrificed animals or for cooking. I remember from the old people that until quite recently mountain shepherds used these “bowls” for boiling milk by dropping heated stones into them. It may be an explanation about the usage of similar “bowls” by the prehistoric people.

Near the end of our trip I ask my brother whether he would like to see the “Gobustan kitchen”. He first think I am joking. But I am not. I take him to the place I have read about many times and show him the bowl-shaped depressions carved out in the rock. They were probably used for collecting rainwater, the blood of sacrificed animals or for cooking. I remember from the old people that until quite recently mountain shepherds used these “bowls” for boiling milk by dropping heated stones into them. It may be an explanation about the usage of similar “bowls” by the prehistoric people.

The chalky north coast of Normandy captures the heart of every visitor at first sight. Years of seawater erosion and weathering have sculpted the coastline on both the west and east sides of the beach, leaving behind towering white cliffs and protruding headlands pierced by arches of various sizes. No wonder Monet visited Étretat every year between 1883 and 1886 and produced more than 60 paintings.

The chalky north coast of Normandy captures the heart of every visitor at first sight. Years of seawater erosion and weathering have sculpted the coastline on both the west and east sides of the beach, leaving behind towering white cliffs and protruding headlands pierced by arches of various sizes. No wonder Monet visited Étretat every year between 1883 and 1886 and produced more than 60 paintings.

“You are right to envy me. You cannot have any idea how beautiful the sea has been for two days, but what talent it will take to render it, it’s crazy. As for the cliffs, they are like nowhere else. Yesterday, I climbed down to a spot where I had never ventured to go before and saw wonderful things there so I very quickly went back to get my canvases. In the end, I am very happy.”

“You are right to envy me. You cannot have any idea how beautiful the sea has been for two days, but what talent it will take to render it, it’s crazy. As for the cliffs, they are like nowhere else. Yesterday, I climbed down to a spot where I had never ventured to go before and saw wonderful things there so I very quickly went back to get my canvases. In the end, I am very happy.” Following the trail all the way to the top of Manneporte, I could see, on the east side, Porte d’Aval and Pointe d’Aiguille again next to each other as in L’Aiguille et la Porte d’Aval, Étretat. Monet painted the same motif from the beach below us as well. Bathed in the mellow evening light during low tide, the pillar and the arch in the painting hardly appear overwhelming although they still look gigantic compared with the tiny boats between them. While the view before me was imposing, the painting impressed me with its serenity.

Following the trail all the way to the top of Manneporte, I could see, on the east side, Porte d’Aval and Pointe d’Aiguille again next to each other as in L’Aiguille et la Porte d’Aval, Étretat. Monet painted the same motif from the beach below us as well. Bathed in the mellow evening light during low tide, the pillar and the arch in the painting hardly appear overwhelming although they still look gigantic compared with the tiny boats between them. While the view before me was imposing, the painting impressed me with its serenity.

Spinning rides and vendor booths pack the central square. They are selling wooden toys and traditional crafts and that curious gingerbread that seems to be a fixture of the German-speaking festival: heart-shaped with endearments printed in icing, meant to be worn around the neck. There’s music in the streets, and a group has gathered around to watch an old couple who is dancing a slow waltz. I’m surprised to see how many people have arrived wearing the traditional lederhosen and dirndls. As I squeeze my way between hordes of carousing Austrians, I feel as if I have arrived in the wrong city. I hadn’t pictured the town of Mozart’s birth to have such activity.

Spinning rides and vendor booths pack the central square. They are selling wooden toys and traditional crafts and that curious gingerbread that seems to be a fixture of the German-speaking festival: heart-shaped with endearments printed in icing, meant to be worn around the neck. There’s music in the streets, and a group has gathered around to watch an old couple who is dancing a slow waltz. I’m surprised to see how many people have arrived wearing the traditional lederhosen and dirndls. As I squeeze my way between hordes of carousing Austrians, I feel as if I have arrived in the wrong city. I hadn’t pictured the town of Mozart’s birth to have such activity.

The older gentleman sitting across from me tries to engage me in conversation, so I bust out my best German – in my poor imitation of the Northern German accent I had learned in school. I might as well have been speaking gibberish to the Austrian, so we settle on my native tongue. A pair of women join the stilted English conversation, and I finally learn that September 24th is the Feast of St. Rupert, the patron saint of Salzburg. The festival in town occurs on the weekend each year closest to that date.

The older gentleman sitting across from me tries to engage me in conversation, so I bust out my best German – in my poor imitation of the Northern German accent I had learned in school. I might as well have been speaking gibberish to the Austrian, so we settle on my native tongue. A pair of women join the stilted English conversation, and I finally learn that September 24th is the Feast of St. Rupert, the patron saint of Salzburg. The festival in town occurs on the weekend each year closest to that date. But then the three Austrians start a new game that I can only describe as ‘inebriate the foreigner’. A second beer from my new friends is in order, but that isn’t all. I’m obliged to accept a glass of Sturm, a young red wine that tastes amazingly like grape juice. Dangerous for a heavy drinker, but very tasty. A wink from the man and scrunched noses from the women tell me I’m in trouble at their next plot. A girl wearing both a long dirndl dress and a barrel comes by our table. The Austrians hand the girl money, and a single shotglass of clear liquid is placed in front of me. All eyes turn my way and I feel a twinge of foreboding.

But then the three Austrians start a new game that I can only describe as ‘inebriate the foreigner’. A second beer from my new friends is in order, but that isn’t all. I’m obliged to accept a glass of Sturm, a young red wine that tastes amazingly like grape juice. Dangerous for a heavy drinker, but very tasty. A wink from the man and scrunched noses from the women tell me I’m in trouble at their next plot. A girl wearing both a long dirndl dress and a barrel comes by our table. The Austrians hand the girl money, and a single shotglass of clear liquid is placed in front of me. All eyes turn my way and I feel a twinge of foreboding.

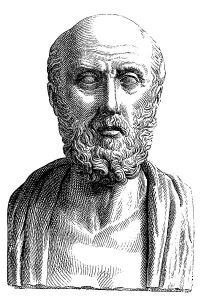

Hippocrates Tree is located in Kos Town. It is said Hippocrates stood under this plane-tree and lectured his medical students. Although it is unlikely that it is the actual tree under which Hippocrates stood, a far more plausible explanation is that the current tree is a descendant of the one under which Hippocrates lectured. Many health establishments around the world have taken cuttings from this tree and planted them in their own grounds. Hippocrates tree is easy to distinguish as it is supported by a large metal framework. I could not help but feel impressed that a man to whom medicine owes so much might have once stood in this same spot.

Hippocrates Tree is located in Kos Town. It is said Hippocrates stood under this plane-tree and lectured his medical students. Although it is unlikely that it is the actual tree under which Hippocrates stood, a far more plausible explanation is that the current tree is a descendant of the one under which Hippocrates lectured. Many health establishments around the world have taken cuttings from this tree and planted them in their own grounds. Hippocrates tree is easy to distinguish as it is supported by a large metal framework. I could not help but feel impressed that a man to whom medicine owes so much might have once stood in this same spot.

The sick would visit the Asklepion which was staffed by several therapists, priests and later doctors. The patient stayed for a few days and might take part in massage, gymnastics, bathing and follow a special diet.

The sick would visit the Asklepion which was staffed by several therapists, priests and later doctors. The patient stayed for a few days and might take part in massage, gymnastics, bathing and follow a special diet. As you approach the Asklepion it opens out in front of you and you can clearly see the three levels that make it up. Naturally, the main temple to Asklepios is at the top. I made my way slowly to the top, partly due to the heat but also so as not to miss anything on the way. My guidebook informed me that the lower levels were once accommodation and that the second terrace contained smaller temples, including one to Apollo. The authentic columns, arches and stone steps still look impressive and make you wonder about the people who used the Asklepios as a centre of healing all those years ago.

As you approach the Asklepion it opens out in front of you and you can clearly see the three levels that make it up. Naturally, the main temple to Asklepios is at the top. I made my way slowly to the top, partly due to the heat but also so as not to miss anything on the way. My guidebook informed me that the lower levels were once accommodation and that the second terrace contained smaller temples, including one to Apollo. The authentic columns, arches and stone steps still look impressive and make you wonder about the people who used the Asklepios as a centre of healing all those years ago.